The Guilbault Line: Gabriel Guilbault pere

Gabriel Guilbault père

A Life Spanning Two Worlds

Gabriel Guilbault was born into the rhythms of New France—a world of parish bells, seigneurial farms, and the promise of adventure in the pays d'en haut. He would live to see that world transform, from French colony to British possession to the Rebellion year of 1833. Along the way, he would paddle canoes laden with furs, marry an Ojibwe woman who gave him a Métis family, bury a wife and several children, remarry, acquire land, and finally rest in the parish cemetery of St-Benoît.

His story is not one of fame or fortune. It is the story of ordinary survival—of a man navigating the dangerous waters of the fur trade and the equally treacherous currents of colonial change. Yet in the documents he left behind, we find something extraordinary: the preservation of an Indigenous woman's name and identity across more than a century of records.

Origins: L'Assomption, 1762

On June 13, 1762, in the parish of L'Assomption northeast of Montreal, a boy was baptized Gabriel. The register recorded his parents as Gabriel Gibbort (a phonetic rendering of Guilbault) and Marie Charlotte Morin. It was the final year of the Seven Years' War—within months, the Treaty of Paris would transfer New France to British control.

L'Assomption sat at the junction of the L'Assomption River and the St. Lawrence trade routes, making it a natural launching point for the voyageurs who paddled west each spring. Young Gabriel would have grown up watching the brigades depart, their canoes loaded with trade goods, their songs echoing across the water.

"Le dix octobre mil sept cent soixante deux... a été baptisé Gabriel né d'aujourd'hui du légitime mariage de Gabriel Gibbort et de Marie Charlotte Morin..."

— L'Assomption Parish Register, June 13, 1762By the 1780s, Gabriel had joined their ranks. The fur trade offered young French-Canadian men something farm life could not: adventure, independence, and the chance to see the world beyond the parish boundaries. It also offered something else—intimate contact with Indigenous peoples whose labor, knowledge, and kinship networks made the trade possible.

Into the Pays d'en Haut

The pays d'en haut—the "upper country"—stretched from the Ottawa River to Lake Superior and beyond. It was a world of portages and rapids, of winter camps and summer rendezvous, of business conducted in a mixture of French, English, and Algonquian languages.

Gabriel Guilbault entered this world as a voyageur, one of the men who paddled the great canoes that connected Montreal to the interior. The work was grueling: eighteen-hour days of paddling, loads of 180 pounds carried across portages, diets of dried corn and grease. But it was also a life of relative freedom, far from the social constraints of the settled parishes.

À la Façon du Pays

Sometime around 1789-1790, Gabriel formed a relationship with a young Ojibwe woman. Such unions were common in the fur trade—marriages à la façon du pays (marriages according to the custom of the country) created bonds between French-Canadian traders and Indigenous communities that facilitated commerce and survival alike.

Her people, the Saulteaux or Ojibwe, controlled the territory around Lake Superior and the upper Ottawa River. Her knowledge of the land, her family's trading connections, and her labor processing furs would have been invaluable to a young voyageur trying to establish himself in the trade.

For over a decade, she would remain unnamed in any surviving record—just another "Sauvagesse" in the colonial archives. But she was about to become one of the best-documented Indigenous women in Quebec parish records.

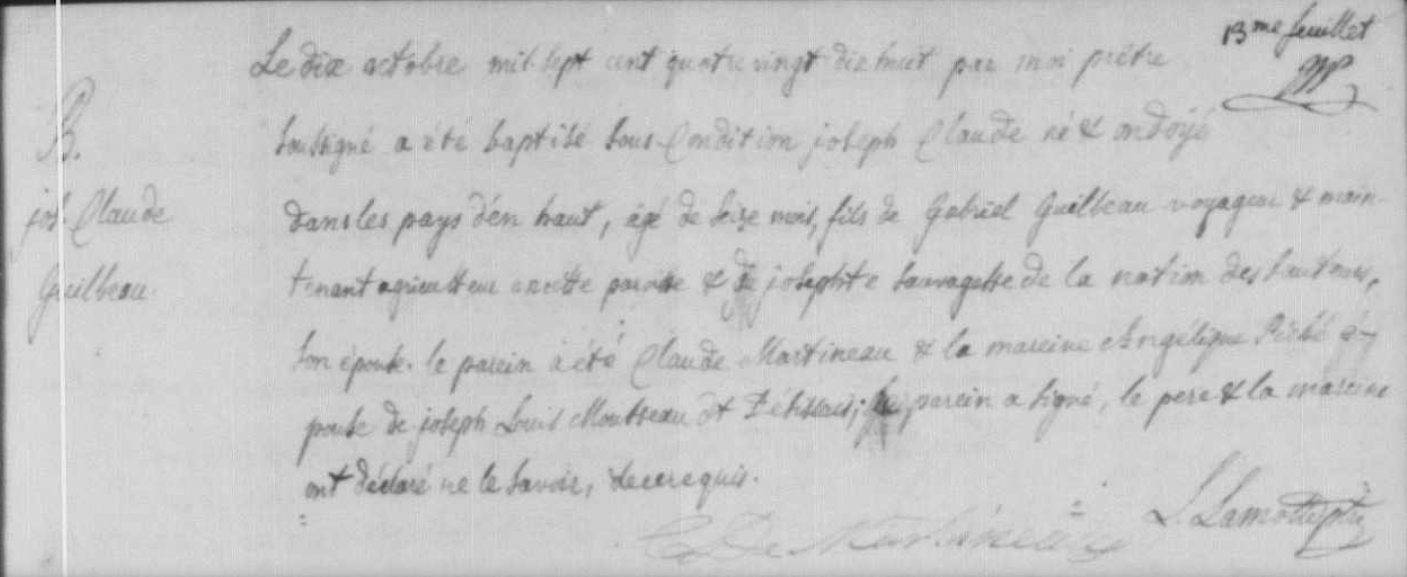

October 10, 1798: The Mass Baptism

By the late 1790s, Gabriel and his family had settled near St-Paul-de-Joliette, and he had transitioned from voyageur to agriculteur—farmer. On October 10, 1798, he brought three of his children to the parish church for baptism.

The priest recorded them one after another:

And then the crucial detail. The priest did not simply write "Sauvagesse." He wrote: "Josephte Sauvagesse de la nation des Sauteux"—Josephte, Indigenous woman of the Ojibwe/Saulteaux nation.

This tribal identification was the key that would unlock everything.

January 27, 1801: A Name Preserved

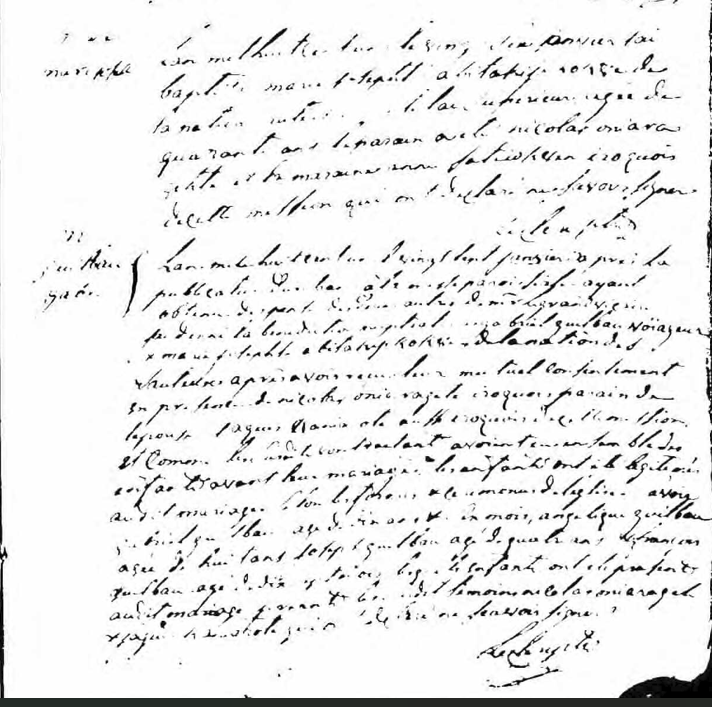

Three months into the new century, Gabriel and Josephte traveled to L'Annonciation at Oka to formalize their union before the Catholic Church. After eleven years and four children, they would finally have a church wedding—and their children would be legitimized.

What happened next was remarkable. The priest, Father Leclerc, did something unusual: he preserved her full Ojibwe name.

The day before the wedding, January 26, Marie Josephte received Catholic baptism. The register reads: "Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur"—of the Ojibwe nation on Lake Superior, approximately 40 years old.

Her godparents were both Indigenous: Nicolas Oniaragehte and Anne Satioksen, Iroquois of the Oka mission. The following day, the marriage was celebrated with Indigenous witnesses—Nicolas Oniaragehte (her godfather) and Jaques Kaniarote, also Iroquois.

The suffix "-ikwe" in her name means "woman" in Ojibwe. This was her actual Indigenous name, not a French approximation—proof that Father Leclerc took the time to record her identity accurately.

The register also documents the legitimization of their four children: Gabriel (10 years 6 months), Angélique (8 years), Joseph (4 years), and François (17 months). A family that had existed for over a decade "à la façon du pays" was now formally recognized by the Church.

The First Family: Life and Loss

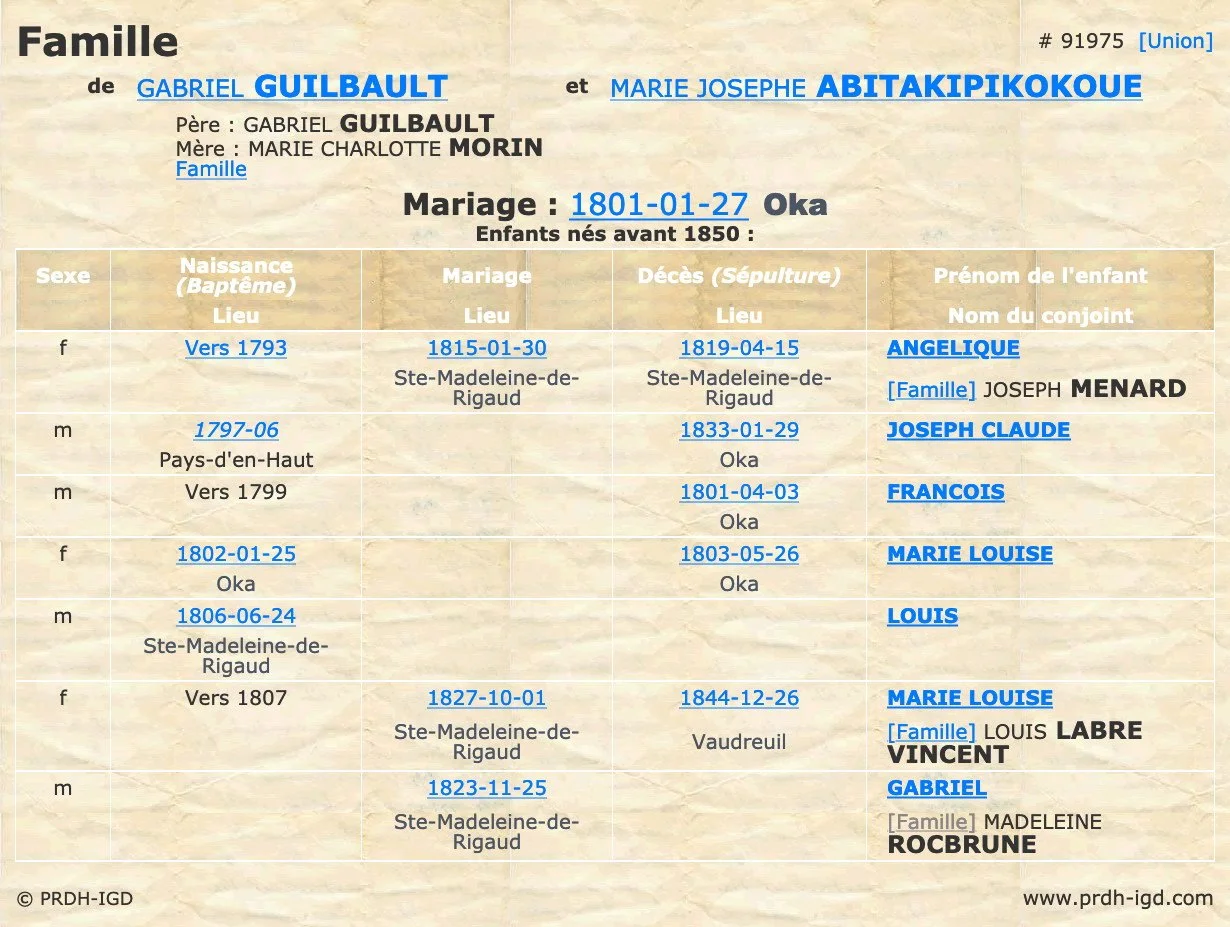

Between approximately 1790 and 1807, Gabriel and Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe had seven children. The PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique) database documents their family:

| Child | Born | Location | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gabriel Jr. | ~1790 | Pays-d'en-Haut | Married Madeleine Rocbrune, 1823 |

| Angélique | ~1793 | Pays-d'en-Haut | Married Joseph Menard, 1815; died 1819 |

| Joseph Claude | June 1797 | Pays-d'en-Haut | Died January 1833, Oka |

| François | Sept 1799 | St-Paul-de-Joliette | Died April 3, 1801 (age 18 months) |

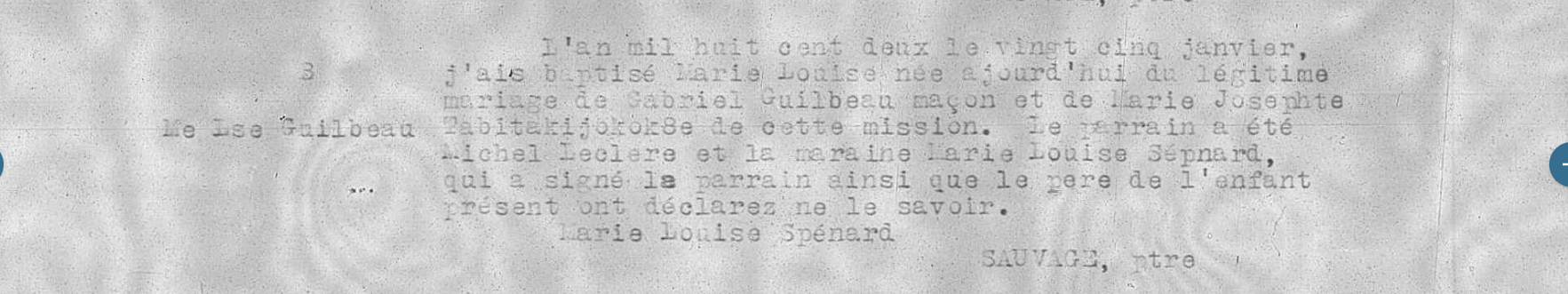

| Marie Louise | Jan 1802 | Oka | Died May 26, 1803 (age 16 months) |

| Louis | June 1806 | Ste-Madeleine-de-Rigaud | Survived to adulthood |

| Marie Louise | ~1807 | Ste-Madeleine-de-Rigaud | Married Louis Labre Vincent, 1827 |

The burial records of the two children who died young preserve Marie Josephte's name in various spellings—evidence of French priests trying to phonetically capture an Ojibwe name: "Abitakijikokwe," "Abitakijikok8e," "Tabitakijokoke." Each variation is another thread connecting us to a real woman.

Career Evolution: Voyageur to Maçon

Gabriel's occupational journey mirrors the changing economy of Lower Canada. The parish records track his transformation:

This progression—from itinerant paddler to settled tradesman to property owner—represents the classic arc of a successful voyageur. Many never made it this far, dying young from accidents, exposure, or disease. Gabriel's survival and prosperity speak to resilience, adaptability, and perhaps some luck.

June 25, 1813: Farewell to Marie Josephte

After more than two decades together, Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe died sometime before June 25, 1813. She was approximately 50 years old. The burial record from Ste-Madeleine-de-Rigaud preserves her identity one final time:

"Le vingt cinq Juin, Mil huit cent treize... le corps de Marie Josette Sauvagesse de nation... agée de cinquante ans environs, Epouse Legitime de Gabriel Guilbeaultt Maçon Résident en la Seigneurie d'Argenteuil..."

— Ste-Madeleine-de-Rigaud, Burial Register, June 25, 1813She received the sacraments of the Church—"Munie des Secours de l'Eglise"—and was buried in the parish cemetery. Present at her burial were her son Gabriel Jr. ("Marie de la Defunte"), Ignace Poirrault père, and François Beaudry.

Even in death, her Indigenous identity was maintained: "Marie Josette Sauvagesse de nation." Eighty years later, an 1893 notarial document would still identify her the same way—her Indigenous heritage preserved in legal records across nearly a century.

A Second Chapter: Josette Closier

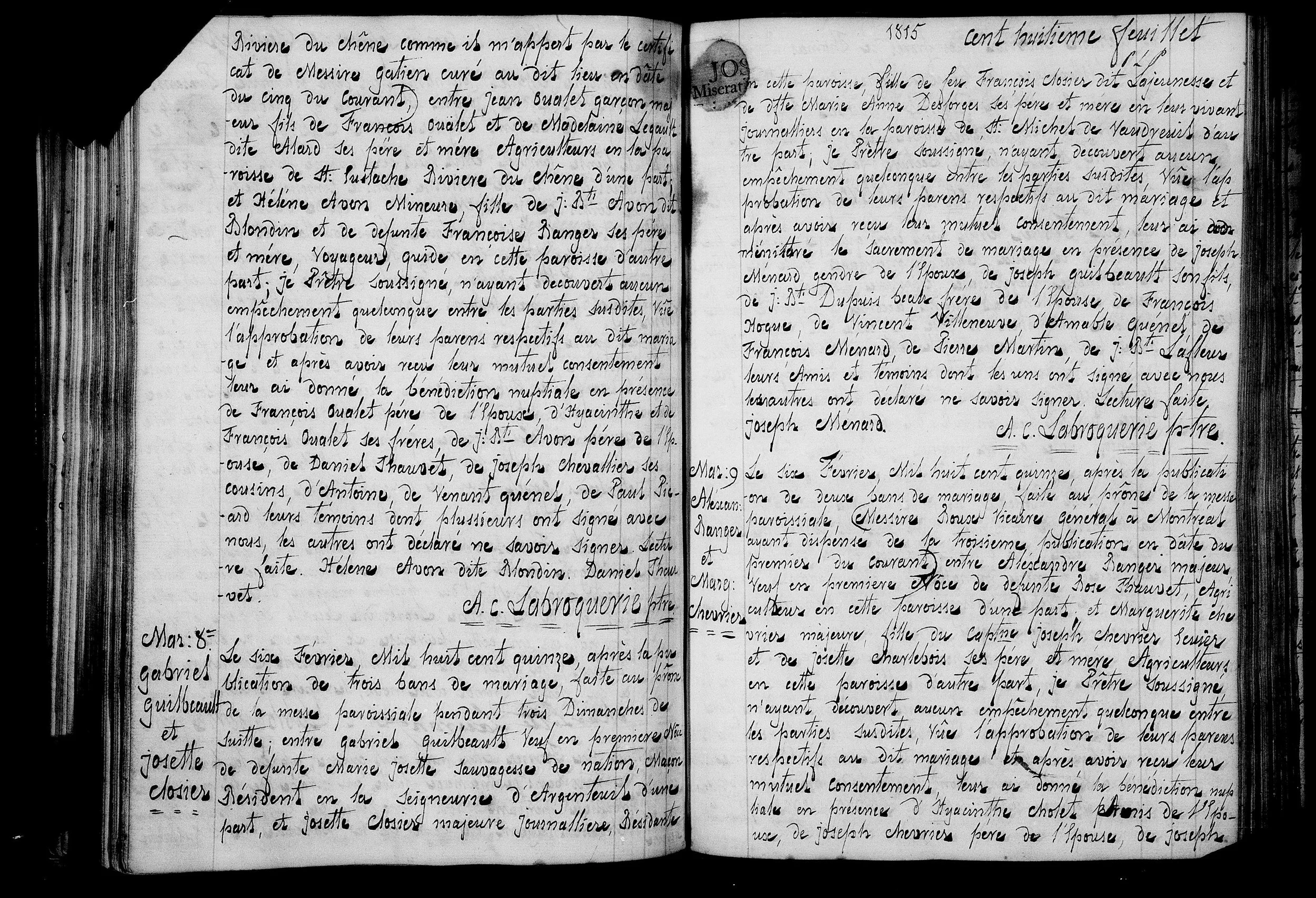

Less than two years after Marie Josephte's death, Gabriel remarried. On February 6, 1815, at Ste-Madeleine-de-Rigaud, he wed Josette Clausier dit Lapensée, daughter of François Clausier and Marie Anne Desforges St-Maurice.

The marriage record is significant for what it tells us about Marie Josephte: Gabriel is identified as "veuf en première noce de defunte Marie Josette Sauvagesse de nation, Maçon Résident en la Seigneurie d'Argenteuil." Even in his second marriage, his first wife's Indigenous identity is preserved.

Two Families, One Legacy

First Marriage: Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe

- Union began ~1789-1790

- Catholic marriage: 1801

- 7 children (5 survived infancy)

- Métis heritage documented

- Marriage lasted ~23 years

Second Marriage: Josette Closier

- Married February 6, 1815

- French-Canadian heritage

- 7 children (4 survived infancy)

- Marriage lasted ~18 years

- Gabriel was 53 at marriage

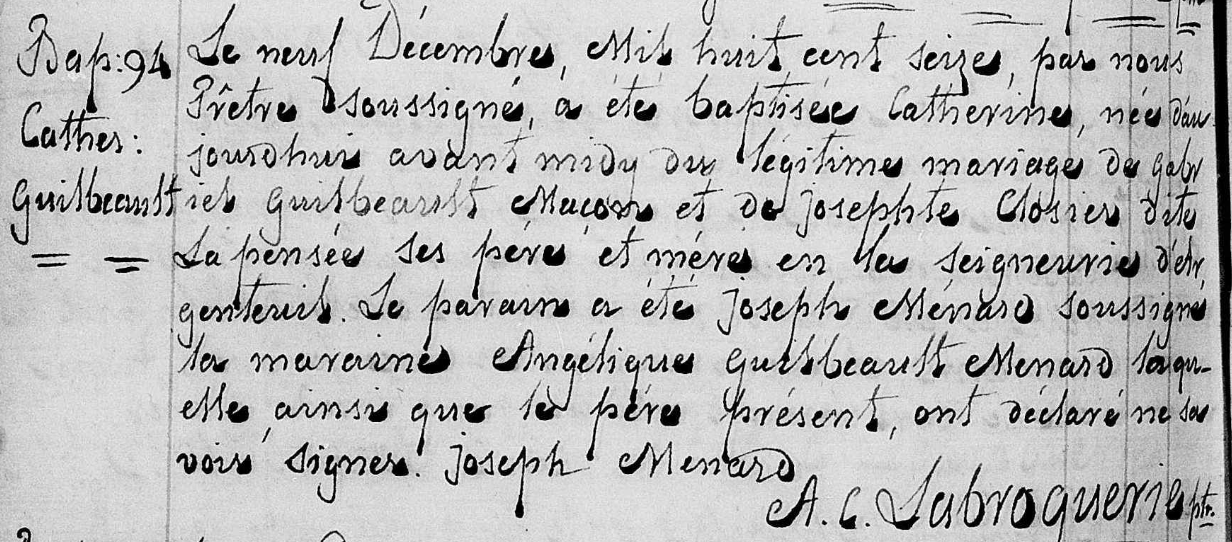

A touching detail connects the two families: when Gabriel and Josette's daughter Catherine was baptized in December 1816, the godmother was Angélique Guilbeault Menard—Gabriel's daughter from his first marriage. Marie Josephte's daughter stood as godmother to her half-sister, bridging the two families.

Sadly, little Catherine lived only six weeks, dying in January 1817. She would be one of three children from the second marriage who did not survive infancy.

Landowner on the Ottawa River

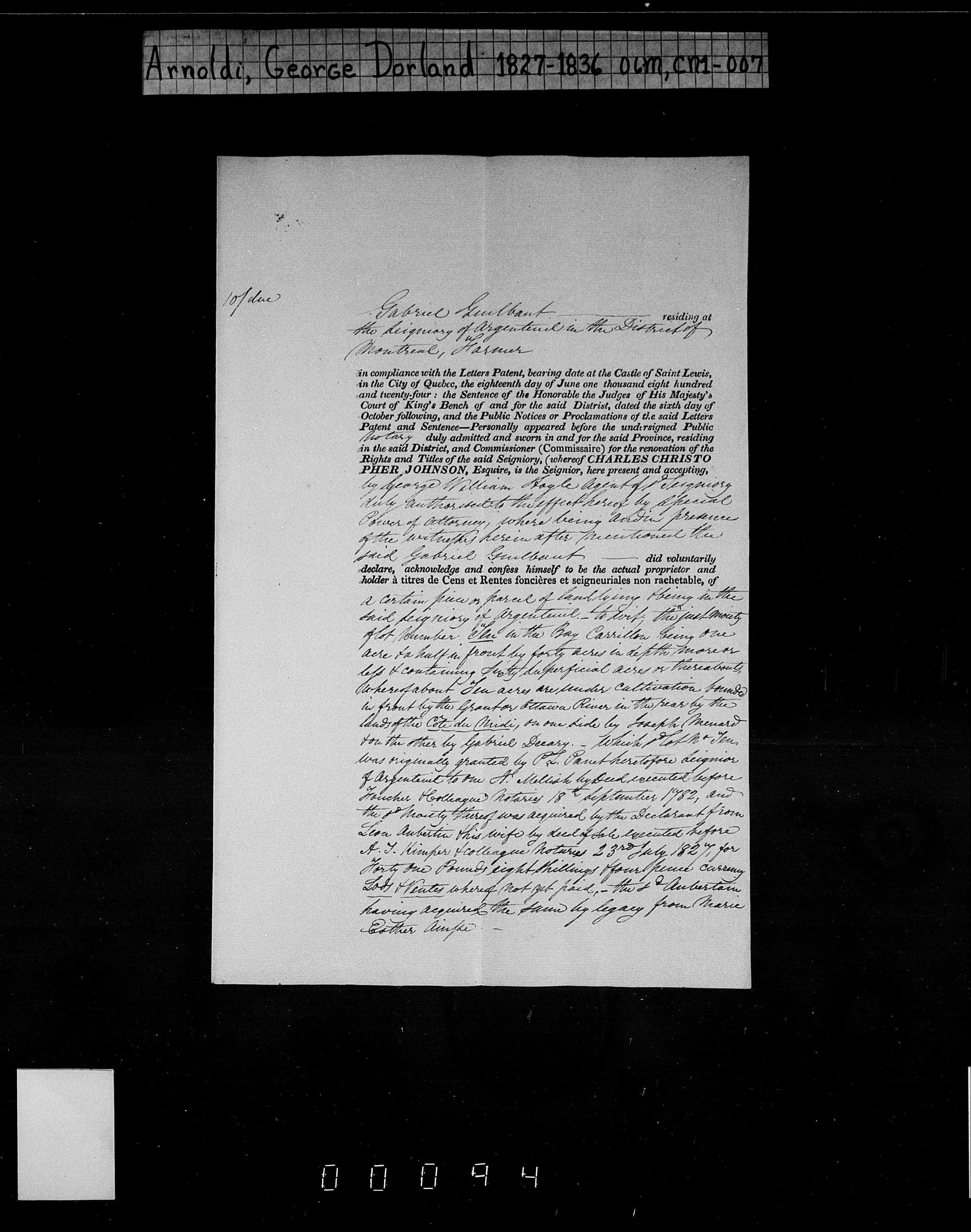

On July 30, 1827, Gabriel Guilbault completed a transformation that had begun decades earlier when he first set down his paddle. A notarial record from the Arnoldi collection documents his purchase of land in the Seigneury of Argenteuil—68 acres along the Ottawa River.

The document reveals the property details:

- Size: 2 arpents frontage × 40 arpents depth (approximately 68 acres or 27 hectares)

- Cultivated: About 10 acres cleared and farmed

- Location: South shore of the Ottawa River, Côte du Midi

- Neighbors: Joseph Ménard (one side), Gabriel Décary (other side)

- Purchase Price: £41, 8s, 4d (provincial currency)

- Chain of Title: Originally granted 1782, passed through several owners before Gabriel

The long, narrow lot was typical of the seigneurial system: river access at the front for transportation and water, with the property stretching nearly 2.5 kilometers inland. Gabriel's neighbor Joseph Ménard was almost certainly related to his son-in-law—Angélique had married Joseph Menard in 1815.

Final Years: St-Benoît, 1833

Gabriel Guilbault died on April 8, 1833, at approximately 70 years of age. He was buried in the parish cemetery of St-Benoît (now part of Mirabel, Quebec). His death record identifies him by his final occupation and residence—the mason of Argenteuil who had once paddled canoes to Lake Superior.

He had outlived his first wife by twenty years, his daughter Angélique by fourteen years, and several of his children. He left behind a family that spanned two cultures and would continue to carry forward the legacy of Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe.

Gabriel Guilbault's 71 years encompassed the fall of New France, the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the early stirrings of rebellion in Lower Canada. He had been a voyageur when canoes still ruled the waterways, and he died as railways were beginning to transform the landscape. Through it all, the documents he left behind preserved something precious: the identity of an Ojibwe woman whose descendants would one day search for her name.

Document Gallery

Continue the Journey

Gabriel Guilbault's story is part of a larger narrative—the transformation of Indigenous women from nameless "Sauvagesses" in colonial records to documented matriarchs whose descendants can now trace their heritage with confidence.

His wife Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe stands as one of the best-documented Indigenous women in Quebec parish records. The methodology that recovered her name—FamilySearch Full Text Search, systematic parish-by-parish investigation, and linguistic analysis of Ojibwe name patterns—offers a model for other researchers seeking their Indigenous ancestors.

Research Note: This episode documents Gabriel Guilbault père, the original voyageur. His son Gabriel Jr. (Episode 4) and grandson (Episode 5) continued the family line, eventually connecting to the Métis communities of the Ottawa Valley. Each generation carried forward Marie Josephte's legacy—documented in parish records, remembered in family stories, and now recovered through modern genealogical research.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY