Gabriel’s World: Life as a Voyageur in the Pays d'en Haut

Gabriel's World

What was it actually like to be a voyageur? To paddle 18 hours a day, carry 180 pounds across brutal portages, sleep under an overturned canoe, and spend years in the wilderness waiting to be paid? This was Gabriel Guilbault's life—and understanding it helps us understand the man behind the records.

Gabriel Guilbault

c. 1762 – 1833

The records call him "voyageur." The 1801 marriage register at Oka. The 1816 North West Company ledger. The blotters from Lac La Pluie and Athabasca. But that single word—voyageur—contained an entire world of experience that the records don't describe.

Gabriel Guilbault spent at least three decades in the fur trade, from the early 1790s through the merger of the North West Company with the Hudson's Bay Company in 1821. He was still working in the Athabasca country—one of the most remote regions in North America—when he was nearly 60 years old. To understand the man, we need to understand what that life demanded.

Frances Anne Hopkins traveled the canoe routes herself and painted what she saw with near-photographic accuracy. This is as close as we can get to seeing what Gabriel's working life looked like—the crowded canoe, the synchronized paddling, the endless water stretching ahead.

Two Kinds of Voyageurs

The fur trade companies divided their paddlers into two classes, and the distinction shaped every aspect of a man's life.

Seasonal workers who paddled the Montreal-to-Fort William route each summer. Named dismissively after their diet of salt pork and dried peas. They returned home each winter to their farms and families in the St. Lawrence valley—never venturing past Lake Superior.

Route: Montreal → Fort William

Contract: Single season

Canoe: Canots du maître (35-40 feet, 8-10 paddlers)

Multi-year contract workers who served in the interior—the pays d'en haut. Many married Indigenous women, started families, and never returned to Quebec. They became the ancestors of the Métis nation. This was Gabriel's world.

Route: Fort William → Interior posts

Contract: 3-5 years (or permanent)

Canoe: Canots du nord (25-30 feet, 5-6 paddlers)

Gabriel Guilbault was almost certainly an homme du nord. His presence in the Lake Superior region by the early 1790s, his relationship with Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe—an Ojibwe woman of the Saulteaux Nation—and his later appearances in company records at posts like Lac La Pluie (Rainy Lake) and in the Athabasca district all point to a man who made his life in the interior, far from the farms of Quebec.

"The voyageurs were the essential 'blue-collar' workers of the fur trade. They were the men who paddled, portaged, and provisioned the vast commercial network that stretched from Montreal to the Pacific."

The Work: What Gabriel Did Every Day

A voyageur's job was simple to describe and brutal to perform: transport furs and trade goods across thousands of miles of lakes, rivers, and portages. The physical demands were extraordinary—and relentless.

Charles Deas's 1846 painting The Voyageurs captures the dramatic, dangerous work of navigating rapids. The man standing at the stern, controlling the canoe with a long steering paddle, held the lives of everyone aboard in his hands. One wrong move in fast water could kill them all.

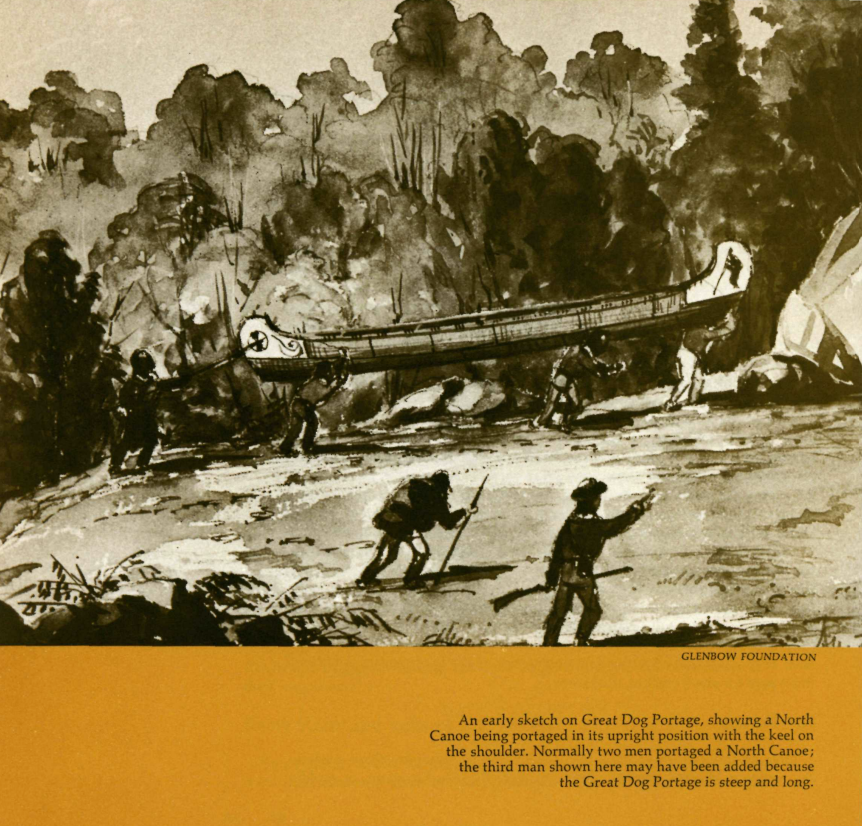

An early sketch of the Great Dog Portage shows a North Canoe being portaged in its upright position, the keel resting on the men's shoulders. Normally two men carried a canoe; the third man here may have been added because this portage—on the route Gabriel would have traveled—was steep and long. (Glenbow Foundation)

The image has become iconic: a rugged French-Canadian man wearing a red or blue tuque (knit cap), a brightly colored ceinture fléchée (arrow-head sash), moccasins, a loose linen shirt, and leather leggings. Short and compact—the canoes were cramped, and smaller men fit better. Weathered skin from years of sun and wind. Calloused hands from the paddle. And a reputation for being hardy, cheerful, and proud of work that would have broken most men.

The Contract System: Debt and Dependency

When a voyageur committed to the North West Company, he went before a notary and signed an employment contract specifying his duties, wages, and term of service. The contracts survive in archives—thousands of them—and they reveal a system that often trapped men in perpetual debt.

In 1791, it was reported that 900 North West Company employees owed the Company more than the wages of ten or fifteen years' engagement. How? Voyageurs purchased supplies on credit from Company stores at inflated prices—clothing, tools, tobacco, alcohol. The debt followed them from contract to contract. Interest accumulated. Many died still owing money. "It was common for voyageurs to wait as long as four years to receive their pay"—and by then, they often owed more than they had earned.

Gabriel's NWC account from 1816, 1820, and 1821 will likely show this pattern: wages earned on one side of the ledger, debts for goods purchased on the other. The records I've requested from the Hudson's Bay Company Archives may reveal what he bought, what he owed, and how much of his labor was his own.

The Currency of the Wilderness

The voyageurs transported trade goods west and furs east. But what exactly were they carrying? The unit of trade was the "made beaver" (MB)—equal to a prime beaver pelt or its equivalent. The price lists below were typical for the late 1700s, the very years when Gabriel was working in the trade:

What One "Made Beaver" Could Buy

These were the goods Gabriel carried in his canoe, paddled across lakes, and portaged over trails. Glass beads, gunpowder, knives, blankets, buttons—manufactured items from Britain that Indigenous traders wanted, exchanged for the beaver pelts that European markets craved. Gabriel was a link in this chain, his labor measured in beaver skins and the goods they could buy.

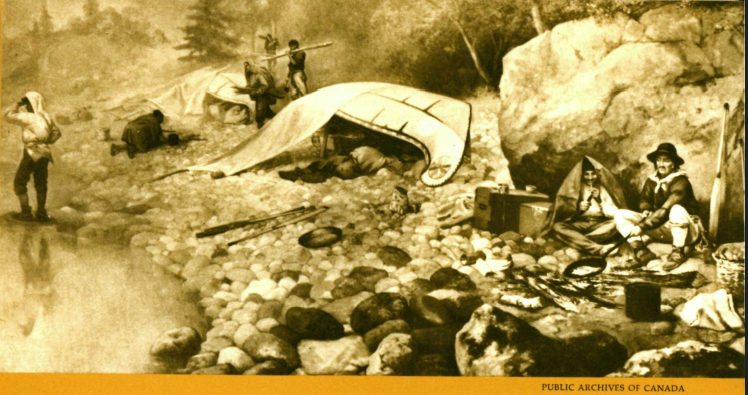

Frances Anne Hopkins's "Bivouac of a Canoe Party" shows the evening routine: wood-gathering, cooking over open fires, defense against insects, and sleeping arrangements under overturned canoes. Note the two different paddle types at right—those used by the milieux (middle paddlers) and the bouts (end paddlers). (Public Archives of Canada)

Marriage in the Pays d'en Haut

For an homme du nord like Gabriel, marriage to an Indigenous woman wasn't unusual—it was expected. These weren't casual relationships. They were marriages, recognized by Indigenous custom, essential to the trade, and productive of children, communities, and an entirely new people: the Métis.

"The first Métis were the offspring of 'country marriages' between North West Company voyageurs and traders and Indigenous women in western Canada."

Gabriel's union with Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe—an Ojibwe woman of the Saulteaux Nation on Lake Superior—followed this pattern. They lived together "à la façon du pays" for over a decade, raising at least four children before formalizing their marriage in a Catholic ceremony at Oka in January 1801.

These marriages served practical purposes too. Indigenous wives provided voyageurs with kinship connections to trading partners, knowledge of local languages and customs, and the survival skills—processing food, making and repairing clothing, maintaining equipment—that kept men alive in the wilderness. The fur trade depended on these relationships. So did Gabriel.

The Man Behind the Records

Gabriel Guilbault spent at least three decades doing this work. He paddled thousands of miles. He carried tons of cargo on his back. He slept under canoes and ate pemmican. He built a family in the wilderness and formalized it in the church. He was still laboring in Athabasca—one of the most remote places on the continent—when he was nearly 60. The records call him "voyageur." Now you know what that word meant.

Continue the Story

Baawitigong: The Place of the Rapids →

The St. Mary's River crossroads where Gabriel and Marie Josephte's worlds first met.

Abitakijikokwe: The Woman Behind the Name →

What Father Leclerc's 1801 record preserved about Marie Josephte's Ojibwe identity.

The North West Company: A Genealogist's Guide →

How to find your voyageur ancestor in the NWC records.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY