When One Ancestor Appears Twice: Catherine Lemesle

When One Ancestor Appears Twice

If you've done any deep genealogical research, you've probably encountered a phenomenon that seems mathematically impossible: the same ancestor appearing in multiple places on your family tree. It's called pedigree collapse, and once you understand it, you'll realize it's not just possible—it's inevitable.

In my own research, I discovered that Catherine Lemesle—a Fille du Roi who arrived in Quebec in 1671—is my 8th great-grandmother twice. Not two different women with the same name. The exact same person, appearing in two separate branches of my family tree that eventually converged when her great-great-grandchildren married each other 85 years after her death.

This is her story, and the story of how two family lines that began with her eventually became one.

The Mathematics of Ancestry

Before we dive into Catherine's story, let's talk numbers. If you go back 10 generations—roughly to the late 1600s—you theoretically have 1,024 8th great-grandparents. Go back another generation, and that number doubles to 2,048. Continue the pattern, and by 20 generations ago, you'd have over a million ancestors in that single generation alone.

But here's the problem: there weren't a million people living in any single region 500 years ago. The math doesn't work unless some of those "ancestor slots" are filled by the same people appearing multiple times.

This is pedigree collapse. It's not a bug in your family tree—it's a feature of human history.

In colonial Quebec, where communities were small and options for marriage partners were limited, pedigree collapse happened frequently. Studies suggest that French Canadians today have, on average, about half as many unique ancestors as the theoretical maximum would suggest. The same families intermarried generation after generation.

In my case, the collapse happens through Catherine Lemesle, who had two children whose descendants would eventually marry each other—reuniting the family lines she had started.

Who Was Catherine Lemesle?

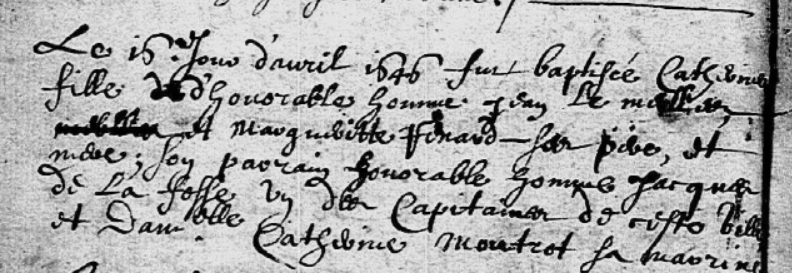

Catherine Lemesle was baptized on April 16, 1646, in the parish of Saint-Pierre-du-Châtel in Rouen, one of France's largest cities. Her father, Jean Lemesle, was a marchand bourgeois—a merchant of comfortable means. Her mother was Marguerite Renard.

By 1671, both of Catherine's parents had died. As a single woman with some inheritance but no family protection, her options in France were limited. But across the Atlantic, King Louis XIV was offering something remarkable: free passage to New France, a royal dowry supplement, and the prospect of marriage to one of the many single men desperate for wives in the struggling colony.

These women became known as the Filles du Roi—the King's Daughters.

The Voyage

In the summer of 1671, Catherine boarded Le Prince Maurice at Dieppe. The ship carried 86 Filles du Roi that year, chaperoned by Madame Anne Gasnier Bourdon, the widow appointed by Intendant Jean Talon to oversee the King's Daughters program.

The voyage across the Atlantic took six to eight weeks. Catherine was approximately 25 years old—older than many of her fellow passengers, most of whom were between 16 and 25. She arrived in Quebec on July 30, 1671, carrying a dowry of 200 livres, fifty of which came directly from the King.

Within eleven months, she was married.

Marriage to Pierre Morin

Pierre Morin was a former soldier in the Carignan-Salières Regiment, the famous military force sent to New France in 1665 to fight the Iroquois. By 1671, the campaign was over, and soldiers who stayed in the colony were promised land grants and wives from France.

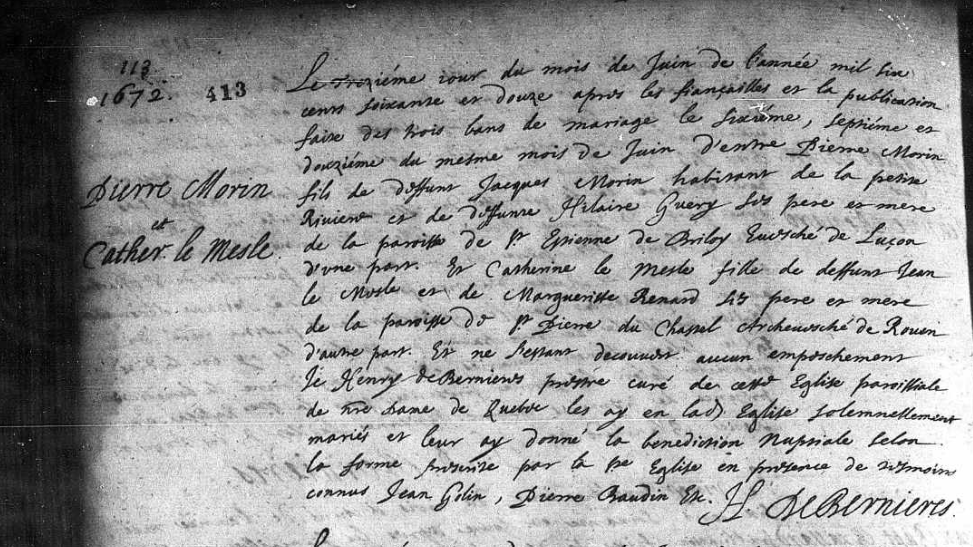

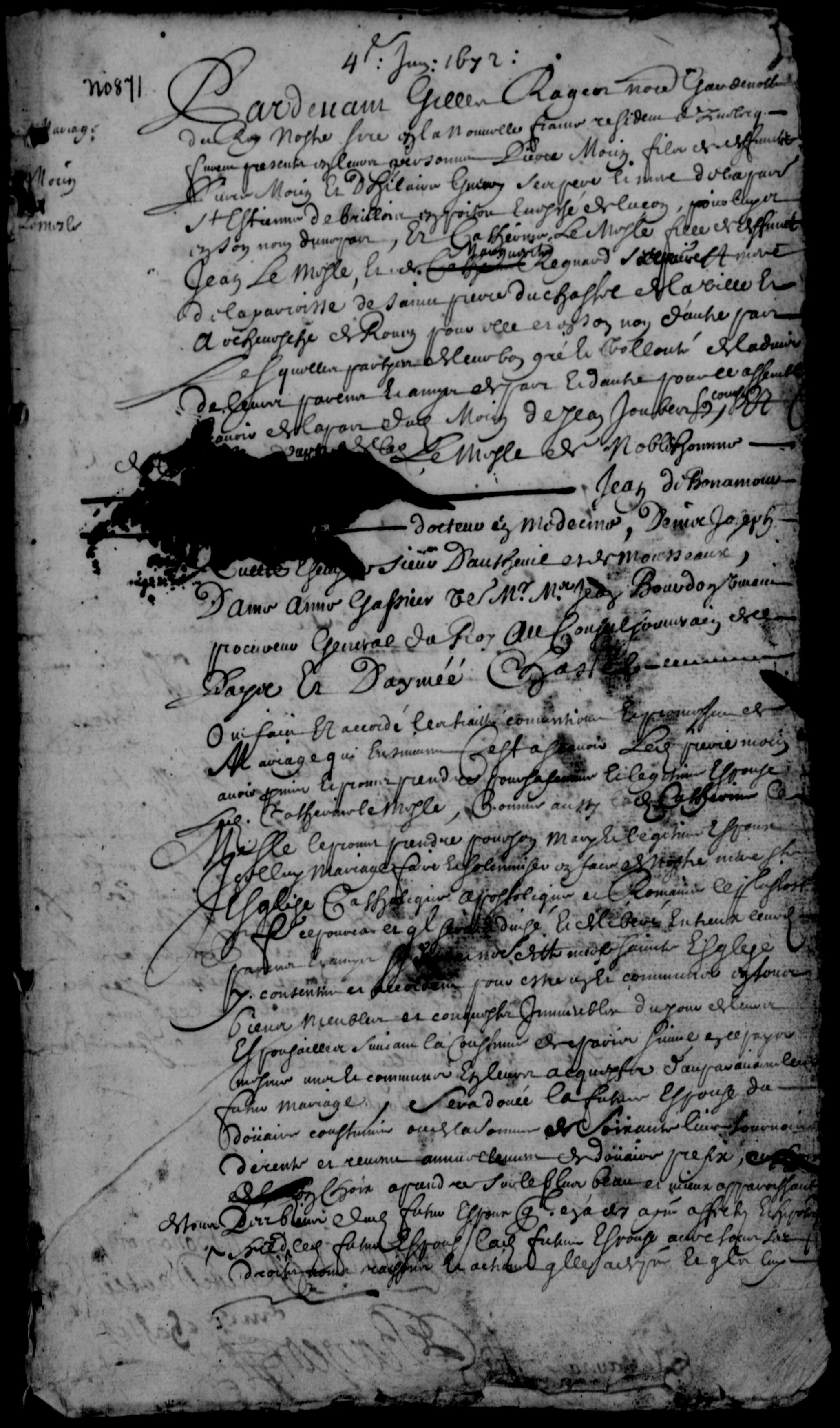

Pierre was from Saint-Étienne-de-Brillouet in western France. On June 4, 1672, he and Catherine signed a marriage contract before notary Gilles Rageot. Nine days later, they were married at Notre-Dame-de-Québec.

Over the next eighteen years, they would have eight children. Five survived to adulthood. And two of those five would become the starting points of the two family lines that would eventually reunite in my ancestry.

The Two Paths

Catherine's firstborn was Marie Anne Morin, baptized July 22, 1673. Her fifth child was Joseph Morin, baptized January 6, 1682. These two siblings—nine years apart in age—would each start family lines that would grow separately for 85 years before converging again.

Catherine Lemesle & Pierre Morin

Married 1672, Quebec CityPath 1: Through Marie Anne (1673)

- Marie Anne Morin (1673-1743)

married Guillaume Deguise, 1691 - Marie Catherine Deguise (1704-1731)

married Charles Guilbault - Charles Gabriel Guilbault (1731-1784)

married Marie Charlotte Morin, 1757

Path 2: Through Joseph (1682)

- Joseph Morin (1682-1735)

married Marie-Anne Brideau, 1704 - Joseph Morin II (1709-1781)

married M.C. Charles Croquelois - Marie Charlotte Morin (1738-1767)

married Charles Gabriel Guilbault, 1757

Do you see what happened? In 1757, Charles Gabriel Guilbault married Marie Charlotte Morin. He was the great-great-grandson of Catherine Lemesle through her daughter Marie Anne. She was the great-great-granddaughter of Catherine Lemesle through her son Joseph. Neither may have known they shared a common ancestor. But when they married, they reunited family lines that had been separate for 85 years.

Their son—Gabriel Guilbault, the voyageur who would marry an Ojibwe woman named Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe—carried Catherine Lemesle's genetic legacy through both his parents. And so do I.

What This Means for DNA

Pedigree collapse has practical implications for genetic genealogy. When you descend from the same ancestor through two different lines, you potentially inherit DNA from that ancestor twice—through two separate paths of transmission.

A Note on DNA Inheritance

By the 8th great-grandparent level (10 generations back), you theoretically inherit about 0.1% of your DNA from each ancestor. But DNA inheritance is random—you might inherit slightly more or slightly less, and there's even a chance you inherited zero DNA from a specific distant ancestor. When you descend from the same person twice, your expected inheritance roughly doubles, but the randomness still applies. The practical effect is that DNA matches who also descend from Catherine Lemesle might share more DNA with me than expected for our relationship level.

Why This Matters for Your Research

If you're researching French-Canadian ancestry, expect to find pedigree collapse. The small colonial population, the limited marriage pools, and the tendency for families to intermarry within geographic regions all contributed to a highly interconnected population.

Here's what to watch for:

Research Tip: When you encounter pedigree collapse, document it clearly. I use separate "path" designations (Path 1, Path 2) to track each line of descent from the doubled ancestor. This makes it easier to explain to relatives and to keep the relationships straight in your own mind.

The Broader Significance

Catherine Lemesle was one of approximately 800 Filles du Roi who came to New France between 1663 and 1673. Together, these women became the maternal ancestors of millions of French Canadians and their descendants across North America. Studies suggest about two-thirds of French Canadians can trace at least one line to a Fille du Roi.

But to descend from the same Fille du Roi through two different children—to have that ancestor's legacy doubled in your heritage—illustrates something profound about the interconnectedness of colonial Quebec society. These weren't isolated families; they were a web of relationships, constantly crossing and recrossing through marriages, godparent relationships, and shared community life.

Catherine couldn't have known, when she stepped off Le Prince Maurice in 1671, that her descendants would eventually marry each other. She couldn't have imagined that 350 years later, someone would piece together the documentary trail of her life—her baptism in Rouen, her marriage contract in Quebec, the baptisms of her children—and discover that she appears twice in a single family tree.

But here we are. And now you know her story.

Want to Explore Your French-Canadian Ancestry?

Storyline Genealogy specializes in French-Canadian research, including Filles du Roi connections, voyageur families, and complex multi-generational analysis.

Learn About Our ServicesWant to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY