Finding Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe

Finding Marie Josephte: How One Ojibwe Woman Emerged from Two Centuries of Silence

The Woman Without a Name

For generations, she existed only as a shadow in our family tree—"Sauvagesse," the wife of Gabriel Guilbault. No name. No story. No identity beyond the generic French term for "Indigenous woman."

But Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe was about to speak from the past.

The Search Begins

This research began in 2018 and spanned six years of systematic investigation across multiple archives. What started as a seemingly impossible quest—finding a woman listed only as 'Sauvagesse'—became a methodical process of parish-by-parish searching, linguistic analysis, and pattern recognition. The breakthrough didn't come until 2024, when new search technologies finally revealed what had been hiding in plain sight for over two centuries.

The obstacles seemed insurmountable:

- No civil registration existed for Indigenous marriages before the 1800s

- Catholic priests typically recorded Indigenous women only as "Sauvagesse"

- Fifteen different spellings of Guilbault scattered records across parishes

- The family moved frequently along the Quebec-Ontario border

- French paleography, Latin formulas, and Ojibwe names created linguistic puzzles

Then FamilySearch Full Text Search feature changed everything.

The Breakthrough: When Technology Meets Tenacity

The new Full Text Search feature on FamilySearch allowed me to search within the actual handwritten content of documents—not just indexed names. Suddenly, I could search for "Sauvagesse" and "Sauteuse" within the documents themselves.

October 10, 1798 — St-Paul-de-Joliette

Three children baptized together. The mother:

"Josephte Sauvagesse, Sauteuse"

Not just Indigenous. Specifically Ojibwe/Saulteaux.

This wasn't just a woman anymore—this was a member of a specific nation, and the priest had recorded it.

January 27, 1801 — L'Annonciation, Oka

The marriage record that changed everything:

"Gabriel Guilbau and M. Josephte Abitakijkok8e"

Her name. Her full Ojibwe name, preserved by a Catholic priest who chose to record rather than erase it. The suffix "-ikwe"—meaning "woman" in Ojibwe—confirmed the authenticity: this was her actual Indigenous name, not a French approximation.

Bringing Marie Josephte to Life

Through painstaking research across five parishes, fifteen documents emerged spanning nearly a century. Each one confirmed what the marriage record revealed: Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe was real, she was Ojibwe, and her identity had survived.

Her Story Unfolds

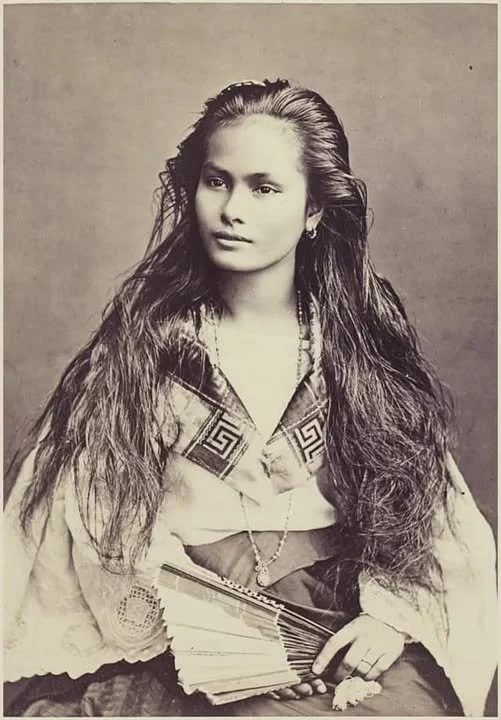

The Face of History

Looking at historical photographs from her era, I see strength, dignity, and resilience. When my daughter's features echo those in these old images, I wonder if we're seeing Marie Josephte's legacy written in our faces as surely as it's written in parish registers.

Why This Discovery Matters

Marie Josephte's story is more than personal genealogy—it's a reclamation. Her documented existence challenges the narrative that Indigenous women in colonial records are forever "lost."

The Exceptional Nature of This Documentation

In my years of genealogical research, I've learned that very few Indigenous ancestors have names recorded, even fewer have tribal affiliation specified.

Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe stands as one of the best-documented Indigenous women in Quebec parish records.

Lessons for Other Researchers

Your "nameless" ancestor may be findable. Here's what worked:

- Use Full Text Search: FamilySearch's new feature searches within documents, not just indexes

- Learn the Language: "Sauvagesse," "de nation," and tribal names like "Sauteuse" are your clues

- Map the Fur Trade: Focus on Oka, Kanesatake, Deux-Montagnes, and other known Métis communities

- Follow the Children: Mass baptisms often reveal family groups

- Check Legal Documents: Notarial records preserve identities long after death

- Understand the Context: Relationships "à la façon du pays" were often formalized years later. This means the church marriage date doesn't indicate when the relationship began—look for earlier births to establish the actual family formation timeline

Want a systematic approach to finding Indigenous ancestors? The strategies that uncovered Marie Josephte's identity can work for other 'nameless' ancestors—see the guide linked at the end of this post for a comprehensive approach to recognizing patterns in Quebec parish records.

The Living Legacy

Today, Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe's descendants carry forward a documented Métis heritage. We are the living proof of her existence, the continuation of a story that survived two centuries not because colonial records erased her, but because a few priests chose to document rather than obscure Indigenous identity.

Her legacy lives not just in DNA but in the resilience she passed down—the ability to maintain identity across generations, to preserve culture through centuries of change, to bridge two worlds while belonging fully to both.

Part of The Guilbault Line

Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe's story connects to Episode 3: Gabriel Guilbault, Le Voyageur—the man who paddled into the pays d'en haut and a priest who chose to record his Ojibwe wife's name for posterity.

Your Story Awaits

Every family searching for Indigenous ancestors deserves what I found—the name, the story, the proof that transforms "unknown" into known, "obscured" into recovered.

Marie Josephte waited more than two centuries to be found.

Your ancestor may be waiting too.

Ready to Find Your Own Hidden Heritage?

If you have French-Canadian ancestry with mysterious gaps, unnamed women, or fur trade connections, your Indigenous ancestors may be discoverable in colonial records.

This case study is part of the Storyline Genealogy series documenting exceptional genealogical discoveries. Storyline Genealogy specializes in Métis and Indigenous ancestry research, transforming 'nameless' ancestors into documented matriarchs and patriarchs through systematic research in Quebec parish records.

Footnotes

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY