Two Families, One Story: From Tailor to Farmer

From Tailor to Farmer

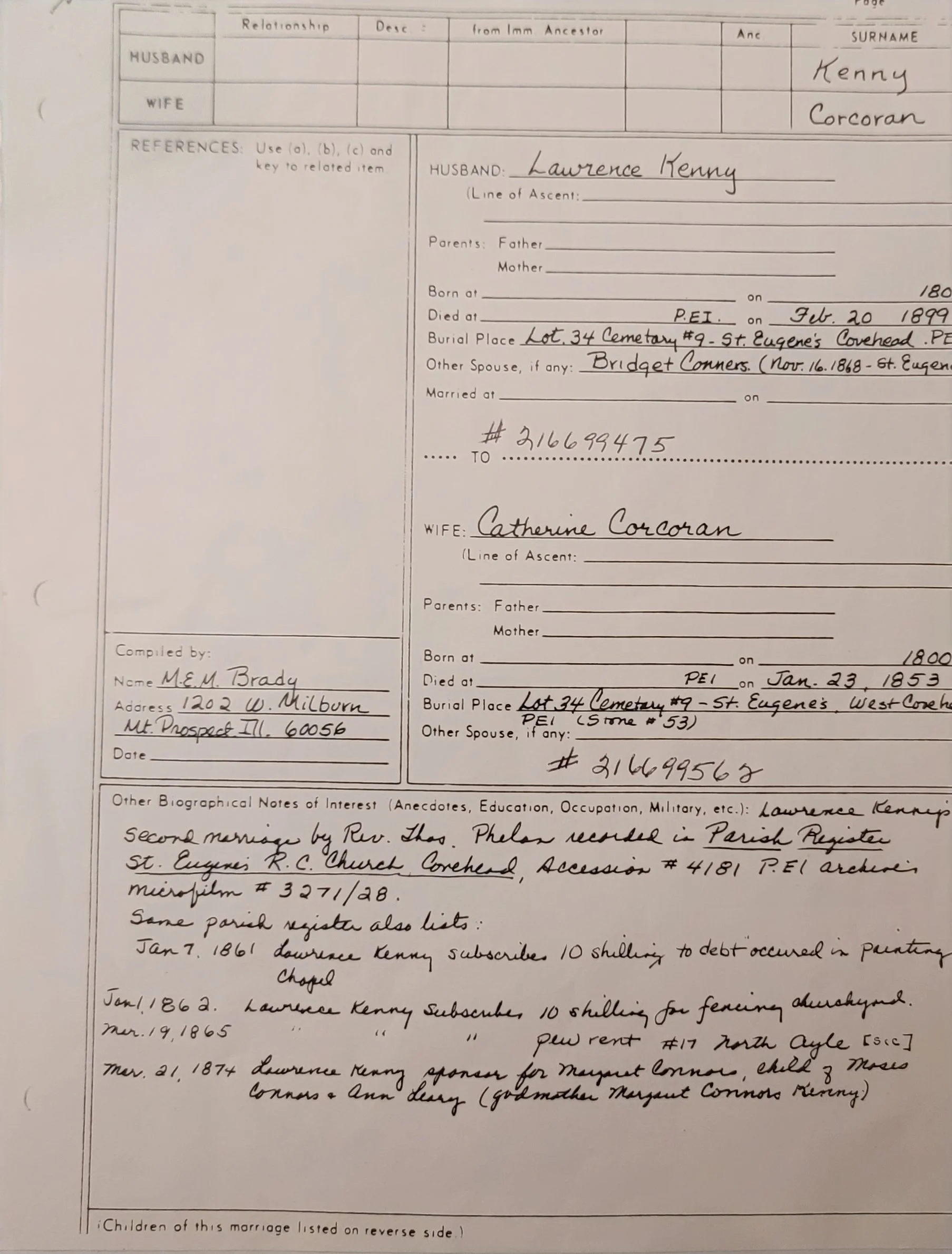

In October 1832, Lawrence Kenny brought his infant son James to St. Patrick's Church in St. John's, Newfoundland, to be baptized. The sponsors were Pierce Grace and Mary Keane—names that speak to the tight-knit Irish fishing community of the island. Within three years, Lawrence and his wife Catherine Corcoran would leave Newfoundland behind. They were heading for Prince Edward Island, where a different kind of life awaited: not fish, but soil. Not the sea, but the land.

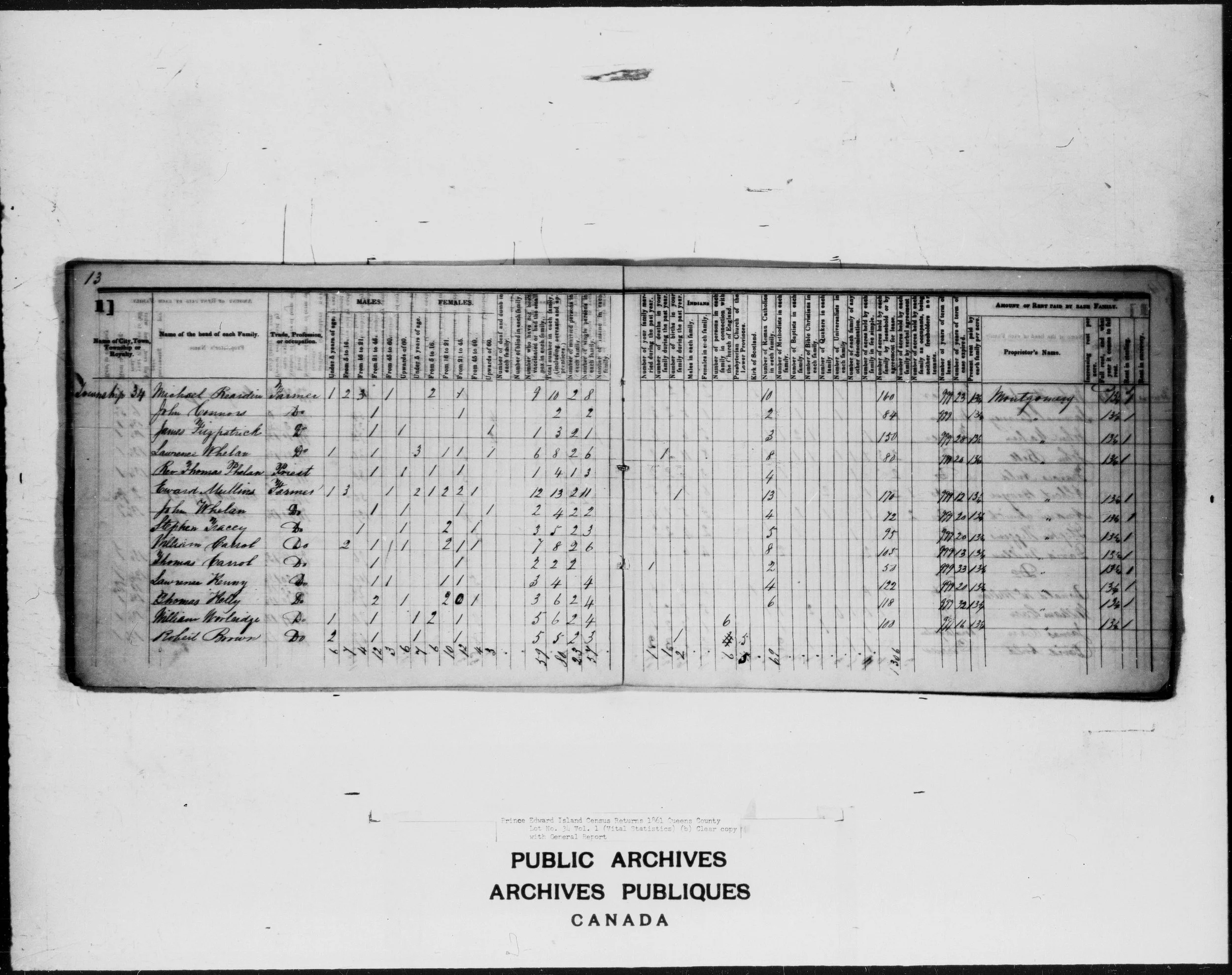

The 1841 census captures Lawrence Kenny at a pivot point in his life. He is listed as a "Tailor"—the trade he brought from Ireland, perhaps practiced in Newfoundland, and still claimed on his arrival in the colony. But by the time of the next census, that occupation would be gone. Lawrence Kenny, tailor, would become Lawrence Kenny, farmer. The transformation was complete.

The 1841 Census

Prince Edward Island

The census enumerator found Lawrence Kenny's household that year: five persons living on fifty acres, paying rent to the Montgomery Estate. The details reveal a family in transition—Irish-born parents with children born across three different jurisdictions.

The household composition tells a story of movement. Lawrence and Catherine were both born in Ireland. Their eldest known child, James, was baptized in Newfoundland in 1832—marking him as born "in the British colonies" on later records. By 1835, Alice was born in Charlottetown and baptized at St. Dunstan's on July 2nd. Bridget followed in 1839, also born in Charlottetown. The family had arrived on PEI sometime between late 1832 and July 1835.

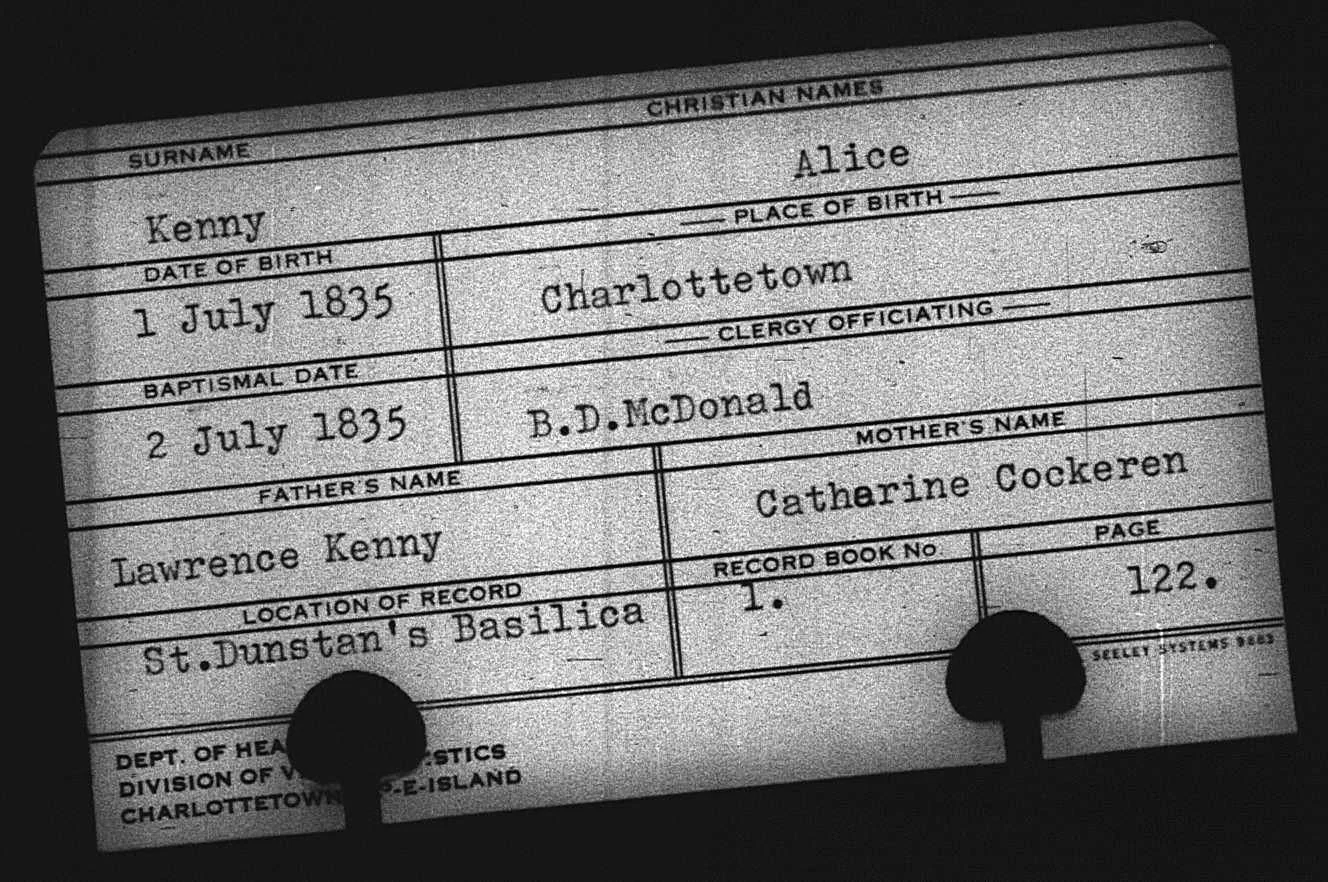

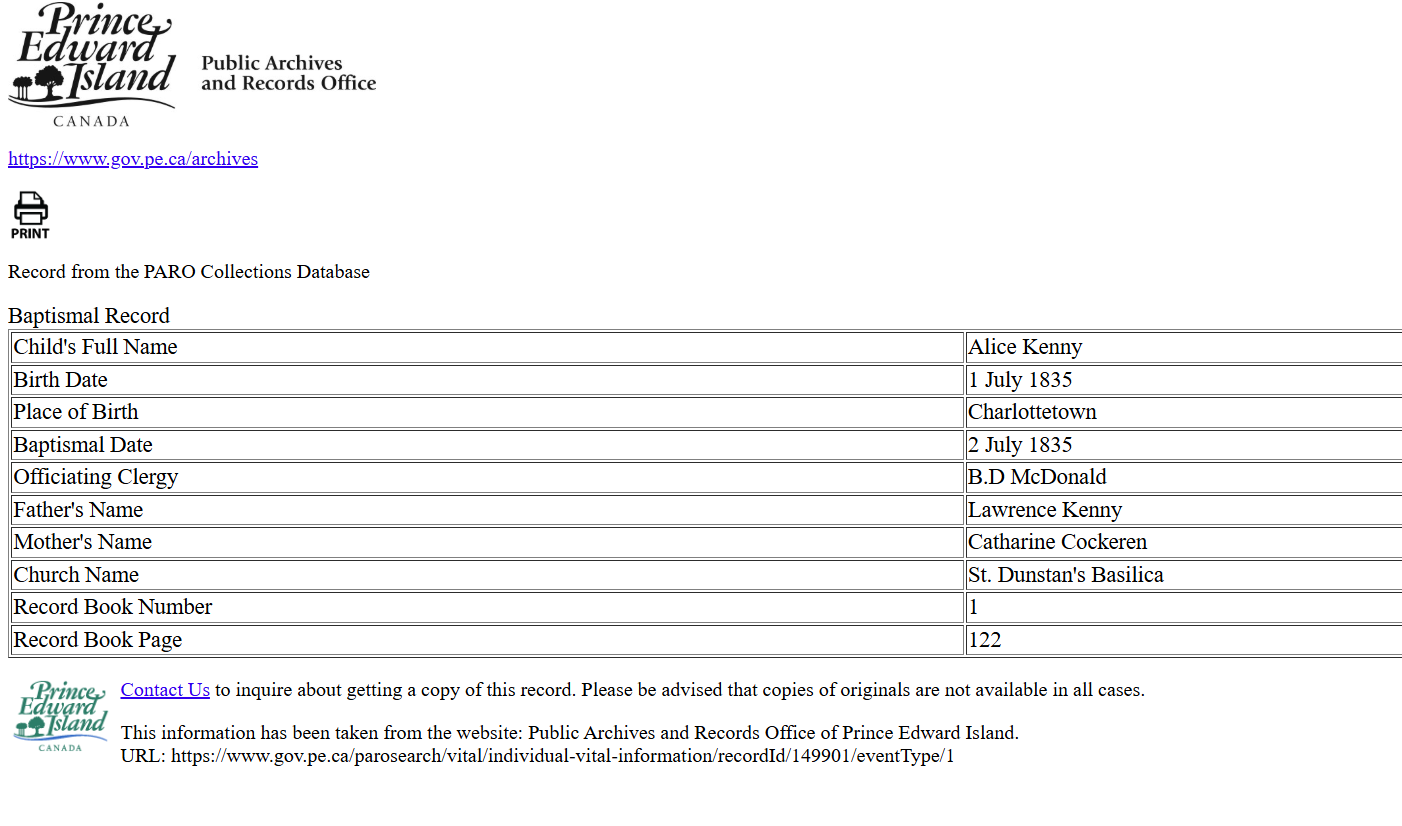

The baptism records from St. Dunstan's Basilica confirm the details. Alice Kenny, born July 1, 1835, baptized the following day by B.D. McDonald. Parents: Lawrence Kenny and Catherine Cockeren (the phonetic spelling captured by the priest). Four years later, Bridget Kenny appeared in the same register—born "3 weeks" before her March 5, 1839 baptism, officiated by Charles McDonnell.

From Tailor to Farmer

The shift from tailor to farmer was not unusual for Irish immigrants on Prince Edward Island. The skills that sustained a man in the crowded streets of an Irish town—or in the fishing settlements of Newfoundland—meant little on the cleared farmland of the Island's interior. What mattered here was the ability to work the soil, to clear forest, to raise crops and livestock.

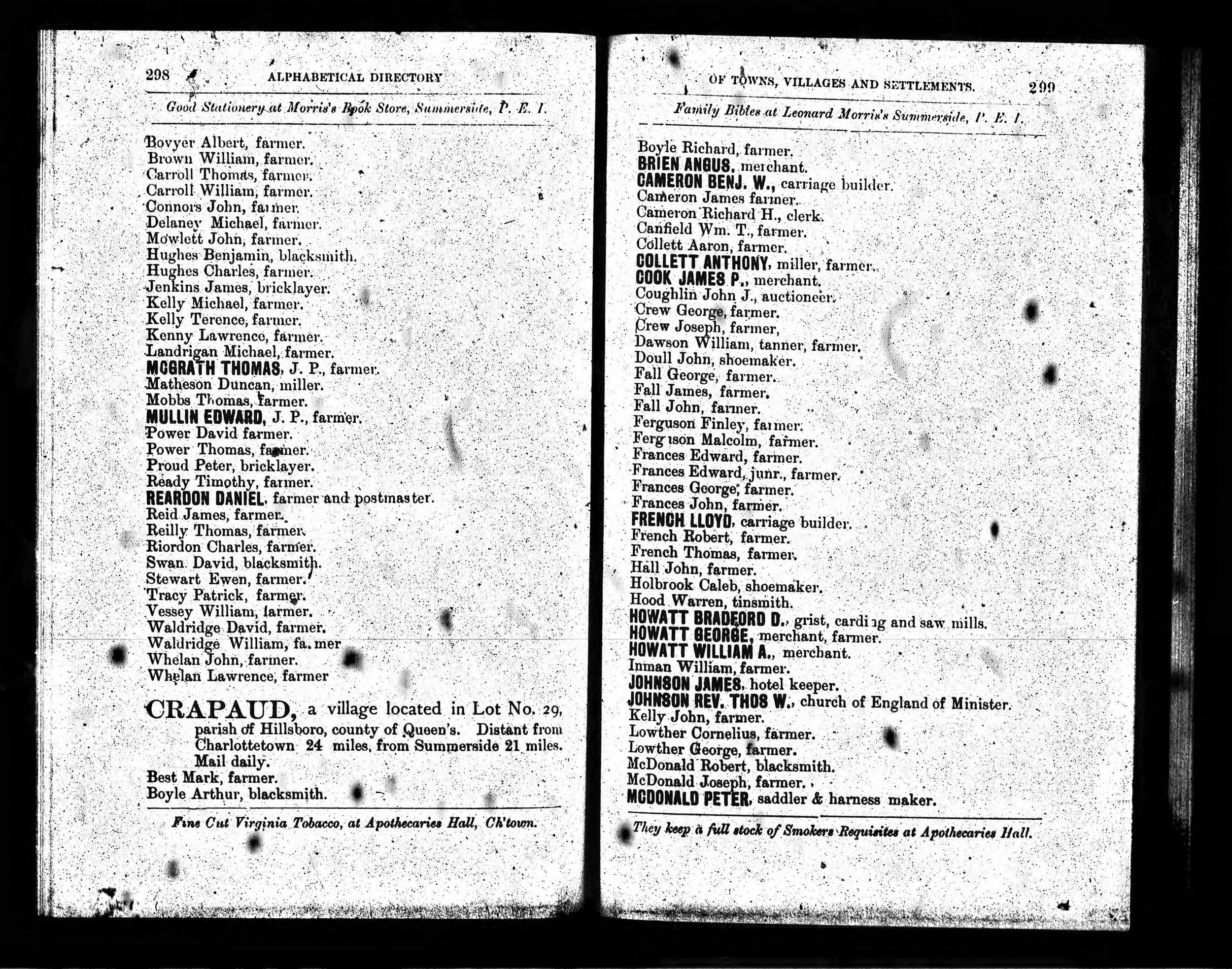

By 1861, when the next detailed census was taken, Lawrence Kenny had fully transitioned. The census lists him simply as a farmer, his tailor's needles long since set aside. The 1881 PEI Directory confirms this transformation: "Kenny Lawrence, farmer." His neighbors along the Covehead Road were farmers too—the Carrolls, the Connors, the Tracys, the Whelans. This was agricultural country.

"Lawrence Kenny, farmer" — the 1881 directory entry marked the end of a journey that began with needle and thread in Ireland and ended with plow and harrow on Prince Edward Island.

Catherine Corcoran

The spelling of her name shifted with each record: Corcoran, Cockeren, Corkeren. The phonetic challenges of recording Irish names in colonial registers ensured that Catherine's surname would appear differently depending on who held the pen. But across all records—the baptisms of her children, her husband's second marriage record, her gravestone—the pronunciation pointed to the same person.

We know remarkably little about Catherine beyond her role as wife and mother. She was born around 1800, likely in Ireland. She married Lawrence Kenny at a date and place unknown—possibly in Ireland before emigration, possibly in Newfoundland during their years there. She bore at least three children who survived to adulthood: James, Alice, and Bridget.

The Corcoran surname appears in both Wexford and Tipperary records from this period. Pierce Grace and Mary Keane, the sponsors at James Kenny's 1832 baptism in Newfoundland, bear names associated with southeast Ireland—the same region where the Connors and Kenny families may have originated. Was Catherine Corcoran part of the same emigrant network? The baptismal sponsors suggest existing community ties in St. John's.

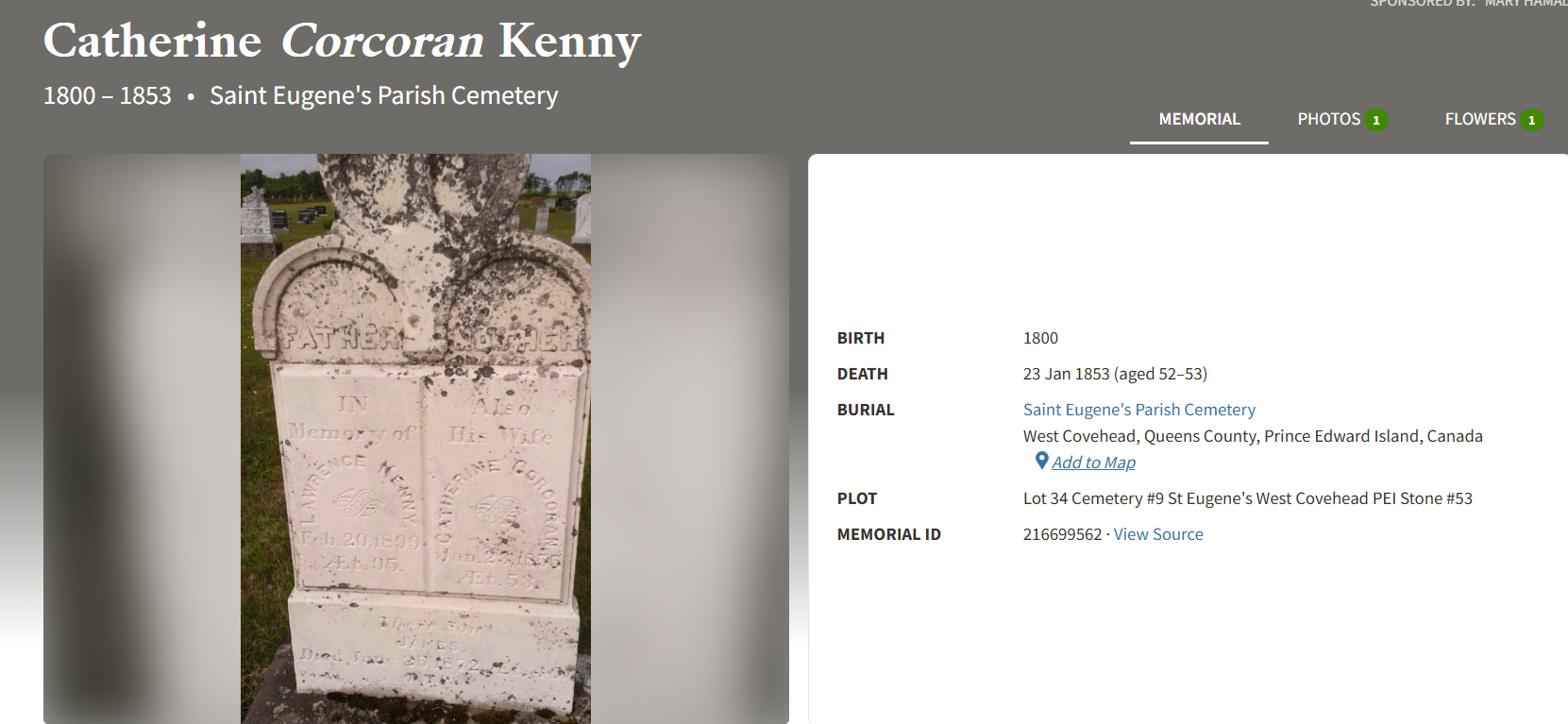

Catherine Corcoran Kenny died on January 23, 1853, at approximately 53 years of age. She was buried at St. Eugene's Parish Cemetery in West Covehead, Lot 34—the same land where she had helped establish a farm, raised her children, and watched them grow toward adulthood. Her death left Lawrence a widower with children still at home. James was roughly 21, Alice 17, Bridget 13.

The headstone that marks her grave—shared with Lawrence and their son James—records the stark facts: "Catherine Corcoran / Jan. 23, 1855 / Aet. 53." The date discrepancy (1853 vs. 1855) between family records and the stone is a common occurrence; headstones were often erected years after death, with dates sometimes misremembered.

Land and Tenancy

Lawrence Kenny never owned the land he farmed. Like most settlers on Lot 34, he was a tenant of the Montgomery Estate—part of the vast landholding system that had defined Prince Edward Island since the 1767 lottery divided the entire island among British proprietors. The Kennys paid rent: fifteen shillings per acre annually according to the 1841 census.

Daniel Hickey's 1850 cadastral map of Lot 34—officially titled "A Plan of Township No. 34, The Property of Sir Graham Montgomery & Brothers"—records Lawrence Kenny at No. 19 with 50 acres. The red ink annotations show later ownership transfers: "now Thos Carroll" indicates Thomas Carroll eventually took over the Kenny property. Significantly, Hugh Connors appears at No. 236 with 84 acres, and the notation "now John Connors" below William Riley (No. 21) shows the Connors family expanding their holdings. The families were already neighbors on the Montgomery Estate—a proximity that would matter greatly in the next generation.

The tenant system shaped everything about life on Prince Edward Island. Families like the Kennys could clear land, build homes, raise children—but they could not own what they worked. The land question dominated Island politics throughout Lawrence Kenny's lifetime. It would not be fully resolved until the Land Purchase Act of 1875, by which time Lawrence was already an elderly man.

Widowerhood and Remarriage

For fifteen years after Catherine's death, Lawrence Kenny remained a widower. He appears alone in records, an aging farmer managing his land with whatever help his children could provide. James had married Margaret Connors in 1866—one of the three Kenny-Connors marriages that would bind the families together. Alice married John O'Brien (Bryan) in 1869. Bridget had already married Edward Connors in 1867.

Then, on November 16, 1868, Lawrence Kenny married again.

His second wife was Bridget Connors. The marriage was recorded in the Parish Register of St. Eugene's RC Church, Covehead, by Rev. Thomas Phelan. Lawrence was approximately 64 years old; Bridget was about 45. This was not a marriage for founding a family—it was a practical union between two people who understood the demands of Island life.

The 1881 census shows them together: Lawrence Kenny, age 75, and Bridget, age 47. The 1891 census records continue the picture: Lawrence Kenney, age 84, Roman Catholic, Lot 34. His wife Briget Kenney, age 58, appears in the same enumeration.

The Long Life

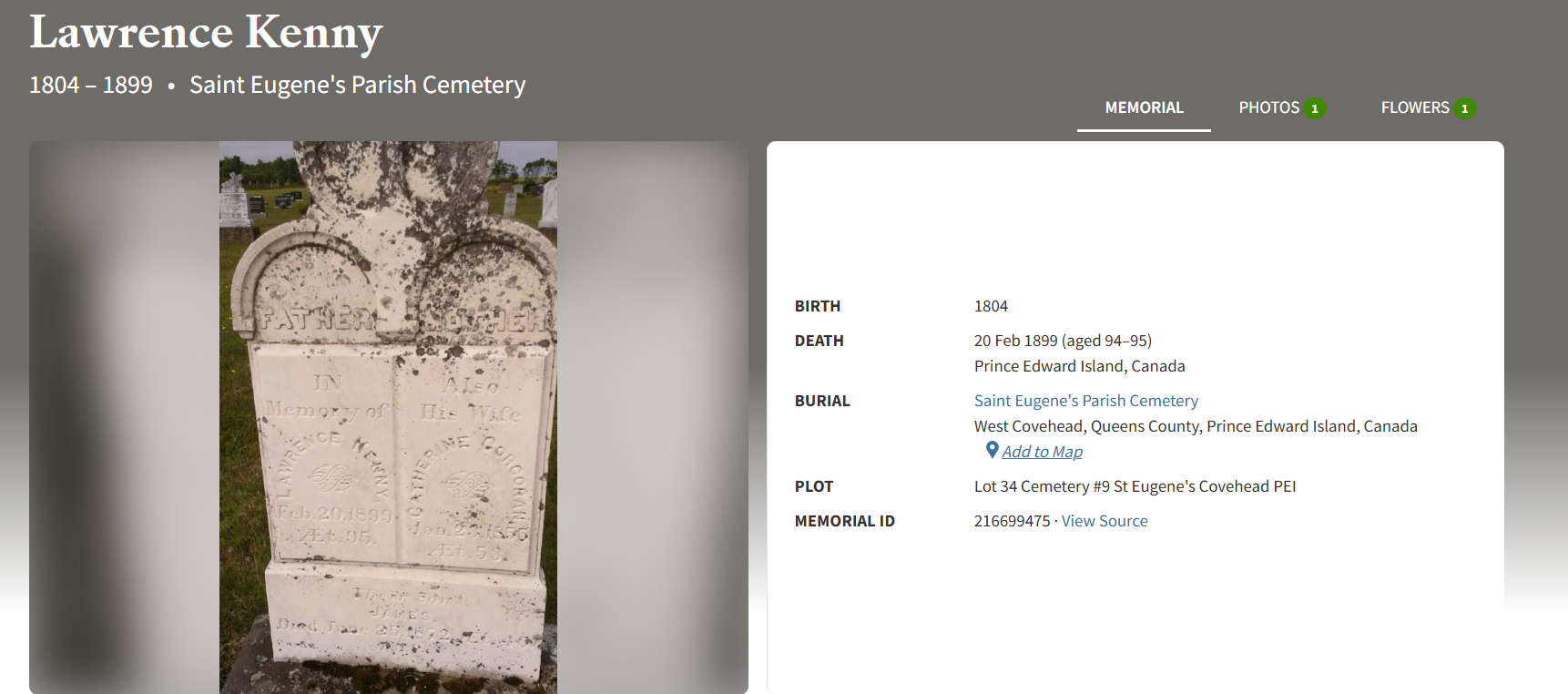

Lawrence Kenny lived to see 95 years—an extraordinary lifespan for his era. Born around 1804 in Ireland, he survived the crossing to Newfoundland, the move to Prince Edward Island, the death of his first wife, the death of his son James, and the transformation of his adopted home from colony to Canadian province.

| Census Year | Age Recorded | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1841 | ~37 | Lot 34, Township 34 | Listed as Tailor; 50 acres |

| 1861 | ~57 | Lot 34 | Listed as Farmer |

| 1881 | 75 | Lot 34 | With wife Bridget; Roman Catholic |

| 1891 | 84 | Lot 34 | Still on same land |

He died on February 20, 1899, and was buried at St. Eugene's Parish Cemetery—the same ground that held Catherine, his first wife, and James, his son who had predeceased him by 27 years. The headstone erected for the family remains there still, weathered but legible:

FATHER

In Memory of

LAWRENCE KENNY

Feb. 20, 1899

Aet. 95

MOTHER

Also His Wife

CATHERINE CORCORAN

Jan. 23, 1855

Aet. 53

Their Son

JAMES

Died June 25, 1872

The parish records note Lawrence's contributions to his church: January 7, 1861, Lawrence Kenny subscribed 10 shillings toward debt incurred in painting the chapel. January 1862, another 10 shillings for fencing the churchyard. March 19, 1865, paying pew rent for #17 North Ayle. March 21, 1874, serving as sponsor for Margaret Connors, child of Moses Connors and Ann Leary—the godmother being Margaret Connors Kenny, Lawrence's daughter-in-law.

These small entries in parish registers sketch the outline of a life lived within community: the obligations met, the ceremonies witnessed, the family connections maintained across generations.

Neighbors and Family

When Lawrence Kenny first cleared his acres on Lot 34, the Connors family was already there—or soon would be. The 1850 Hickey Map shows them both as tenants on the Montgomery Estate: Lawrence Kenny at No. 19 and Hugh Connors at No. 236. By the 1860s, their children would begin the intermarriages that would bind the families together: James Kenny to Margaret Connors (1866), Bridget Kenny to Edward Connors (1867), Alice Kenny to John O'Brien whose family had connections to both lines (1869).

Lawrence Kenny, widower, even married a Connors—Bridget—in 1868. The pattern of intermarriage that may have begun in County Wexford decades earlier had found its fullest expression on Prince Edward Island. Two families from Ireland's southeast coast, having crossed the Atlantic by different routes—one through Newfoundland, one through New Brunswick—converged on fifty acres in Queen's County and became, through marriage, one extended family.

Document Gallery

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY