The Seven Fires: Understanding Marie Josephte’s Ojibwe Heritage

The Seven Fires

Before French traders arrived at the St. Mary's Rapids, before the fur trade reshaped the Great Lakes, Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe's ancestors had already completed a 500-year journey guided by prophecy—from the Atlantic coast to the land where food grows on water.

When Father Leclerc recorded Marie Josephte as "de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur" in 1801, he was documenting far more than a tribal affiliation. He was naming a woman whose people—the Baawitigowininiwag, the People of the Rapids—had followed sacred prophecy westward for centuries, stopping at last at the very place where she would meet Gabriel Guilbault. To understand who she was, we must understand where her people came from.

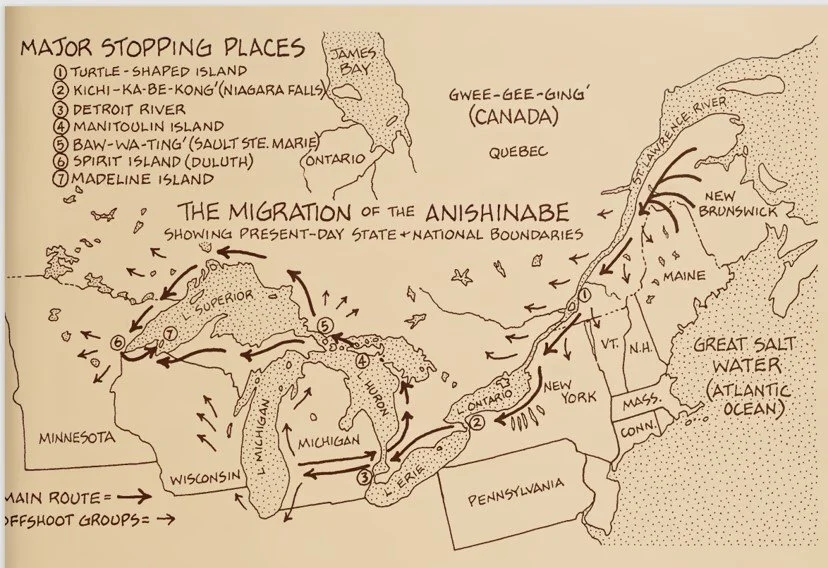

The Migration of the Anishinabe: From the "Great Salt Water in the East" (Atlantic Ocean) to the Great Lakes, following the Seven Fires Prophecy through seven major stopping places over approximately 500 years.

The Seven Fires Prophecy

According to Ojibwe oral tradition preserved in the Midewiwin Lodge, seven prophets came to the Anishinaabe people when they lived on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean. Each prophet foretold an era—a "fire"—that would shape their future. The first prophet delivered a warning: "If you do not move, you will be destroyed." And so began a migration that would take 500 years to complete.

Much of what we know about the Ojibwe migration comes from The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway by Edward Benton-Banai, an Ojibwe elder and teacher who compiled traditional teachings from elders and the Midewiwin Lodge. This work, along with birchbark scrolls like the one created by Eshkwaykeeshik (James Red Sky), preserves the oral history that guided the Anishinaabe people westward.

The Seven Fires

The First Fire: The Journey Begins

The first prophet told the people they must move west or face destruction. They were instructed to follow the Sacred Megis Shell to a turtle-shaped island—the first of seven stopping places on their migration.

The Second Fire: Lost Direction

The second prophet warned of a time when the direction of the sacred shell would be lost. But a boy would be born to guide the people back to their traditional ways.

The Third Fire: The Chosen Land

The third prophet foretold that the people would find their chosen land in the west, where "food grows on water"—a reference to manoomin, wild rice, which would sustain the people in their new homeland.

The Fourth Fire: The Light-Skinned Race

The fourth prophet predicted the arrival of Europeans and offered two possible outcomes: a path of brotherhood leading to a mighty nation, or a "face of death" and destruction. History would prove which path was taken.

The Fifth Fire: False Promise

The fifth prophet warned of a time of great struggle, when a false promise of salvation would nearly destroy the people's traditional knowledge and way of life.

The Sixth Fire: Loss of Elders

The sixth prophet foretold that children would be taken from their elders, leading to a devastating loss of language, culture, and purpose—a prophecy that residential schools would fulfill.

The Seventh Fire: Rebirth

The seventh prophet spoke of a "New People" who would retrace their ancestors' steps to reclaim lost wisdom, eventually lighting an eternal "Eighth Fire" of peace, unity, and renewal.

Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe was born during the Fourth Fire—the era of contact with Europeans. Her marriage to Gabriel Guilbault, a French-Canadian voyageur, embodied the crossroads that prophecy had foretold: two peoples meeting, their futures intertwined.

The Great Migration

The Anishinaabe migration began around 900 CE and took approximately 500 years to complete. Following waterways and the guidance of the Sacred Megis Shell, the people traveled from the Atlantic coast through the St. Lawrence River system to the Great Lakes, stopping at seven sacred places along the way.

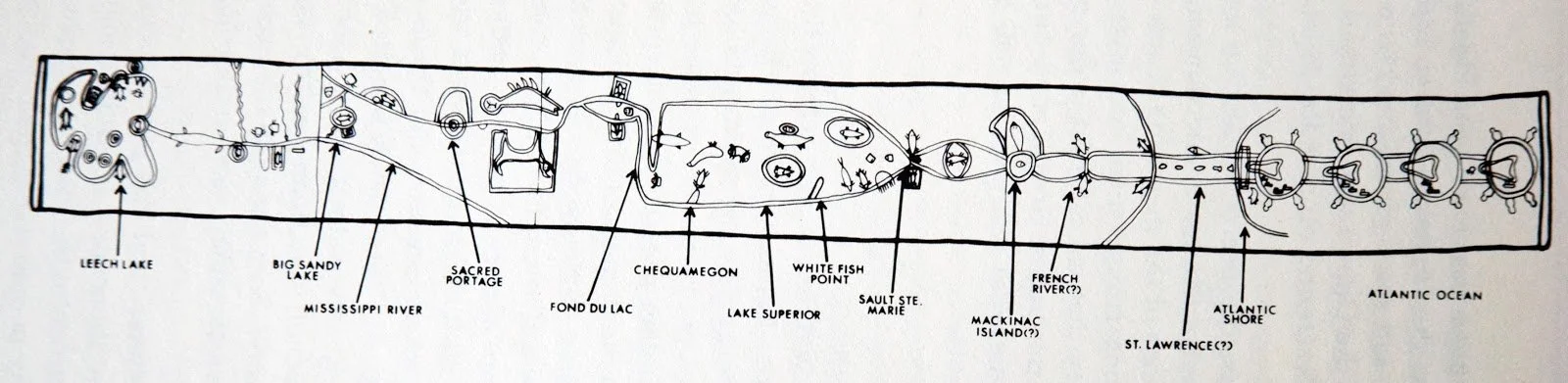

A wiigwaasabak (birchbark scroll) created by Eshkwaykeeshik (James Red Sky), recording the Ojibwe migration from the Atlantic shore through Sault Ste. Marie to Leech Lake. These scrolls were used ceremonially by Midewiwin medicine keepers to preserve sacred knowledge across generations.

"Boozhoo, I am going to try to reconstruct the chi-bi-moo-day-win' (migration) of my Ojibway ancestors. I will draw upon the words given to us by the prophets of the Seven Fires. I have also looked at old maps of North America that might give hints to places referred to by the seven prophets and by my grandfathers."

A geographical interpretation of Red Sky's birchbark chart, mapping the symbolic representations to actual Great Lakes geography. The chart moves from the Atlantic shore (right) through Sault Ste. Marie to Leech Lake (left), recording the entire 500-year migration.

The Council of Three Fires

During the migration, the Anishinaabe people divided into three distinct but allied nations. Around 796 CE, at Michilimackinac (the Straits of Mackinac), they formalized their relationship as the Council of Three Fires—Niswi-mishkodewinan—an alliance that would endure for over a thousand years.

The Three Fires Confederacy

Ojibwe

Odawa

Potawatomi

The Council managed relations with other Indigenous nations and later with European powers. They fought together during the Beaver Wars against the Iroquois Confederacy, allied with the French during the French and Indian War, and with the British during the War of 1812. Marie Josephte was born into this world of alliance and diplomacy—a world where her people stood at the center of Great Lakes politics and trade.

Baawitigong—the Place of the Rapids—was known as the gathering place of the Three Fires Confederacy. Diverse tribes met here not only to harvest the abundant whitefish but to engage in politics, religious rituals, trade, and the strengthening of alliances. This is the world Marie Josephte knew, and the world Gabriel Guilbault entered when he arrived as a voyageur in the 1790s.

The Doodem: The Clan System

The doodem (clan) system was the foundation of Ojibwe social organization, governance, and identity. Derived from the word ode' meaning "heart," the term doodem signifies an extended family—"the expression of one's heart." Seven original clans provided the framework for society, each with specific responsibilities.

Clan membership was patrilineal—passed from father to child. Members of the same clan were considered direct family and forbidden from marrying one another. This rule of exogamy strengthened genetic diversity and created bonds between different families and communities across the entire Anishinaabe nation.

Marie Josephte's spirit name—Abitakijikokwe, "Half-Sky Woman"—carries celestial associations that might suggest a connection to the Bird Clan (spiritual leaders) or the Crane Clan (associated with the sky). However, clan identity was patrilineal, so her clan would have come from her father's line. Without additional documentation, her specific clan affiliation remains unknown—but understanding the clan system helps us understand the social world she inhabited.

Why This Matters

Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe was not simply an "Indigenous woman" who married a French trader. She was a member of the Ojibwe nation—the Keepers of the Faith—whose ancestors had followed prophecy across a continent. She belonged to the Council of Three Fires, a political and military alliance over a thousand years old. She came from Baawitigong, the sacred gathering place at the fifth stopping place of the great migration. Understanding this heritage transforms how we see her—not as a footnote in colonial history, but as a woman standing at the intersection of two worlds, both with deep roots.

Finding Your Clan Today

For descendants of fur trade families like the Guilbaults, understanding and potentially reclaiming Ojibwe clan identity requires navigating both genealogical research and traditional spiritual protocols. The disruptions of colonization—including residential schools—severed many families from this knowledge. But paths to recovery exist.

Two Paths to Clan Identity

The Paper Trail: Genealogical Research

Clan identity was sometimes recorded in Indian Census Rolls (1885–1940), treaty records where signers marked their clan totems, and some church and school records. Tribal enrollment offices may have archives mentioning ancestors' clan affiliations. Since clan membership is patrilineal, tracing the paternal line is essential.

The Spiritual Trail: Traditional Protocol

When paper records fail, traditional law states that your clan is "watching over you" even if you don't know its name. An Elder or spiritual leader with the gift of "dreaming" can seek this information through ceremony. The process begins by offering tobacco (semaa) and requesting guidance. If your clan is revealed, it may be formally announced at a Naming Ceremony.

Commercial DNA tests cannot identify your clan—they only provide broad ancestry. Clan identity is a social and spiritual designation, not a genetic one. In Anishinaabe tradition, you do not "choose" a clan based on preference; you are either born into one or have one revealed through ceremony. In some cases, if no identifiable clan exists, a teacher may formally adopt you into their clan so you have a place in the community.

For those wishing to explore this path, the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians Language & Culture Department (906-635-6510) and Garden River First Nation (705-946-6300) can provide guidance and connect you with cultural resources and Elders.

For Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe

Half-Sky Woman of the Saulteaux Nation, whose ancestors followed the Sacred Megis Shell from the Atlantic to Baawitigong—and whose descendants now follow the paper trail back to her.

The Guilbault Line Series

The Guilbault Line: A Documentary Biography →

The complete case study tracing the family from Quebec to the present.

Episode 3: Gabriel Guilbault — Le Voyageur →

Marie Josephte's husband and his 71-year journey through the fur trade.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY