The Guilbault Line: Gabriel Guilbault fils

Gabriel Guilbault fils

Sometime around June 1790, a child was born in the pays d'en haut—the vast interior wilderness stretching from the Great Lakes to the prairies. His father was Gabriel Guilbault, a French-Canadian voyageur paddling the canoe brigades of the fur trade. His mother was Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe, an Algonquin woman whose name meant "Caribou Woman" in her own language. The boy would be named Gabriel, like his father. But unlike most children born to the habitants of the St. Lawrence Valley, he would not see the inside of a church for eight years.

In October 1798, the family returned to civilization. At the parish church of St-Paul-de-Joliette, a priest performed a conditional baptism for the eight-year-old boy—acknowledging that he had likely been baptized informally by a missionary in the wilderness, but completing the sacrament with proper ceremony now that he was within reach of the church. The record describes his father as "voyageur et agriculture"—paddler and farmer, a man living between two worlds.

Three years later, in January 1801, Gabriel's parents finally formalized their union in the eyes of the church. The marriage record at Oka documents not only their wedding but the legitimation of four children born before it: Gabriel, age ten and a half; Angélique, age eight; Joseph, age four; and François, age seventeen months. With a stroke of the priest's pen, these wilderness-born children became legitimate in the eyes of both church and state.

Vital Records Summary

The Legitimation

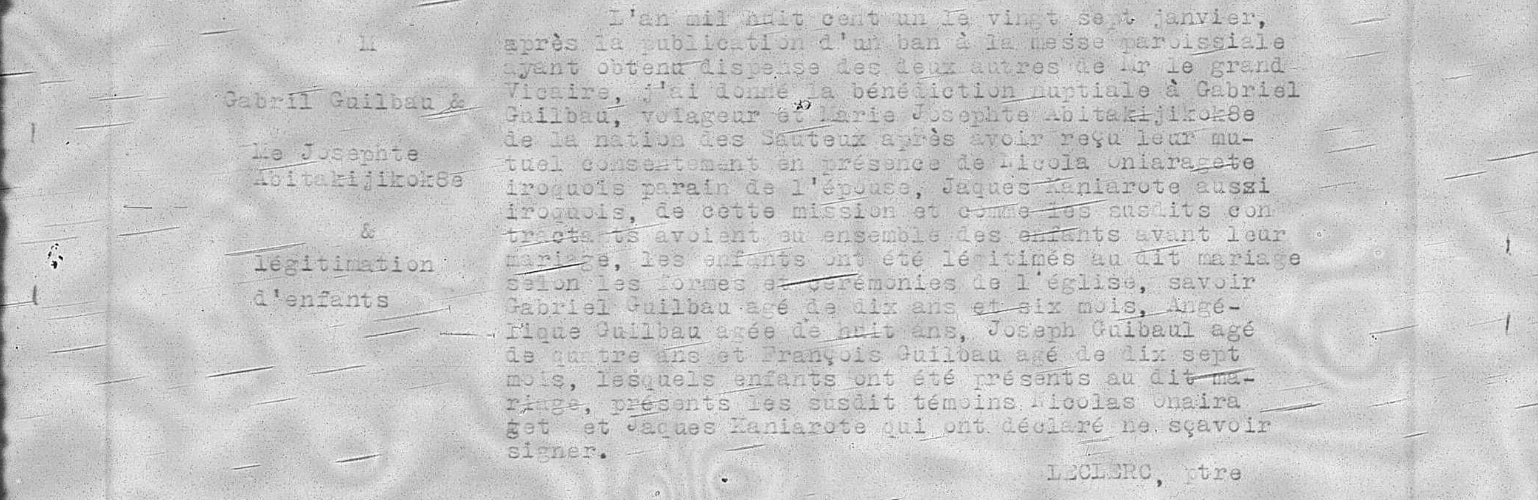

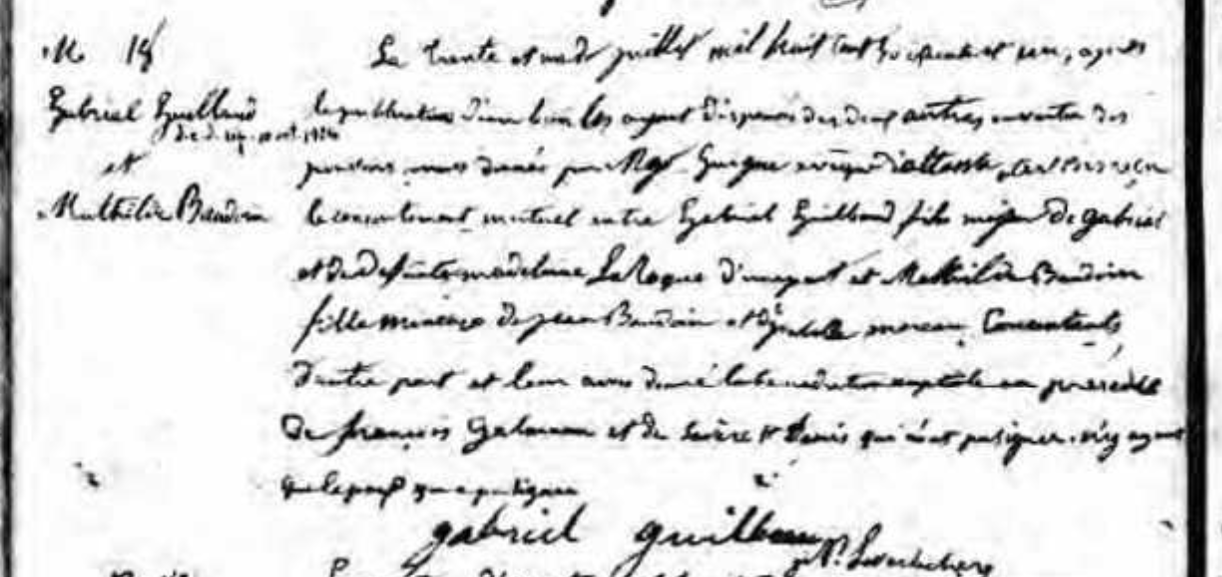

The 1801 marriage record at Oka is one of the most remarkable documents in the Guilbault family archive. It records the formal church wedding of Gabriel Guilbault, voyageur, to Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe, "de la nation des Sauteux"—of the Saulteaux (Ojibwe) nation. But it does far more than document a marriage. It legitimates a family.

From the Marriage Record, 27 January 1801

For Gabriel fils, now ten and a half years old, this ceremony transformed his legal status. Born in the wilderness to unmarried parents, he had been—in the eyes of the church—illegitimate. The legitimation changed that. He was now a recognized son, with full rights of inheritance and standing in colonial society. Whatever his parents' life had been in the pays d'en haut, whatever customs they had followed there, the church had now blessed their union and their children.

The witnesses to this ceremony were Indigenous men: Nicolas Onaragete, Iroquois, godfather of the bride, and Jaques Kaniarote, also Iroquois. This was not a marriage that erased Marie Josephte's identity or community—it was witnessed by her people, in a mission church that served Indigenous Catholics.

A Life Between Worlds

Gabriel fils grew up straddling two identities. His father was a voyageur who also farmed. His mother was an Algonquin woman who had married into French-Canadian society. And Gabriel himself would spend his long life moving between the same worlds—sometimes a farmer, sometimes a day laborer, and even in his sixties, still a voyageur.

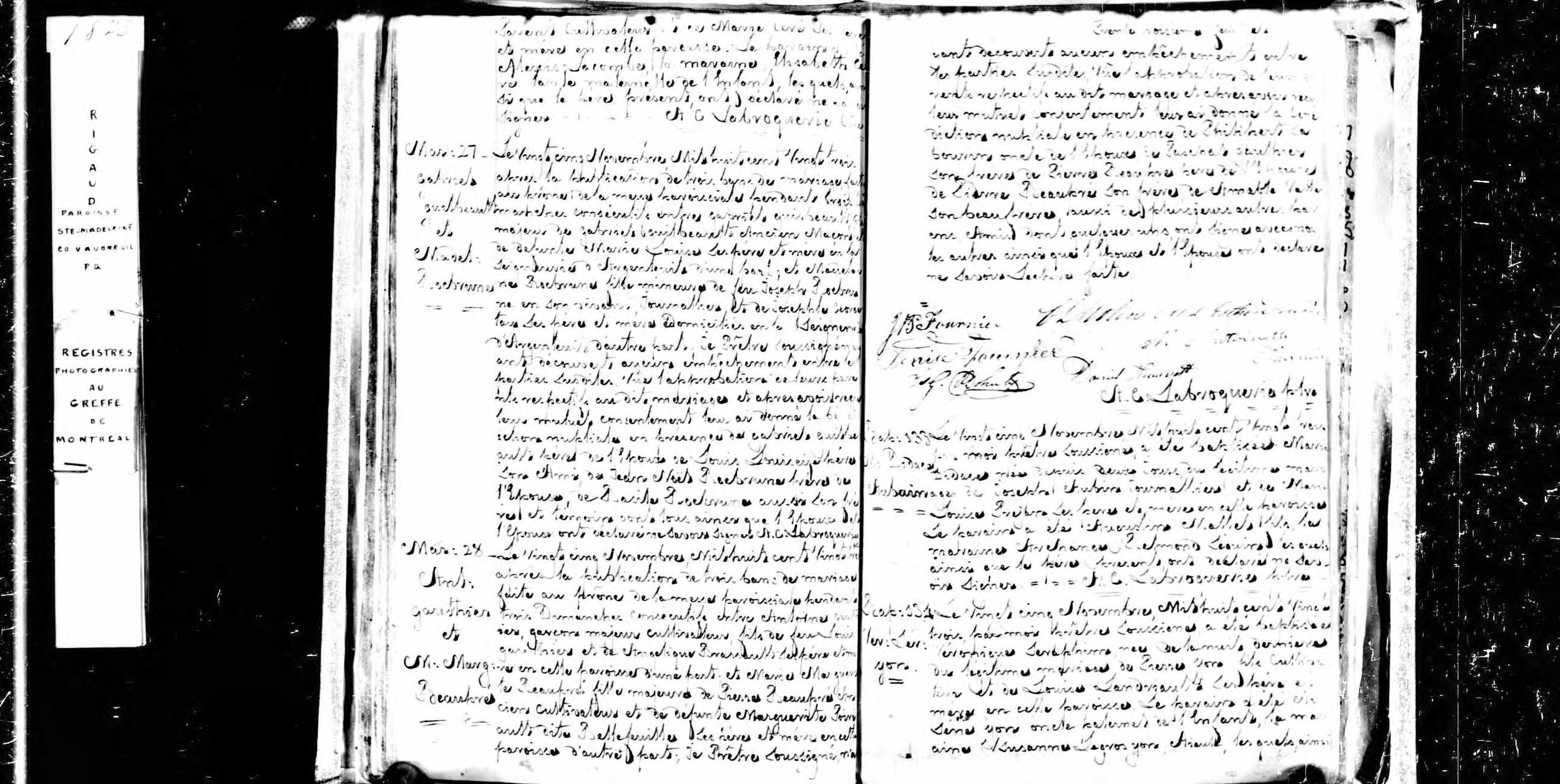

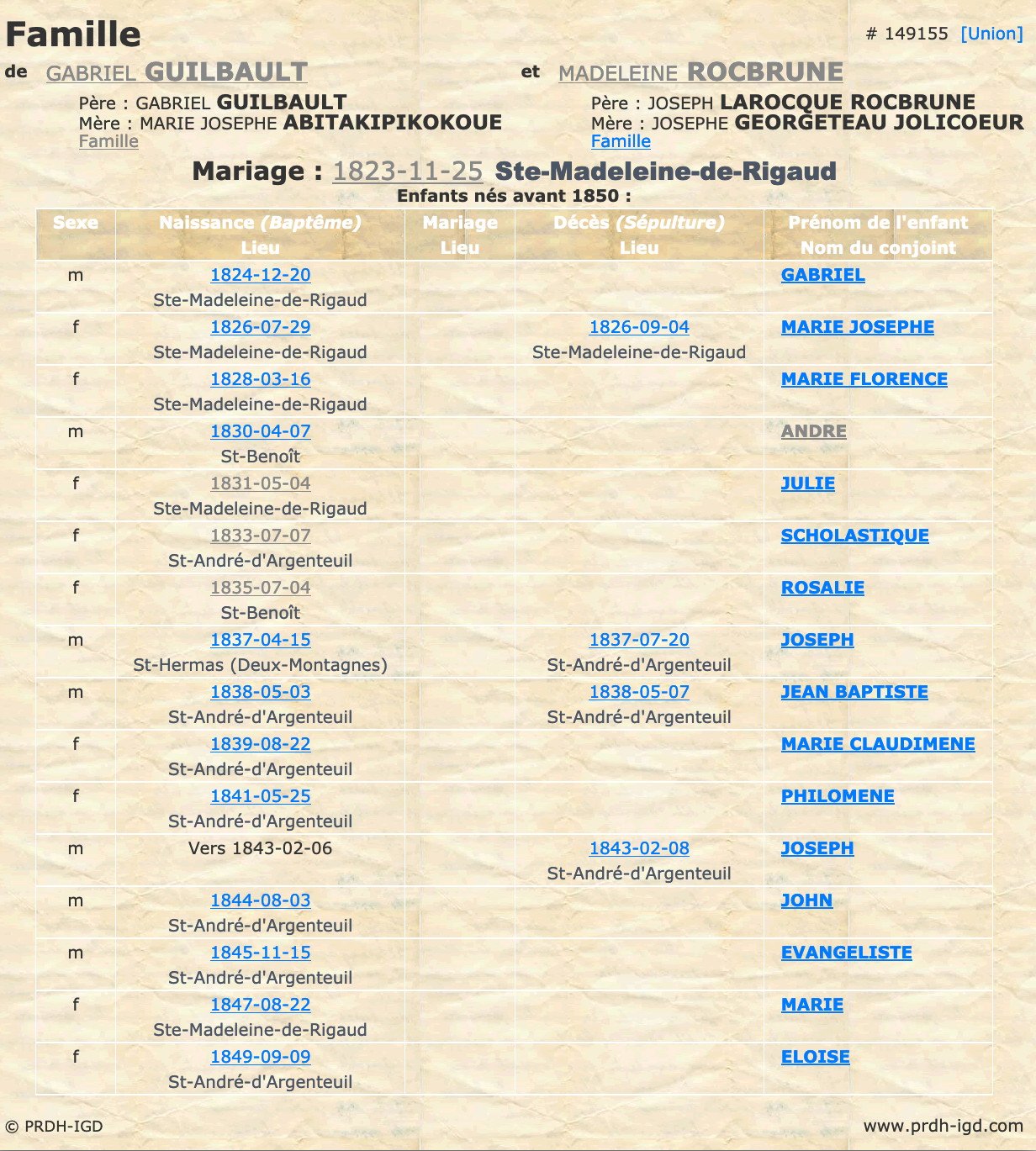

In 1823, at approximately thirty-three years of age, Gabriel married Madeleine Rocbrune (also spelled Larocque) at Ste-Madeleine-de-Rigaud. Her parents were Joseph Larocque Rocbrune and Josephe Georgeteau Jolicoeur—a solidly French-Canadian family with no apparent Indigenous connections. Gabriel was marrying into the settled habitant class, planting his own roots in the St. Lawrence Valley.

Over the next quarter century, Gabriel and Madeleine would have at least sixteen children. The baptisms scattered across multiple parishes—Ste-Madeleine-de-Rigaud, St-Benoît, St-André-d'Argenteuil, St-Hermas—suggest a family that moved frequently, following work and opportunity across the region northwest of Montreal.

The Occupation Evidence

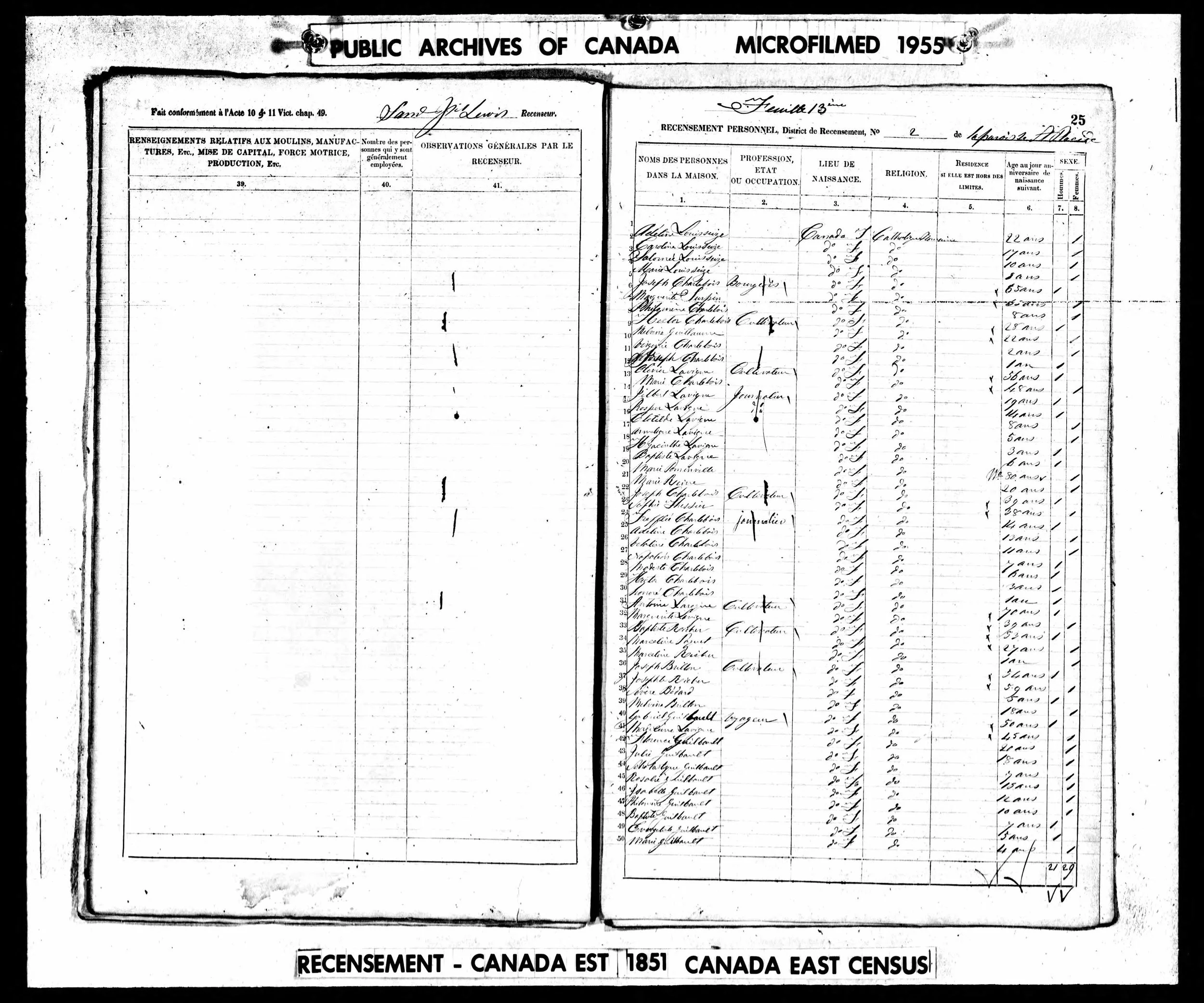

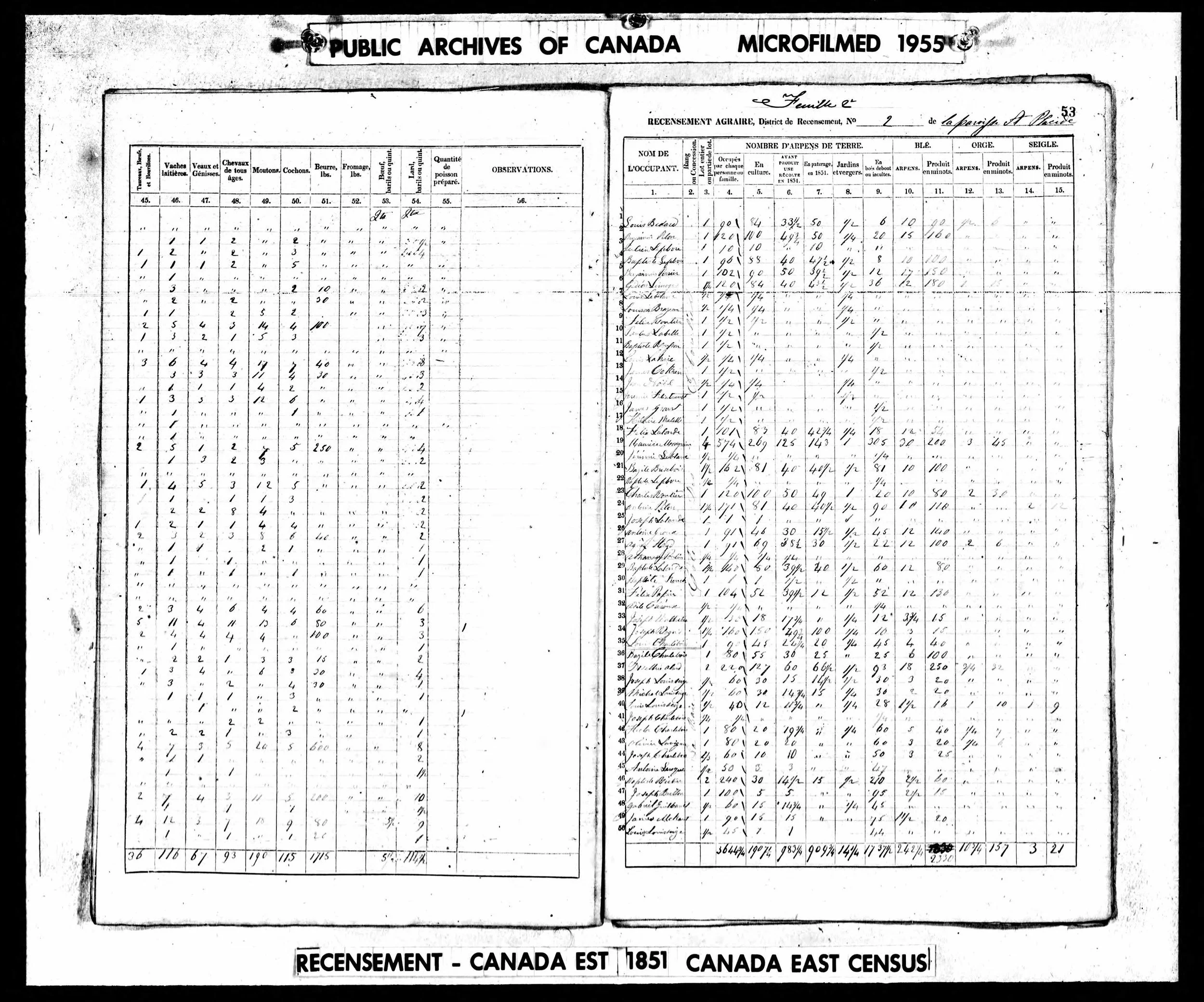

Gabriel's occupation shifts across records in a pattern that tells its own story. In 1828, when his daughter Florence was baptized, he was listed as "journalier"—day laborer. By the 1851 census, at age sixty, he was recorded as "voyageur." In 1861, at seventy, he had become "cultivateur"—farmer. The trade that should have belonged to younger men still claimed him in his sixties.

| Year | Document | Occupation | Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1828 | Baptism of Florence | Journalier | ~38 |

| 1849 | Baptism of Eloise | Cultivateur | ~59 |

| 1851 | Census of Canada East | Voyageur | 60 |

| 1861 | Census of Canada East | Cultivateur | 70 |

That 1851 census entry is striking. Gabriel was sixty years old—an age when most men had long since retired from the brutal physical demands of the canoe brigades. Yet there he was, listed as a voyageur. Perhaps he was working shorter routes, or serving as a guide drawing on decades of experience. Perhaps the designation was more about identity than active labor. But the record stands: the wilderness-born son of a voyageur was still claiming that occupation at an age when his body must have been paying the price.

The same census shows Gabriel's household in St-Placide with sixty arpents of land—a substantial farm. This was not a landless laborer. Like his father before him, Gabriel was "voyageur et agriculture," a man of the paddle who was also a man of the soil. The dual identity had passed from one generation to the next.

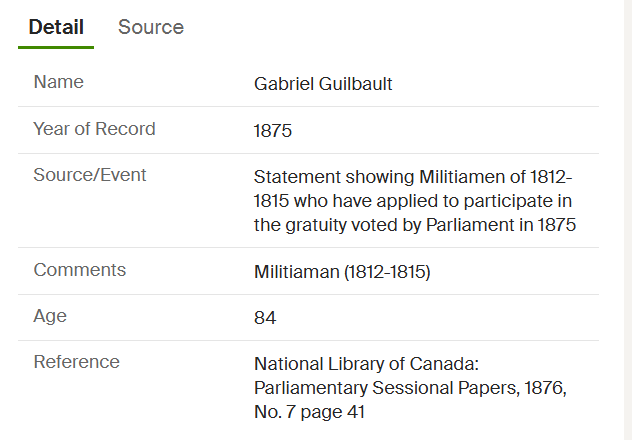

A War of 1812 Veteran

In 1875, an 84-year-old Gabriel Guilbault applied for the gratuity voted by Parliament for militiamen who had served during the War of 1812. The record confirms his service between 1812 and 1815—when Gabriel would have been approximately twenty-two to twenty-five years old. The wilderness-born son of a voyageur had defended Lower Canada against American invasion, adding yet another identity to his already complex life: soldier.

Sixteen Children

Between 1824 and 1849, Gabriel and Madeleine baptized sixteen children across four parishes. Not all survived to adulthood—the records show at least two infant deaths—but the scale of the family speaks to both the fertility patterns of the era and Gabriel's success in providing for a large household.

Children of Gabriel Guilbault and Madeleine Rocbrune

The fourteenth child, born in November 1845 at St-André-d'Argenteuil, was named Evangeliste. He would become the subject of Episode 1 in this series—the voyageur's grandson who never paddled, living his entire life as a journalier in an era when the canoe brigades had fallen silent.

Madeleine Rocbrune died on 15 December 1857 and was buried two days later at St-Placide. She was perhaps fifty-five years old, having borne sixteen children over twenty-five years of marriage. Gabriel would outlive her by more than two decades.

The Trade Passes On

The 1861 census reveals something remarkable: Gabriel's eldest son, Gabriel fils (the third Gabriel in three generations), was also listed as a voyageur. At age thirty-seven, in an era when the fur trade was dying, he carried forward the family occupation. That same year, he married Mathilde Domitille Beaudoin—not in the settled parishes of the St. Lawrence Valley, but at L'Assomption-de-la-Vierge-Marie in Maniwaki.

Maniwaki. The name itself tells the story. A mission on the Gatineau River, deep in the Ottawa Valley, Maniwaki was frontier country—the kind of place where voyageur skills still mattered, where a man who knew the rivers and the portages could still find work. The third Gabriel had gone north, following the receding edge of the fur trade into territory that his grandfather had once paddled.

A Signature in the Record

The 1861 marriage record at Maniwaki preserves something unusual: Gabriel fils signed his name. "gabriel guilbau" in a careful hand at the bottom of the page. His father—the wilderness-born Gabriel of this episode—was identified in the same record as unable to sign. The son had learned to write. Three generations from the pays d'en haut, and the Guilbaults were becoming literate.

Three generations of Gabriels. The first, a voyageur who married an Indigenous woman and brought his wilderness-born children back for baptism. The second—the subject of this episode—legitimated at ten, voyageur at sixty, patriarch of sixteen children. The third, carrying the trade to Maniwaki as it breathed its last, signing his name in a mission register while his illiterate father aged on a farm in St-André.

The Last of the Wilderness-Born

Gabriel Guilbault fils died on 7 September 1880 at St-André-d'Argenteuil. The burial record describes him as "époux de défunte Magdeleine Larocque"—husband of the late Madeleine Larocque—and estimates his age at "environ quatre-vingt douze ans," approximately ninety-two years. The witnesses were his sons Jean Baptiste and Evangeliste, who declared themselves unable to sign.

Ninety-two years. If accurate, Gabriel had been born around 1788—making him even older than the 1798 baptism record suggests. More likely, the priest estimated generously, and Gabriel was closer to ninety. Either way, he had lived an extraordinary span, from the waning years of the fur trade's golden age through the confederation of Canada and into the industrial era.

A Life in Context

He had outlived the world he was born into. The pays d'en haut of his childhood had become surveyed territory, crossed by railways, filling with settlers who had never heard a voyageur's paddle song. The canoe brigades were history. The fur trade was a memory preserved in company archives and aging men's stories. But Gabriel had been there. He had been born in the wilderness to a voyageur father and an Indigenous mother, brought back for baptism, legitimated by a priest, defended his country as a young militiaman, and lived long enough to see his own son carry the voyageur trade to its last frontier.

When Evangeliste and Jean Baptiste stood at their father's burial in 1880, they were witnessing the end of something. Not just a man, but a connection. Gabriel had been born in the pays d'en haut. His sons had been born in parishes, baptized at birth, raised as habitants. The wilderness was no longer part of their story—only an inheritance they carried in their blood and their name.

Document Gallery

Primary sources documenting Gabriel Guilbault fils

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY