The Carignan-Salières Regiment

Before the King's Daughters could cross the Atlantic, before the first concessions were cleared along the St. Lawrence, before New France could become anything more than a fragile experiment clinging to a riverbank — someone had to make it safe. In 1665, Louis XIV sent 1,200 professional soldiers to do exactly that. Among them were ten of our direct ancestors.

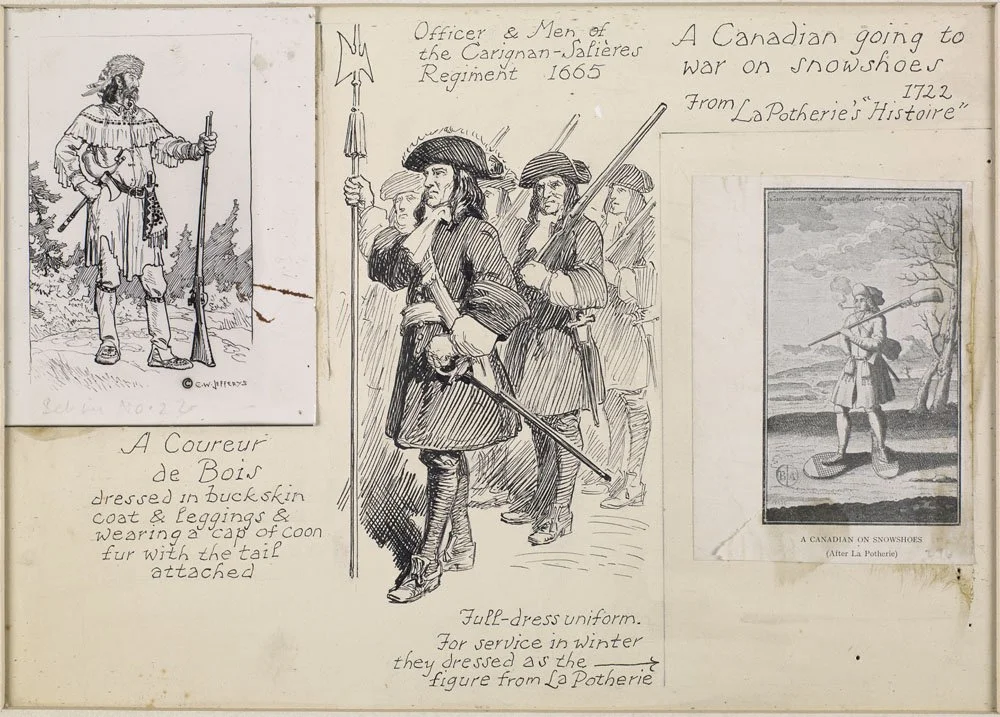

The arrival of the Carignan-Salières Regiment in New France, 1665.

The Carignan-Salières Regiment was no ordinary colonial militia. It was a professional military force — well trained, disciplined, and organized — something New France had never had before. Named for Colonel Thomas-François de Savoie, Prince de Carignan, and Henri de Chastelard, Marquis de Salières, the regiment comprised 24 companies and approximately 1,200 officers and soldiers. Their mission: defend the colony and suppress the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) raids that had brought New France to the edge of extinction.

Before their departure from France, in 1662, Jean-Baptiste Colbert had asked Pierre Boucher to submit a written report on Canada's resources. Upon his return, Boucher wrote his memoir entitled Histoire véritable et naturelle des moeurs et productions du pays de la Nouvelle France vulgairement dite le Canada, published in Paris in 1664. One of the positive effects of his embassy was the King's decision to send the regiment under the command of Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy.

The Crossing: La Rochelle to Quebec (1665)

Seven ships were required to transport the regiment to New France. The first, Le Vieux Siméon, a Dutch ship chartered by La Rochelle merchant Pierre Gaigneur, departed 19 April 1665 carrying the companies of La Fouille, Froment, Chambly, and Rougment. She arrived at Quebec on 1 July 1665.

Next came two royal vessels: La Paix and L'Aigle d'Or, departing La Rochelle on 13 May 1665. They carried the companies of La Colonelle, Contrecoeur, Maximy, Sorel, de Salières, La Fredière, Grandfontaine, and La Motte, arriving at Quebec on 18 August.

The final two royal ships — Le Saint Sébastien and Le Justice — departed La Rochelle on 24 May 1665. Aboard Le Saint Sébastien sailed the newly appointed Intendant of New France, Jean Talon, and Governor Daniel de Rémy de Courcelles. Aboard Le Justice were the companies of Du Prat, Naurois, Laubia, Saint-Ours, Petit, La Varenne, and Vernon. They arrived at Quebec on 12 September 1665.

Le buste de Pierre de Saint-Ours at Saint-Ours-sur-le-Richelieu. Unveiled 1922 by Elzéar Soucy; the likeness is probably imaginary.

Four additional companies arrived with Tracy himself from the Antilles aboard Le Brézé on 30 June 1665 — the captains La Durantaye, Berthier, La Brisardière, and Monteil. Tracy had been in the West Indies as part of his royal commission to establish Louis XIV's rule of the French colonies following the King's takeover after the bankruptcy of the Company of 100 Associates.

Among the soldiers aboard Le Justice was a young man from Picardy named François Séguin, serving in the Company of St-Ours under Captain Pierre de Saint-Ours. Born in October 1640 in Grenoble, Saint-Ours was a minor French noble who had been a cadet in the regiment since 1658 and received his captain's commission on 7 February 1665. He would become one of the military men who transitioned from officer to colonial seigneur — and the bond between him and his soldiers would endure across four decades.

A Chain of Forts Along the Richelieu (1665–1666)

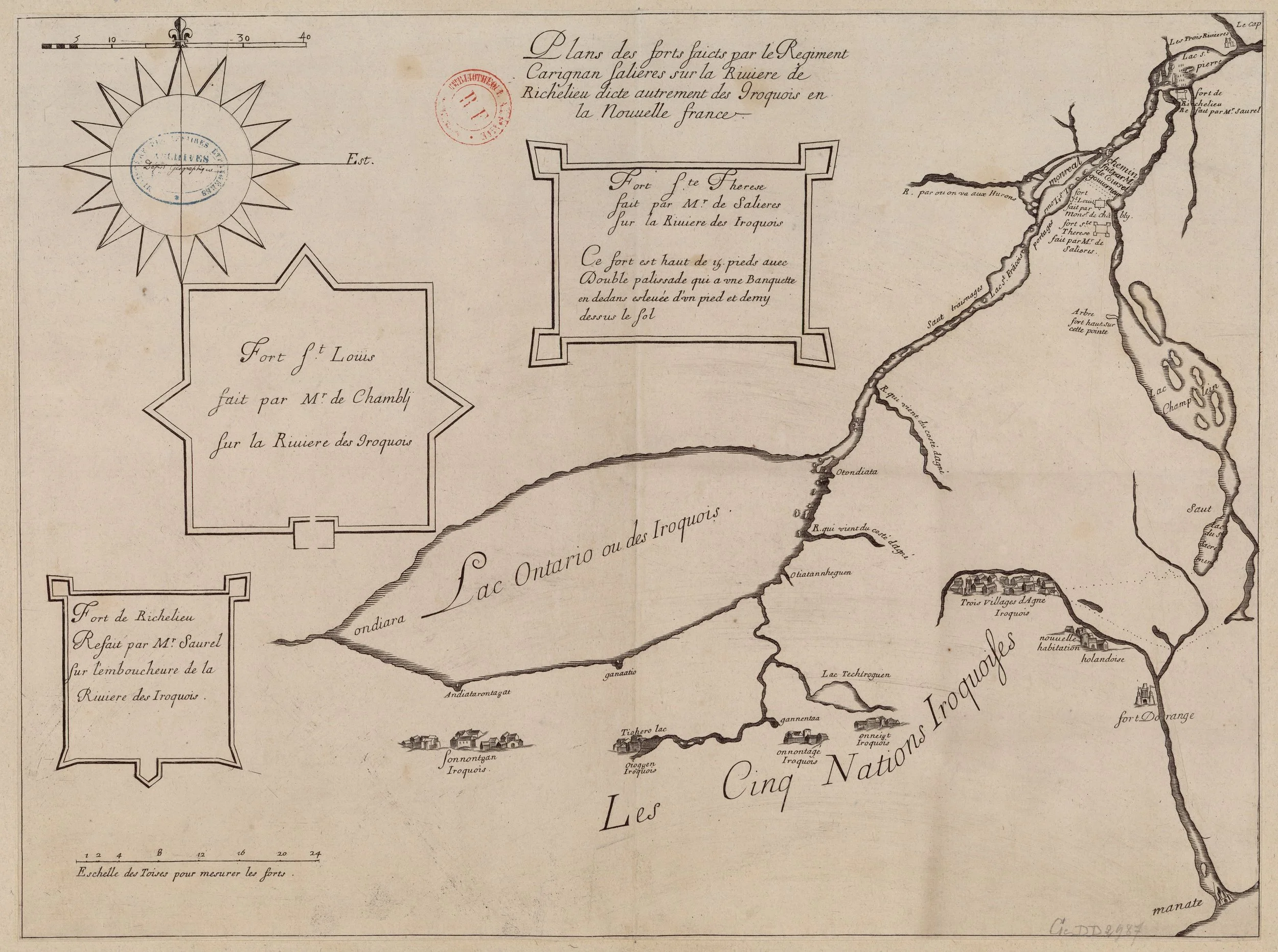

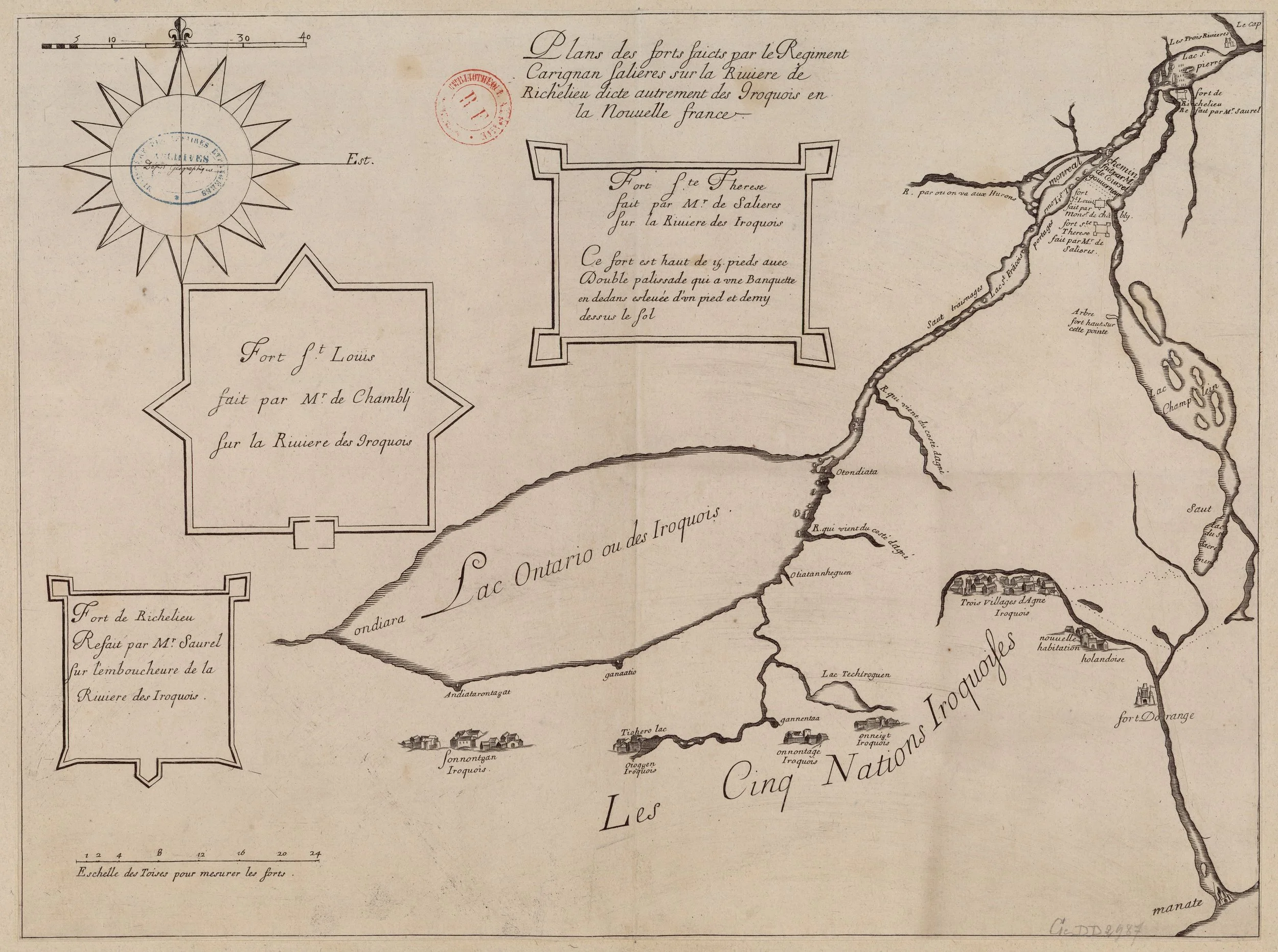

Plan des forts faicts par le Regiment Carignan Salières — the chain of forts along the Richelieu River.

The Richelieu River was the invasion corridor. Flowing north from Lake Champlain to the St. Lawrence, it was the route used by Iroquois war parties coming from present-day New York. The regiment's first task was to build a chain of forts to seal this corridor: Fort Richelieu at Sorel, Fort Chambly, Fort Sainte-Thérèse, and Fort Saint-Jean.

Company by company, the soldiers cleared land, felled trees, erected palisades, dug ditches, and built barracks. They stood watch along river crossings and conducted patrols between forts. This was grueling physical labor mixed with constant military readiness — and it was nothing like European warfare.

Unlike anything they had trained for in France, these soldiers had to adapt quickly to conditions that defeated many European troops: the brutal Canadian winter, cramped forts built of green wood, movement on snowshoes through deep snow, and woodland warfare against an enemy who knew every trail and waterway.

Fort Chambly: Heart of the Defense

Fort Chambly, 1840, by William Henry Bartlett. Originally built in wood by Captain Jacques de Chambly's company in 1665, rebuilt in stone 1709–1711.

Fort Chambly, originally built as a wooden palisade by Captain Jacques de Chambly's company in the autumn of 1665, was one of the most important positions on the Richelieu. It stood at the foot of the rapids on the Richelieu River — the point where canoes traveling south toward Lake Champlain had to portage, making it a natural chokepoint for any force moving through the corridor.

The fort served as a major garrison point for the regiment. Soldiers from multiple companies rotated through its walls, standing watch, maintaining the defenses, and conducting patrols south toward Fort Saint-Jean and beyond. Many soldiers formed close ties with settlers during this time — ties that would later lead to marriage and land grants.

Fort Chambly today — the only surviving fort of the Richelieu line. Now a National Historic Site, it stands on the same ground where Carignan-Salières soldiers garrisoned 360 years ago.

Fort Chambly is the only surviving fort from the Richelieu defensive line. Rebuilt in stone between 1709 and 1711, it stands today as a National Historic Site on the same ground where Carignan-Salières soldiers first hammered wooden stakes into the earth in 1665.

Fort Richelieu at Sorel: Where Our Soldier Wintered

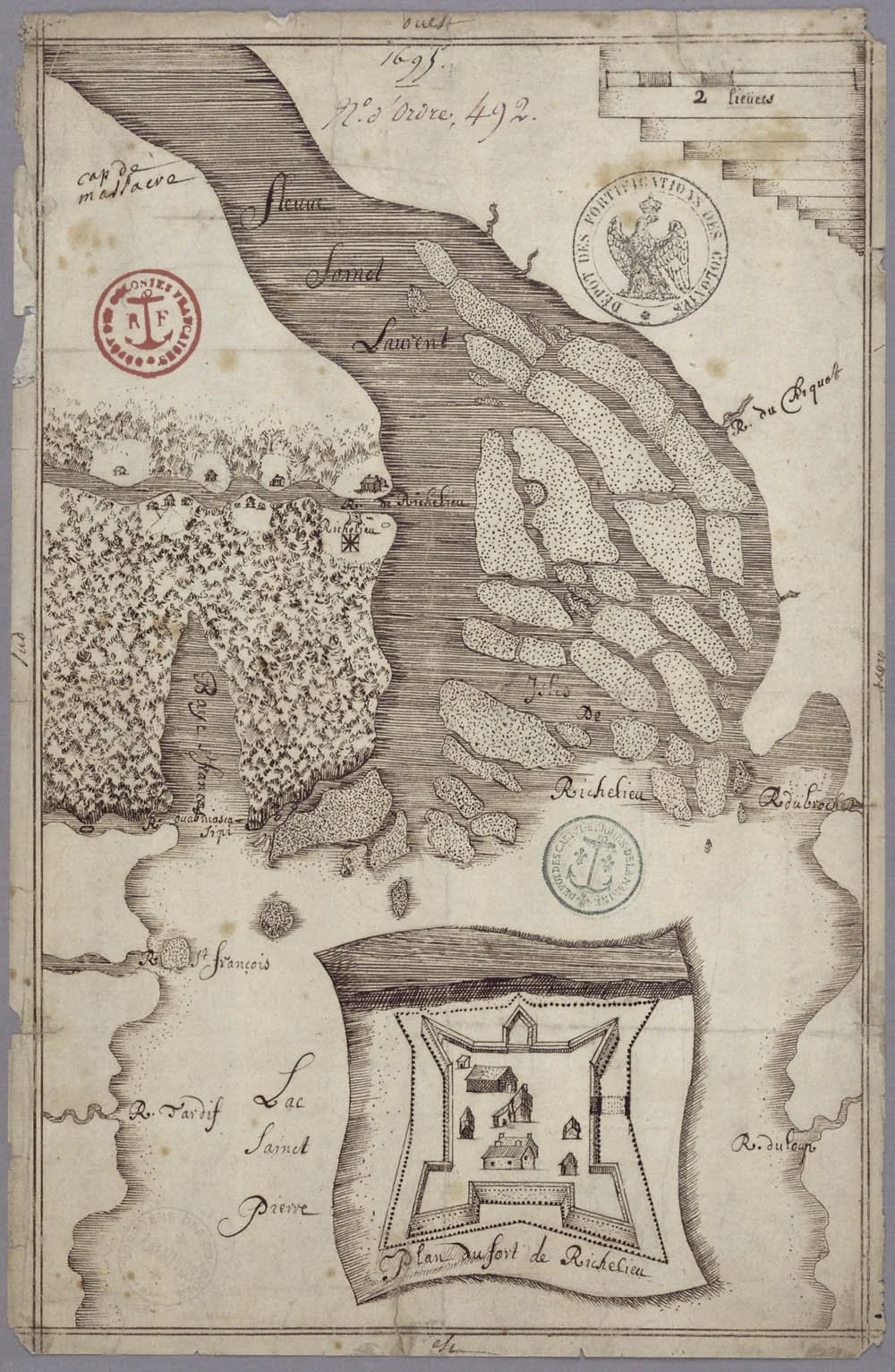

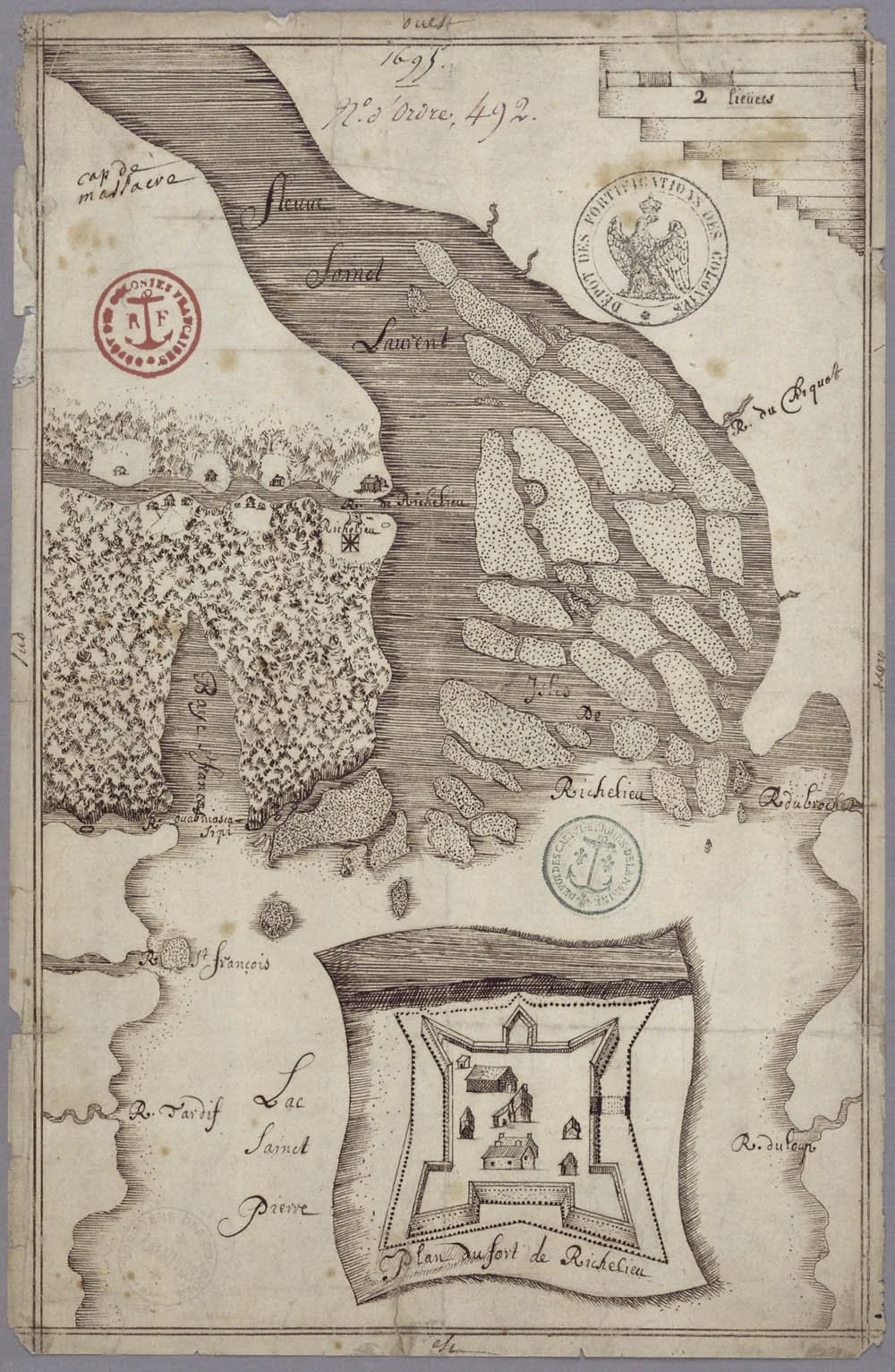

Plan du fort de Richelieu, 1695 — at the confluence of the Richelieu and St. Lawrence rivers at Sorel, showing the Îles de Richelieu. François Séguin wintered here with the St-Ours Company in 1665–1666.

Fort Richelieu stood at the mouth of the Richelieu River where it meets the St. Lawrence — the gateway to the entire defensive corridor. Captain Pierre de Saint-Ours spent the winter of 1665–1666 in the newly built fort at Sorel, and his company, including François Séguin, garrisoned with him.

It was here, in the cramped wooden fort through the long Canadian winter, that soldiers from Picardy and Normandy and Dauphiné first confronted the reality of life in New France. The cold was unlike anything they had experienced in Europe. Supply lines were tenuous. And the enemy — experienced woodland fighters who could appear from the forest without warning — fought nothing like the armies they had trained against.

Yet they endured. And many of them, including François Séguin, began to see in this harsh land not just a military posting, but a future.

Tracy's Campaign Against the Mohawk (1666)

In 1666, Lieutenant General Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy led the regiment in two expeditions south into Mohawk territory. The first, in January under Governor Courcelles, ended badly — the French force became lost in the winter wilderness and suffered from cold and exhaustion. The second, in October under Tracy himself, was decisive.

Some 1,300 men — regulars, militia, and Indigenous allies — marched south along the Richelieu, crossed Lake Champlain, and descended into the Mohawk homeland. Villages were burned. Crops were destroyed. The campaign, though brutal, forced a lasting peace treaty that was signed on 8 July 1667.

This peace is one reason New France survived long enough to grow. For nearly two decades, the Iroquois raids that had terrorized the colony ceased. The countryside became safe for settlement. The Carignan-Salières soldiers — François Séguin among them — had been part of the first successful military defense of the colony, present at one of the most decisive moments in Canadian history.

From Soldier to Settler (1667–1668)

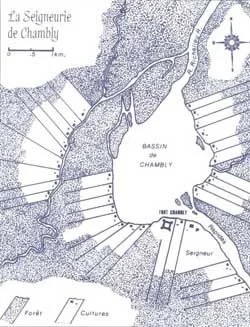

La Seigneurie de Chambly — land concessions based on the seigneurial system. Former soldiers received strips of land along the riverfront. Fort Chambly National Historic Site.

When the Carignan-Salières Regiment was officially disbanded in 1667–1668, about 800 soldiers returned to France. The remaining 400 chose to stay. Officers were encouraged to remain with promises of seigneuries — fiefs containing many square miles. Their troops were promised concessions of land within those same fiefs. They could farm and start a new life in the New World.

The soldiers did not scatter randomly. They clustered near their officers and former forts. Many from the St-Ours Company settled in the Montréal district, along the Richelieu River, or near lands associated with their former captain — who later received the seigneury of Saint-Ours, extending from the St. Lawrence south to the Yamaska River.

Many married the newly arrived Filles du Roi — the King's Daughters sent to populate the colony. This was the moment when men like François Séguin stopped being "troops" and became founders of families. The transition from royal soldier to colonial settler was, in many cases, the most consequential decision these men would ever make.

Commemorative plaque at Boucherville listing the 22 soldiers of the Carignan-Salières Regiment who settled there between 1669 and 1695. François Séguin dit Ladéroute appears in the final line. Société d'histoire des Îles-Percées.

A commemorative plaque erected by the Société d'histoire des Îles-Percées lists the 22 soldiers of the regiment who settled at Boucherville between 1669 and 1695. Among them: Pierre Abirou dit Larose, Julien Allard dit Labarre, François Balan dit Biron, Claude Cognac dit Lajeunesse, François Deguire dit Larose, Gilles Dufault dit Lebreton, Antoine Dupré dit Rochefort, Antoine Émery dit Coderre, Pierre Favreau dit Deslauriers, Christophe Février dit Lacroix, Germain Gauthier dit Saint-Germain, Gilbert Guilleman dit Duvillars, Bernard Joachim dit Laverdure, Jean de Lafond dit Lafontaine, Jean Lamarche, Pierre Lancougnier dit Lacroix, Jean Pagésy dit Saint-Amand, Claude Pastourel dit Lafranchise, Jean-Baptiste Poirier dit Lajeunesse, Louis Robert dit Lafontaine, Pierre Sauchet dit Larigueur — and François Séguin dit Ladéroute.

Related Case Study

The Death That Never Was

Correcting a 320-year-old error in the François Séguin dit Ladéroute death date. For over three centuries, genealogical databases recorded his death as 9 May 1704. But when two daughters' marriage contracts revealed their father was "absent due to illness" in November 1700 and their mother was a "widow" by October 1701, documentary analysis proved the 1704 burial belonged to a different man entirely.

View Case Study →Captain Pierre de Saint-Ours (1640–1724)

The man who commanded François Séguin's company led a remarkable life of his own. Pierre de Saint-Ours was the son of Henri de Saint-Ours and Jeanne de Calignon, a line descending from Pierre de Saint-Ours (Petrus de Sancto Orso), first of the name, who flourished about 1330. He abandoned a military career and hereditary estates in Dauphiné to seek his fortune in the New World.

On 8 January 1668, Saint-Ours married Marie Mullois at Champlain; eleven children were born of this union. About the same time, he was invested with the seigneury of Saint-Ours on the Richelieu River, between the lands of his brother officers Saurel and Contrecoeur. He built a manor-house of timber on the St. Lawrence and some of his soldiers settled around him.

Saint-Ours commanded a detachment in Frontenac's 1673 expedition to Lake Ontario, when Fort Cataracoui was built. He served on advisory committees to the governor and intendant. He commanded at Chambly in 1679, and during Phips' siege of Quebec in 1690, Frontenac entrusted him with command of a battalion. In August 1701, he led the funeral procession of Kondiaronk, the great Huron leader. On 14 June 1704, the King named him knight of the order of Saint-Louis.

His reward for a lifetime of service was meagre. In 1686, Governor Denonville reported that the Saint-Ours family, with ten children, had lacked wheat for eight months of the year. Yet he had established his family name in New France and created one manor in that chain of about a hundred that the Carignan-Salières officers built in the new land. He died in October 1724 on his manor at the age of 84.

When he drew up his will in 1704, Captain Pierre de Saint-Ours bequeathed 400 livres to the soldiers whom he had previously commanded. The name of François Séguin appeared on the list of beneficiaries — proof that the bond between officer and men endured across four decades.

Our Soldier-Ancestors in the Carignan-Salières Regiment

Key Dates: The Carignan-Salières Regiment in New France

Source Documents & Images

The Forts

The Regiment

Boucherville Settlement

Sources & Further Reading

- Séguin-Pharand, Yolande. François Séguin ou L'impossible défi. Association des Séguin d'Amérique, 1992

- Laforest, Thomas J. Our French Canadian Ancestors, Vol. 1. The LISI Press, 1983

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography: Saint-Ours, Pierre de

- Carignan-Salières Regiment — Wikipedia (ship arrival dates and company assignments)

- Société d'histoire des Îles-Percées — Commemorative plaque, Boucherville

- Fort Chambly National Historic Site — Parks Canada

- Kenneth Seguin, Association des Séguin d'Amérique (additional research via Facebook)