The Guilbault Line: Pierre Guilbault

Pierre Guilbault

Where It All Began

Every family line has a beginning. For the Guilbaults of New France—whose descendants would include habitants, Quebec patriots, voyageurs who married into Ojibwe families, and eventually a million people living today—that beginning was a young man from La Rochelle who crossed the Atlantic with nothing but a power of attorney and the ambition to start over.

Pierre Guilbault arrived in New France in the summer of 1657. Over the next forty years, he would fail twice to secure a bride, finally marry a Fille du Roi who was older than most and more desperate than she let on, build one of Charlesbourg's most prosperous farms, survive a marital separation that scandalized the parish, and die nine months after his own children took him to court in a battle so bitter that the judge used the word "aversion" to describe their mutual hatred.

His story is not one of unbroken triumph. It is the story of how families are actually made: through failure and persistence, through crisis and reconciliation, through love and resentment that sometimes existed in the same household at the same time.

Pierre Guilbault (this episode) → Joseph Olivier Guilbault (1672-1739) →

Charles François Guilbault (Episode 5) → Charles Gabriel Guilbault (Episode 4) →

Gabriel Guilbault "le voyageur" (Episode 3) who married Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe

Origins: La Rochelle

Pierre Guilbault was born around 1647 in La Rochelle, on the Atlantic coast of France. His parents were François Guilbault and Marie Pignon, members of the parish of Saint-Barthélemy. The distinguished genealogist Father Archange Godbout searched extensively for Pierre's baptismal record but was unable to locate it—a common frustration for researchers working with 17th-century French records.

What we do know comes from later documents. Pierre claimed the parish of Saint-Barthélemy as his home. He was one of at least three children; his siblings Marie and Jean (baptized August 26, 1636) are documented in the La Rochelle registers.

La Rochelle was one of France's great Atlantic ports, the departure point for thousands of settlers bound for New France. The city's maritime economy shaped the opportunities available to young men like Pierre, who would have grown up watching ships sail west toward the colonies that promised land, freedom, and a fresh start.

The Young Attorney

On March 12, 1657, a notarial deed initialed by the notary Juppin in La Rochelle reveals Pierre Guilbault's first documented activity: he was serving as an attorney for Jacques Barbeau, a creditor seeking to collect 110 livres, 10 sols from one André Gullin, a pottery merchant who had fled to New France. Pierre was given full power to collect the debt, with permission to keep one-third as his fee.

This power of attorney was later registered in Guillaume Audouart's minutier in Quebec—proof that Pierre followed his commission across the Atlantic. By the summer of 1657, Pierre Guilbault had arrived in Canada.

The conclusion is obvious: this Pierre Guilbault came to the Colony in the summer of 1657. Moreover, in an act of the Sovereign Council dated October 17, 1663, Jean Le Royer, a merchant from La Rochelle passing through Quebec, asks Mathurin Roy on behalf of Pierre Guilbault to pay 300 livres owed since October 13, 1658—so much proof that Pierre had been in the country since 1657.

— Research notesOn March 23, 1664, Pierre appeared before Bishop François de Laval for a solemn confirmation ceremony. The zealous bishop had gathered 103 confirmands; Pierre, listed at age 23, occupied the 82nd place between the parishioner Clément Ruel and the Percheron Louis Desmoulins. Pierre was becoming established in his new world.

Two Failed Attempts

By 1665, Pierre was ready to marry. He was in his early twenties, established in the colony, and looking to start a family. But the path to matrimony proved unexpectedly difficult.

Pierre's Marriage Attempts Before Louise

What was wrong with Pierre Guilbault? The documents don't say. Perhaps he was poor. Perhaps he was difficult. Perhaps he simply lacked the charm that helped other bachelors secure brides in a colony where women were precious and marriages were often arranged within days of meeting.

Whatever the reason, by the summer of 1667, Pierre had been publicly rejected twice. He must have felt, as one historian noted, "a little humiliated."

September 1667: The St. Louis de Dieppe

On September 25, 1667, a ship dropped anchor at Quebec. The St. Louis de Dieppe had departed from Normandy on June 10, stopped at La Rochelle, and spent 107 brutal days crossing the Atlantic. Aboard were ninety Filles du Roi—young women sponsored by King Louis XIV to populate his colony—along with a hundred engagés (contract workers), fifteen horses, and crew.

Among the passengers was Louise Senécal.

Louise was different from the other Filles du Roi. At 30 years old, she was six years older than the average bride. She had waited 22 years after her mother's death to make this desperate gamble. Twenty women aboard the ship had filed a formal complaint about conditions before departure; Louise's name wasn't among them. She boarded anyway.

Five days after arriving, Louise appeared before notary Pierre Duquet with Pierre Guilbault—the man who had failed twice to marry. The contract they signed on September 30, 1667, specified a dowry of 100 livres—double the standard amount for Filles du Roi.

October 6, 1667: The Wedding

On a Friday morning, eleven days after Louise stepped off the St. Louis de Dieppe, she and Pierre appeared before the priest Henri de Bernières at Notre-Dame-de-Québec. Pierre Chamard and Pierre Coirier stood as witnesses. The marriage record lists Louise's age as 24—though she was actually 30. Whether this was a strategic lie or a clerical error, the documents don't say.

Neither bride nor groom could sign their names.

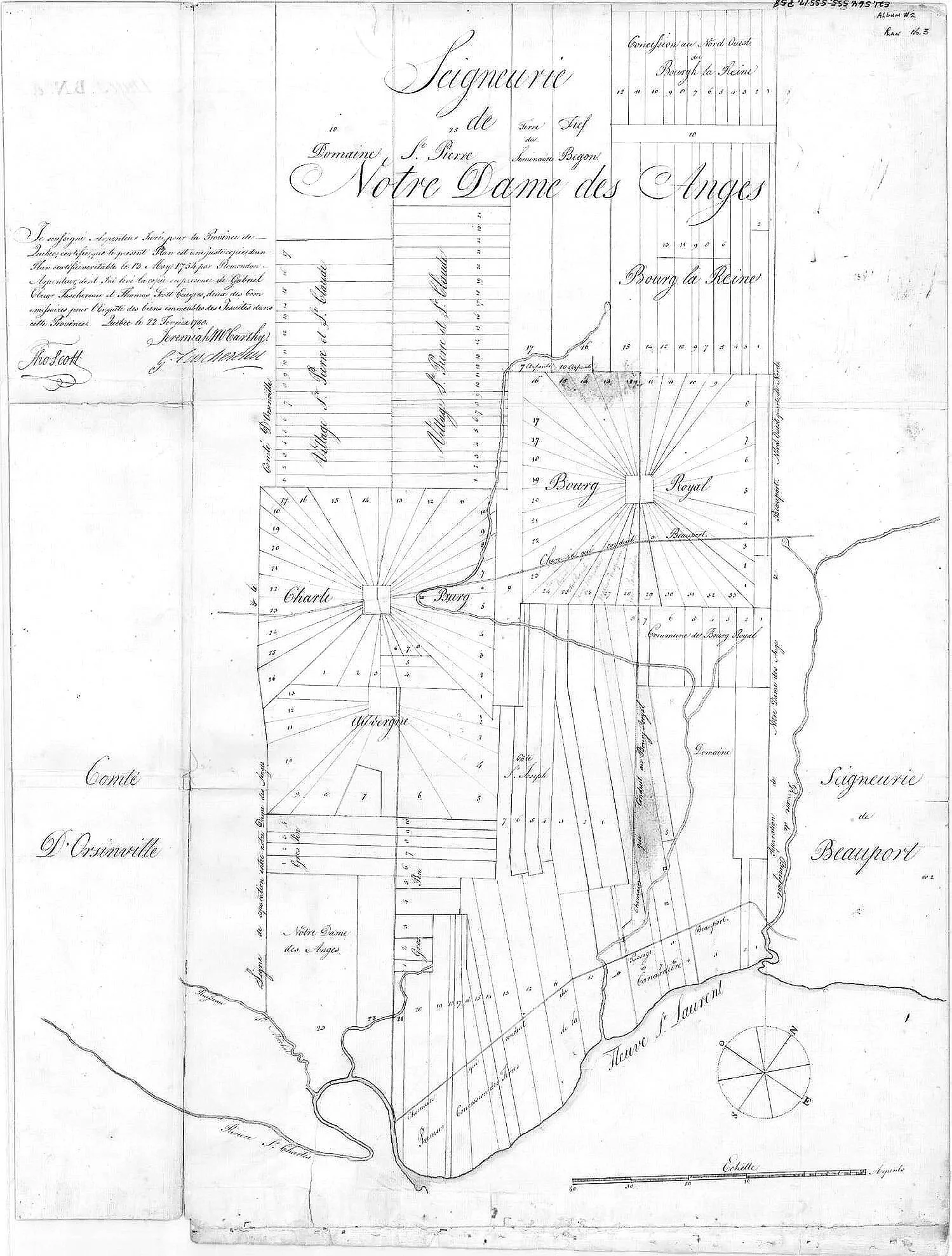

That same day—possibly within hours of the ceremony—census takers arrived at their door. The 1667 census records: Pierre Guillebaud, 26; Louise Senécal, 24; 2 arpents under cultivation. From this modest beginning at Côte de Notre-Dame-des-Anges, they would build something remarkable.

Building Charlesbourg: 1667-1681

From two arpents to thirty. From one dwelling to a prosperous farm with cattle and horses. The transformation took fourteen years of relentless work.

Pierre and Louise moved to Charlesbourg, in the village of Petite Auvergne, where they received a land grant—probably an oral concession from the Jesuit fathers. Their neighbors were Jean Lemarché (known as Laroche) and Pierre Lefebvre. Over the following years, Pierre cleared forest, built fences, constructed buildings, and expanded their cultivated acreage.

He also took on side work. On December 27, 1676, he contracted to cut, split, and prepare 24 cords of firewood for Jean Giroux, a master tailor. In October 1679, he signed a three-year farm lease with Olivier Morel, Sieur de La Durantaye, to cultivate two farms "at half gain, fruits and income." Pierre was not afraid of work or risk.

The 1681 Census: Success

By 1681, the census recorded a transformed household:

Of the 96 horses in all of New France, Pierre owned two. By frontier standards, they had succeeded.

The Children of Pierre and Louise

Pierre and Louise raised four children to adulthood—a modest family by 17th-century standards, but one that would have an outsized impact on Quebec genealogy.

| Child | Born | Married | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marie | September 13, 1668 | François Dubois, 1688 | 8 children; widow and tavern keeper in Quebec by 1744 |

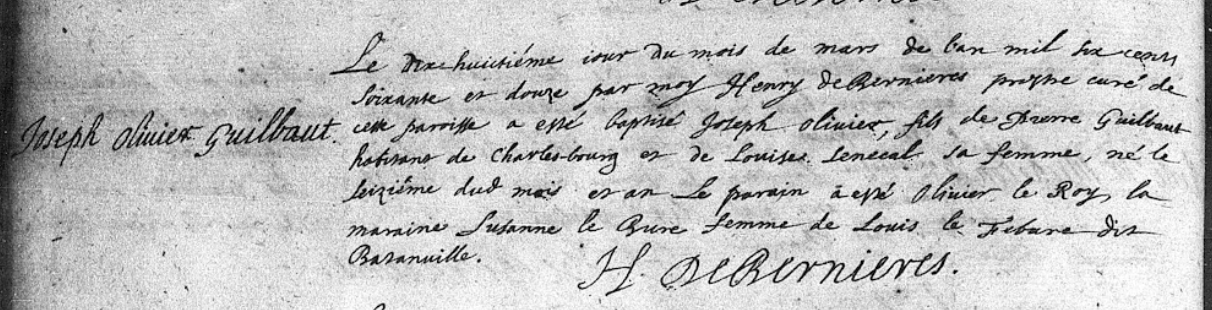

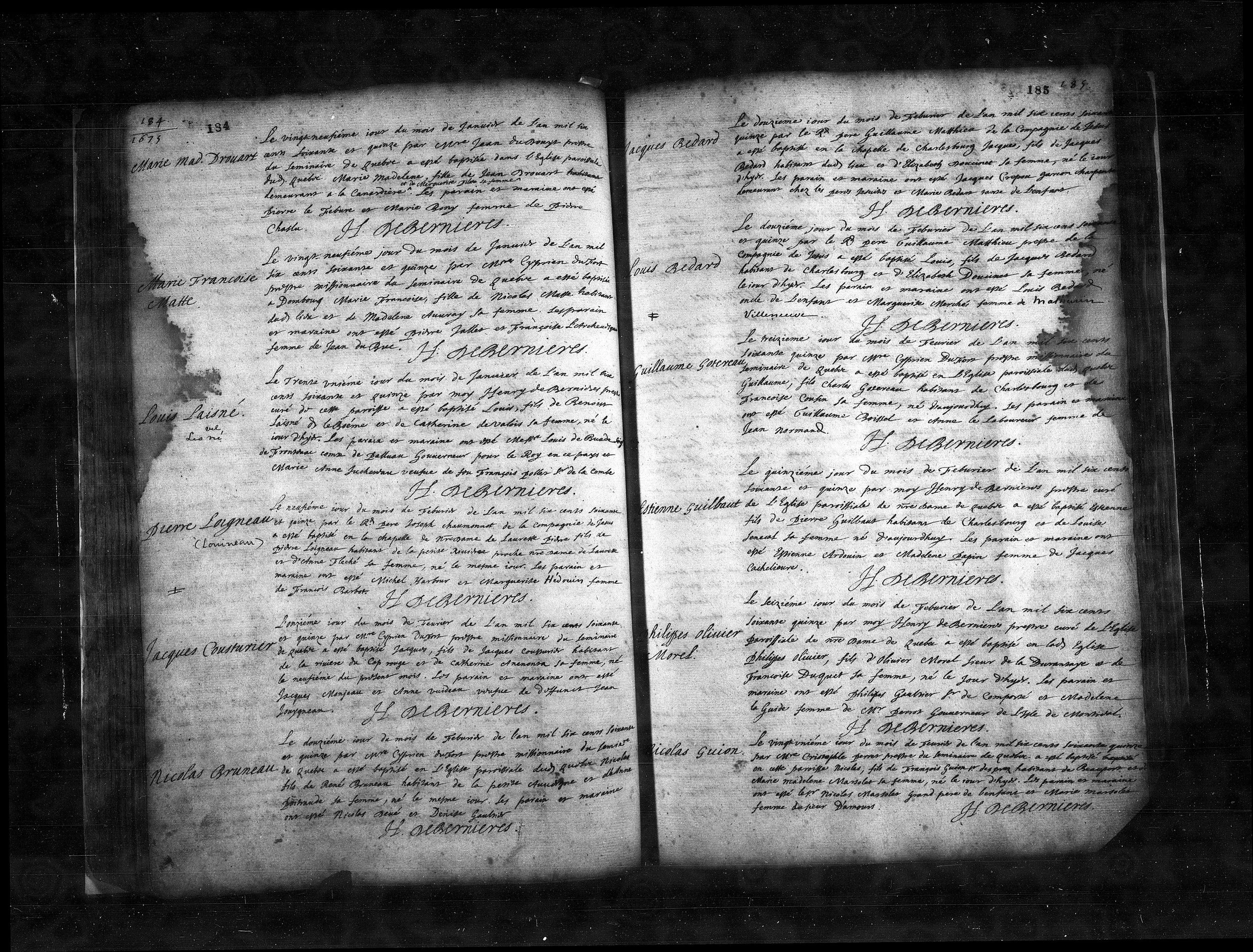

| Joseph-Olivier | March 18, 1672 | Marie-Anne Pajot, 1694 | Direct ancestor to Gabriel the voyageur (Episode 3) |

| Étienne | February 15, 1675 | Françoise Roy, 1699 | 9 children; died age 27 at Hôtel-Dieu |

| Elisabeth | December 17, 1679 | — | Disappeared from records after 1681; fate unknown |

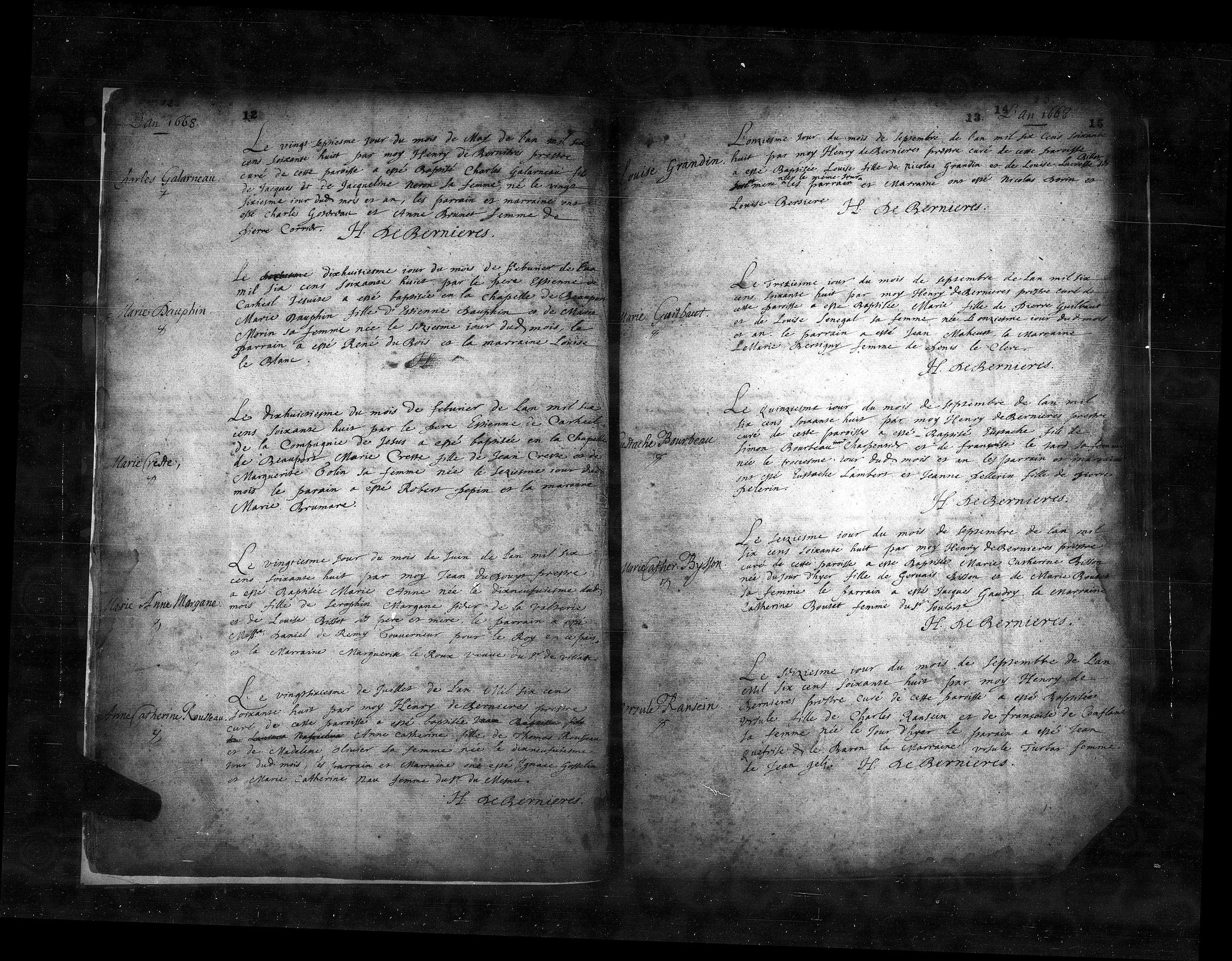

The Baptismal Records

December 1679: The Separation

On December 17, 1679, the Abbé Charles Glandeet baptized Elisabeth Guilbault in Charlesbourg. The record contains an extraordinary statement: Louise was "not living with Pierre but that he was the father."

This public declaration of marital separation—recorded in the parish register for all to see—defied every social norm of 17th-century New France. Married couples did not live apart. The church did not sanction separation except in extreme circumstances. Yet here was Louise Senécal, publicly stating that she had left her husband while still acknowledging him as the father of her newborn child.

What happened? The documents are silent. We know only that by the 1681 census, Pierre and Louise were living together again, with their four children and their substantial property. They had reconciled—or at least, they had found a way to continue their partnership.

Elisabeth herself disappears from the records after the 1681 census. She was no longer there by April 13, 1693, when Louise died. Her fate remains one of the family's unsolved mysteries.

April 13, 1693: Louise Dies

Louise Senécal died on April 13, 1693, at approximately age 56. Her death certificate was either not recorded in the parish registers or has been lost—but the date is confirmed by subsequent legal documents.

What happened next would define the final years of Pierre's life and the relationship with his children.

On the same day Louise died—April 13, 1693—Pierre appeared before notary Louis Chambalon to sign a marriage contract with Jeanne Morin, a 20-year-old woman. Present as witnesses: his own daughter Marie and son-in-law François Dubois.

The same-day timing—documented in colonial records—reveals either shocking insensitivity or desperation. Perhaps Pierre needed someone to run the household. Perhaps the contract had been prepared in advance. Perhaps Louise's death was expected and Pierre had made arrangements. Whatever the reason, his children would never forget it.

The contract with Jeanne Morin was eventually annulled. On August 6, 1694, Jeanne married Alexandre Biron instead.

For nearly four years, Pierre kept Louise's estate unsettled. Despite court orders, despite his children's demands for their mother's share of the community property, he refused to divide what they had built together over 26 years.

January 1697: The Children Strike

By late 1696, Pierre was courting again—this time Françoise LeBlanc, a 22-year-old from a respectable Charlesbourg family. His children—Marie (now 28, married to François Dubois for eight years), Joseph (24, married to Marie Anne Pajot for two years), and Étienne (21, still legally a minor)—realized they had to act before their mother's legacy was absorbed into a new marriage.

What followed was a strategic legal campaign that would culminate in one of the most extraordinary court orders in 17th-century Quebec records.

The 1697 Timeline

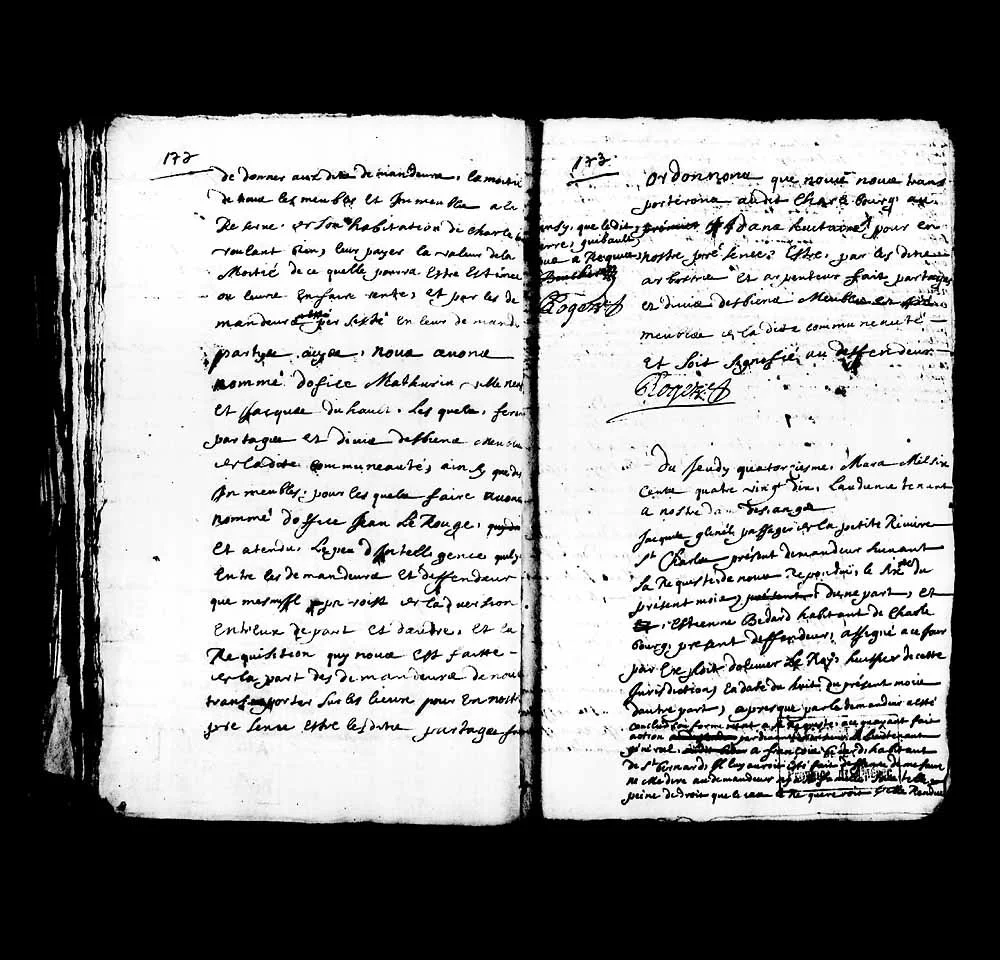

February 28, 1697: "Considérant l'aversion..."

On February 28, 1697, Provost Judge Guillaume Roger issued an order unlike anything in the typical colonial record. The language he used would preserve this family conflict for centuries:

"Considérant l'aversion entre les demandeurs et défendeur..."

"Considering the aversion between the plaintiffs and defendant..."

— BAnQ (03Q,TL5,D2769-119), "Ordonnance...nomination d'arbitres"Aversion. Mutual repulsion. Hostility so severe that the court acknowledged it couldn't proceed normally.

The judge ordered extraordinary measures:

- He would personally travel to Pierre's home in Charlesbourg

- Three arbitrators were appointed: Mathurin Villeneuve and Jacques Duhaut for moveable property, Jean Lerouge for immoveable property (land)

- The court would supervise the property division—an almost unheard-of intervention

Courts didn't make house calls. Judges didn't personally supervise estate divisions. But the hatred between Pierre and his children was so palpable, so public, so disruptive that normal procedures couldn't contain it.

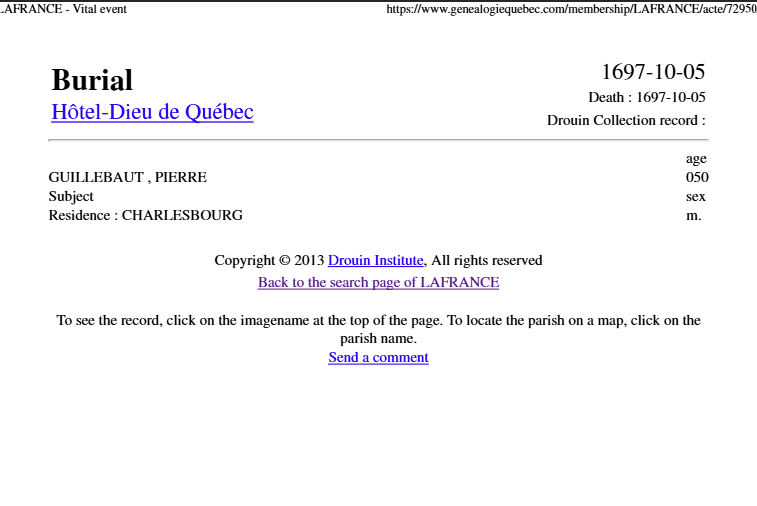

October 5, 1697: Death at Hôtel-Dieu

Nine months after the Aversion Order, Pierre Guilbault died at the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec. He was approximately 50 years old. His marriage to Françoise LeBlanc had produced no children.

The burial record is brief: Guillebaut, Pierre. Residence: Charlesbourg. Age: 50. Sex: m.

Did the stress of the family war contribute to his death? Did he die reconciled with his children or still estranged? The documents are silent. What we know is that his children—Marie, Joseph, and Étienne—survived him, inherited what remained, and went on to raise families of their own.

Joseph Olivier Guilbault, the second child, married Marie Anne Pajot in 1694 and settled in Charlesbourg. Their son Charles François—born October 30, 1702—would become the habitant featured of Episode 5. And Charles François's son Gabriel would father the voyageur who married Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe.

The line continued.

The Founder's Legacy

Pierre Guilbault was not a hero. He failed twice to marry before finding Louise. He may have driven her away in 1679. He tried to remarry on the day she died. He refused to settle her estate for nearly four years, forcing his own children to take him to court in a battle so bitter that the judge had to personally intervene.

And yet.

He crossed an ocean with nothing but a power of attorney. He cleared forest and built a farm from wilderness. He raised four children to adulthood in a colony where survival was never guaranteed. He accumulated property that required three arbitrators and a Provost Judge to divide. Whatever his faults, he built something substantial enough to fight over.

The fight itself became Louise's monument—preserved in the judicial record as evidence that she built something worth fighting for, and raised children determined enough to ensure their mother's work would not be forgotten.

By 1729, Louise and Pierre had 61 documented descendants. Genealogist Peter J. Gagné estimates they left approximately one million descendants to the present day—including the voyageur Gabriel Guilbault and everyone who descends from his marriage to Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe.

Pierre Guilbault (~1647-1697) & Louise Senécal (1637-1693)

↓

Joseph Olivier Guilbault (1672-1739) & Marie Anne Pajot

↓

Charles François Guilbault (1702-1760) - The Habitant (Episode 5)

↓

Charles Gabriel Guilbault (1731-1784) - The Quebec Patriarch (Episode 4)

↓

Gabriel Guilbault (1762-1833) - The Voyageur (Episode 3)

married Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe (Ojibwe)

Continue the Story

The full story of Pierre Guilbault and Louise Senécal—including the complete court documents, the voyage of the St. Louis de Dieppe, and the methodology used to reconstruct their lives—is available in the Louise Senécal Guilbault case study and three-part blog series.

Louise Senécal Guilbault: Case Study

From Orphan to Founding Mother: A Journey in Three Acts

View Case StudyDocument Gallery

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY