The Storyline

"Real families.Real discoveries.Real stories."

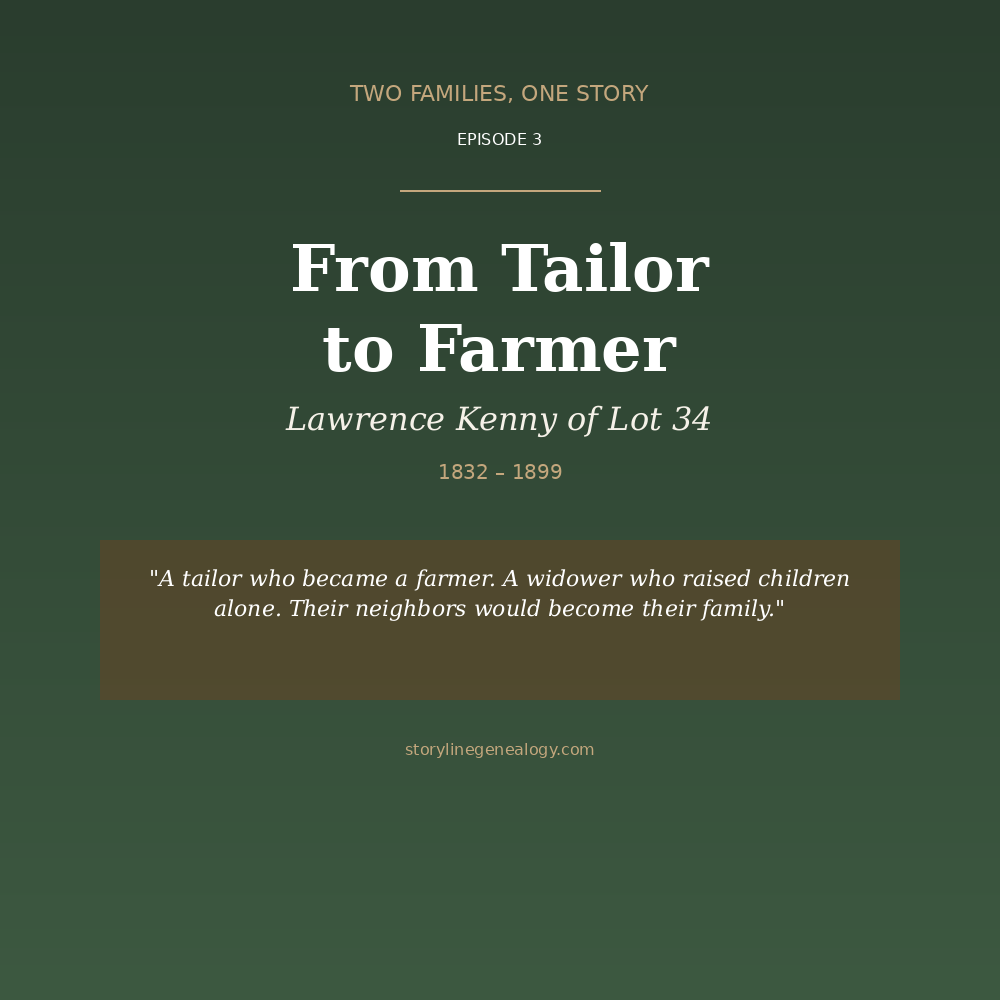

Two Families, One Story: From Tailor to Farmer

In October 1832, Lawrence Kenny brought his infant son James to St. Patrick's Church in St. John's, Newfoundland. Within three years, the family would leave the fishing settlement behind for the farmland of Prince Edward Island. The 1841 census captures Lawrence at a pivot point: still listed as "Tailor," the trade he brought from Ireland. By the next census, that occupation would be gone. Lawrence Kenny, tailor, would become Lawrence Kenny, farmer—and his children would marry into the Connors family three times over.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

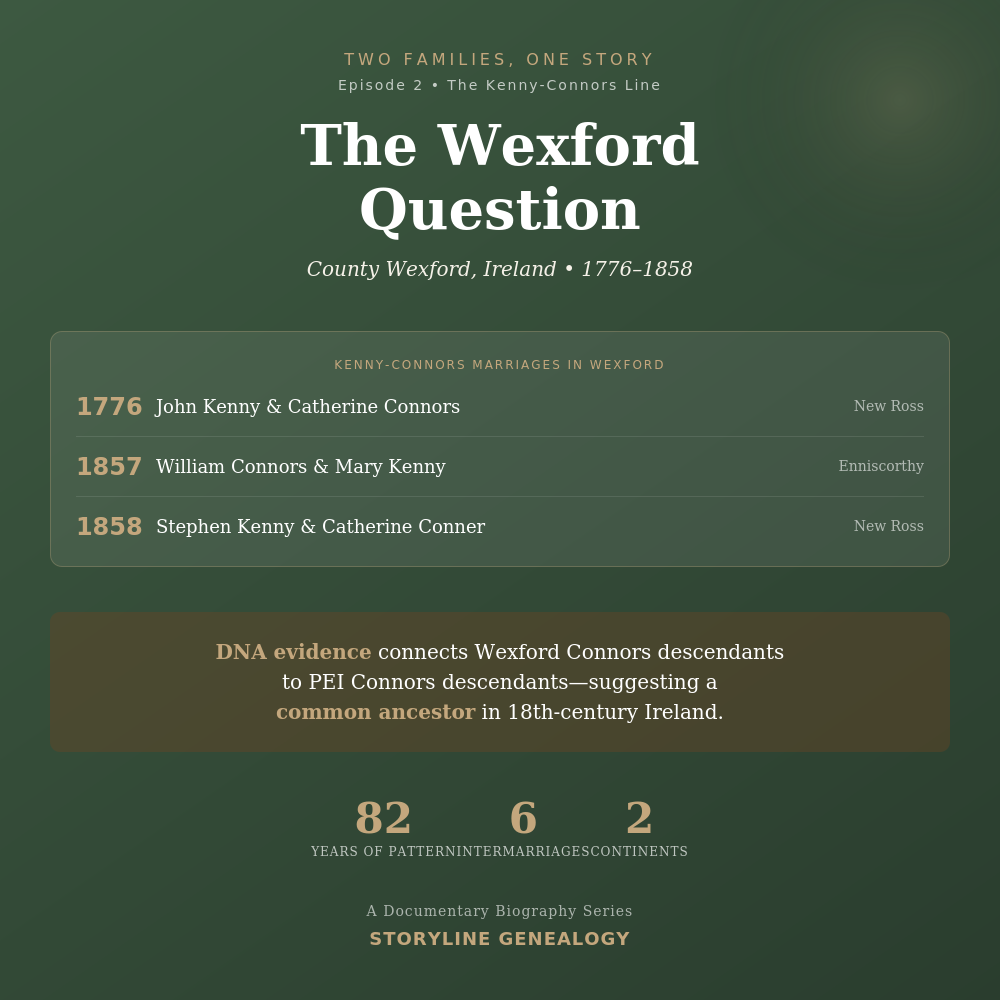

Two Families, One Story: The Wexford Question

In 1776—the same year the American colonies declared independence—John Kenny married Catherine Connors in New Ross, County Wexford. Eighty-two years and three more Kenny-Connors marriages later, were the families who intermarried on Prince Edward Island continuing a pattern that stretched back to Revolutionary-era Ireland?

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

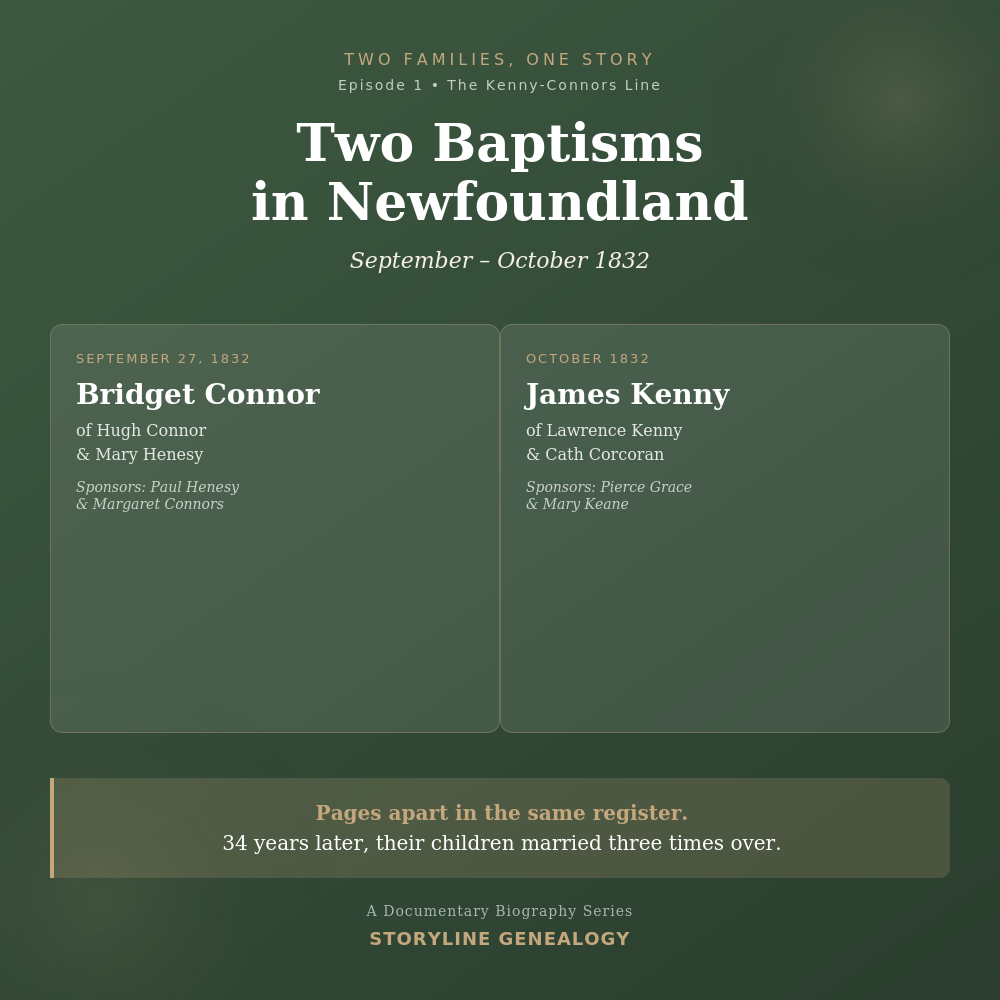

Two Families, One Story: Two Baptisms in Newfoundland

In autumn 1832, two Irish families—part of the same fishing community in St. John's, Newfoundland—each brought a child to be baptized. Their entries appear on consecutive pages of the same parish register. Neither family knew the significance of the other's presence. Thirty-four years later, their descendants would meet on Prince Edward Island and marry three times over.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

Spools of Thread: On Holding Things Together, Imperfectly

Nine for dinner at my parents' rock maple table—both leaves extended, held in place with spools of thread. My mother's "company's coming" dishes. Her silverware. Her artificial flowers. The mechanism has been broken for years, but we make do. We hold things together imperfectly.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: From Research to Story

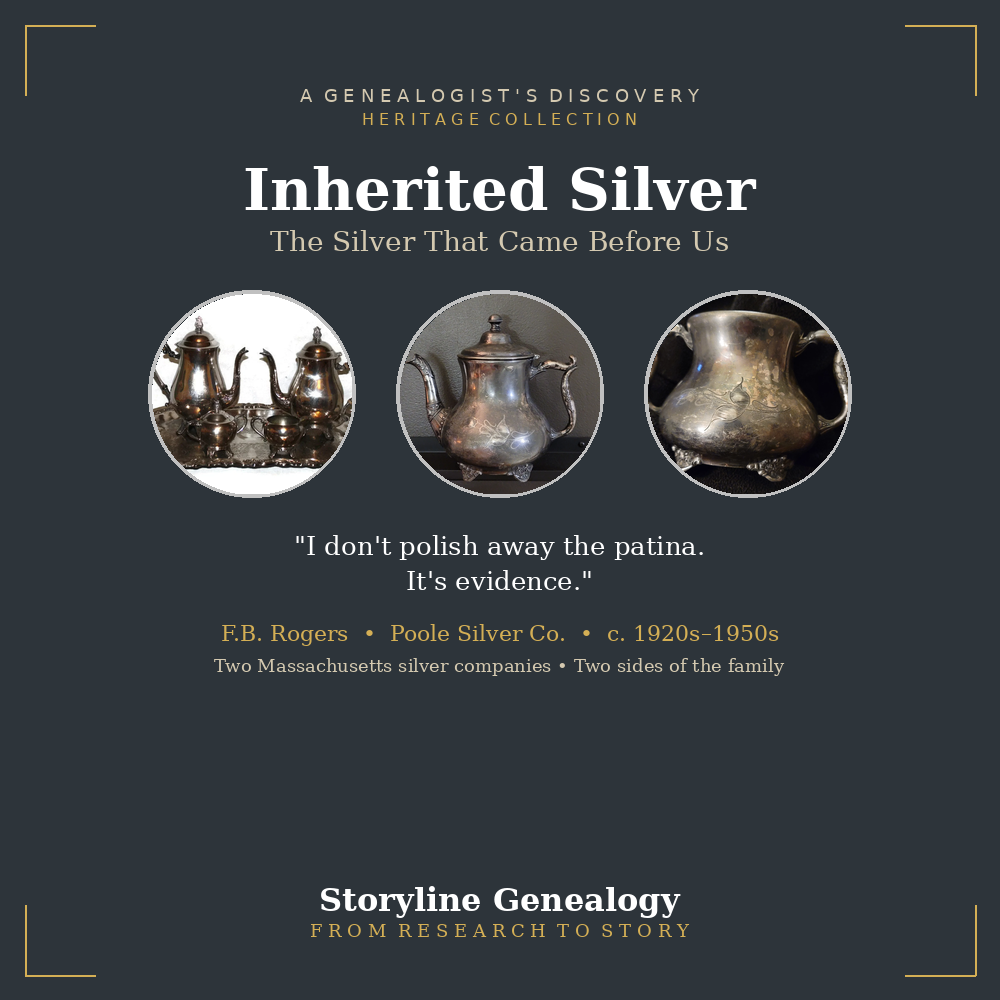

The Silver That Came Before Us: Inherited Silver Tea Sets

Two silver tea sets sit in my home—one from my mother's house, one a gift from her when I set up my first home. As a genealogist, I examine maker's marks, research company histories, and narrow the timeline to discover which ancestors might have owned these pieces.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: From Research to Story.

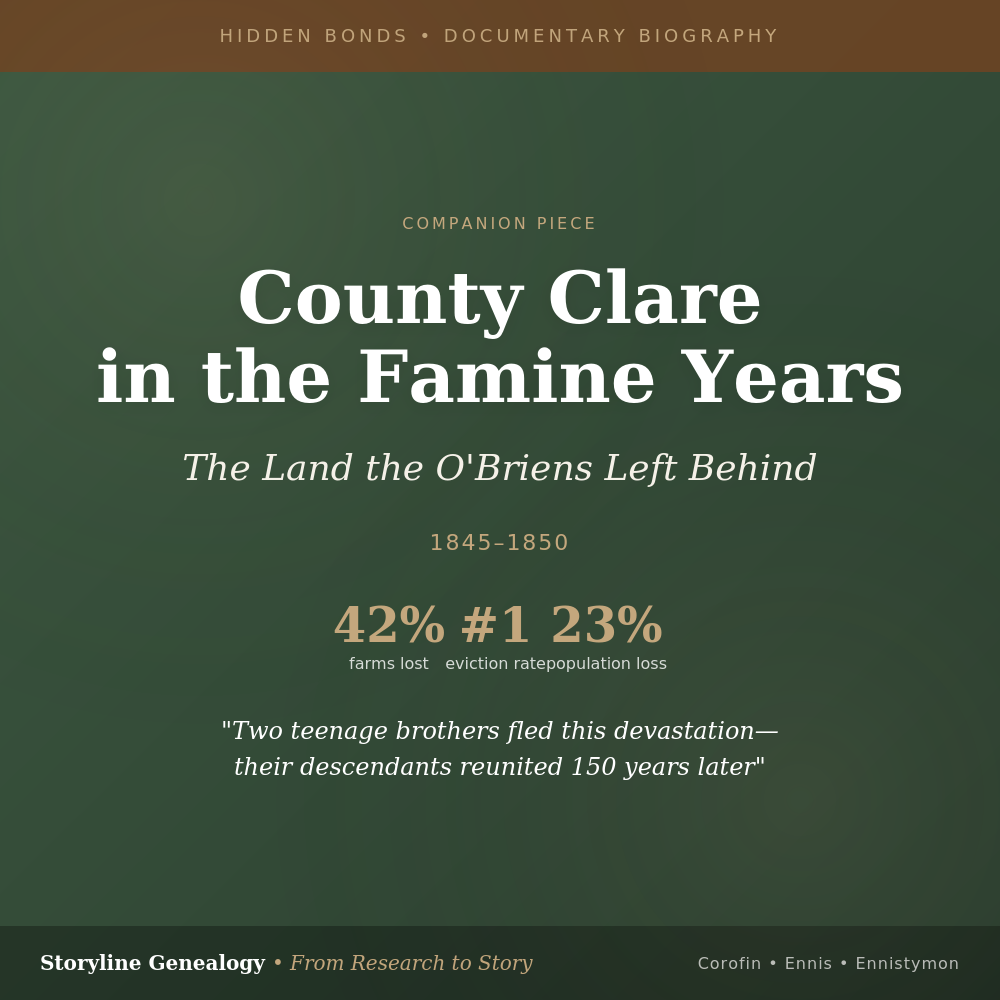

County Clare in the Famine Years: Hidden Bonds Companion Piece

County Clare lost 42% of its farms. It had the highest eviction rate in Ireland. The Ennistymon workhouse saw nearly 5,000 deaths. This is the land Patrick and Terrence O'Brien fled in the late 1840s—the land where their family name once meant royalty, reduced to devastation. This companion piece to the Hidden Bonds documentary series explores what two teenage brothers witnessed before they embarked for America, never to see each other again.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

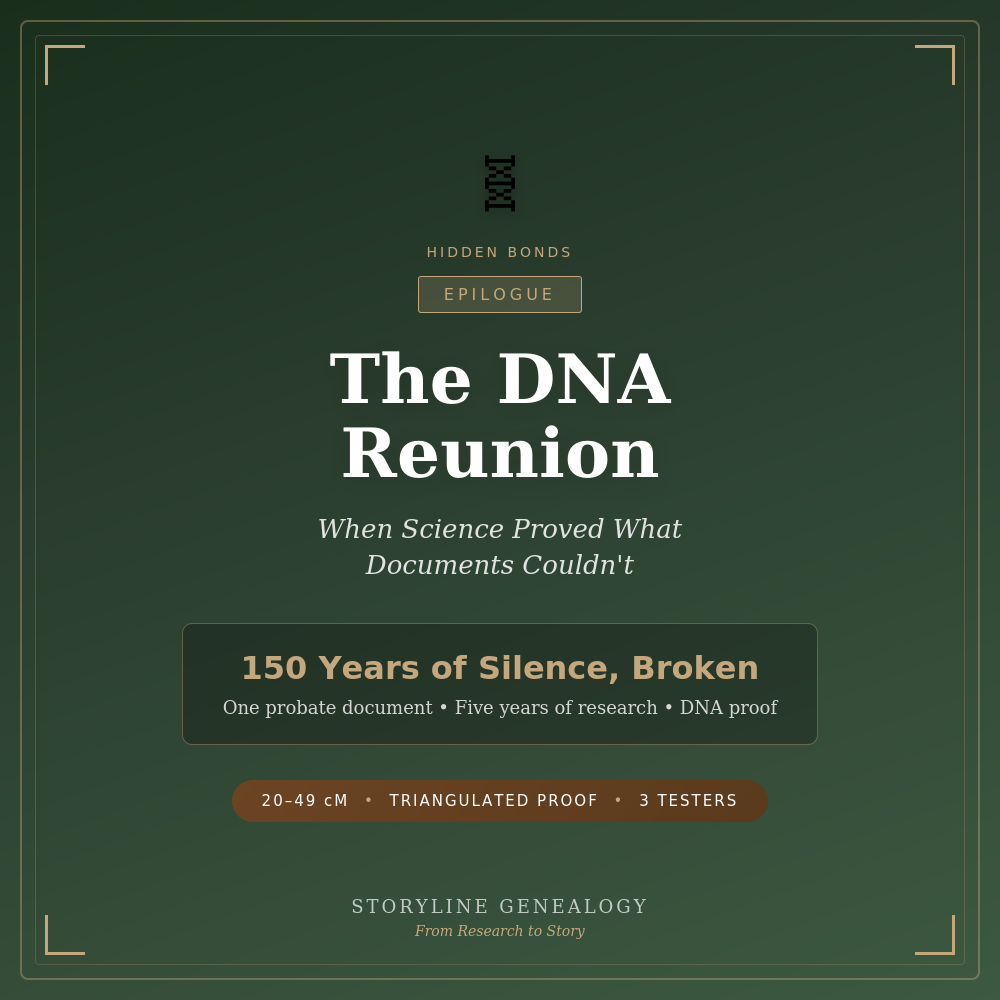

Hidden Bonds Epilogue: The DNA Reunion

When Terrence O'Brien died in 1874, a single line in the probate document mentioned "Uncle Patrick O'Brien in Newport, Kentucky." For 150 years, that reference stood alone—no other evidence connected the New York and Kentucky families. Then DNA testing proved what documents couldn't.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

Hidden Bonds Prologue: The Blood of Kings

They were descended from the High King who united Ireland. For three centuries, the Penal Laws tried to erase them. Then DNA proved what history couldn't destroy—a thousand years of royal blood connecting two Famine refugees to Brian Boru himself.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

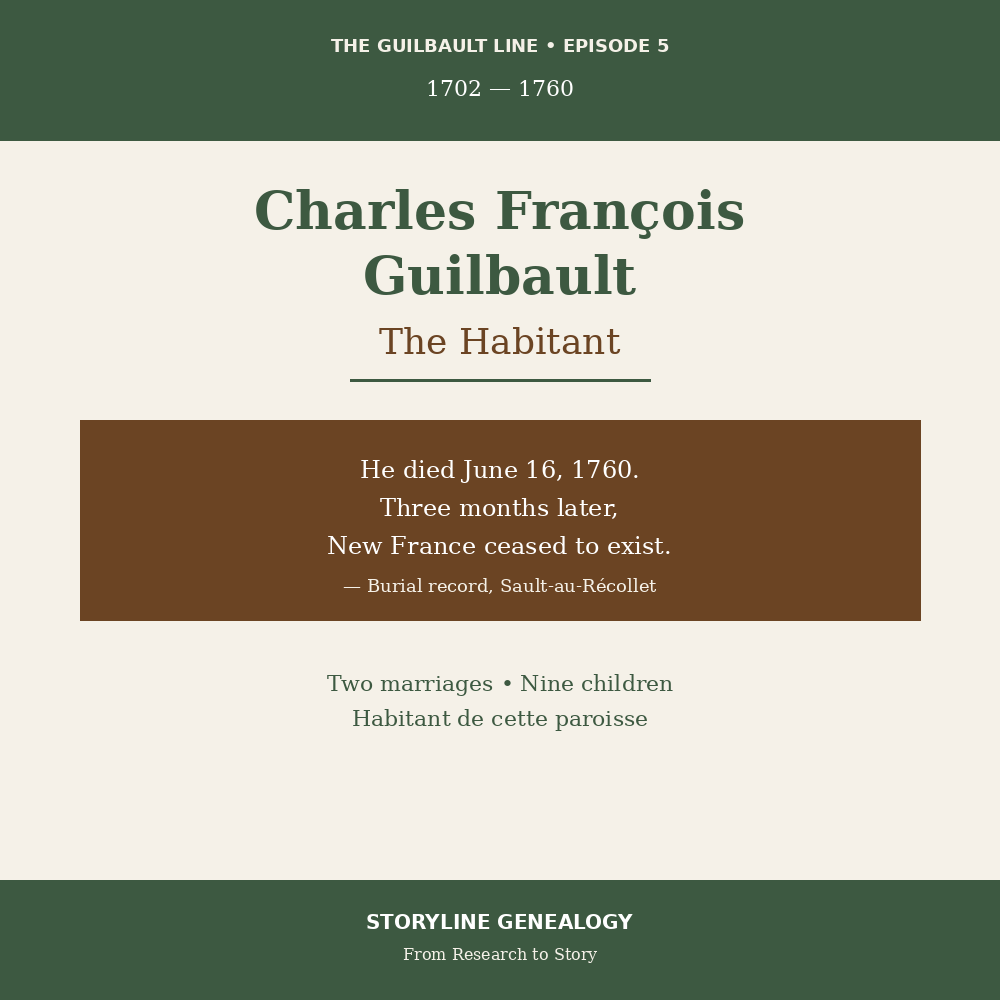

The Guilbault Line: Charles Francois Guilbault

Charles François Guilbault died on June 16, 1760. Three months later, Montreal would surrender and New France would cease to exist. The priest who buried him at Sault-au-Récollet recorded a single word for his life's work: habitant. It was enough. His grandson would become a voyageur who married an Ojibwe woman—but first, there was this: a farmer who lived his entire fifty-seven years under the fleur-de-lys and died as the colony collapsed around him.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

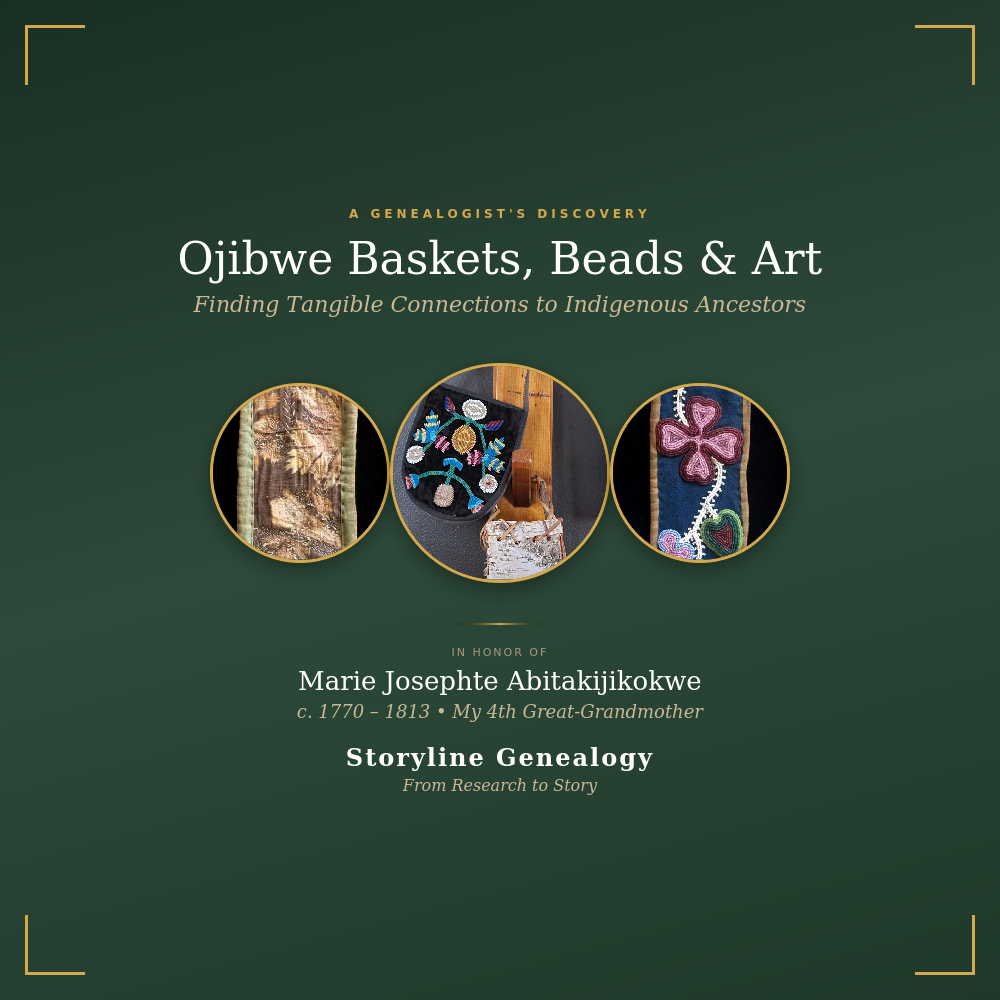

Ojibwe Baskets, Beads, and Art

When I discovered my Ojibwe 4th great-grandmother, Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe, I wasn't prepared for how profoundly that discovery would change the way I understood my family's history. For generations, she had existed only as a shadow in the records—"Sauvagesse," a generic French term meaning "Indigenous woman." No name. No story. No identity.

Then, in a marriage record from 1801, a priest had written her full Ojibwe name: Abitakijikokwe. After 200 years of silence, she emerged from the records with her Indigenous identity intact.

And so began my journey into the world of Ojibwe art—searching for tangible connections to the woman who founded my Métis family line.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies — From Research to Story

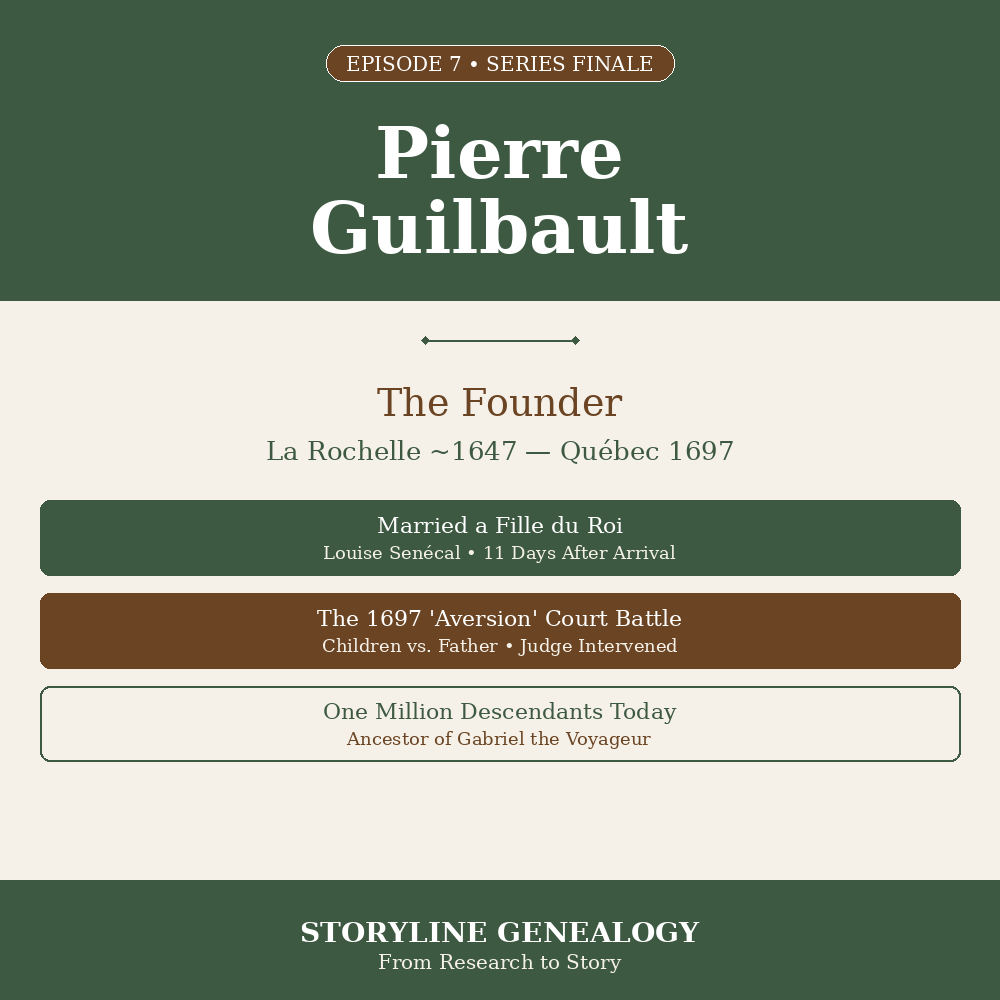

The Guilbault Line: Pierre Guilbault

Every family line has a beginning. For the Guilbaults of New France—whose descendants would include master masons, Quebec patriots, voyageurs who married into Ojibwe families, and eventually a million people living today—that beginning was Pierre Guilbault, a young man from La Rochelle who crossed the Atlantic in 1657. He failed twice to marry before wedding Fille du Roi Louise Senécal just eleven days after her arrival. They built a prosperous farm, survived a marital separation, and raised four children. But when Louise died in 1693, Pierre's attempt to remarry the same day triggered a family war so bitter that the judge used the word "aversion" to describe their mutual hatred.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

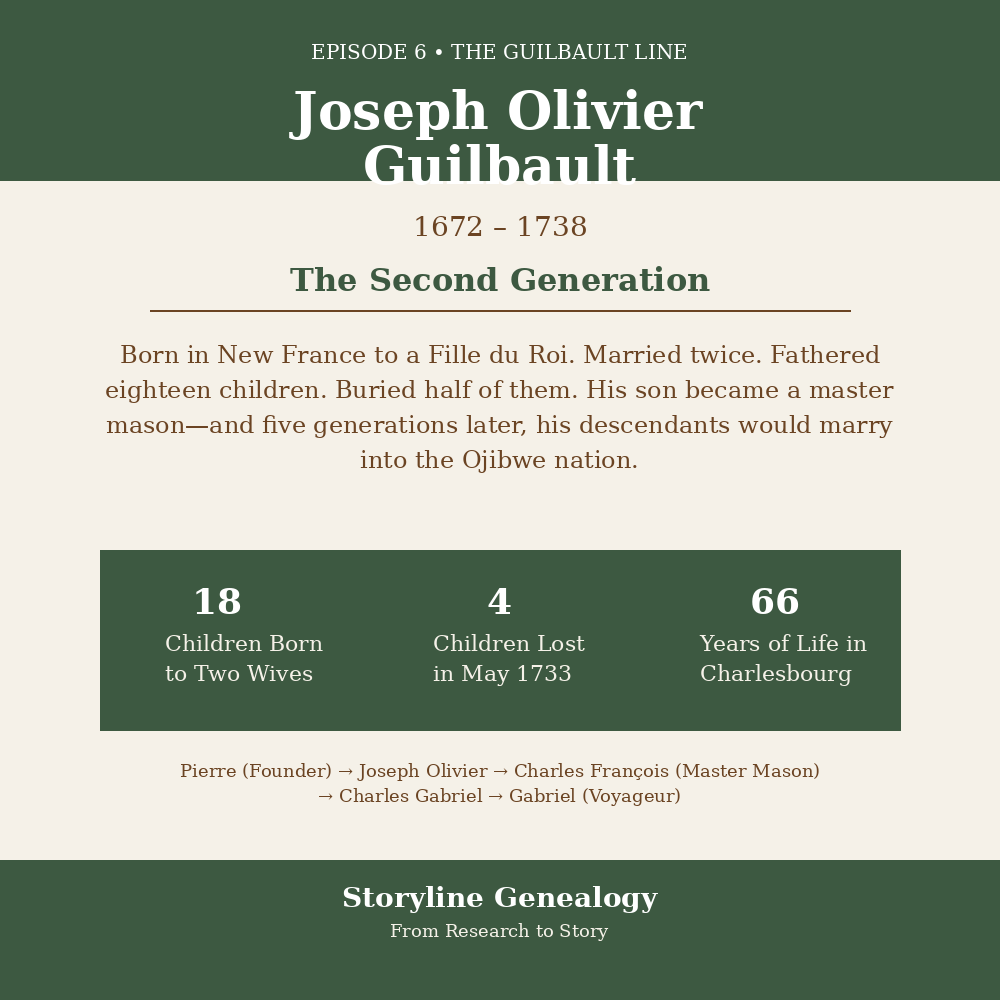

The Guilbault Line: Joseph Olivier Guilbault

He was born just five years after his parents' wedding—the first son, baptized in the parish church of Notre-Dame-de-Québec in March 1672. His father Pierre had arrived from La Rochelle fifteen years earlier; his mother Louise Senécal was a Fille du Roi who crossed the Atlantic to build a new life in New France. Joseph Olivier Guilbault would never know that ocean crossing. He was the second generation—born in the colony, rooted in the soil of Charlesbourg. He would marry twice, father eighteen children, bury too many of them, and live to see his son become an established habitant.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

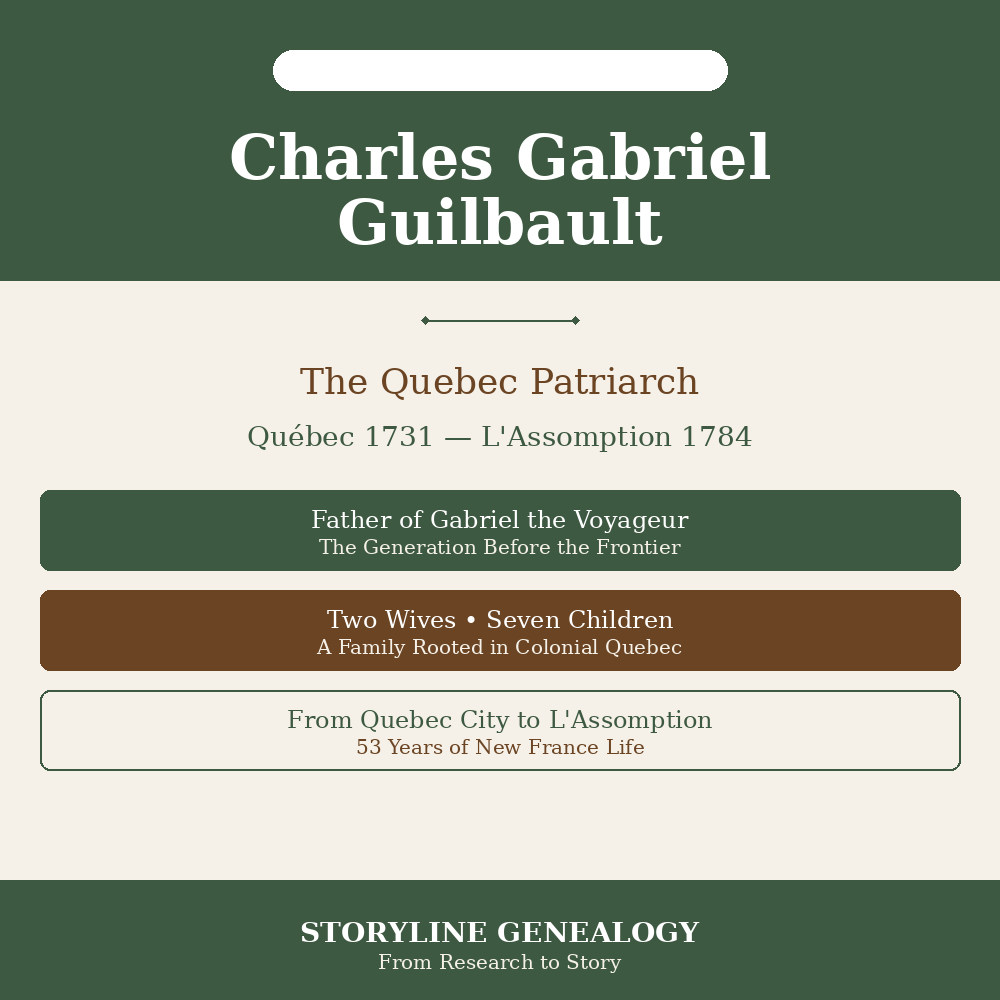

The Guilbault Line: Charles Gabriel Guilbault

Before Gabriel Guilbault paddled canoes into the pays d'en haut and married an Ojibwe woman, there was his father—another Gabriel, born Charles Gabriel Guilbault in Quebec City in 1731. This Quebec patriarch married twice, raised four sons to adulthood, and established the family in L'Assomption that would eventually bridge French and Indigenous worlds. His 53-year life span encompassed the British Conquest and the transformation of New France, setting the stage for his son's frontier adventures.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

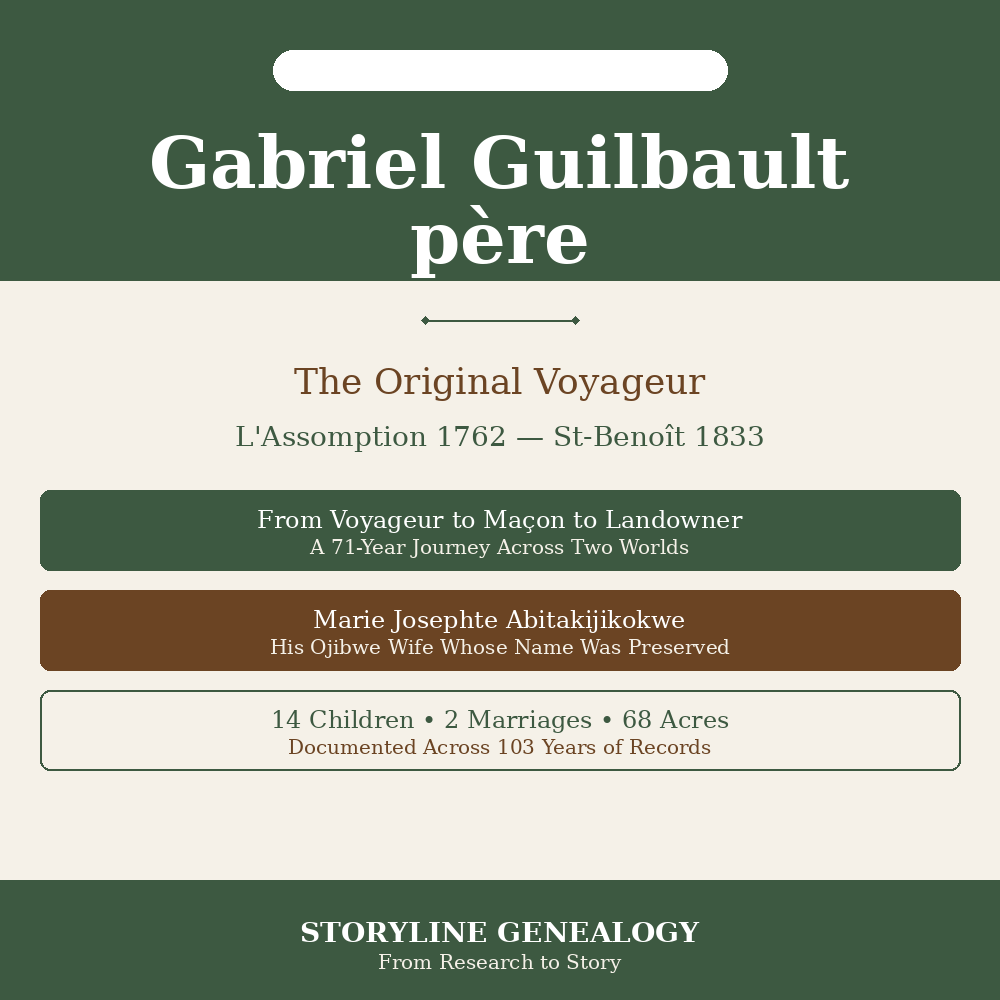

The Guilbault Line: Gabriel Guilbault pere

Gabriel Guilbault was born into the rhythms of New France and lived to see that world transform. A voyageur who paddled canoes to Lake Superior, he married an Ojibwe woman whose name—Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe—would be preserved in parish records for over a century. His 71-year journey from L'Assomption to St-Benoît, from paddler to mason to landowner, left behind something extraordinary: documented proof of Métis heritage for generations of descendants.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

Finding Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe

For generations, she existed only as "Sauvagesse"—the nameless Indigenous wife of a French-Canadian voyageur. Like thousands of Indigenous women erased from colonial records, Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe seemed destined to remain forever unknown.

But in 2024, using FamilySearch's new Full Text Search feature and systematic research across five Quebec parishes, her full Ojibwe name emerged from a 1801 marriage record. Across 15 documents spanning nearly a century, Marie Josephte transformed from "unknown Indigenous woman" to one of the best-documented Indigenous ancestors in Quebec parish records.

This discovery proves your "nameless" ancestors may be findable—if you know where and how to look.

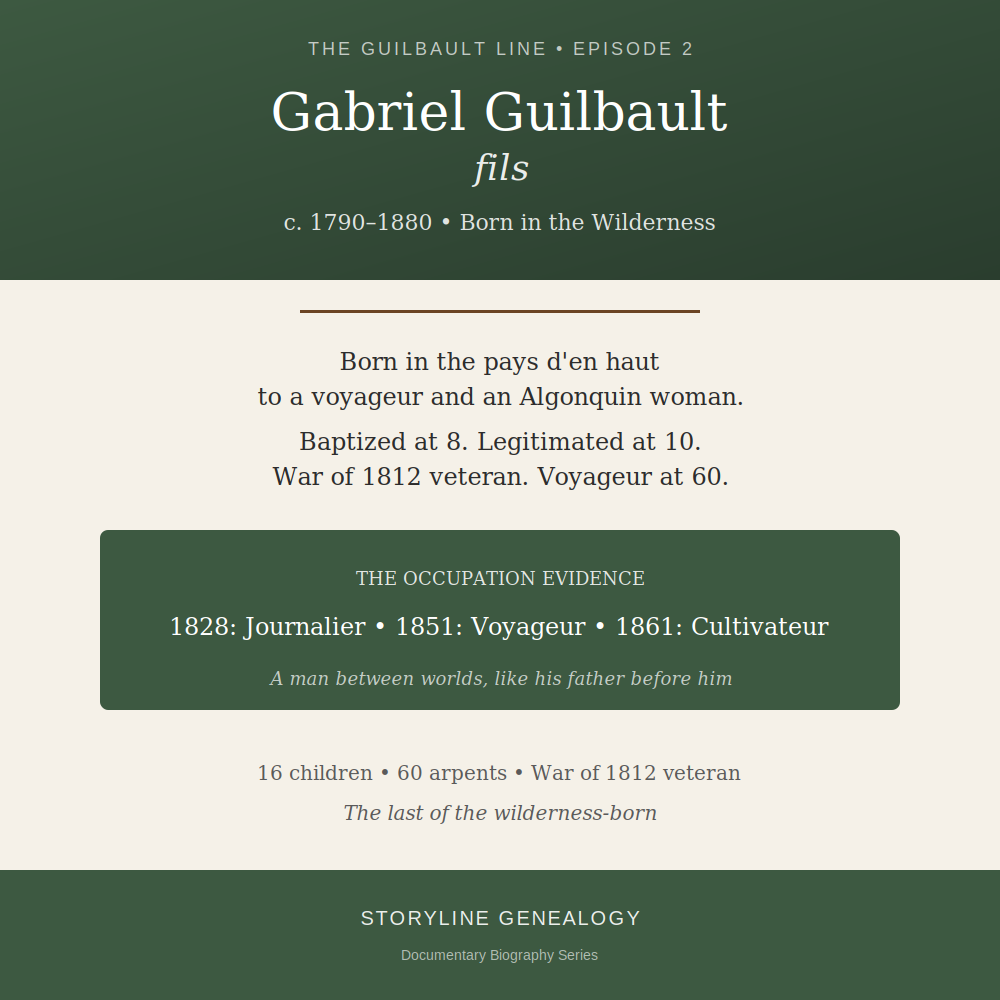

The Guilbault Line: Gabriel Guilbault fils

Gabriel Guilbault fils was born around 1790 in the pays d'en haut—the vast interior wilderness of the fur trade—to a French-Canadian voyageur and an Algonquin woman named Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe. Conditionally baptized at age eight when his family returned to the St. Lawrence Valley, legitimated at ten when his parents formally married, Gabriel lived a life between worlds. The records show his occupation shifting from journalier to voyageur to cultivateur—still claiming the paddle at sixty years old. Father of sixteen children, owner of sixty arpents, he died in 1880 as the last of the wilderness-born.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy Documentary Biography series: Following one family line through the documents that prove it—birth to death, generation to generation.

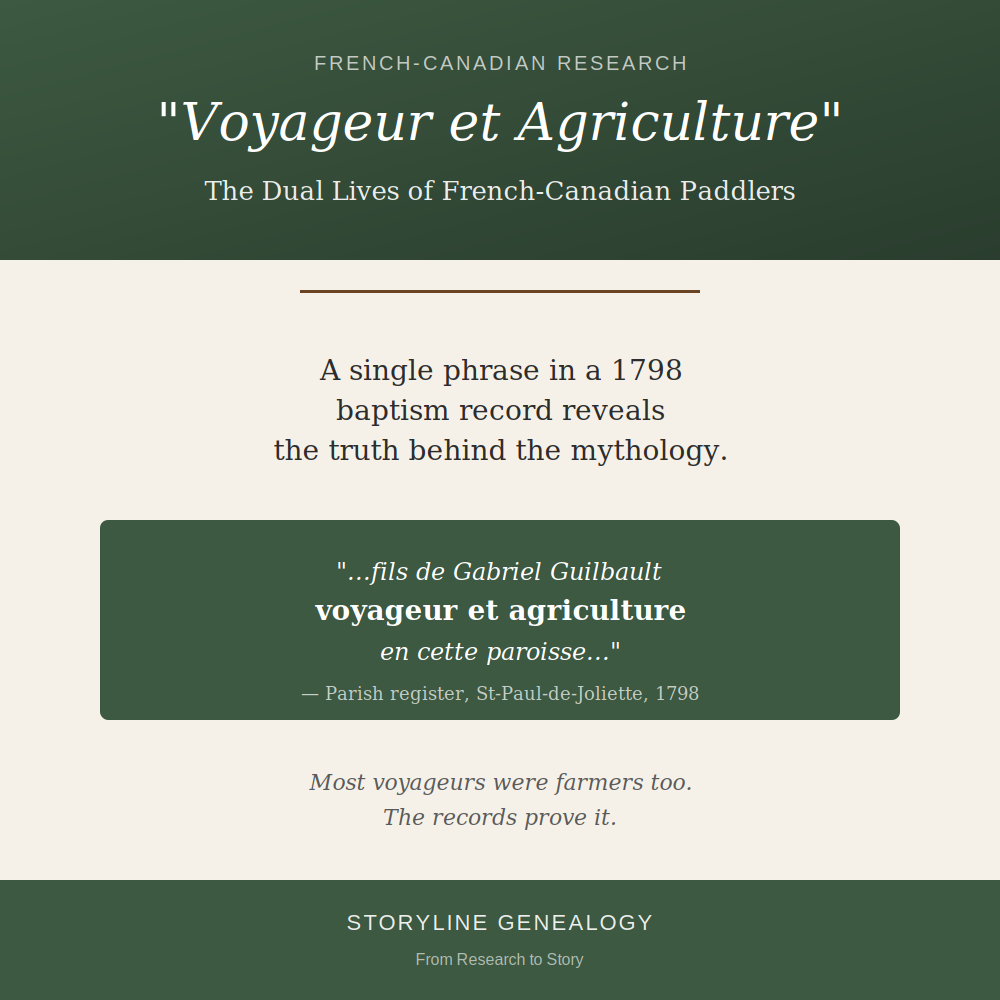

“Voyageur et Agriculture”: The Dual Lives of French-Canadian Paddlers

A single phrase in a 1798 baptism record—"voyageur et agriculture"—reveals what the romantic mythology often obscures: most voyageurs were seasonal workers who returned to their farms each autumn. They weren't footloose adventurers who abandoned civilization. They were habitants who paddled. This post explores the rise and fall of the fur trade, the economics of the canoe brigades, and what the primary sources actually say about these men who lived between two worlds.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy French-Canadian Research series: Understanding the records, the context, and the lives they document.

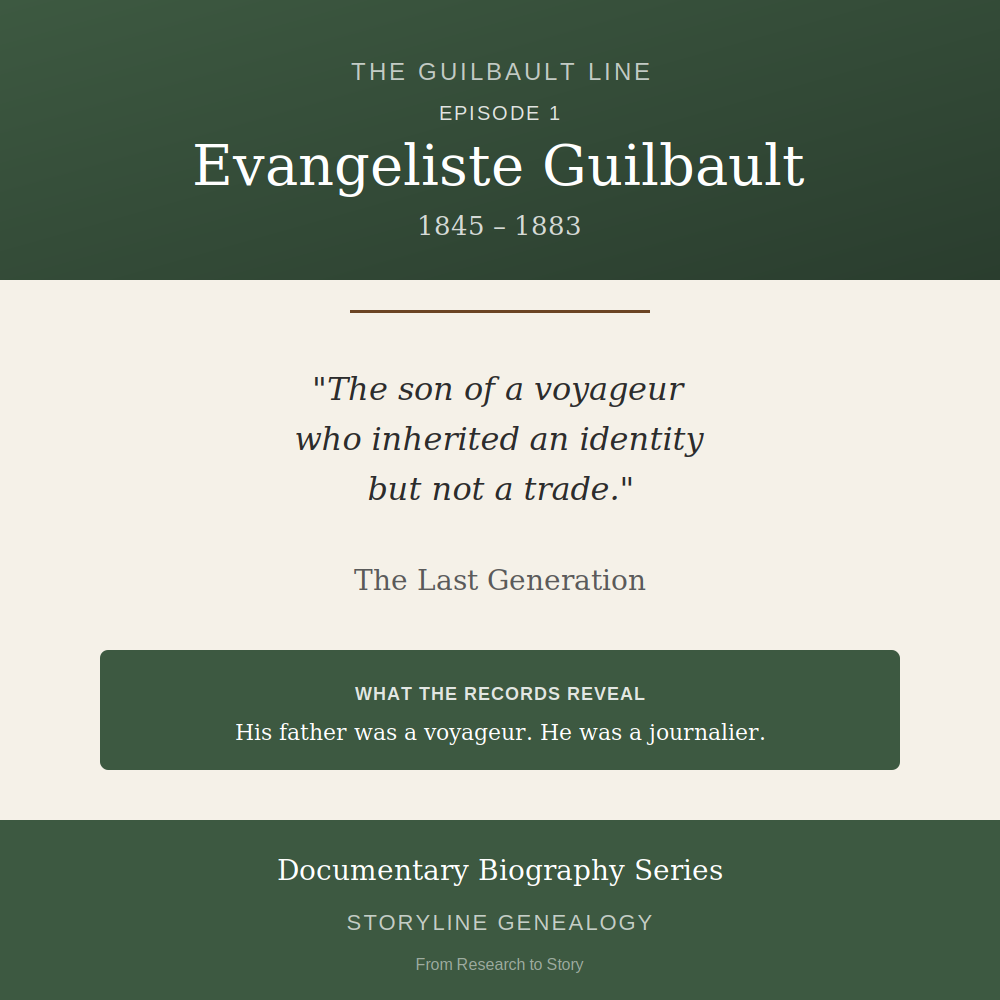

The Guilbault Line: Evangeliste Guilbault

His father was a voyageur. He was a journalier. The primary sources tell a story that family narratives overlooked—of a man caught between eras, who died at 38 leaving three children under four and a widow who would live to ninety-one. This is not the story of a voyageur. This is the story of the last generation.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

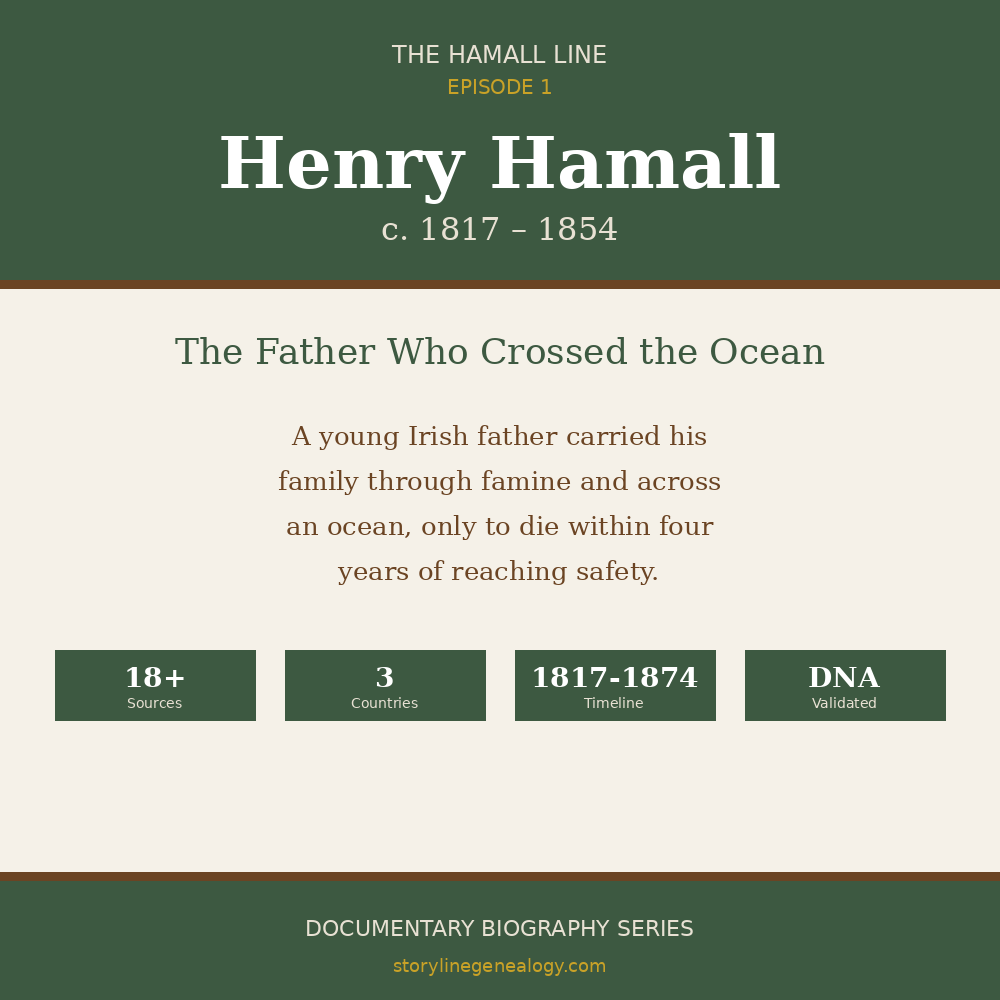

The Hamall Line: Henry Hamall

Born around 1817 in County Monaghan, Ireland, Henry Hamall carried his family through famine and across an ocean, only to die within four years of reaching safety. This documentary biography traces his 1841 marriage to Mary McMahon, their emigration during the Great Famine, and the blended family that would eventually solve a seven-year genealogical mystery.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story

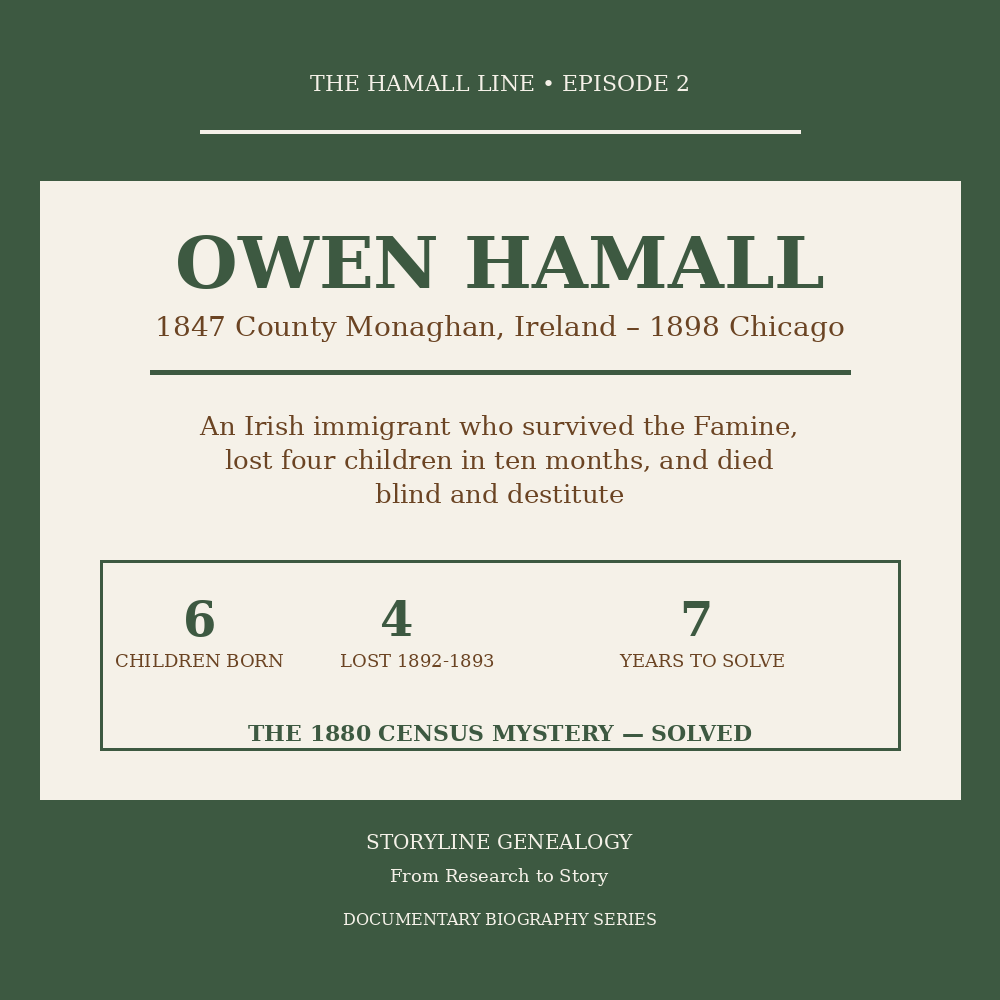

The Hamall Line: Owen Hamall

Owen Hamall was born in 1847 in County Monaghan, Ireland—the year the Great Famine reached its devastating peak. He survived the emigration to Montreal, his father's early death, and his mother's remarriage that created a blended family. In Chicago, he built a life as an iron molder, married Kate Griffith, and had six children. Then tragedy struck: four children died within ten months. Owen went blind, appeared on Chicago's "Destitute List," and died at 51. A mysterious census entry—"Hammil, Thornton"—took seven years to solve, finally revealing the half-brother hidden in plain sight since 1880.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Documentary Biographies From Research to Story