Following the Canoe Routes: How the Fur Trade Families Moved Between the Interior and Quebec

Following the Canoe Routes

If your French-Canadian ancestor married an Indigenous woman in the pays d'en haut and their children appear in Quebec parish records, they followed the water. Understanding the canoe routes helps explain why families appear—and disappear—from the records.

Genealogists researching French-Canadian voyageurs often encounter a puzzling pattern: a man appears in Quebec records, disappears for years, then resurfaces—sometimes with a wife and children who seem to have materialized from nowhere. The explanation lies in the geography of the fur trade. These families weren't stationary; they moved along an extensive network of waterways that connected Montreal to the heart of the continent.

Understanding these routes isn't just historical background—it's a practical research tool. When you know how families traveled, you know where to look for records.

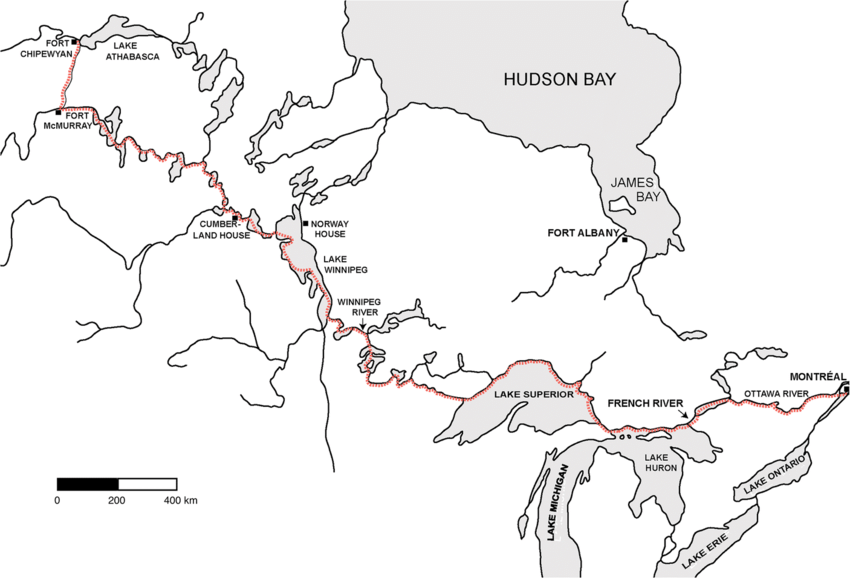

The Voyageurs Highway: the dotted line marks the canoe route from Montreal through the Great Lakes, across Lake Winnipeg, and northwest to Fort Chipewyan in the Athabasca country—a journey of over 3,000 miles that fur trade families traveled regularly.

The Fur Trade Highway

The canoe routes of the fur trade formed an interconnected highway system stretching from Montreal to the Rocky Mountains and beyond. Voyageurs paddled these routes annually, carrying trade goods west in spring and furs east in autumn. Their Indigenous wives and Métis children often traveled with them—or waited at strategic posts along the way.

The main artery connecting the St. Lawrence settlements to the upper Great Lakes. From Lachine (near Montreal), voyageurs paddled up the Ottawa River, across Lake Nipissing, and down the French River to Georgian Bay and Lake Huron.

Key stops: Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Oka, various portages along the Ottawa

From the St. Mary's River rapids (Baawitigong), voyageurs crossed the vast expanse of Lake Superior to the rendezvous point at Fort William (now Thunder Bay). This was the transfer point between the Montreal brigades and the interior canoes.

Key stops: Sault Ste. Marie, Michipicoten, Fort William

From Fort William, smaller canoes carried men and goods into the interior—via Lac La Pluie (Rainy Lake), Lake of the Woods, Lake Winnipeg, and beyond to the Saskatchewan, Athabasca, and Mackenzie river systems.

Key stops: Lac La Pluie, Fort Garry, Cumberland House, Fort Chipewyan

Permanent missions along the routes—like Oka, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, and later Red River—were where Catholic voyageurs could formalize marriages, baptize children, and create the records genealogists rely on today.

Key missions: Oka (Sulpician), Michilimackinac, Prairie du Chien, Red River

Frances Anne Hopkins traveled the canoe routes herself and painted what she saw. This is how fur trade families moved—crowded into birchbark canoes, paddling the same waterways for thousands of miles, season after season.

Why Travel Hundreds of Miles for a Wedding?

Country marriages (à la façon du pays) were recognized and respected within fur trade communities. So why would a voyageur and his Indigenous wife make the arduous journey from the interior to a mission like Oka for a Catholic ceremony?

Most fur trade travel happened in open-water months (May-October). But some ceremonies—like Gabriel Guilbault's January 1801 marriage at Oka—occurred in winter. This suggests the family had traveled east the previous autumn and wintered near Montreal, or that Gabriel had transitioned to working closer to Quebec. Winter dates in parish records can indicate families who were settling permanently in the east, or voyageurs on extended leave between contracts.

The Journey: Baawitigong to Oka

To illustrate what these journeys entailed, consider the route a family like Gabriel Guilbault and Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe would have followed from the St. Mary's Rapids to the Sulpician mission at Oka—a journey of roughly 800 miles.

Following the Water: St. Mary's Rapids to Oka

Sault Ste. Marie → Lake Huron

Departing from Baawitigong, the family would paddle or portage around the rapids, then enter Lake Huron. Following the North Channel along the Manitoulin Island shore, they'd reach the mouth of the French River.

French River → Lake Nipissing

Up the French River—a challenging stretch with numerous portages—to Lake Nipissing. This was the height of land between the Great Lakes and Ottawa River watersheds.

Lake Nipissing → Mattawa River

Across Lake Nipissing to the Mattawa River, then a portage to the Ottawa River. This was the traditional route used by Indigenous peoples for millennia before European arrival.

Ottawa River → Montreal Region

Down the Ottawa River toward the St. Lawrence—passing numerous rapids requiring portages. The final stretch brought travelers to the Lake of Two Mountains region, where Oka's Sulpician mission awaited.

Arrival at Oka

The mission of L'Annonciation at Oka—established by the Sulpicians in the early 18th century—served both the local Mohawk and Algonquin communities and the fur trade families who passed through. Here, a priest could perform baptisms, marriages, and record the families for posterity.

Anna Jameson's 1837 sketch of the St. Mary's Rapids—Baawitigong—where Gabriel and Marie Josephte likely met. This was the first major waypoint on the journey from the interior to Montreal.

This journey—covering roughly 800 miles—would take several weeks by canoe under good conditions. With a family including young children, the pace would be slower. The voyageurs knew every portage, every campsite, every rapid along the way. For Marie Josephte, an Ojibwe woman of the Saulteaux nation, traveling these waterways would have drawn on generations of Indigenous geographic knowledge.

The Records Follow the Routes

When you understand how fur trade families traveled, you understand where to look for records. A voyageur who worked in the Lake Superior region might have children baptized at Michilimackinac, married at Oka, and buried at Red River. Following the canoe routes means following the paper trail across multiple archives and jurisdictions.

What This Means for Your Research

Practical Applications

Search Multiple Parishes

Don't limit your search to one location. A family might appear in Montreal-area parishes (Oka, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Lachine), Great Lakes missions (Michilimackinac, Sault Ste. Marie), and western posts (Red River, Prairie du Chien). Cast a wide geographic net.

Mind the Gaps

Years-long gaps in Quebec records don't mean your ancestor died or disappeared. He was likely working in the interior, where records were sparse or nonexistent. Check fur trade company records (NWC, HBC) to fill these gaps.

Look for Legitimization Records

When a voyageur married formally, children born "à la façon du pays" were often legitimized in the same ceremony. These records can list multiple children at once, with ages that help reconstruct the family's timeline in the interior.

Map the Journey

Plot your ancestor's known locations on a map. Do they follow the canoe routes? If he appears at Sault Ste. Marie and later at Oka, the connection makes geographic sense. If the locations seem random, you may be conflating two different individuals.

Case Study: The Guilbault Family

Gabriel Guilbault met Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe at Baawitigong (Sault Ste. Marie) in the early 1790s. They lived together "à la façon du pays" for over a decade, raising four children in the fur trade world. In January 1801, they traveled to Oka, where Father Leclerc baptized Marie Josephte, married them formally, and legitimized their children—all in two days of ceremonies.

Later NWC records (1816, 1820, 1821) place Gabriel at Lac La Pluie and in the Athabasca country—showing he continued working the interior routes into his late 50s. His life followed the water, and so does the paper trail.

The 1801 register at Oka where Father Leclerc recorded Marie Josephte's full Ojibwe name, married her to Gabriel, and legitimized their four children—the documentary evidence of a family that had traveled hundreds of miles from the pays d'en haut.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY