Marriage à la façon du pays: The Unions That Built a Nation

Marriage à la façon du pays

During the 1700s and 1800s, marriages between French fur traders and Indigenous women were fundamental social and economic institutions in North America. These unions created strategic alliances that facilitated the fur trade and led to the emergence of the distinct Métis culture—and they left a paper trail that genealogists can follow today.

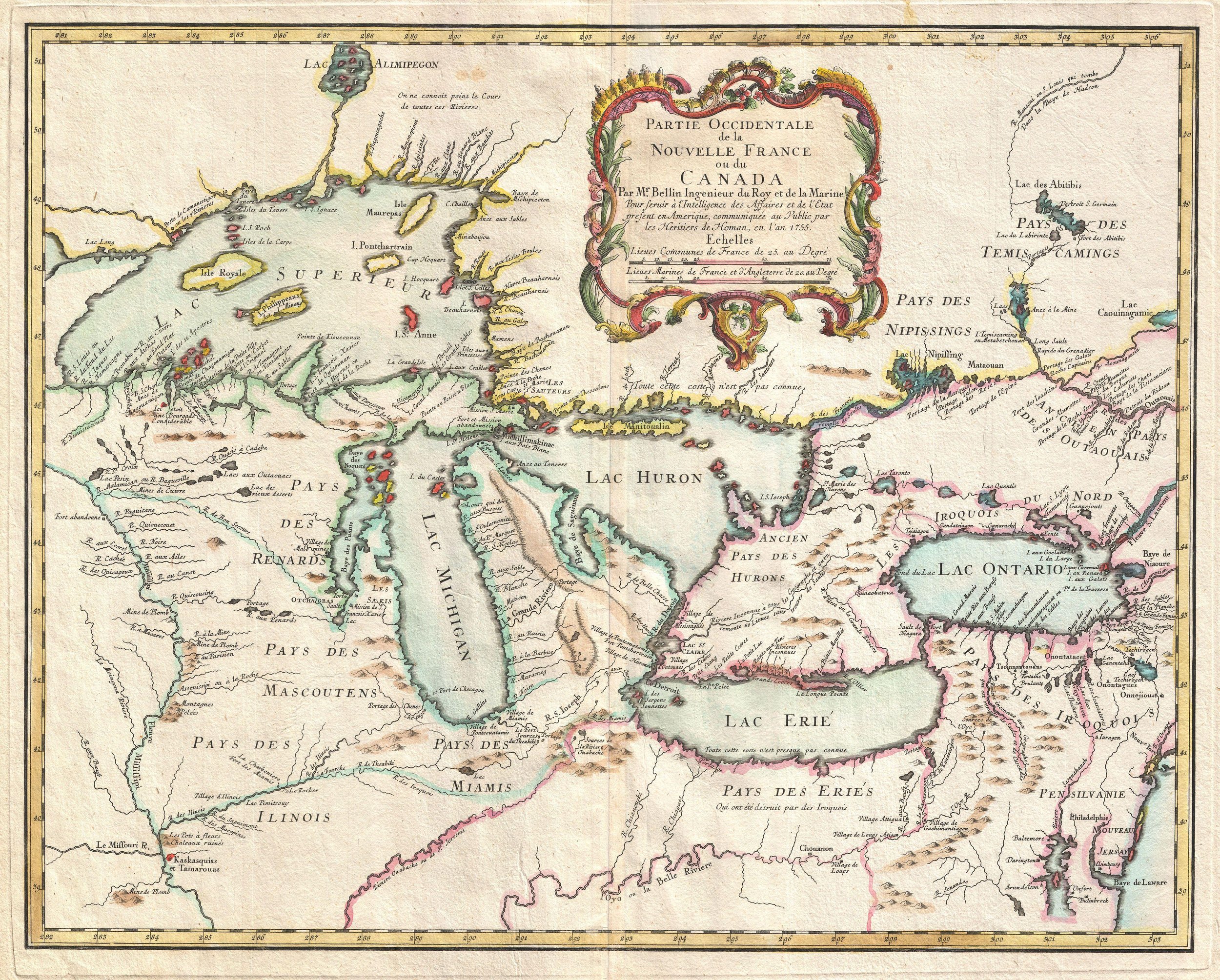

A 1755 map by Jacques Nicolas Bellin showing the Great Lakes region—the Pays d'en Haut (Upper Country). This territory was dominated by various Indigenous nations, with the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi among the most important trading partners of French voyageurs.

In the parish registers of Oka Mission, I found her name: Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur. For over two centuries, she had remained largely invisible in historical narratives—until genealogical research unearthed her identity in an 1801 marriage record. Her story opens a window into one of the most significant yet underexplored chapters of North American history.

The French phrase mariage à la façon du pays ("marriage according to the custom of the country") describes unions that blended Indigenous and European customs to create something entirely new. Canadian historian Sylvia Van Kirk called these marriages "the basis for a fur trade society." Because few French women immigrated to the interior wilderness, traders formed these relationships to integrate into Native kinship networks—relationships that were far more than casual arrangements.

How These Unions Worked

While the Catholic Church often refused to recognize these unions as legal agreements because they lacked Church rituals, they were considered legitimate by Native tribes and fur trade companies. The marriages typically involved a "bride price" paid to the woman's family—horses, guns, blankets, or other European goods.

The benefits flowed both ways. Fur traders gained access to tribal hunting grounds, protection, and crucial survival knowledge. Native families secured a reliable supply of European goods—metal tools, textiles, and firearms that transformed their daily lives. A Native woman who married a high-ranking trader often gained elevated social standing and first access to new technologies, which altered traditional workloads (using copper pots instead of clay, for example).

What the historical records often miss is just how essential Indigenous women were to the traders' survival. They weren't passive partners—they were indispensable.

"These marriages came with the expectation that trade between the woman's relations and the trader would be secured, and that aid would be mutually provided in times of need."

Where to Find These Families in the Records

For genealogists researching French-Canadian or Métis ancestry, understanding where these unions were documented is crucial. Because mariage à la façon du pays unions were often not recognized by the Catholic or Anglican churches, they rarely appeared in standard parish registers. Instead, evidence surfaces in unexpected places.

Key Record Sources

A Special Resource: Tanguay's Dictionary

Cyprien Tanguay's Dictionnaire Généalogique des Familles Canadiennes (1887, 7 volumes) includes a list of men who married Indigenous women in New France at the very end of the last volume. While summary in form, these entries can be expanded with further research into individual names. The complete dictionary is available for free download from BAnQ (Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec).

The Métis Legacy

The children of these unions developed a unique identity, often speaking both French and Indigenous languages such as Cree or Ojibwe. They served as crucial intermediaries and employees within the fur trade hierarchy—bridging two worlds. Over time, they formed the distinct Métis people, now recognized as one of Canada's three Aboriginal groups alongside First Nations and Inuit.

For French-Canadian genealogists, understanding these unions explains why so many family trees lead back to Indigenous ancestors—and why those connections were often obscured in the historical record. The women who made these alliances possible deserve to be remembered not as footnotes, but as founders.

Floral designs created by Ojibwe artists represent the flowers and plants found close to their woodland homes. This artistic tradition—passed down through generations of Indigenous women—continues today as a living connection to the culture of the Pays d'en Haut.

Continue the Series

In Part 2: Abitakijikokwe—The Woman Behind the Name, we explore one of these women in depth: Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe, whose Ojibwe spirit name and Saulteaux tribal identity were both preserved by an extraordinary priest at Oka in 1801.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY