Abitakijikokwe: The Woman Behind the Name

Abitakijikokwe

On January 26, 1801, Father Leclerc at L'Annonciation in Oka did something extraordinary: he recorded the full Ojibwe identity of an Indigenous bride—her personal spirit name and her tribal affiliation—preserving both for posterity when most priests simply wrote "Sauvagesse."

What Father Leclerc Preserved

de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur

For most Indigenous women who married French-Canadian voyageurs, history recorded only a single word: Sauvagesse. No name. No nation. No origin. Just a generic French term meaning "Indigenous woman." But in January 1801, at the Sulpician mission of L'Annonciation at Oka, a priest named Leclerc took the time to ask—and to listen—and to write down the full identity of the woman standing before him.

That act of attention preserved something genealogically priceless: both Marie Josephte's personal Ojibwe spirit name and her tribal affiliation. Fewer than 0.1% of Indigenous ancestors have such thorough documentation. For her descendants—including me—this record opens a door to understanding who she was and where she came from.

Two Identities, One Woman

Father Leclerc's record gives us two distinct pieces of information about Marie Josephte's Indigenous identity—each carrying its own meaning and significance.

This name appears rooted in Anishinaabemowin (the Ojibwe language) with three components:

Abit- (Abitawaa) meaning "half," "middle," or "halfway"

-gijig- (Giizhig) meaning "sky," "day," or "heaven"

-kwe (Ikwe) meaning "woman"

In Anishinaabe tradition, such names were often "vision names" received through ceremony, symbolizing a spiritual connection to the celestial realm. The translation "Half-Sky Woman" suggests someone positioned between earth and sky—a spiritually significant identity.

The Saulteaux (also called Saulteurs) were Ojibwe people associated with Sault Ste. Marie—Baawitigowininiwag in Ojibwe, meaning "People of the Rapids."

French explorers called them Saulteurs (from saut, meaning "leap" or "waterfall") because they lived at the 21-foot drop where Lake Superior flows into the St. Marys River.

This tribal designation tells us she came from the Lake Superior Ojibwe—expert navigators, traders, and the people who controlled the strategic Straits of Mackinac.

The translation of "Abitakijikokwe" as "Half-Sky Woman" represents a linguistic interpretation based on Anishinaabemowin roots. Spirit names carried deep personal and ceremonial significance that cannot be fully captured in translation. What we can say with confidence is that this appears to be a vision name connecting her to the celestial realm—a name likely given through ceremony and carried throughout her life. Historical French records sometimes rendered this name as "Abitakijikok8e," with the "8" being Jesuit shorthand for the soft "ou" or "w" sound common in Algonquian languages.

Colonial priests typically had no interest in Indigenous names or tribal affiliations. A woman like Marie Josephte would usually appear in records only as "Sauvagesse" or "une femme sauvage." Father Leclerc's careful documentation—her personal name, her nation, her approximate age, her geographic origin—represents an exceptional act of record-keeping that preserved her identity when so many others were erased.

The 1801 Record at L'Annonciation

L'Annonciation d'Oka: Then & Now

The Saulteaux: People of the Rapids

Marie Josephte's tribal designation—de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur—connects her to one of the most strategically important Indigenous nations in the fur trade. The Saulteaux controlled the crucial waterways around Sault Ste. Marie, where Lake Superior's waters drop into the St. Marys River through turbulent rapids.

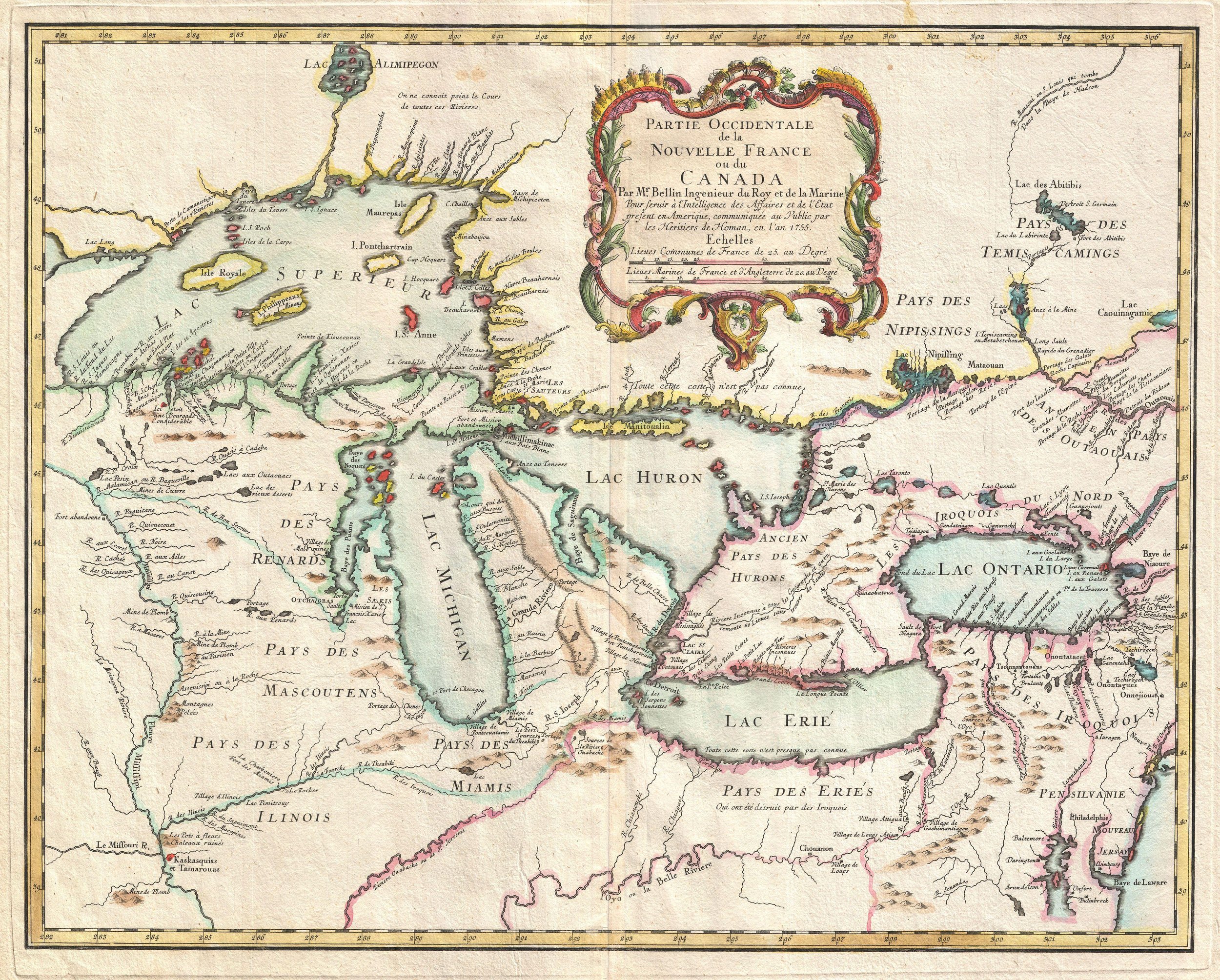

A 1755 map by Jacques Nicolas Bellin showing the Great Lakes region. Lake Superior (upper left) was the homeland of Marie Josephte's people, the Saulteaux—the "People of the Rapids" who controlled the strategic waterways of the fur trade.

The French called these Ojibwe people Saulteurs ("Leapers" or "Jumpers") because of their remarkable ability to navigate the dangerous rapids at Sault Ste. Marie. Standing in birchbark canoes, they would "jump" through the boiling water using long poles and dip nets to catch massive amounts of whitefish. They also served as "Rapids Pilots," guiding fur traders safely through the fast-moving water. This geographic and navigational expertise made them invaluable partners—and formidable negotiators—in the fur trade.

Why Her Name Matters

For descendants searching for Métis heritage or First Nations ancestry in the Pays d'en Haut (the Upper Country), Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe represents something profound: a named ancestor. In an era when Indigenous women were routinely erased from the historical record, her full Anishinaabe spirit name was preserved—a testament to her significance and to Father Leclerc's unusual attention to detail.

Floral designs created by Ojibwe artists represent the flowers and plants found close to their woodland homes. This artistic tradition—carried through generations of Indigenous women like Marie Josephte—continues today as a living connection to Ojibwe culture.

Her name connects thousands of modern descendants to their Indigenous heritage. It provides a direct linguistic link to Ojibwe culture and language. And it reminds us that behind every genealogical record is a real woman with a real name—one that carried meaning for her people long before colonial scribes tried to transcribe it.

A Tangible Connection

As part of my research into Marie Josephte, I searched for tangible connections to Ojibwe material culture. On eBay, I found two treasures: an antique Chippewa Ojibwe beaded velvet purse and a petite birch bark basket—objects created using techniques her ancestors perfected over generations. When I hold them, I'm connecting to the same artistic traditions she would have known.

My antique Chippewa Ojibwe beaded velvet purse and birch bark basket—tangible connections to my Ojibwe heritage through Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe.

For Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe

(c. 1760–1813)

Ojibwe woman of the Saulteaux Nation • Wife of Gabriel Guilbault • Mother of six children • My 4th great-grandmother

Half-Sky Woman. That's who she was. And now, after two centuries, her story is finally being told.

This Series

Part 1: Marriage à la façon du pays—The Unions That Built a Nation

Understanding the marriages between French fur traders and Indigenous women that created the Métis people—and where to find these families in the records.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY