Ojibwe Baskets, Beads, and Art

A STORYLINE GENEALOGY DISCOVERY

Ojibwe Baskets, Beads, and Art

A Genealogist's Discovery

In Honor of Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe

Floral designs created by Ojibwe artists represent the flowers and plants

found close to their woodland homes in the Great Lakes region.

"Part of my process of researching ancestors is that when I discover their location of origin, I search for some type of historical map or artifact or art from that area as a tangible connection to them."

When I discovered my Ojibwe 4th great-grandmother, Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe, I wasn't prepared for how profoundly that discovery would change the way I understood my family's history. For generations, she had existed only as a shadow in the records—"Sauvagesse," the wife of voyageur Gabriel Guilbault. No name. No story. No identity beyond a generic French term meaning "Indigenous woman."

Then, in a marriage record from 1801, preserved at L'Annonciation in Oka, Quebec, a priest had written her full Ojibwe name: Abitakijikokwe—a name with the suffix "-ikwe" meaning "woman" in the Ojibwe language. After 200 years of silence, she emerged from the records with her Indigenous identity intact.

And so began my journey into the world of Ojibwe art—searching for tangible connections to the woman who founded my Métis family line.

The Pays d'en Haut: Marie Josephte's World

Marie Josephte lived during the era of the Pays d'en Haut—the "Upper Country"—the vast French colonial fur trade territory stretching around the Great Lakes. The Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) were central to this world, acting as key allies, trading partners, and participants in the complex diplomatic networks that shaped the region's history.

A 1755 map by Jacques Nicolas Bellin showing the Great Lakes region—the Pays d'en Haut.

This territory was dominated by various Indigenous nations though nominally under French influence,

with the Ojibwe among the most important trading partners.

The Ojibwe were part of the Anishinaabeg—the Council of Three Fires—an alliance with the Odawa and Potawatomi that controlled much of the Great Lakes trade. The Straits of Mackinac (Michilimackinac) served as a vital fur trade hub where Ojibwe, Odawa, and French-Canadian voyageurs interacted, creating the complex community dynamics that would eventually produce the Métis people.

It was in this world that Gabriel Guilbault, a French-Canadian voyageur, met Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe around 1789. Their union began "à la façon du pays"—according to the custom of the country—a marriage recognized by Indigenous tradition though not yet by the Catholic Church. The unions of Ojibwe women with French traders created Métis families and communities, enriching the cultural tapestry of the Upper Country.

The Art of Ojibwe Beadwork

Beadwork is one of the most distinctive characteristics of Ojibwe artistic expression. Before European contact, Ojibwe women decorated clothing and regalia with shells, dyed porcupine quills, bird quills, bone, seeds, and paint. The techniques were sophisticated and the designs held deep meaning.

The fur trade transformed this tradition. Glass beads, introduced to the Ojibwe in the 1600s, revolutionized their decorative arts. Most glass beads used in the fur trade were made in Murano, near Venice, Italy, with other beadmaking centers in Holland and Bohemia. These vibrant trade goods replaced quillwork and natural materials, allowing artists to create increasingly intricate designs.

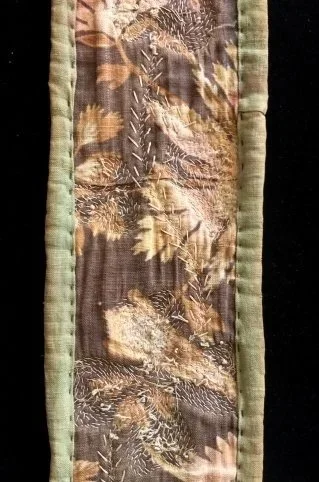

19th century Great Lakes bandolier bag strap, possibly Ojibwe.

Nine different colors of seed beads create a lyrical floral design

on dark blue woolen trade cloth.

The back reveals early 19th century printed trade cloth—

evidence of the material exchange between

European traders and Indigenous communities.

Ojibwe artists developed two primary beadwork techniques. In spot-stitch embroidery, strands of beads are stitched to the surface every two or three beads. The beadworker follows the motif's outline, working freehand from the outer edge to the center—creating the flowing, curvilinear floral designs that became the Ojibwe signature style. In contrast, loom-woven beadwork employs linen or cotton thread on a rectangular frame, producing geometric designs in a technique called square weave.

One beautiful tradition that continues today is the "spirit bead"—a single differently colored bead intentionally placed within the design. This symbolizes the belief that only the Creator is perfect; the spirit bead is an act of humility woven into the art itself.

The Ayer Collection: Preserving a Legacy

One of the most significant collections of Ojibwe beadwork resides at the Minnesota Historical Society, thanks to Harry and Jeannette Ayer. The Minnesotans moved to the Mille Lacs area sometime between 1914 and 1919, taking over a trading post on Vineland Bay that had been formerly run by David H. Robbins.

In 1918, the United States Indian Service granted the Ayers a license to trade with the Mille Lacs Ojibway. The Ayers ordered merchandise from bead supply companies that imported their beads from European manufacturers, and the Mille Lacs Ojibway purchased beads, velvet, thread, needles, braid, cloth, and ribbon at the post. Entries relating to the production of beaded items appear frequently in the trading post ledgers throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

The Ayers became neighbors, friends, employers, and vendors for the Ojibway at Mille Lacs. Harry Ayer served as mediator, executor, and administrator of Ojibway estates, and occasionally acted as their spokesman to White Earth agents. In 1959, seven years before their deaths, Mr. and Mrs. Ayer donated their entire estate to the Minnesota Historical Society—104 acres of land, the trading post, a new building, and a trust fund to support and expand the museum.

The Gift of Birch Bark

The paper birch tree provided the Ojibwe with one of their most versatile materials. From birch bark, they crafted canoes lightweight enough to carry across portages and easily maneuvered through the lakes and rivers of the Great Lakes region. These vessels were specially suited to the landscape—and because they were made of materials readily available in the region's forests, they could be easily repaired if damaged.

Birch bark baskets—functional art that connected

daily life to the surrounding forest.

Canoes were not only transportation but also devices for gathering food. When harvesting manoomin (wild rice), Ojibwe people used their canoes to catch the rice grains knocked from the plants with special knocking sticks. In early spring, canoes may have been used to collect sap for processing into ziinzibaakwad, maple sugar.

Beyond canoes, birch bark was fashioned into makuk containers—trays, baskets, and boxes for everyday use. But perhaps most remarkably, birch bark served as a writing material for the wiigwaasabakoon (birch bark scrolls), on which the Ojibwe recorded complex geometrical patterns, songs, healing recipes, and ceremonial knowledge.

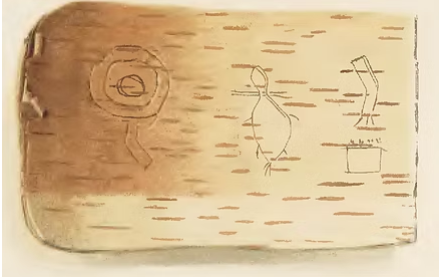

Birch bark scroll from the Smithsonian Institution,

U.S. Bureau of Ethnology Report on "The Midewiwin,

or 'Grand Medicine Society', of the Ojibwa."

Makuk containers made of birch bark.

Photo by Doug Coldwell.

The bark of the paper birch provides excellent writing material. A stylus of bone, metal, or wood inscribes ideographs on the soft inner bark, with black charcoal often used to fill the scratches for visibility. Pieces of inscribed bark are stitched together using wadab (cedar or spruce roots), then placed in cylindrically-shaped wiigwaasi-makak (birch bark boxes) for safekeeping.

Scrolls were recopied over generations and stored in dry locations—often underground in special containers or in caves. Elders kept them hidden to avoid improper interpretations and to protect the teachings from disrespect. When used for Midewiwin ceremonial purposes, these scrolls are called mide-wiigwaas—enabling the memorization of complex ideas and the passing of history and stories to succeeding generations.

Asabikeshiinh: The Dreamcatcher

In Ojibwe, the dreamcatcher is called asabikeshiinh—the inanimate form of the word for "spider." Originally known as the "spider web charm" (asubakacin, meaning "net-like"), it was a handmade willow hoop with a woven net or web, traditionally hung over cradles or beds as protection for infants.

A traditional dreamcatcher—asabikeshiinh in Ojibwe—

hung over cradles as protection, inspired by

the story of the spider woman.

While dreamcatchers continue to be used traditionally in their communities of origin, the Pan-Indian movement of the 1960s and 1970s adopted them as a symbol of unity among various Indigenous cultures. By the 1990s, they had become widely popular—though many Indigenous communities view commercially produced imitations as appropriation of their cultural heritage.

Eddy Cobiness: A Contemporary Master

In my search for tangible connections to Ojibwe art, I discovered the work of Eddy Cobiness—a leading figure in contemporary Indigenous art from Buffalo Point Reserve in eastern Manitoba.

Although he began painting early in life, it was only after years of devoted practice that he made his art a full-time calling. Most of his work is done outdoors near his home, where he works amid the elements and living things closest to him. His talent ranges from portraits to rural scenes, from contemporary Indian art to surrealist work, appearing in calendars, books, and illustrations.

Eddy Cobiness, "Grouse Family"—prints from my personal collection.

His work combines sophistication of composition

with a flowing naturalness of line and movement.

Using media such as coloured pencil, pen and ink, acrylic, oil, and watercolour, Cobiness produces distinctive works that combine sophistication of composition with a flowing naturalness of line and movement. His art has made headlines across major Canadian cities, with demand for his prints exceeding production. He constantly shows his originals in galleries across Canada.

I own two of his prints—a pair featuring grouse families that hang in my home. They represent for me the continuation of Ojibwe artistic traditions into the present day, a living connection to the culture of my ancestor Marie Josephte.

Tangible Connections: My Discoveries

In addition to the Eddy Cobiness prints, my search for tangible connections to Marie Josephte led me to antique Ojibwe pieces. On eBay, I found two treasures that now hold places of honor in my home.

My antique Chippewa Ojibwe beaded velvet purse and birch bark basket—

tangible connections to my Ojibwe heritage through Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe.

The first is an antique Chippewa Ojibwe Woodlands beaded velvet purse—a small piece decorated with spot-stitch floral beadwork in the traditional style. The branching stem with flowers and leaves against black velvet follows the same artistic traditions that have been passed down for centuries. The second is a petite birch bark basket—a small container that represents the everyday utility and artistry of birch bark work.

These pieces aren't museum artifacts behind glass. They're objects I can hold in my hands—objects created by Ojibwe artists using techniques their ancestors perfected over generations. When I touch the beadwork, I'm connecting to the same artistic traditions Marie Josephte would have known. When I hold the birch bark basket, I'm holding a piece of the same material culture that shaped her daily life in the Pays d'en Haut.

Why This Matters

Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe represents thousands of Indigenous women who formed the foundation of Métis families across the Great Lakes region. These women maintained the kinship networks that made the fur trade possible, raised children between two worlds, and created a new people—the Métis.

For 200 years, she existed only as "Sauvagesse" in family trees—another woman lost to family memory through centuries of distance from original records. But because priests and notaries recorded her Indigenous identity rather than erasing it, her story survived. Her name survived. And through that name, I found my way back to her world.

The beadwork, the birch bark, the art—these aren't just historical artifacts. They're living traditions that connect me to Marie Josephte and to the Ojibwe culture that shaped her life. They're tangible proof that my ancestors came from a real place with real traditions, real artistry, and real meaning.

When I look at the Eddy Cobiness prints on my wall, or hold the antique beaded purse in my hands, I'm not just appreciating beautiful objects. I'm honoring a woman who emerged from 200 years of silence—and I'm keeping her memory alive.

For Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe (c. 1770–1813)

Ojibwe wife of Gabriel Guilbault • Mother of six children

My 4th great-grandmother

Related Reading

Finding Marie Josephte: How One Ojibwe Woman Emerged from 200 Years of Silence →

The full story of discovering my 4th great-grandmother's identity in Quebec parish records.

The Guilbault Line: A Documentary Biography →

The complete case study tracing the voyageur family from Quebec to the present.

Episode 3: Gabriel Guilbault père — The Original Voyageur →

The full story of Gabriel Guilbault 1762-1833

Perthshire Paperweights: A Genealogist's Discovery →

Part of "A Genealogist's Discovery" -a companion piece on tangible connections

Sources

Anderson, Marcia G. and Kathy L. Hussey-Arntson. "Ojibway Beadwork Traditions in the Ayer Collections." Minnesota History (Winter 1982): 153-157.

"The Midewiwin, or 'Grand Medicine Society', of the Ojibwa." Smithsonian Institution, U.S. Bureau of Ethnology Report.

Bellin, Jacques Nicolas. "Partie Occidentale de la Nouvelle France ou du Canada." 1755. Homann Heirs Atlas Major.

Additional materials from Minnesota Historical Society, Ojibwe cultural resources, and primary source documents from the Archives Nationales du Quebec.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY