L’Annonciation d’Oka : Mission of the Lake of Two Mountains

Pointe d’Oka, Lac des Deux-Montagnes, Quebec

L'Annonciation d'Oka

For three centuries, this Sulpician mission has stood at the confluence of Indigenous and French Canadian cultures. Here, on January 27, 1801, Father Leclerc did something extraordinary: he recorded the full Ojibwe name of an Indigenous bride—Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur—preserving her identity for posterity when most priests simply wrote "Sauvagesse."

The Guilbault Family at L'Annonciation

Bride: Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe de la nation des Sauteux (baptized the day before, age ~40)

Witnesses: Nicolas Oniaragehte (Iroquois, godfather of the bride), Jaques Kaniarote (Iroquois)

Officiant: Father Leclerc

Children Legitimized: Gabriel (10 yrs 6 mos), Angélique (8 yrs), Joseph (4 yrs), François (17 mos)

After eleven years together "à la façon du pays" and four children, the couple formalized their union before the Church. The suffix "-ikwe" in her name means "woman" in Ojibwe—this was her actual Indigenous name, not a French approximation.

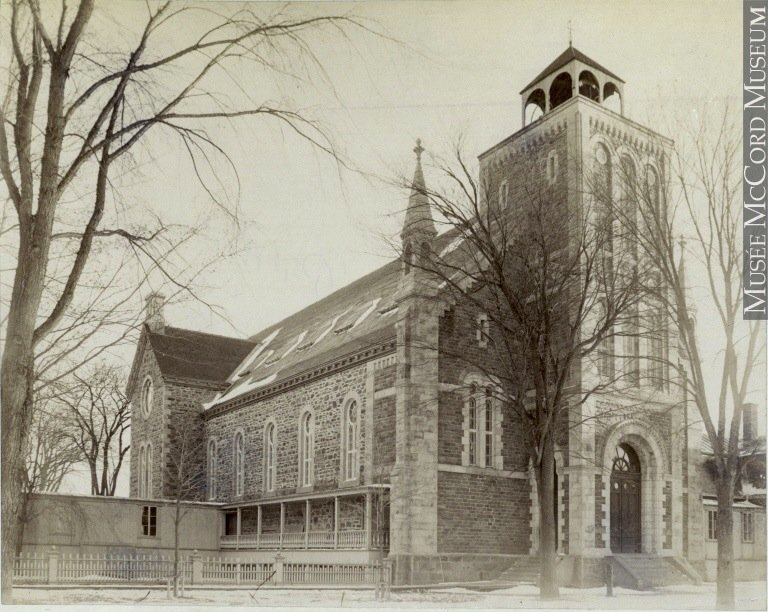

L'Annonciation Church at Oka today—this sacred place, at the confluence of Indigenous and French cultures, holds the marriage register where Marie Josephte's Ojibwe name was preserved on January 27, 1801.

When Gabriel Guilbault brought his companion of eleven years to the mission church at Oka in January 1801, he was following a path worn by countless voyageurs before him. Men of the fur trade routinely formalized their Indigenous marriages when they returned to settled life. But what Father Leclerc recorded that day was anything but routine—and it would prove invaluable to genealogists two centuries later.

The priest didn't simply write "Sauvagesse" as most would have done. He wrote her full name: Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe de la Nation Sauteuse sur le lac Supérieur. He documented her tribal affiliation. He noted her approximate age. And by doing so, he gave her descendants something precious: a name to search for, a people to claim, an identity preserved against the erasure of colonial record-keeping.

A Mission Born of Empire and Faith

In 1717, Louis XV granted the Sulpicians the Seigneury of Lac des Deux-Montagnes to establish a new mission for the Indigenous peoples of New France. By 1721, Father Maurice Quéré de Tréguron had organized a village on the lake's shores to serve Christianized Iroquoian and Algonquian peoples.

The mission served a remarkably diverse population: Mohawk and other Iroquoian peoples, Algonquin, Nipissing, and occasionally Ojibwe visitors like Marie Josephte who came from the Lake Superior region. French Canadian farmers and traders had begun settling nearby, creating the mixed community that would define Oka's character. The Sulpicians acted as both spiritual leaders and landlords (seigneurs), holding the land "in trust"—a status that would eventually lead to the Oka Crisis of 1990.

The first stone church was begun in 1728 and completed in 1732—a modest but permanent structure that would serve the community for nearly 150 years. A school, convent for the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, and residences for the Algonquian nations (to the east) and Iroquoian nations (to the west) completed the mission complex.

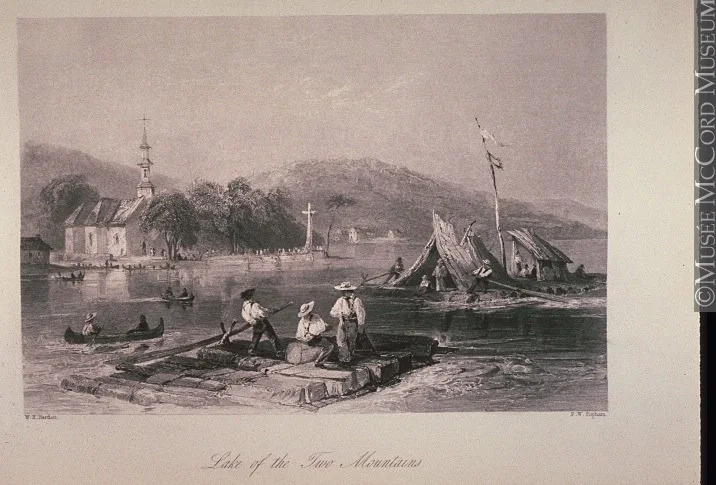

Lake of Two Mountains with the mission church visible on shore, c. 1839-1842. This view captures the setting as Gabriel and Marie Josephte's children would have known it. (McCord Museum)

The Calvary of Oka

Between 1740 and 1742, Sulpician Father Hamon Le Guen supervised construction of the famous Calvaire d'Oka—four oratories and three chapels built on the mountainside to teach the Indigenous residents about the Passion of Christ. The Sulpicians brought paintings from France, commissioned from artist Nicolas Lefebvre, continuing a medieval tradition of using images to convey Christian teachings.

"One does not make the journey to Lake of Two Mountains just to see the canvases contained in the church of this mission [...], they are indeed the finest paintings that Canada possesses."

These paintings—replicas of works by Rubens, Jouvenet, and other European masters—were moved inside the church around 1776. When fire destroyed the building in 1877, they were "miraculously" saved and today hang in the nave of the current church—the same works that would have witnessed Gabriel and Marie Josephte's marriage in 1801.

Timeline: The Mission Through the Centuries

January 27, 1801: A Name Preserved

After eleven years together and four children, Gabriel Guilbault and the woman known only as "Josephte Sauvagesse" traveled to L'Annonciation at Oka to formalize their union before the Catholic Church. What happened in the mission church that January would prove extraordinary—and genealogically priceless.

The Name the Priest Preserved

On January 26, 1801, Father Leclerc baptized the bride and recorded her full Ojibwe name:

The suffix "-ikwe" means "woman" in Ojibwe. This was her actual Indigenous name, not a French approximation—proof that Father Leclerc took the time to record her identity accurately.

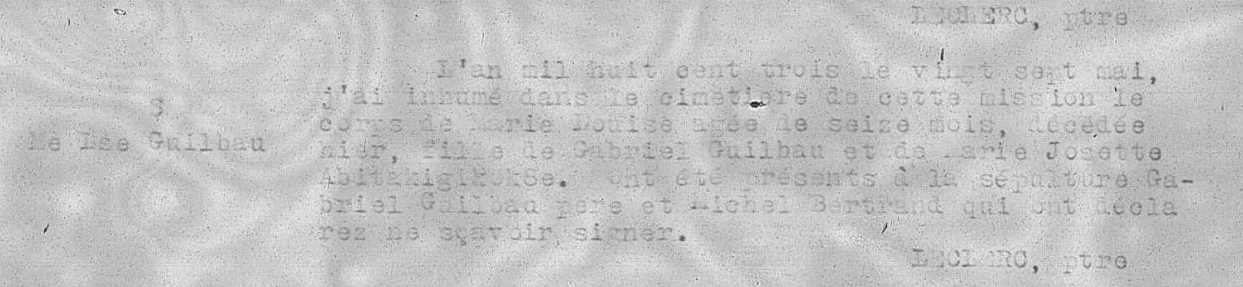

Original handwritten register page, L'Annonciation, Oka, January 1801. The entries record first her baptism as "Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe de la Nation Sauteuse," then the marriage with legitimization of four children.

Gabriel Guilbau & Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe

Groom: Gabriel Guilbau, voyageur

Bride: Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe de la nation des Sauteux

Witnesses: Nicolas Oniaragehte (Iroquois, godfather of the bride), Jaques Kaniarote (Iroquois)

Children Legitimized: Gabriel (10 yrs 6 mos), Angélique (8 yrs), Joseph (4 yrs), François (17 mos)

The marriage witnesses reveal the multicultural nature of the Oka mission. Marie Josephte's godparents were both Iroquois: Nicolas Oniaragehte and Anne Satioksen. Her marriage witnesses—Nicolas Oniaragehte again, and Jaques Kaniarote—were also Iroquois of the Oka mission. An Ojibwe woman from Lake Superior, sponsored by Iroquois Catholics, marrying a French Canadian voyageur: this was the reality of the fur trade world.

The Guilbault Family at Oka

The family's connection to Oka extended beyond the January 1801 marriage. Parish registers document both the joys and sorrows of their life at the mission—including the deaths of two young children within two years of their arrival.

Burial of François Guilbault, April 4, 1801. Mother listed as "Marie Josephe Abitakijikokwe." Present at the burial: Gabriel Guilbau (uncle) and Catherine Nesepik8e—another Indigenous woman whose name was preserved.

The parish records track Gabriel's transition from the fur trade to settled life. In the 1801 marriage record, he is listed as "voyageur"—still connected to the canoe routes and trading posts. But by Marie Louise's baptism in January 1802, he is recorded as "maçon" (mason)—a tradesman building permanent structures rather than paddling furs to market. The couple would eventually settle near Rigaud, where Marie Josephte died and was buried in 1813.

Destruction and Resurrection

On June 15, 1877, fire destroyed the 150-year-old church at Oka along with the rectory and several nearby buildings. The conflagration came during a period of intense tension between the Sulpicians and the Mohawk community over land rights—tensions that would erupt again over a century later in the Oka Crisis of 1990.

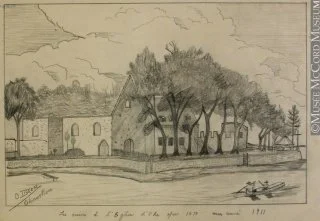

The church at Oka as it appeared in 1872, just five years before the fire—the closest visual record we have to the building where the 1801 marriage took place. Drawing by Oheroskon Dicaire. (McCord Museum)

Four days after the fire, twelve Mohawk men including Joseph Onasakenrat and his father were arrested and charged with depredation. Construction of the present church began in 1879 under architects Maurice Perreault and Albert Mesnard, who designed a building in the "modern Romano-Byzantine" style with striking contrasts between pinkish and paler stones.

Then & Now

The 80-foot bell tower, completed in 1907, houses three bells—two cast in 1884 and the largest in 1886. A chapel dedicated to Kateri Tekakwitha was built between 1907 and 1909, honoring the devout Iroquois woman (1656-1680) who became the first Native American saint in 2012.

The Shrine Today

View of the choir, 2017. The interior was redesigned by artist Guido Nincheri in 1932, but the 18th-century paintings that survived the 1877 fire—works that would have hung in the church when Gabriel and Marie Josephte married—still grace the nave.

Designated as part of the Oka heritage site by the Quebec government in 2001, the Church of the Annunciation continues to draw visitors who come to see its remarkable collection of 18th-century paintings and experience the unique atmosphere of this place where Indigenous and French Canadian histories intertwine.

"It is most pleasing, by the water's edge and in the foliage of the tall trees... one of the few sites to offer a symbiosis between history, culture and nature."

Visiting the Site

Address: 181 Rue des Anges, Oka, Quebec

Tours: Guided historical tours available during summer months through the parish council of Saint-François d'Assise

Features: 18th-century paintings by Nicolas Lefebvre, silver pieces presented by Louis XV in 1749, and the Kateri Tekakwitha Chapel

Document Gallery

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY