Marie Gaillard: Fille du Roi, Matriarch of Two Lines

Marie Gaillard

A Woman Who Shaped a Lineage

Marie Gaillard, Fille du roi, widow twice over, and matriarch of two converging family lines, stands among the most consequential women of early New France. She crossed the Atlantic at 22, buried her first husband before she was 35, merged two families into a household of eleven children, watched her daughter marry her stepson, relocated westward to build a new life, and died at 89—having outlived nearly everyone she had ever known.

Her descendants now number over a million Quebecers. Yet Marie Gaillard left no letters, signed no documents (she could not write), and held no official position. Her power was the power of survival, adaptation, and deliberate family-building in a world where women's choices were constrained but never irrelevant. Through her decisions—whom to marry, how to merge households, which unions to permit—she shaped a lineage that endures to this day.

Marie's Legacy: Two Lines Converge

Through her daughter Madeleine:

Through her second husband's son Pierre:

Marie's household produced the union that permanently bound these two families.

The Decision to Leave: Normandy, 1669

Marie Gaillard was born around 1647 in Ernemont-sur-Buchy, a rural commune in the Seine-Maritime department of Normandy, about 17 kilometres northeast of Rouen. Her parents were Pierre Gaillard (or Daire) and Marie Martin (or Gaillard). Life in Ernemont was agrarian—farming, animal husbandry, local crafts—and shaped by proximity to Rouen's markets and the rhythms of the religious calendar.

When her father died, Marie faced the constrained options available to unmarried women without means. She could remain in Normandy, dependent on relatives or charitable institutions. Or she could take a calculated risk: accept the King's offer of passage to New France, where the desperate shortage of marriageable women meant opportunity.

Marie chose the ocean.

She arrived in Quebec around June 30, 1669, likely aboard the Saint-Jean-Baptiste, carrying goods valued at approximately 200 livres—her dowry and her stake in whatever future she could build. At about 22 years old, she was older than many Filles du roi, perhaps more deliberate in her choice, certainly aware that she was trading the known hardships of Normandy for the unknown dangers of a colonial frontier.

The Surname Confusion: Marie's surname appears inconsistently across records. At her 1669 marriage, she is identified as Marie Daire, daughter of Pierre Daire and Marie Gaillard. In her 1684 marriage contract, her parents appear as Pierre Gaillard and Marie Martin. Her French baptism record has not been located. Her descendants adopted Gaillard.

The First Marriage: A Soldier from Béarn

The man Marie chose—or accepted—as her husband had already survived more than most colonists would experience in a lifetime. Jean Perrier dit Lafleur was born around 1646 in Pau, in southwestern France near the Spanish border. He had enlisted in the La Brisardière Company, sailed to the Caribbean in 1664 to help expel the Dutch from Cayenne, overwintered in Guadeloupe, and then traveled north to New France with the Carignan-Salières Regiment in 1665. He had helped build forts along the Richelieu River and likely marched into Mohawk territory in 1666.

By 1668, when peace was declared with the Iroquois, Jean was one of only three men from his company who chose to remain in New France rather than return to France. He received a land concession in Beauport and transformed himself from soldier to settler. This was the man who appeared in Marie's life in the autumn of 1669—a veteran of imperial warfare, a man who could neither read nor write, but who owned land and needed a wife to help him work it.

Jean's military experience shaped the precarious household Marie would later be forced to hold together alone. A man accustomed to danger may have been less careful with his own life. Whatever the cause, he would be dead within thirteen years of their wedding day, leaving Marie a widow with six children.

Building a Household: Beauport, 1669–1682

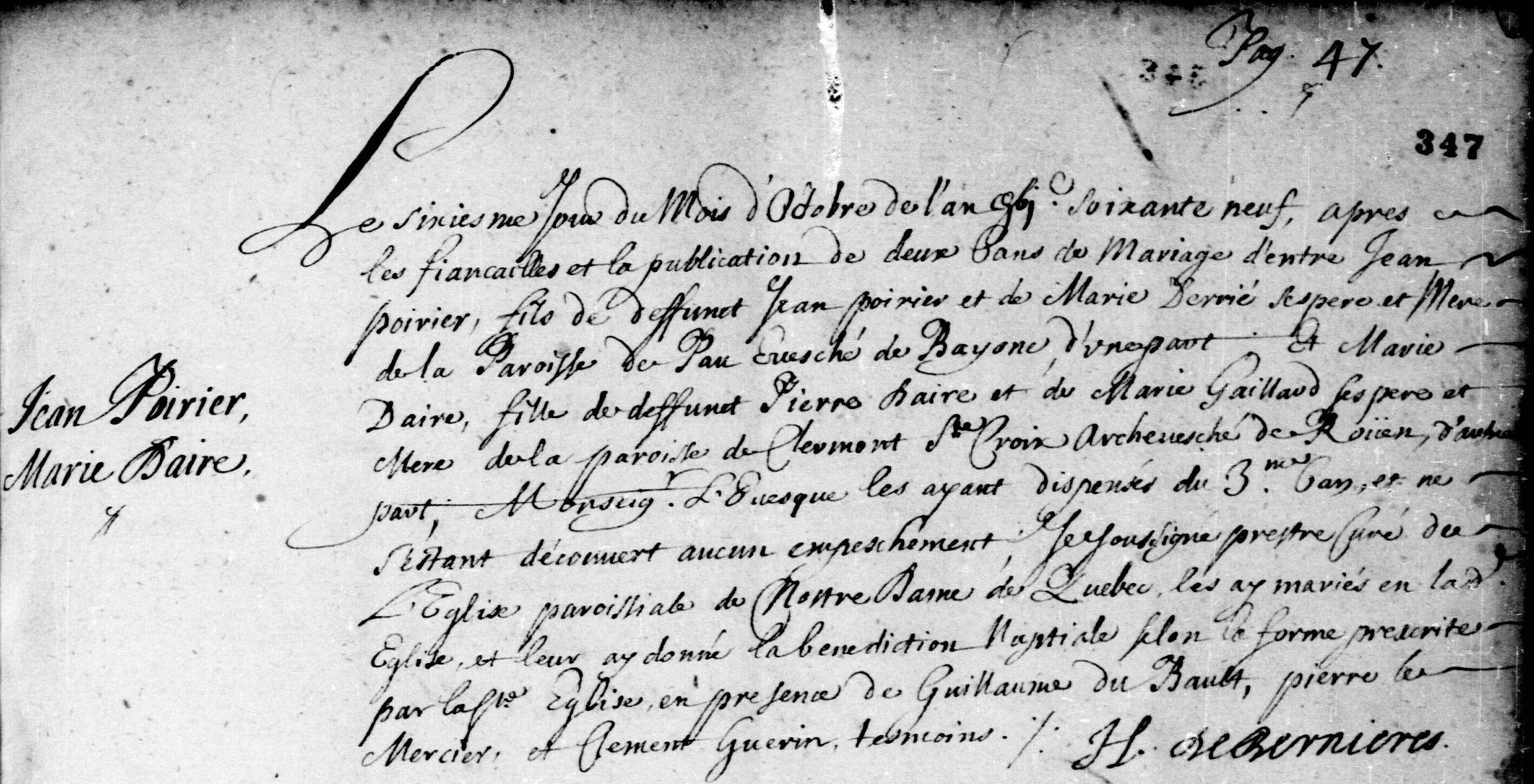

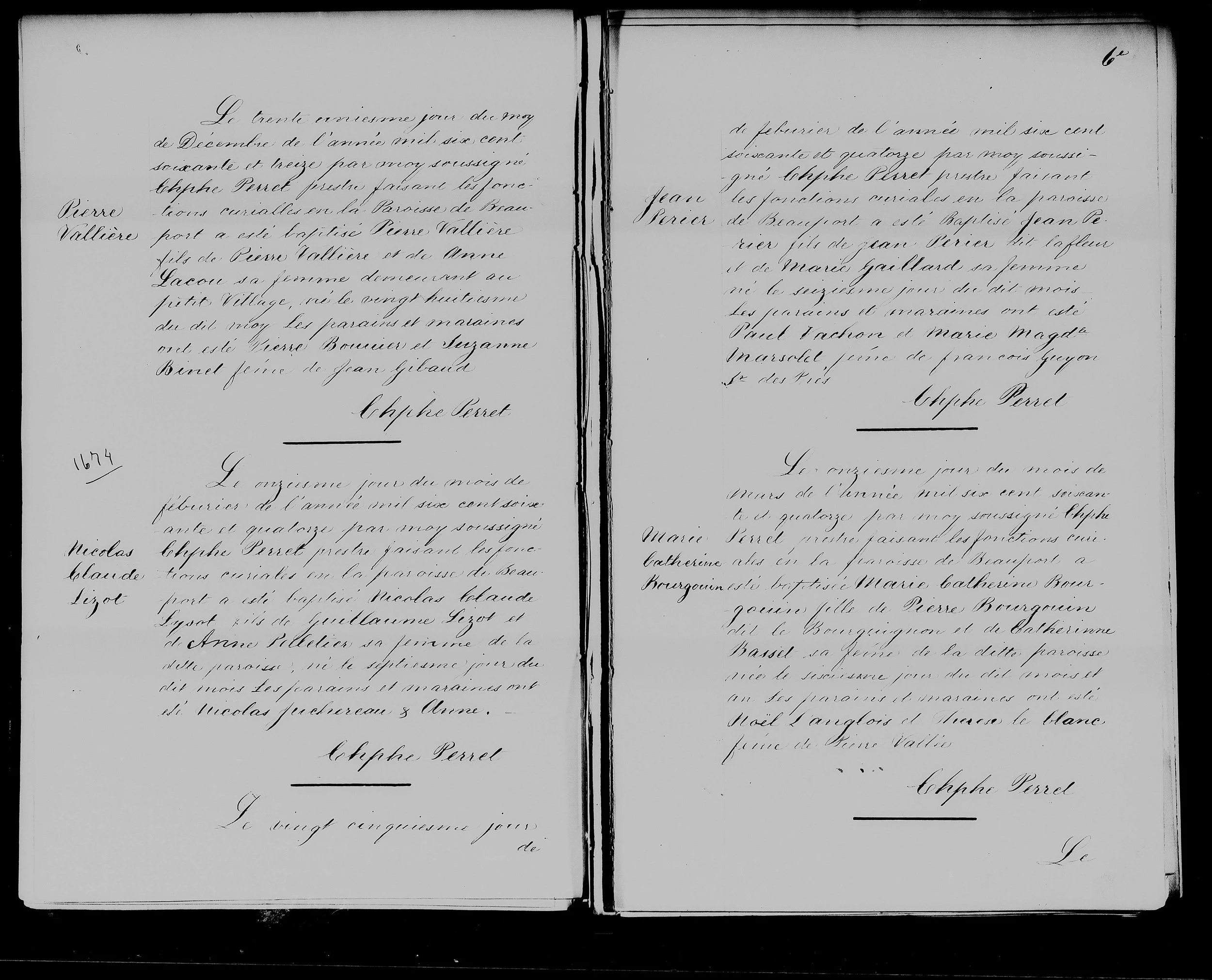

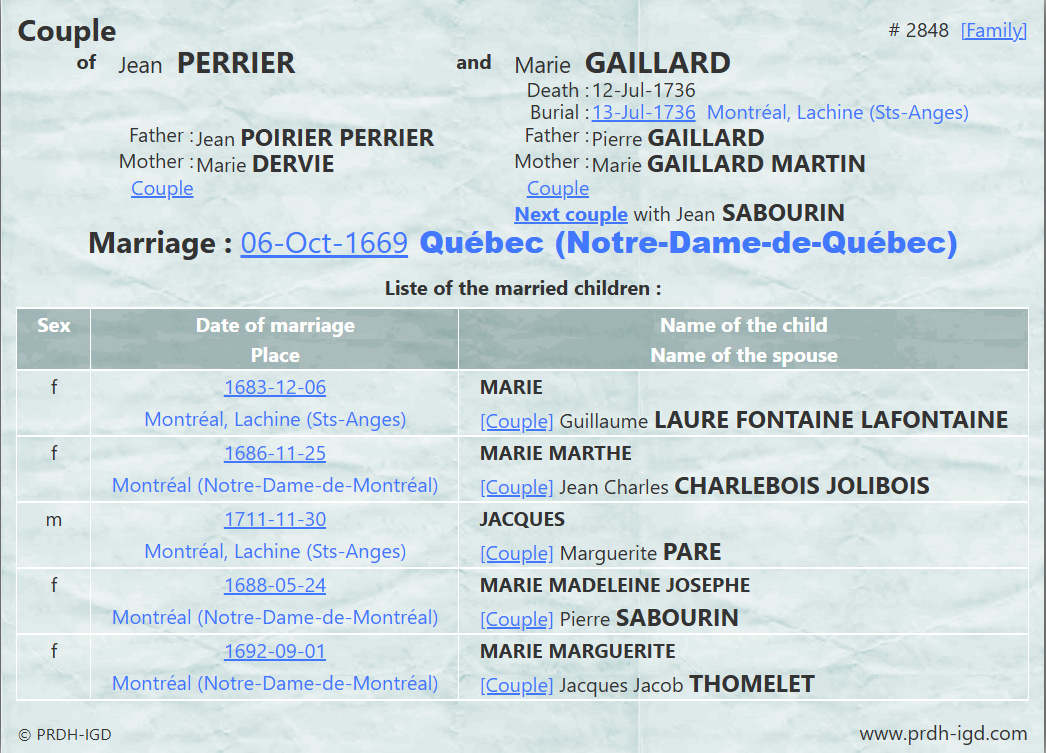

On September 22, 1669, notary Romain Becquet drafted the marriage contract. Marie brought goods valued at 200 livres; Jean promised a douaire prefix of 300 livres. Neither could sign their names. Two weeks later, on October 6, they were married at Notre-Dame de Québec.

Marie was now mistress of a two-arpent concession in Beauport, responsible for transforming raw land into a working farm while bearing and raising children. Over the next twelve years, she would give birth at least seven times:

The 1681 census captured Marie's household in November: Jean Perrier (35), Marie Gaillard (34), and six children ranging from 11 years to 9 months. They owned one gun. No cultivated land. No animals. After thirteen years of marriage, they were still struggling—likely sharecroppers or tenants rather than independent farmers.

Within months of that census, Jean was dead. His burial record has never been found. Marie, at 35, was alone with six children.

Widowhood and the Strategic Remarriage

In the harsh calculus of colonial New France, a widow with six children had few options and little time. Before 1680, about half of all widows remarried within a year of their spouse's death. The reasons were practical: farms required two adults to function, children needed feeding, and the social structure assumed a male head of household for legal and economic transactions.

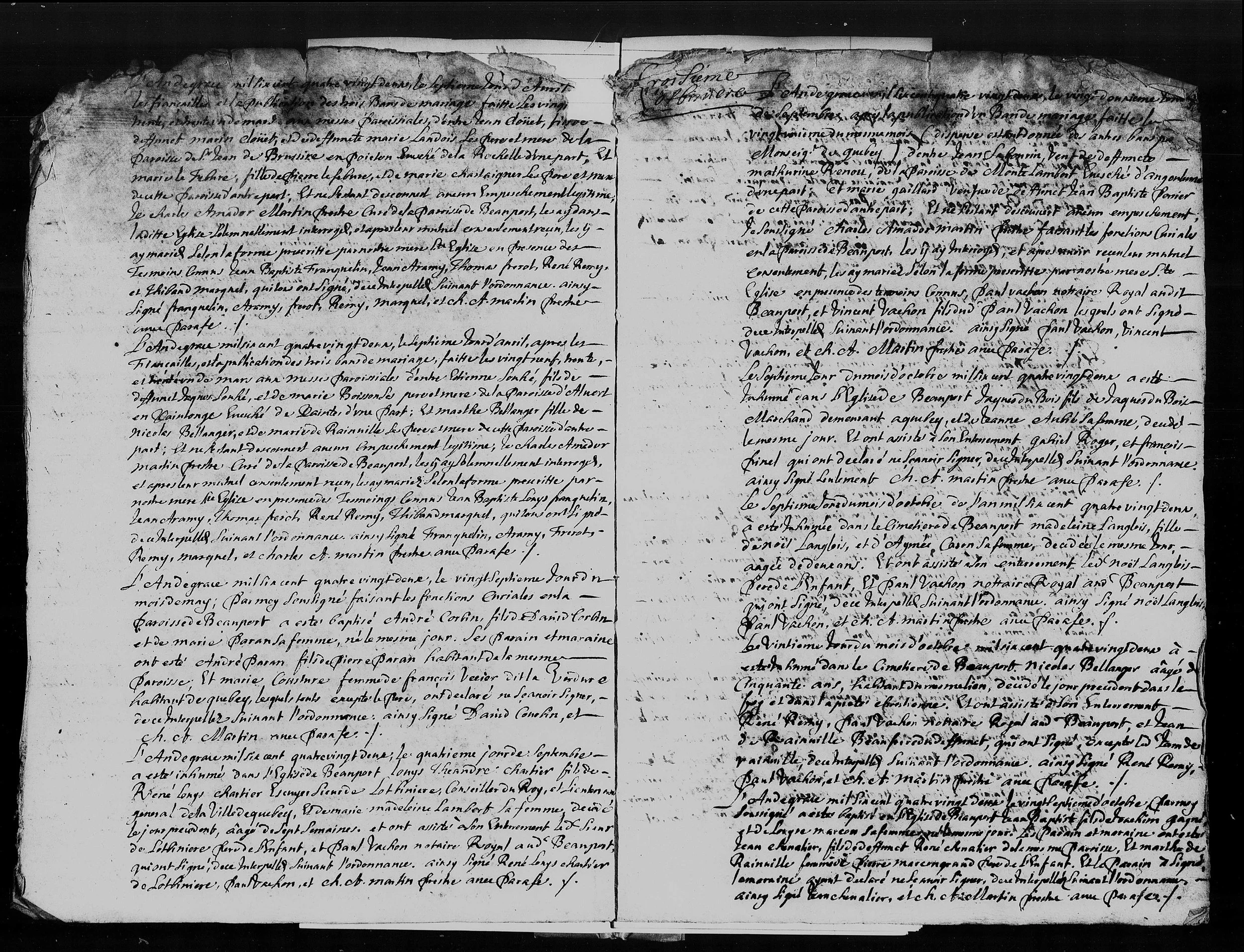

Marie secured her family's survival through marriage to Jean Sabourin, a ploughman from Poitou who was himself a widower with five surviving children. On September 22, 1682—less than a year after Jean Perrier's death—they married in Beauport. Marie was about 35; Jean Sabourin about 41.

This was not romance—it was merger. Marie brought six children; Jean Sabourin brought five. Overnight, she became responsible for a household of eleven children plus two adults. The logistics alone were staggering: feeding, clothing, housing, and managing the labor of what amounted to a small village.

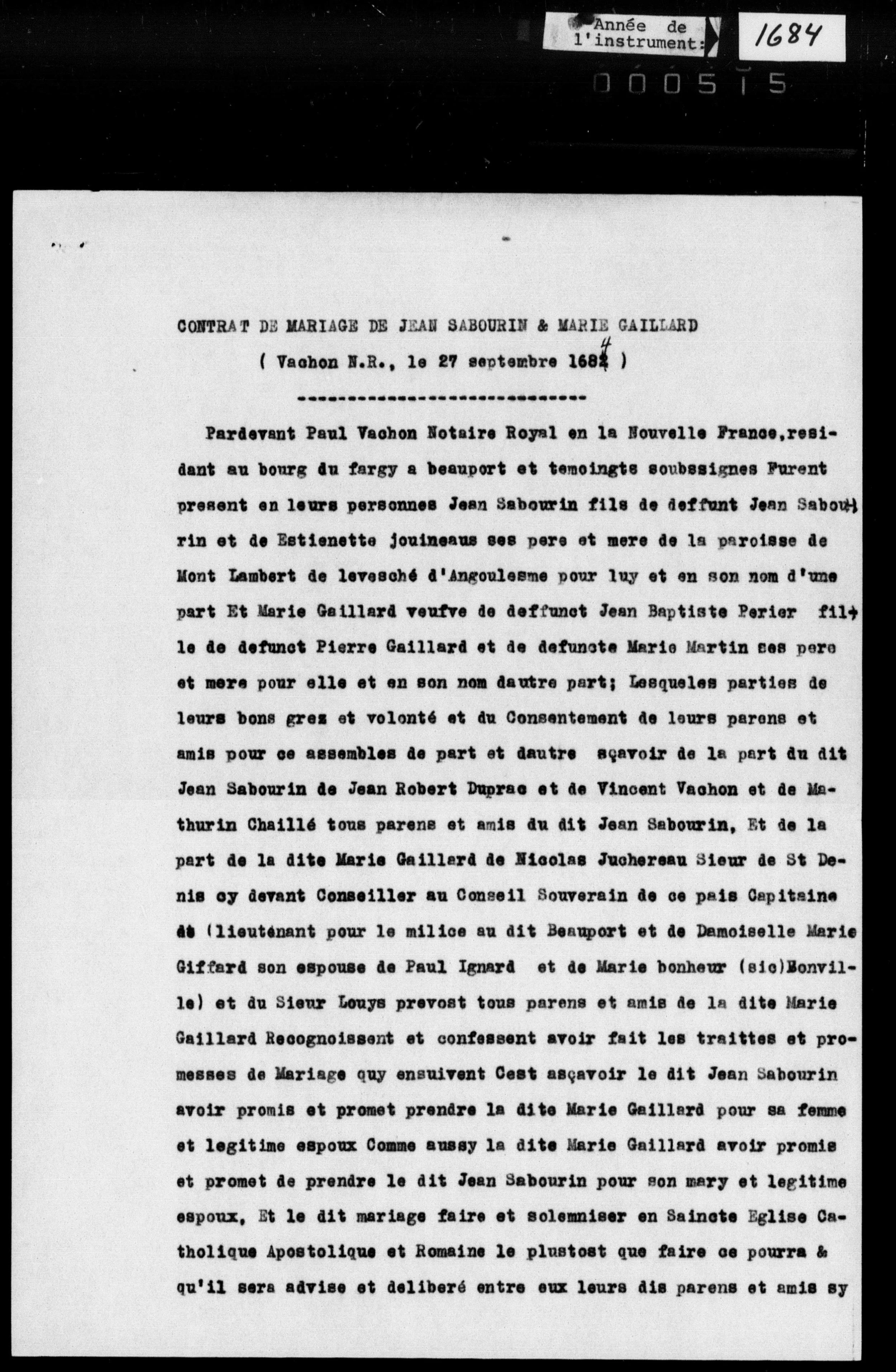

Two years later, on September 27, 1684, Marie and Jean formalized their arrangement with a marriage contract drawn by notary Paul Vachon. Jean endowed Marie with a dower of 500 livres and a préciput of 200 livres—legal protections that would matter if she were widowed again. Neither could sign their names.

Managing the Blended Household

Marie merged two families into a single working unit. The children ranged from toddlers to teenagers, each with their own memories of a dead parent, their own claims on resources and attention:

Marie's Children (Perrier)

- Marie, age 12

- Marie Marthe, age 12

- Jacques, age 10

- Madeleine, age 8

- Marguerite, age ~5

- François, age 2

Jean Sabourin's Children

- Pierre, age ~16

- Jean, age ~14

- François, age ~12

- Marie, age ~10

- Marguerite, age ~8

There were now two Maries, two Marguerites, and two François under one roof. The eldest, Pierre Sabourin, was nearly a man at 16; the youngest, François Perrier, was barely walking. Marie had to integrate these children into a functioning household while managing the farm labor, food production, and domestic work that colonial survival demanded.

Around 1683, Marie and Jean relocated the entire operation westward to the Montréal area. Whether this move was driven by opportunity, necessity, or the need for a fresh start with a merged family, the records do not say. What they do show is that Marie continued to manage property transactions and family decisions for decades to come.

The Union That Bound Two Families

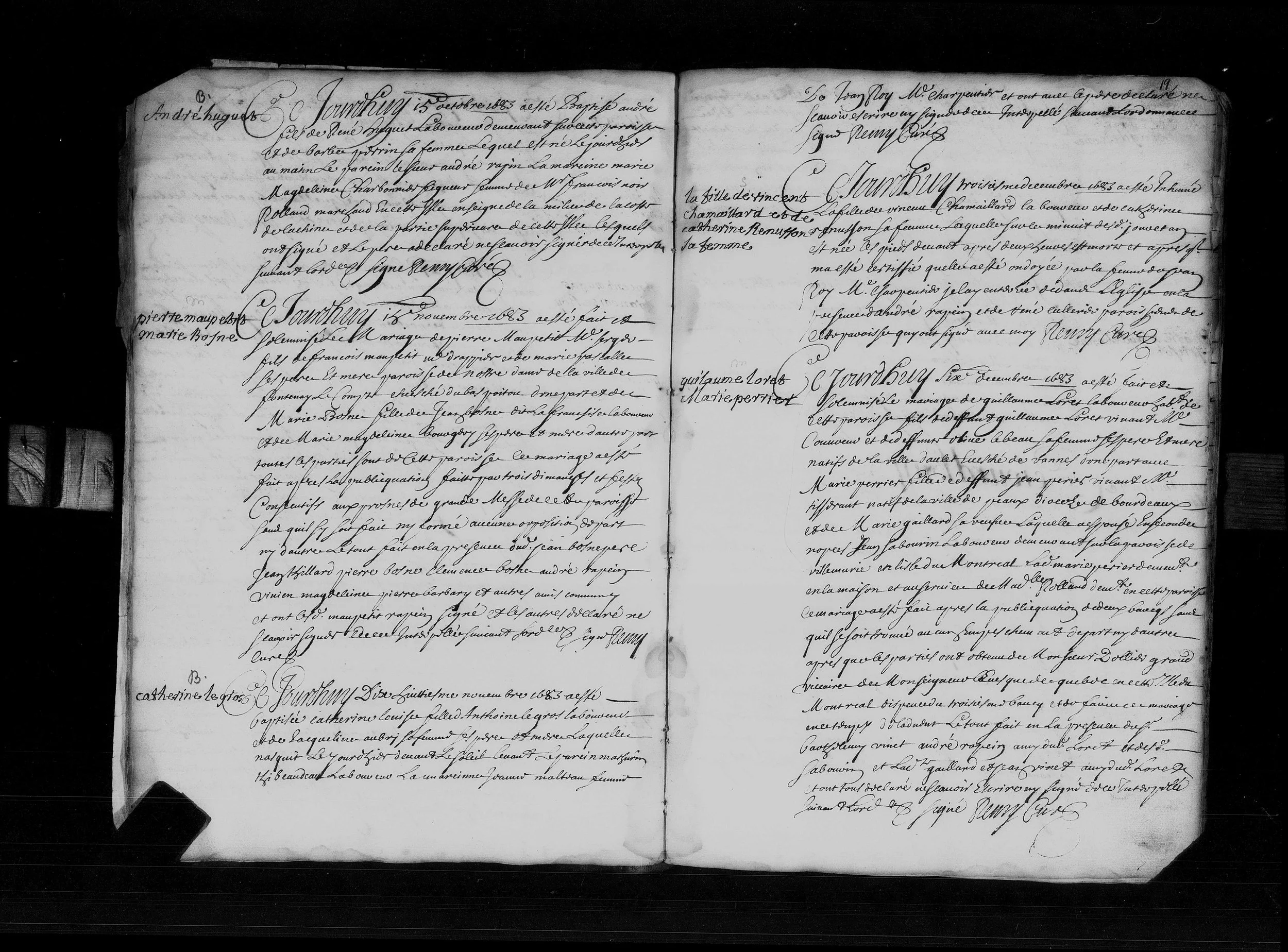

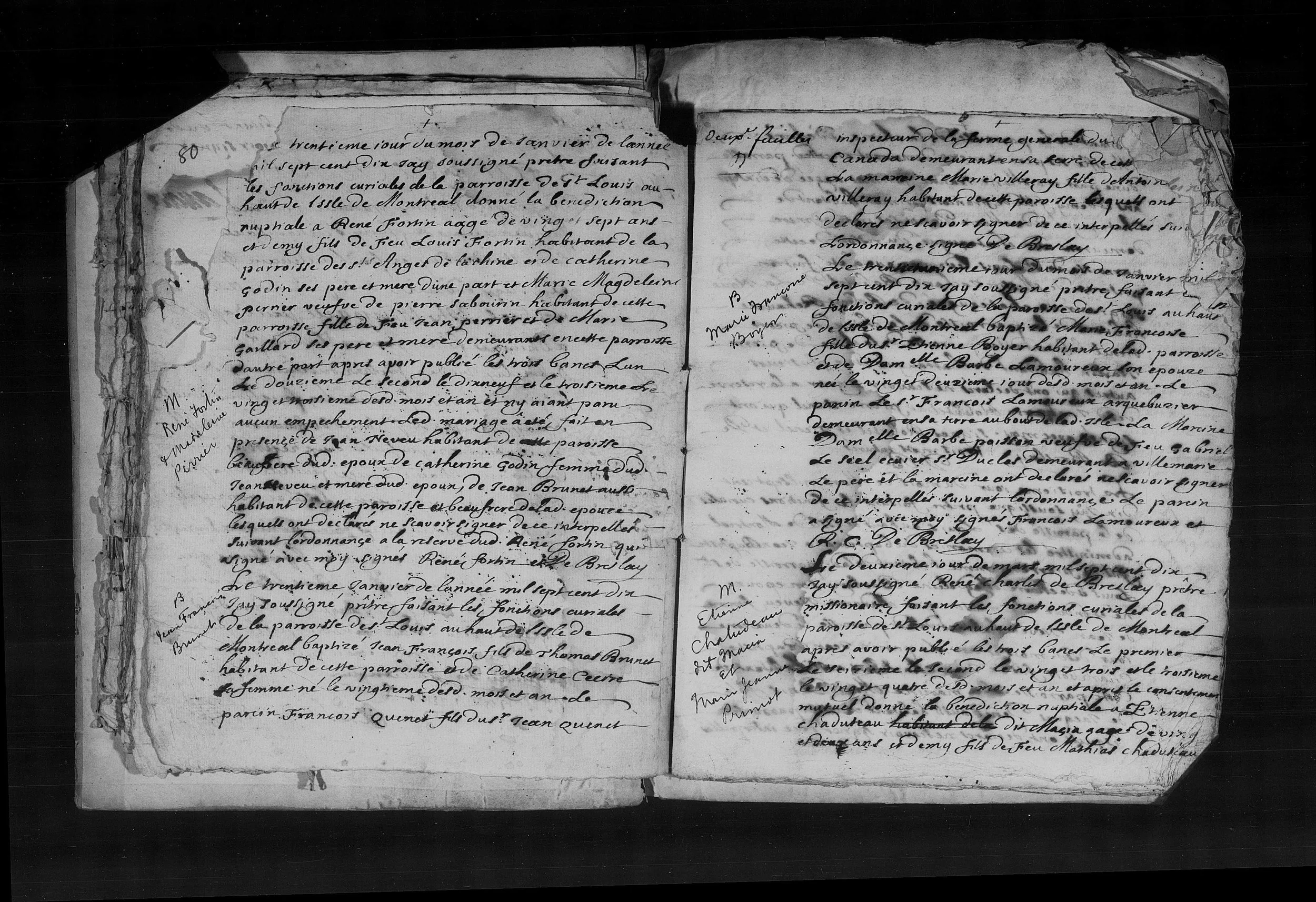

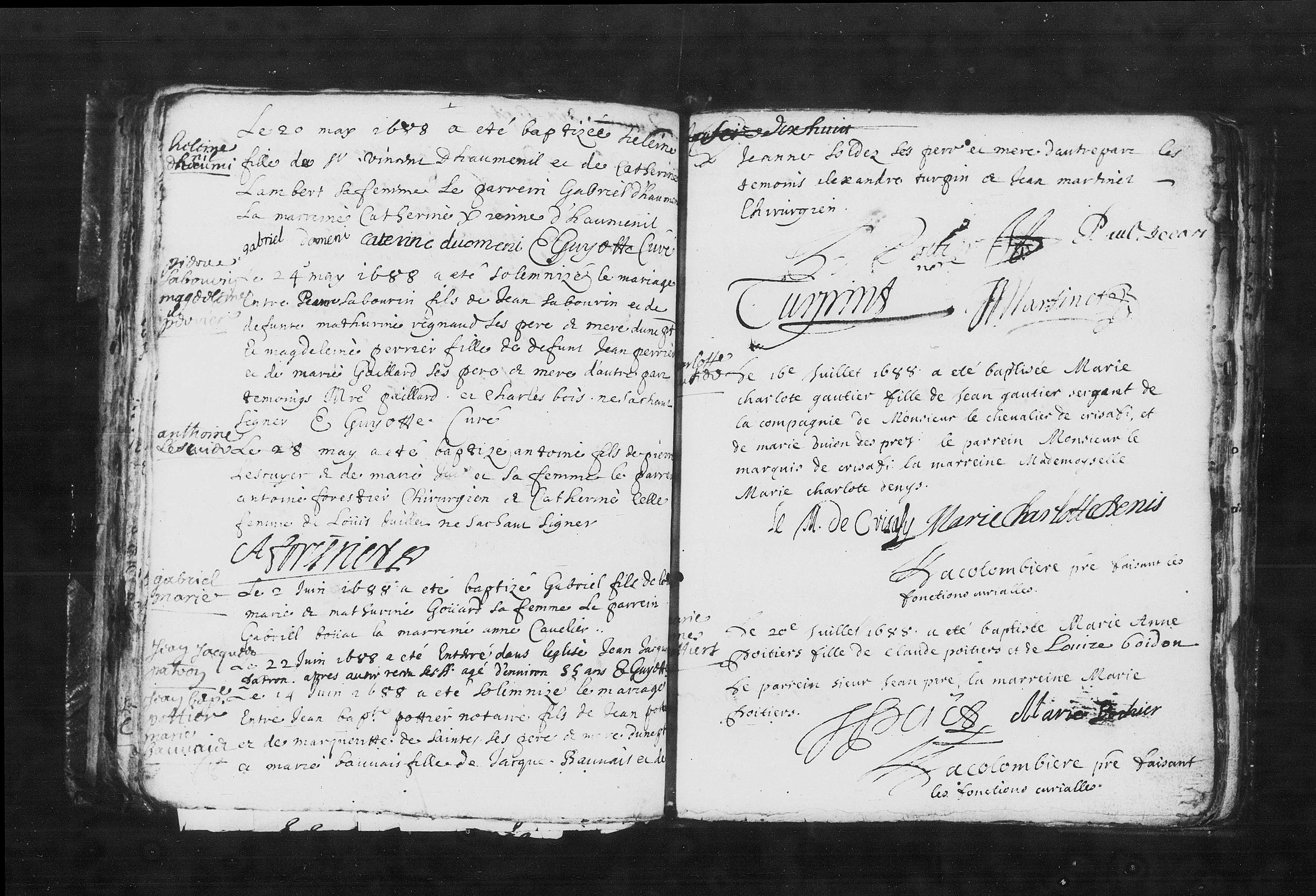

Six years after Marie merged the two households, her daughter Madeleine Perrier—then 14 years old—married her stepbrother Pierre Sabourin, approximately 22, in Notre-Dame de Montréal on May 24, 1688.

Such marriages between step-siblings were not forbidden by the Church (there was no blood relationship), and they were not unusual in blended colonial families. But this union had consequences that would echo for centuries: it permanently fused the Perrier and Sabourin bloodlines. Any descendant of Madeleine and Pierre would carry both lines—and through Marie Gaillard, would connect to both of her marriages.

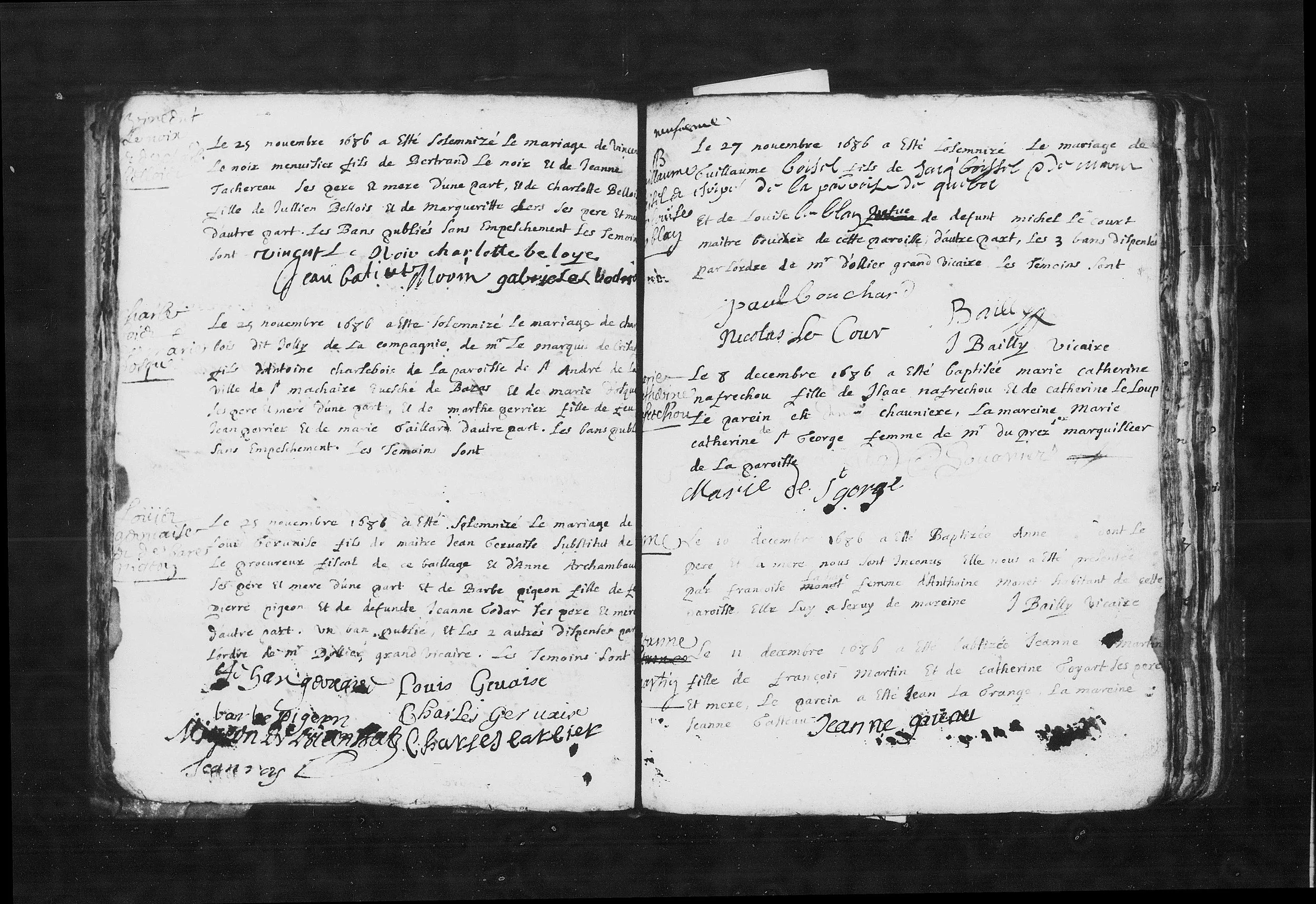

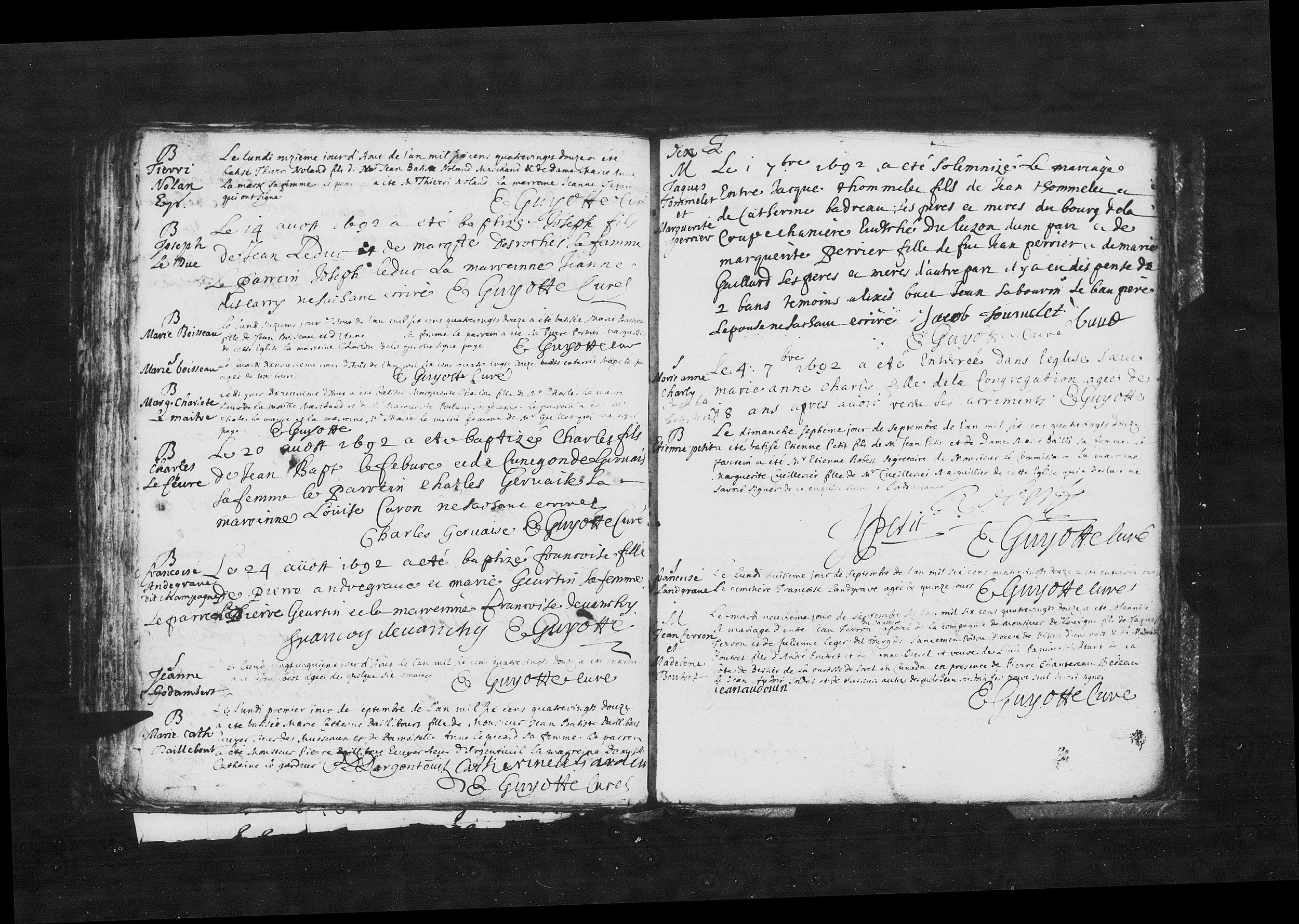

Marie's other children also married during this period: Marie to Guillaume Loret in 1683, Marthe to Jean Charlebois in 1686, Marguerite to Jacques Thomelet in 1692. Her son Jacques became a voyageur and militia captain. François Madeleine followed the fur trade routes to Mobile, Alabama. Marie had raised her children to adulthood and watched them scatter across New France—but through Madeleine's marriage to Pierre, she had also created something unusual: a single bloodline carrying forward both of her family formations.

The Montréal Years

Around 1683, Marie relocated the blended household westward to the Montréal area—a decision that placed her family closer to the expanding frontier and the opportunities it offered. Over the following decades, she and Jean Sabourin engaged in a series of land transactions that document an economically active household:

They purchased land at Rivière Saint-Pierre in 1688, acquired and surrendered a concession from the Séminaire de Saint-Sulpice, and in 1694–95 turned a 44% profit buying and selling property along Lac Saint-Pierre. By 1709, they were leasing land from the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, agreeing to clear two wooded arpents per year.

These records preserve Marie's presence in the colonial economy—her name appears alongside her husband's in notarial documents spanning more than two decades. In a legal system that subordinated wives to husbands, Marie remained visible.

The Last Fifteen Years: 1721–1736

Jean Sabourin was buried on September 28, 1721, in Pointe-Claire. He was about 80. Marie, now approximately 74, became a widow for the second time.

She did not remarry. The desperate logic that had driven her to Jean Sabourin's arms in 1682 no longer applied. Her children were grown, her grandchildren multiplying, her work in the world largely done. For fifteen more years, she lived as a widow—watching the colony transform around her, watching the children of her children's children be born.

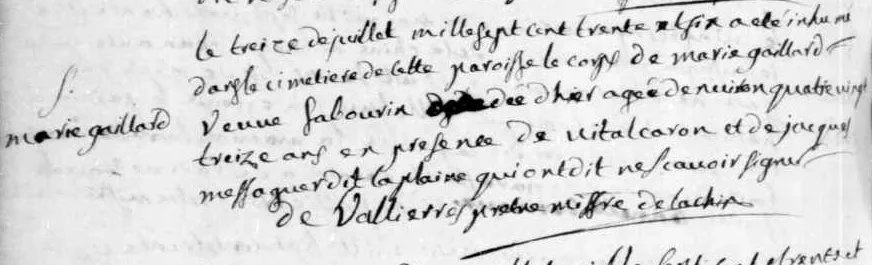

Marie Gaillard died on July 12, 1736. She was approximately 89 years old, though the priest who buried her the next day in the Saints-Anges cemetery in Lachine recorded her age as "about 93"—a common optimism in colonial records. She had outlived her first husband by 54 years, her second husband by 15. She had crossed an ocean, built and rebuilt households, merged families, and shaped a lineage.

The story of Marie Gaillard is the story of survival, adaptation, and deliberate family-building in early New France. Through endurance rather than power, she shaped a lineage that now numbers in the millions. Jean Perrier gave her children; Jean Sabourin gave her stability; but Marie herself—through her choices, her labor, and her longevity—gave her descendants their existence.

Document Gallery

Marie Gaillard's Legacy

Marie Gaillard's life spanned nearly nine decades, two marriages, eleven children raised across two households, and a lineage that would number in the millions. She left no letters, kept no diary, signed no documents. Yet through the parish records, census returns, and notarial acts that mention her name, we can trace the outlines of an extraordinary life.

She is not simply an allied ancestor to the Guilbault line—she is its matriarch on the maternal side, the woman whose survival made possible the generations that followed. Her daughter Madeleine's marriage to stepbrother Pierre Sabourin permanently bound two family formations into one. Every descendant of that union carries Marie's legacy twice over.

Note on Sources: Marie Gaillard is documented in Peter Gagné's King's Daughters and Founding Mothers (Landry 315, Dumas 212). The PRDH estimates between 1,050,000 and 1,470,000 Quebecers descend from her first marriage alone—a testament to the foundational role of the Filles du roi in populating New France, and to one woman's determination to survive.

Sources

Census Records

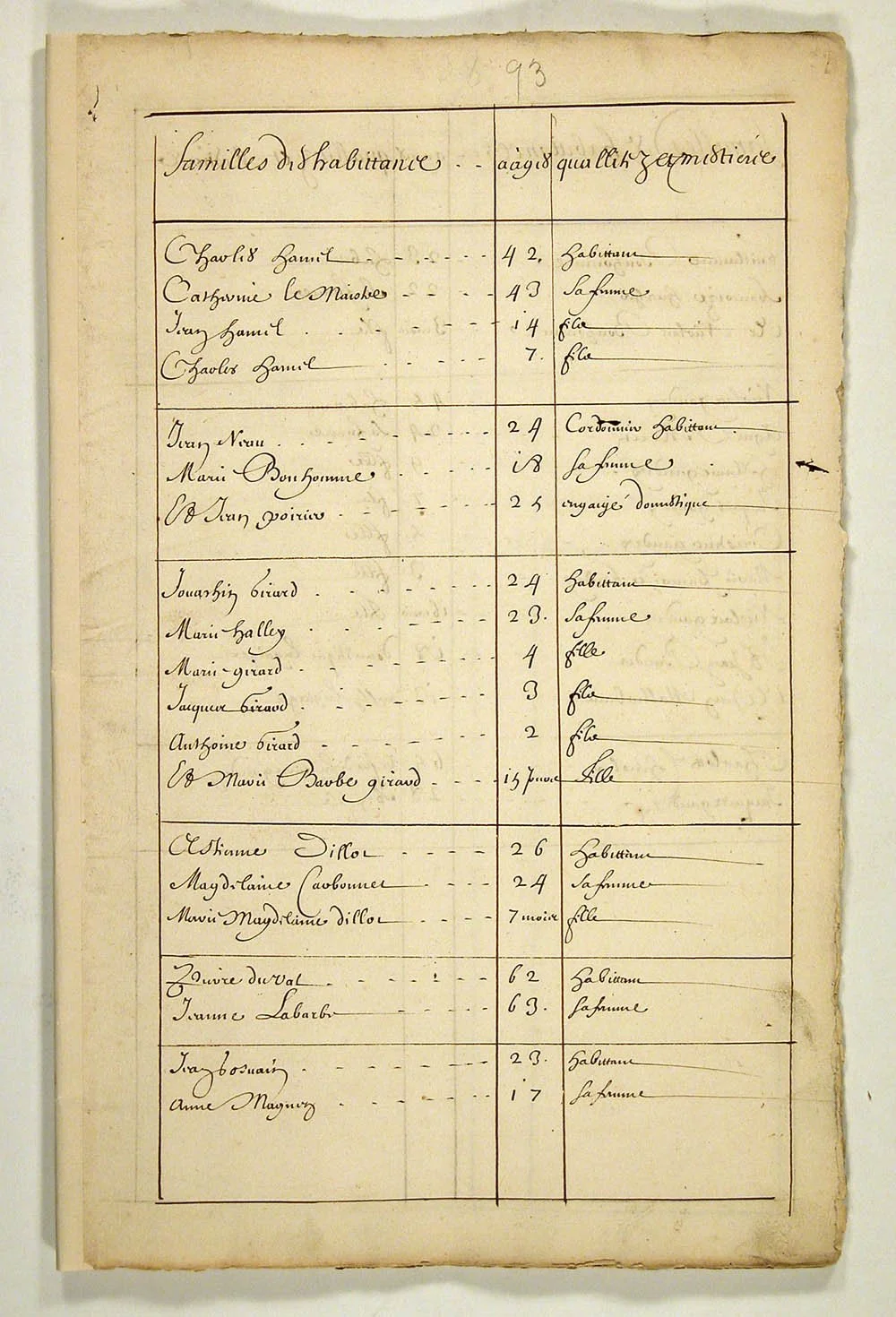

"Recensement du Canada, 1666," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/fra/accueil/notice?idnumber=2318856&app=fonandcol : accessed 26 Jan 2026), household of Jean Nau, 1666, Saint-Jean, Saint-François and Saint Michel, page 93, Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318856; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

"Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau," digital images, Library and Archives Canada (https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318858&new=-8585855146497784530 : accessed 26 Jan 2026), household of Jean Perrier, 14 Nov 1681, Beauport, image 267, Finding aid no. MSS0446, MIKAN no. 2318858; citing original data: Centre des archives d'outre-mer (France) vol. 460.

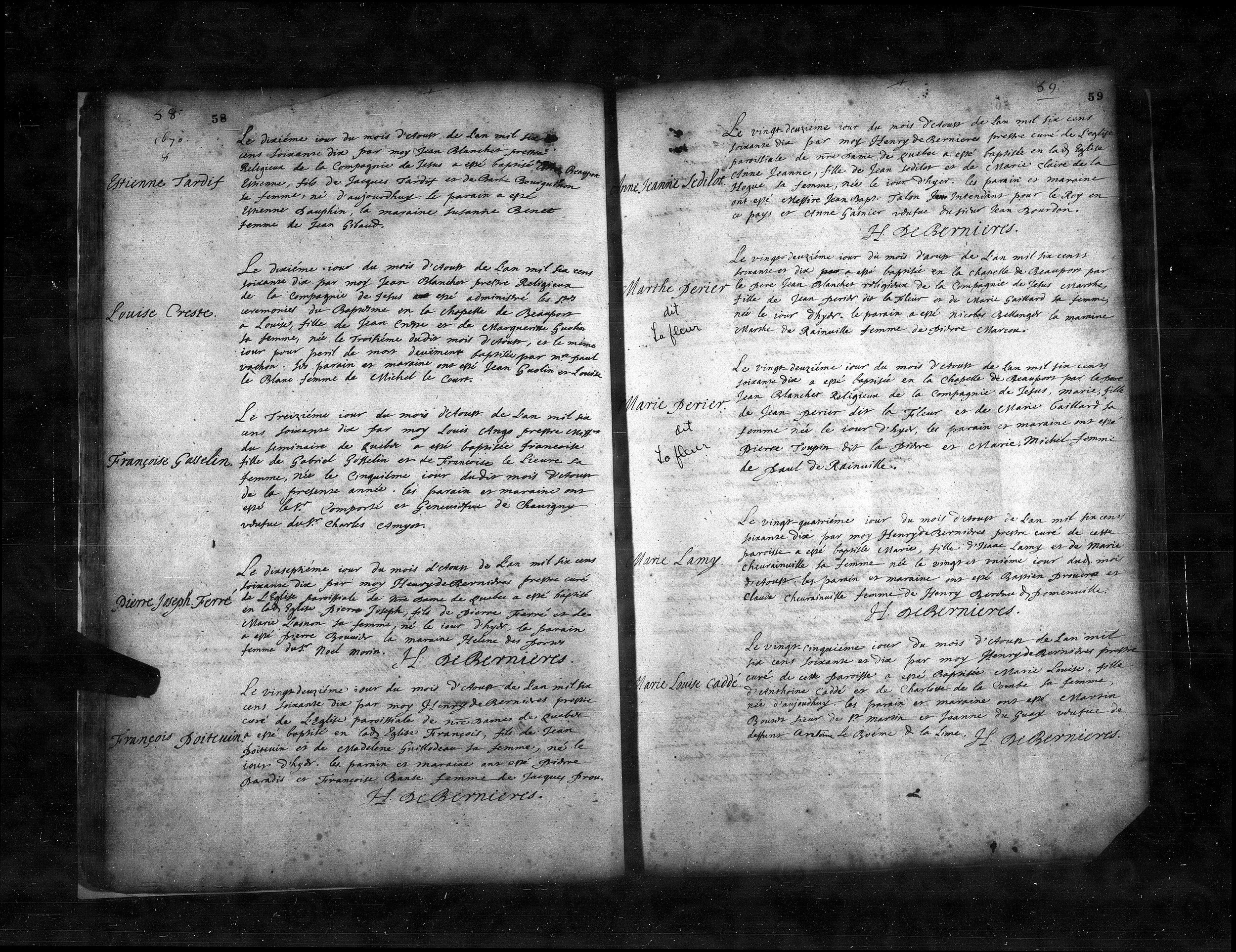

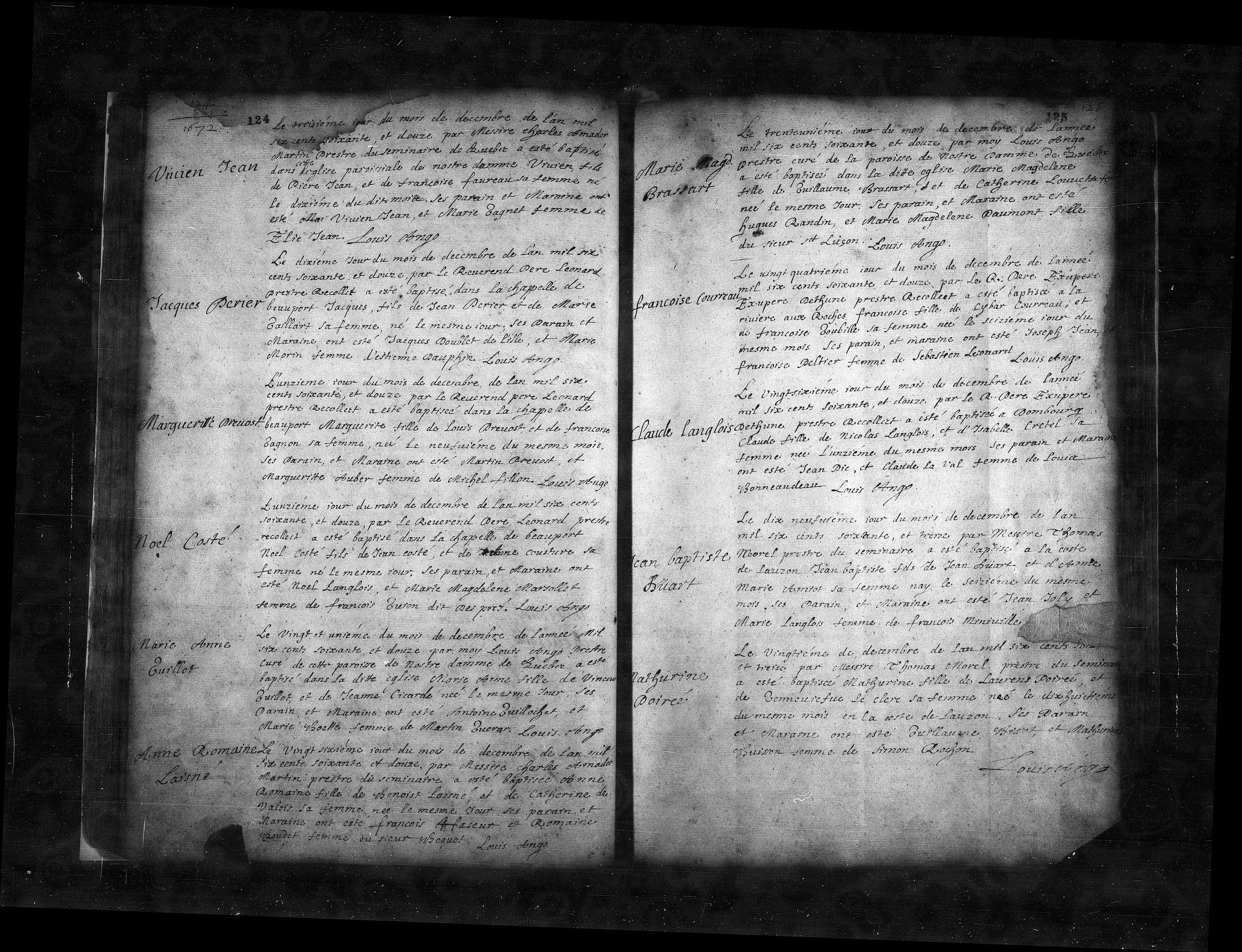

Parish Records

"Canada, Québec, registres paroissiaux catholiques, 1621-1979," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 26 Jan 2026), Notre-Dame-de-Québec, Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1621-1679; citing Archives Nationales du Québec, Montreal.

"Canada, Québec, registres paroissiaux catholiques, 1621-1979," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 26 Jan 2026), Beauport, Notre-Dame-de-la-Nativité-de-Beauport, Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1673-1674, 1678-1682, 1686, 1690, 1693-1719, 1740-1751; citing Archives Nationales du Québec, Montreal.

"Canada, Québec, registres paroissiaux catholiques, 1621-1979," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 26 Jan 2026), Lachine, Saints-Anges-de-Lachine, Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1676-1778; citing Archives Nationales du Québec, Montreal.

"Canada, Québec, registres paroissiaux catholiques, 1621-1979," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 26 Jan 2026), Montréal, Notre-Dame, Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1642-1699; citing Archives Nationales du Québec, Montreal.

"Canada, Québec, registres paroissiaux catholiques, 1621-1979," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org : accessed 26 Jan 2026), Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Sainte-Anne-du-Bout-de-l'Île, Baptêmes, mariages, sépultures 1703-1795; citing Archives Nationales du Québec, Montreal.

Notarial Records

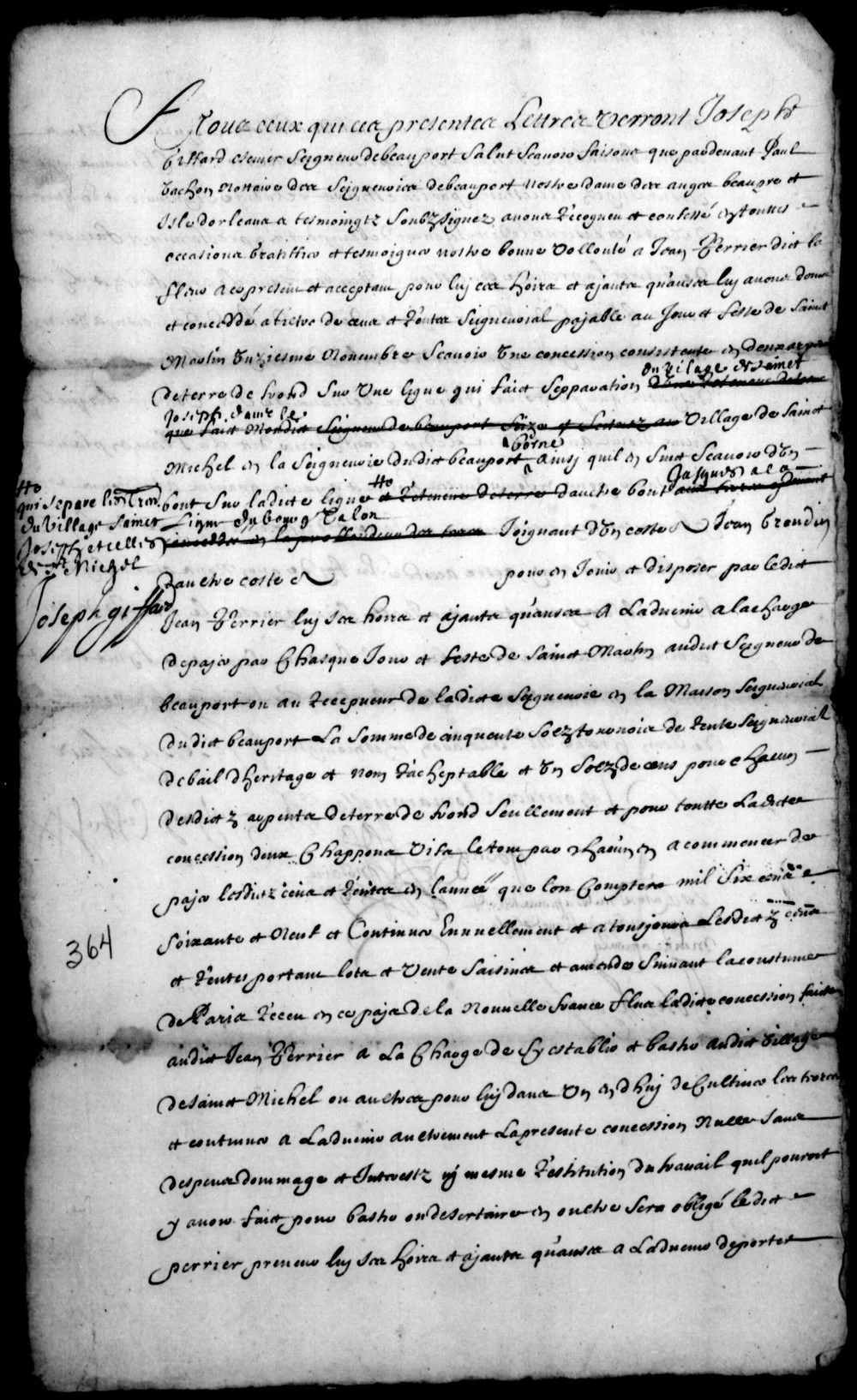

Land concession, Joseph Giffard to Jean Perrier dit Lafleur, 10 December 1668, Beauport; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

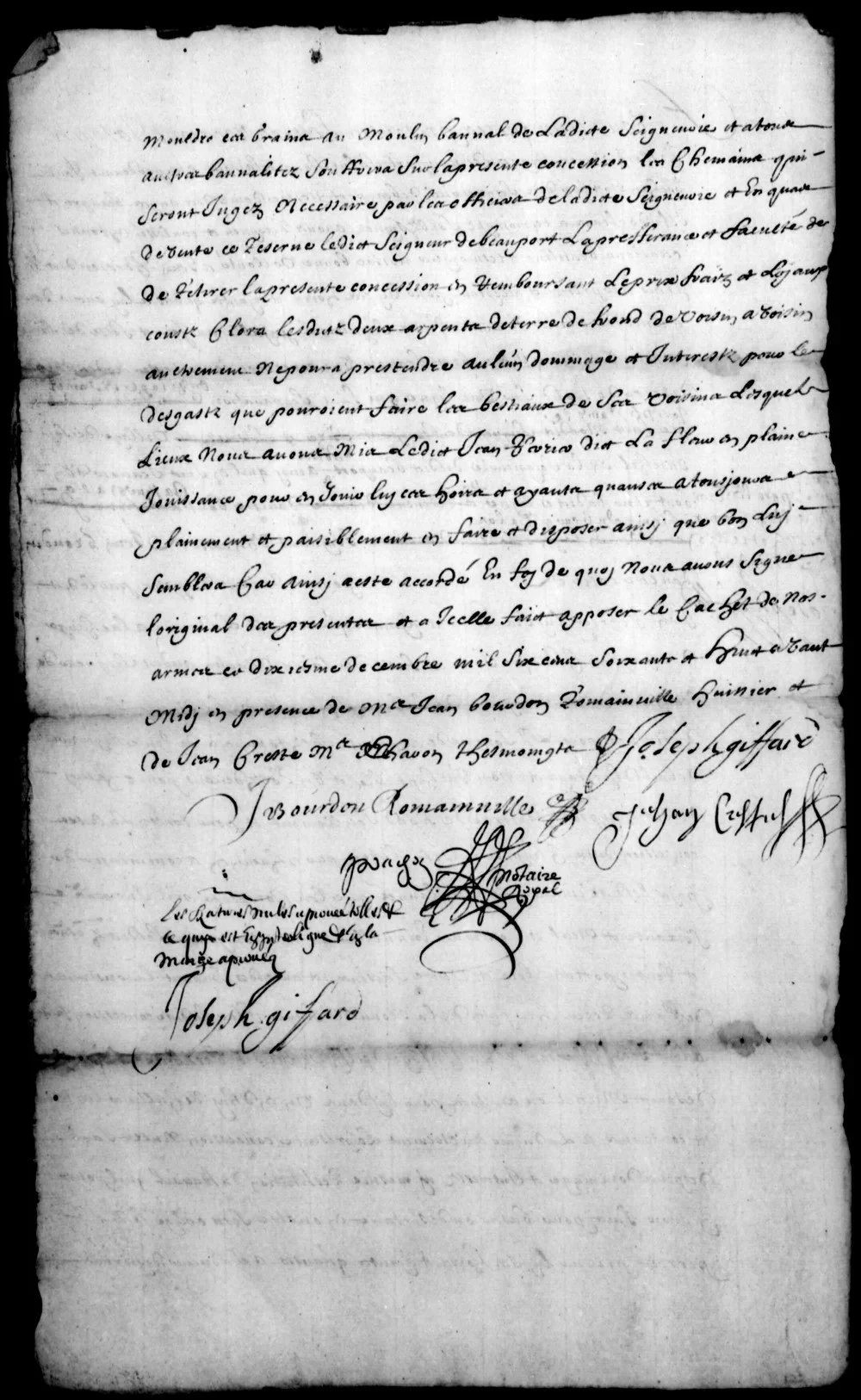

Marriage contract, Jean Sabourin and Marie Gaillard, 27 September 1684, notary Paul Vachon; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Military Records

"Roll of the Soldiers of the Regiment of Carignan Salière who became inhabitants of Canada in 1668," Library and Archives Canada.

Databases

Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH), Université de Montréal (https://www.prdh-igd.com : accessed 26 Jan 2026), couple no. 2848, Jean Perrier and Marie Gaillard; couple no. 4636, Pierre Daire and Marie Gaillard; couple no. 2849, Jean Poirier Perrier and Marie Dervie.

Fichier Origine, Fédération québécoise des sociétés de généalogie (https://www.fichierorigine.com : accessed 26 Jan 2026).

Published Sources

Gagné, Peter J. King's Daughters and Founding Mothers: The Filles du Roi, 1663-1673. Pawtucket, Rhode Island: Quintin Publications, 2001. Entry for Marie Gaillard (Landry 315, Dumas 212).

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY