Baawitigong: The Place of the Rapids

Baawitigong

At the St. Mary's River, where Lake Superior tumbles twenty-one feet into the lower Great Lakes, two worlds met. For the Ojibwe, it was Baawitigong—the gathering place. For the voyageurs, it was the strategic gateway to the fur trade interior. Somewhere at this crossroads, Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe and Gabriel Guilbault's lives first intersected.

One Place, Many Names

The name isn't really about the town. It's about the water.

Sault is an old French word meaning a leap, a jump, or rapids. So "Sault Ste. Marie" essentially means the rapids of Saint Mary. Long before Europeans arrived, the Anishinaabe people called this place Baawitigong—"the place of the rapids." The water has always been the identity.

When Father Leclerc recorded Marie Josephte's identity in 1801, he wrote that she was "de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur"—of the Saulteaux Nation on Lake Superior. The Saulteaux. The Saulteurs. The "Leapers" or "Jumpers." French explorers called these Ojibwe people by this name because they lived at the sault—the rapids—and because of their remarkable ability to navigate those dangerous waters.

This was Marie Josephte's homeland. The place where her people had gathered for over two thousand years.

Ojibwe fishermen in the St. Mary's Rapids, 1901. Standing in birchbark canoes, using long poles and dip nets, they practiced the same techniques their ancestors had used for millennia—including during Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe's lifetime.

Why the Rapids Mattered

The St. Mary's River rapids consist of a series of fast-flowing cascades with a total drop of approximately twenty-one feet—the point where Lake Superior releases its waters toward the lower Great Lakes. This wasn't a vertical waterfall but a churning, turbulent three-quarters of a mile of whitewater that made the location both treacherous and extraordinarily valuable.

The rushing water created one of nature's most abundant fisheries. As Lake Superior's waters tumbled through the rapids, they became highly oxygenated, flowing over clean cobble and gravel riverbeds that provided ideal spawning habitat. The turbulent, shallow environment supported a rich ecosystem that fed countless fish—most importantly, adikameg, the lake whitefish.

"I was watching with a mixture of admiration and terror several little canoes which were fishing in the midst of the boiling surge, dancing popping about like corks. The manner in which they keep their position upon a footing of a few inches, is to me as incomprehensible as the beauty of their forms and attitudes, swayed by every movement and turn of their dancing barks is admirable."

Early European observers recorded with amazement that skilled Ojibwe fishermen could catch several hundred large whitefish in a single hour using traditional dip nets. The rapids acted as a natural funnel, concentrating the fish in predictable locations where they could be efficiently harvested year-round. This constant, reliable food source sustained the large seasonal encampments that made Baawitigong the great gathering place of the Anishinaabe world.

Anishinaabe fishermen at the St. Mary's River. The birchbark canoes and dip net fishing methods depicted here had remained essentially unchanged for centuries.

Baawitigong was known as "The Gathering Place of the Three Fires Confederacy" because diverse tribes would meet here—not only to harvest the abundant whitefish but to engage in politics, religious rituals, trade, and the strengthening of alliances. The Ojibwe (Keepers of the Faith), the Potawatomi (Keepers of the Fire), and the Odawa (the Traders) all gathered here, along with the Cree from the north, the Menominee from the west, and visitors from throughout the Great Lakes region.

When the Voyageurs Came

In 1668, Jesuit missionary Father Jacques Marquette established a mission at this existing Indigenous settlement and applied the name Sault Ste. Marie to the entire area around the rapids. For more than a century afterward, it remained a single community shaped by Indigenous life, the fur trade, and French (later British) rule.

By the 1790s—the decade when Gabriel Guilbault likely arrived in the region—the North West Company had established a trading post at the base of the rapids. A quick glance at any map revealed why this location mattered: whoever held Baawitigong held the key to the entire upper Great Lakes fur trade.

The North West Company established its depot at the St. Mary's River in the 1790s—the very years when Gabriel Guilbault and Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe's lives first intersected.

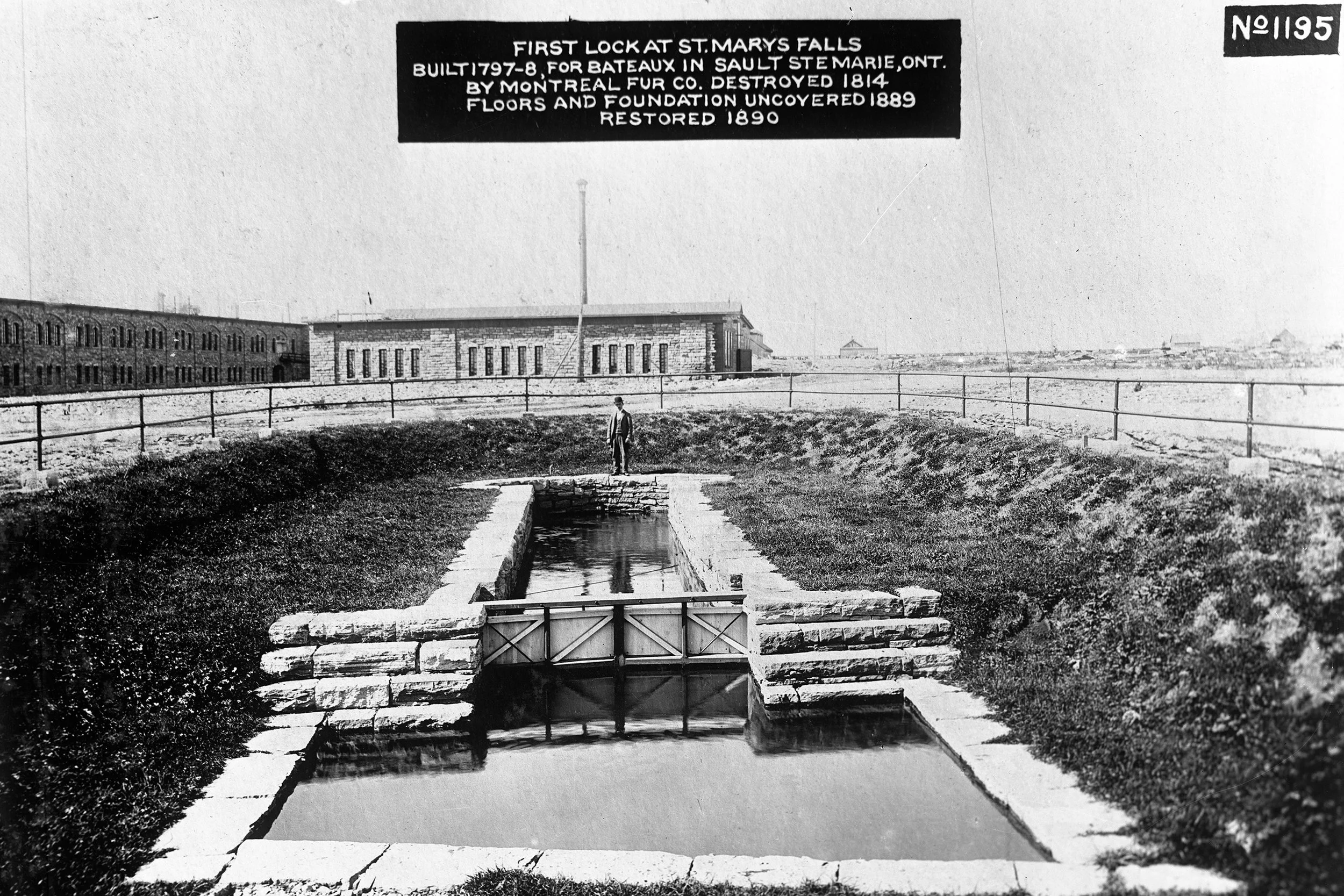

The rapids that had nourished the Ojibwe now presented a challenge to European commerce. Because the cascades were unnavigable, every piece of cargo moving between the Great Lakes had to be unloaded and carried overland—a portage that gave the area's main street, Portage Avenue, its name. In 1797, the North West Company built an 800-meter canal to bypass the rapids, complete with the first lock in the Great Lakes system.

It was the same year that saw Marie Josephte give birth to her son Joseph Claude Guilbault—one of the four children who would later be legitimized at their parents' church wedding in Oka.

Born around 1760 to the Baawitigowininiwag—the "People of the Rapids." Her spirit name, meaning "Half-Sky Woman" or "Half-Day Woman," was given according to Ojibwe tradition. She grew up in a world where the rhythms of life followed the seasons: maple sugaring in spring, fishing and gathering in summer, wild rice harvesting in fall, hunting in winter.

Her people controlled the strategic waterways and served as expert navigators, traders, and "Rapids Pilots" who guided travelers safely through the turbulent waters.

A French-Canadian man who traveled to the pays d'en haut—the Upper Country—likely as a voyageur or independent trader. The fur trade depended not just on economic exchange but on social bonds. Marriages between French traders and Indigenous women created kinship networks that facilitated trade, provided translators and cultural intermediaries, and produced the Métis communities that would become a distinct people.

Gabriel entered Marie Josephte's world, and their union—à la façon du pays—would last over a decade.

Where Two Lives Crossed

We cannot know exactly how Gabriel and Marie Josephte met. Perhaps it was during one of the great gatherings at Baawitigong, when the banks of the river filled with canoes from across the region. Perhaps it was at one of the smaller trading posts along the Lake Superior shore. What we do know is that their relationship produced at least six children over more than a decade—a union lived "à la façon du pays," according to the custom of the country.

Anna Jameson's 1837 sketch of Wayishky's lodge at Sault Ste. Marie. Traditional Ojibwe dwellings like this would have been familiar to Marie Josephte's generation.

Imagine the scene at Baawitigong in the 1790s: along the riverbanks, traditional Ojibwe lodges stood near the warehouses of the fur traders. The sound of Anishinaabemowin mingled with French and later English as voyageurs, traders, and Indigenous families negotiated the complex relationships that defined the fur trade era. The rushing waters provided a constant backdrop—the same waters that had drawn Marie Josephte's ancestors here for millennia.

For Marie Josephte, her relationship with Gabriel likely did not represent a simple transition from one world to another. Ojibwe women of her generation often maintained their traditional knowledge and practices even as they adapted to the changing circumstances brought by the fur trade. They continued to harvest wild rice (manoomin), process fish and furs, create birchbark containers and beadwork, and pass their languages and stories to their children.

Gabriel and Marie Josephte likely met here at Baawitigong in the early 1790s. They lived "à la façon du pays" for over a decade, raising four children in the fur trade world. But in January 1801, they made the long journey east to Oka—a trip of several hundred miles by canoe and portage along the established trade routes connecting Lake Superior to Montreal via the Ottawa River.

Why travel so far? While country marriages were recognized within fur trade communities, Catholic traders often sought formal church ceremonies when a priest was available. The Sulpician mission at Oka offered permanent religious infrastructure, and formalizing the marriage legitimized their children in colonial records—providing them legal standing, inheritance rights, and access to opportunities in French-Canadian society. The journey from Baawitigong to Oka wasn't unusual; it was part of the rhythm of fur trade life, where families moved between the interior and the settlements along routes the voyageurs knew by heart.

William Armstrong captured this peaceful moment along the St. Mary's River, showing the tranquil landscape that belied centuries of cultural exchange.

The Geography of Connection

The St. Mary's River wasn't just a location—it was a crossroads where Indigenous expertise met European commerce, where personal relationships formed that would create entire family lines, and where a woman named Abitakijikokwe met a man named Gabriel Guilbault. Understanding this place helps us understand how their lives came together, and why their descendants carry both heritages.

The Rapids: Then & Now

When we trace ancestors in the fur trade era, understanding the geography is essential. Marie Josephte's identification as being "de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur" tells us not just her tribal affiliation but her likely geographic origin—the St. Mary's River region, Baawitigong, where her people had gathered for centuries. This knowledge shapes where we might look for additional records, what other families she might have been connected to, and how her descendants dispersed across the continent.

The Guilbault Line Series

The Guilbault Line: A Documentary Biography Series →

The complete case study tracing the voyageur family from Quebec to the present.

Abitakijikokwe: The Woman Behind the Name →

The full story of what Father Leclerc's 1801 record preserved about Marie Josephte's identity.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY