Jean Perrier dit Lafleur: Soldier of the Islands, Settler of Beauport

Jean Perrier dit Lafleur

He sailed from La Rochelle to the Caribbean, survived the siege of Cayenne, built forts along the Richelieu, and chose to stay in New France when his regiment went home. He died at thirty-five, leaving behind a widow and five young children—and a lineage that would number over a million descendants.

A Soldier from Béarn

Jean Perrier was born around 1646 in Pau, the capital of Béarn in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques. Located in southwestern France just fifty kilometres north of the Spanish border, Pau sat at the foot of the mountains, dominated by the château where Henri IV had been born a century earlier. Jean's father, also named Jean Perrier, worked as a maître-tisserand—a master weaver. In seventeenth-century France, it was common for sons to follow their fathers' trades, but the younger Jean chose a different path.

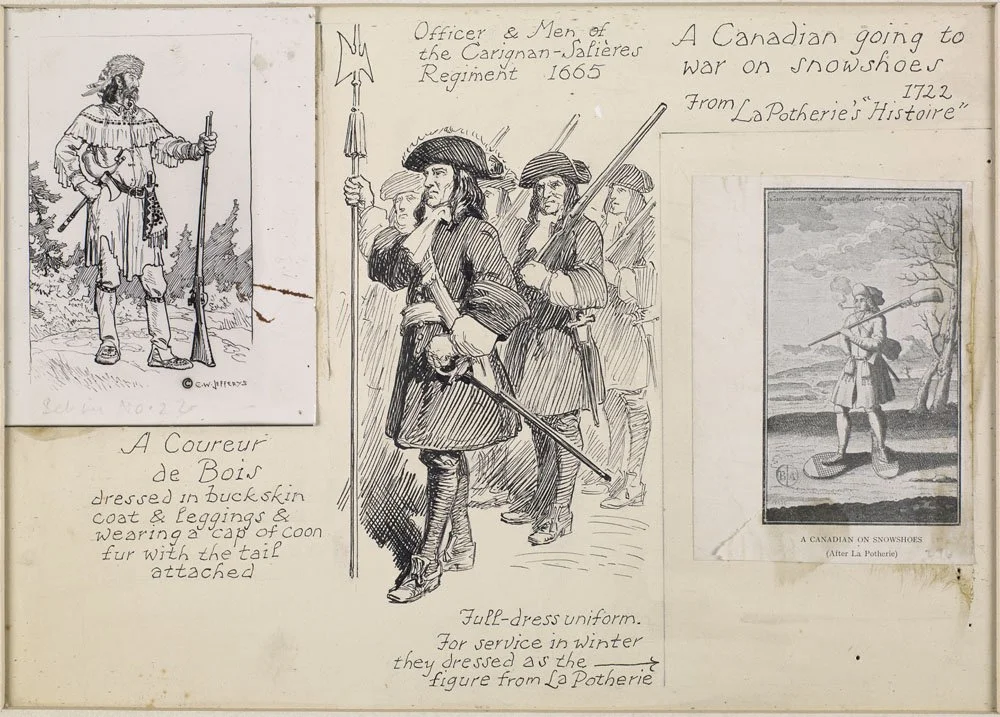

For a nineteen-year-old son of a master weaver, joining the army was a way to see the world and eventually gain economic independence through free land—something virtually impossible to achieve back home in Béarn. Around 1664, Jean enlisted in the Régiment d'Orléans as an infantry soldier, assigned to the company of Captain Vincent de la Brisardière. It was a decision that would take him across two oceans and three continents before he was thirty years old.

Like most soldiers of his era, Jean acquired a dit name—a nickname that would distinguish him from the dozens of other Perriers and Poiriers in the ranks. His was "Lafleur," meaning "the flower." It was the most common nom de guerre among French soldiers, used by approximately seventy different men who served in Canada during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In France, these names were rarely inherited. In New France, they would become permanent family surnames. Jean likely acquired his dit name during the Caribbean expedition of 1664, when his company was detached for special service under the Marquis de Tracy.

Key Facts: Jean Perrier dit Lafleur

The Caribbean Expedition (1664)

The La Brisardière Company was initially part of the Régiment d'Orléans, but in 1663–1664, it became one of four detached companies selected to serve under Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy, the newly appointed Lieutenant-General of French America. The other three companies were Berthier, La Durantaye, and Monteil. Together, these four companies would form a special expeditionary force with a mission to re-establish French control across the Americas.

On February 26, 1664, Jean's company boarded the man-of-war Brézé at La Rochelle. The 800-ton warship, commanded by Captain Job Forant, carried the four companies under Tracy's command. Their first objective: to drive out the Dutch and secure French interests across the Caribbean.

The voyage took them first to Cayenne, on the northern coast of South America. In May 1664, Tracy's forces successfully recaptured the settlement from the Dutch, installing a French governor and settling 650 new colonists. From there, the flotilla moved through the Caribbean, consolidating French control in Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Grenada.

The Caribbean was brutal. Tropical disease killed more soldiers than combat ever did. Those who survived the fevers, the dysentery, and the hurricanes emerged hardened veterans. When orders came in early 1665 to proceed to New France, the men of the La Brisardière Company had already proven themselves in conditions far worse than anything the St. Lawrence winter could offer.

The Iroquois Campaign (1665–1667)

The Brézé arrived at Quebec on June 30, 1665, carrying Tracy and the four companies that had served in the Caribbean. They joined the main body of the Carignan-Salières Regiment, which had arrived separately. Although Jean's company was never formally integrated into the Carignan-Salières, they served under the same command structure and carried out the same mission. In total, the combined force comprised twenty-four companies and approximately 1,200 men—the largest military force New France had ever seen.

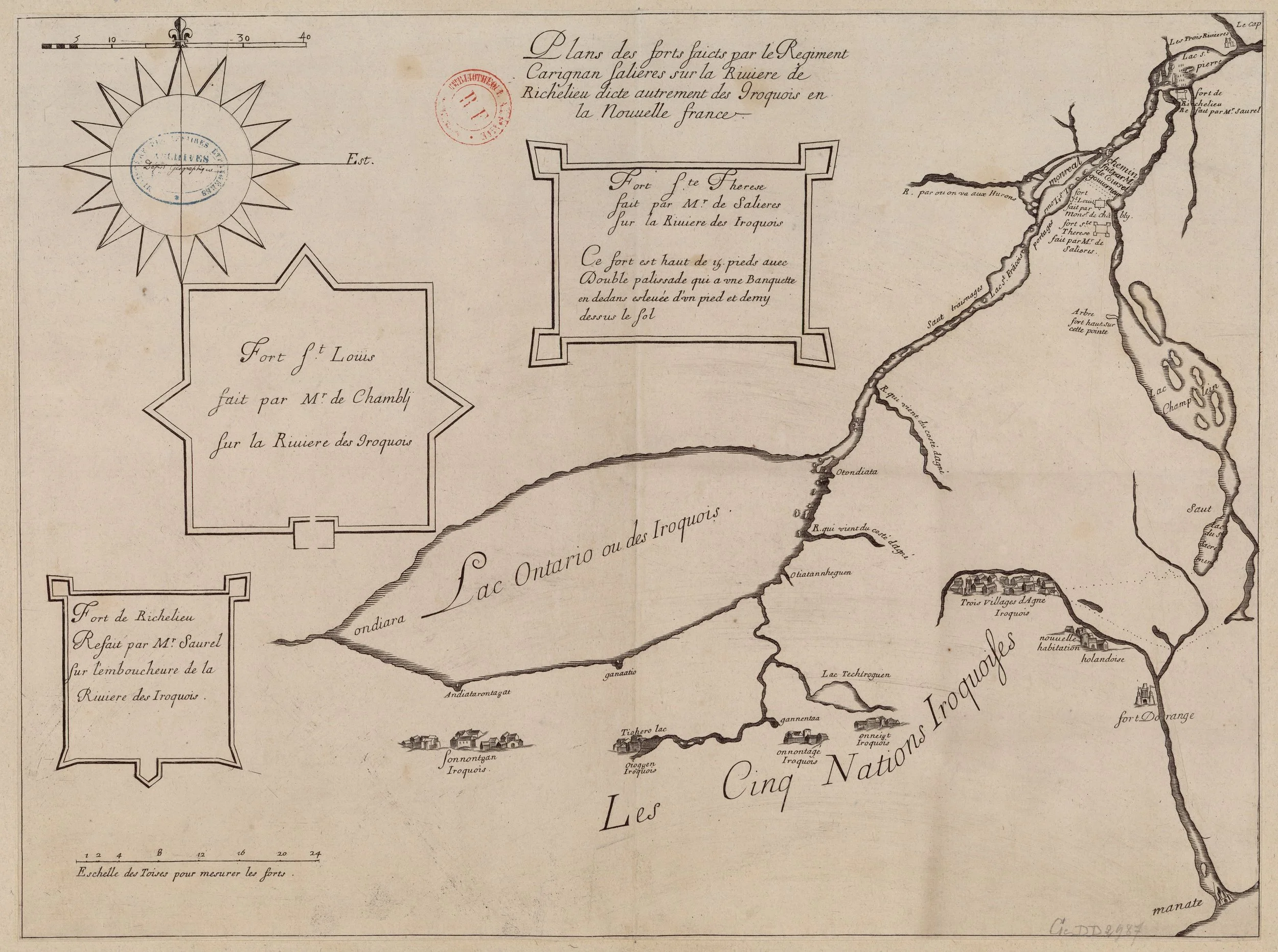

Their mission was to end the Iroquois threat that had paralyzed the colony for decades. The Five Nations—Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca—had been conducting raids that disrupted the fur trade and terrorized French settlements. The colonists had been begging for military protection for years.

The combined forces built a chain of forts along the Richelieu River, the traditional invasion route from Iroquois territory. Fort Richelieu at the river's mouth. Fort Saint-Louis (later known as Fort Chambly) further upstream. Fort Sainte-Thérèse, a fifteen-foot-high double palisade designed by the Marquis de Salières himself. Fort Saint-Jean, blocking the route to Lake Champlain. These fortifications would transform the military geography of New France.

The La Brisardière, Berthier, La Durantaye, and Monteil companies—the four that had served in the Caribbean—were exempted from fort construction during the winter of 1665-1666. They had already done their service in the islands. But Jean and his companions participated in the subsequent campaigns against the Mohawk villages in 1666, which finally brought the Iroquois to the negotiating table.

From Soldier to Settler (1666–1668)

When the campaign ended, King Louis XIV offered the soldiers a choice: return to France with the regiment, or remain in Canada as settlers. The crown sweetened the offer with land grants, seed money, and supplies. Of the 1,200 men who had come to fight the Iroquois, approximately 400 chose to stay.

Jean Perrier was one of them.

The transition from soldier to settler was not immediate. In the 1666 census, Jean appears not as a landowner but as an engagé domestique—an indentured servant—in the household of Jean Nault near Quebec City. This was common practice for soldiers awaiting formal discharge and land grants. They worked for established colonists while learning the skills they would need to survive on their own.

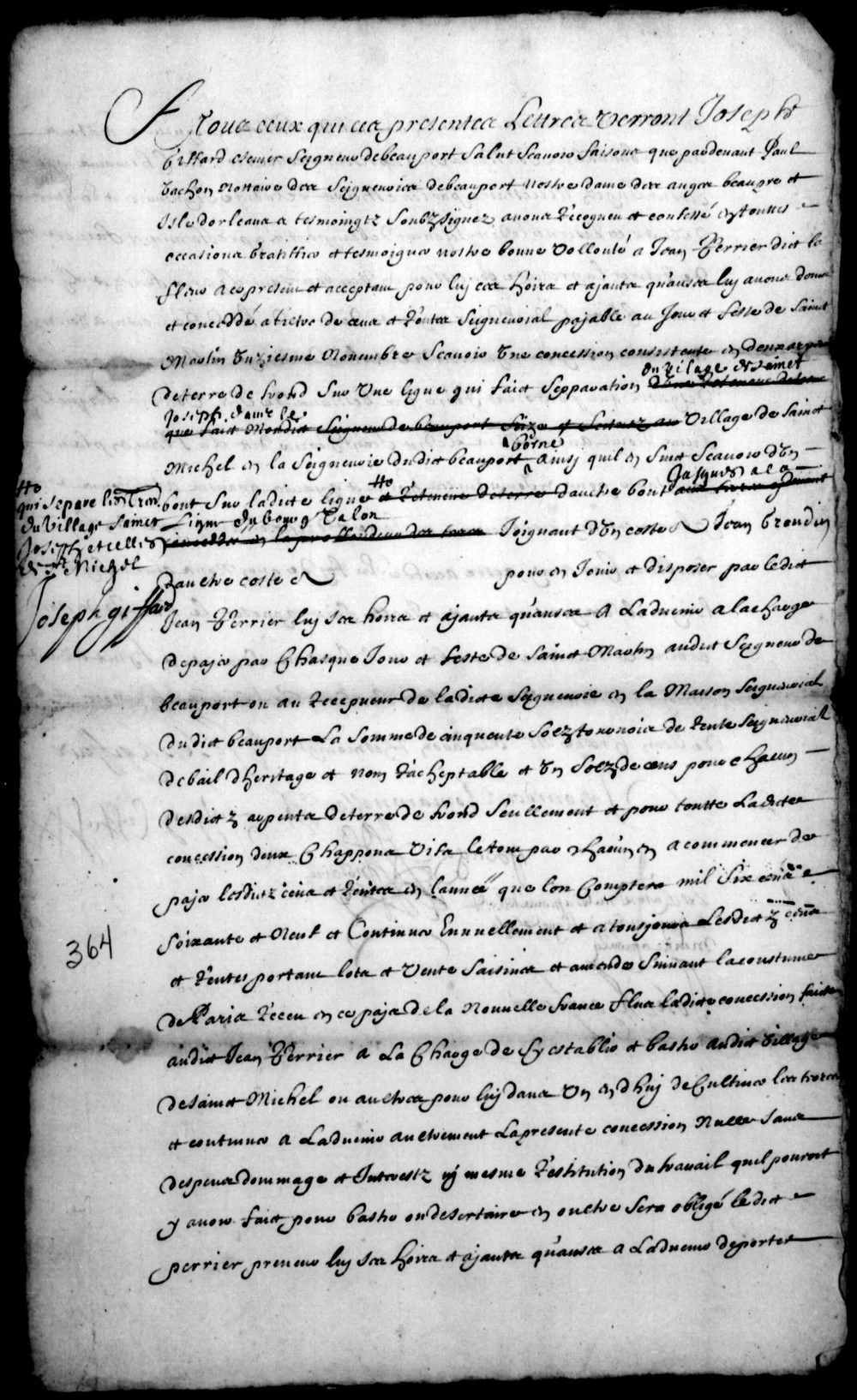

On December 10, 1668, Jean formally became a habitant. Seigneur Joseph Giffard granted him a concession in Beauport, located between the villages of Saint-Joseph and Saint-Michel. The land came with obligations: annual rent to the seigneur, the duty to clear and cultivate the soil, the requirement to grind grain at the seigneurial mill. But it also came with something Jean had never possessed in France: ownership of his own piece of earth.

Marriage to a Fille du Roi (1669)

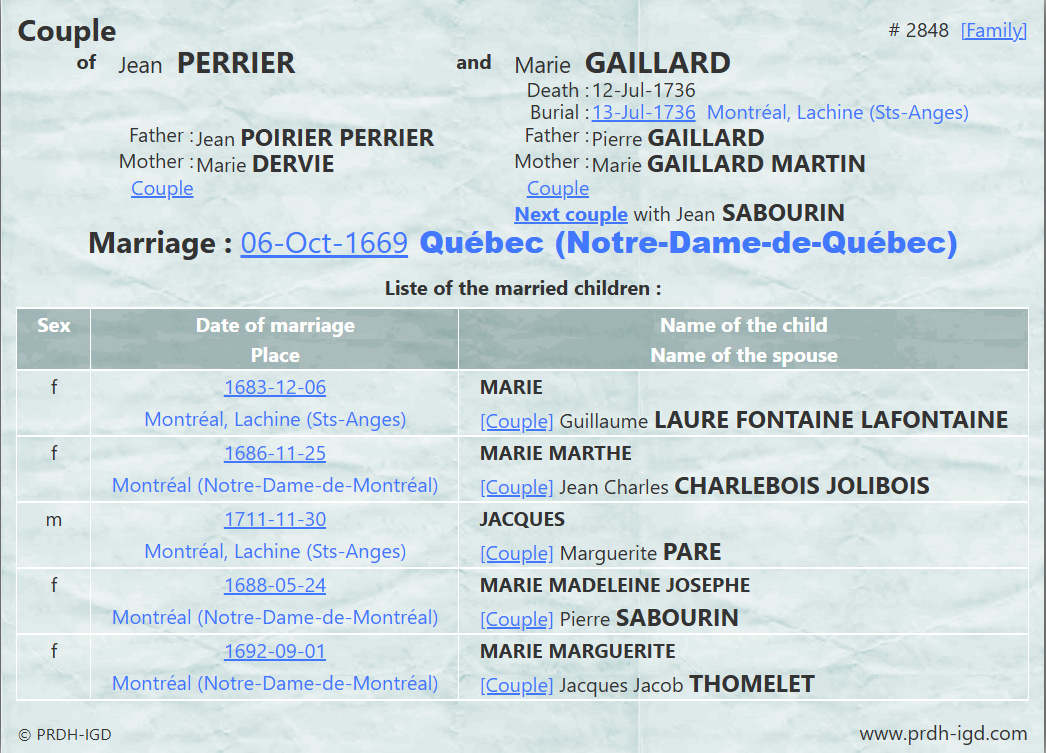

A farm needed a wife. In 1669, the ships from France brought a new cohort of Filles du Roi—the King's Daughters, young women sponsored by Louis XIV to marry the surplus of single men in the colony. Among them was Marie Gaillard, a twenty-two-year-old from Rouen in Normandy.

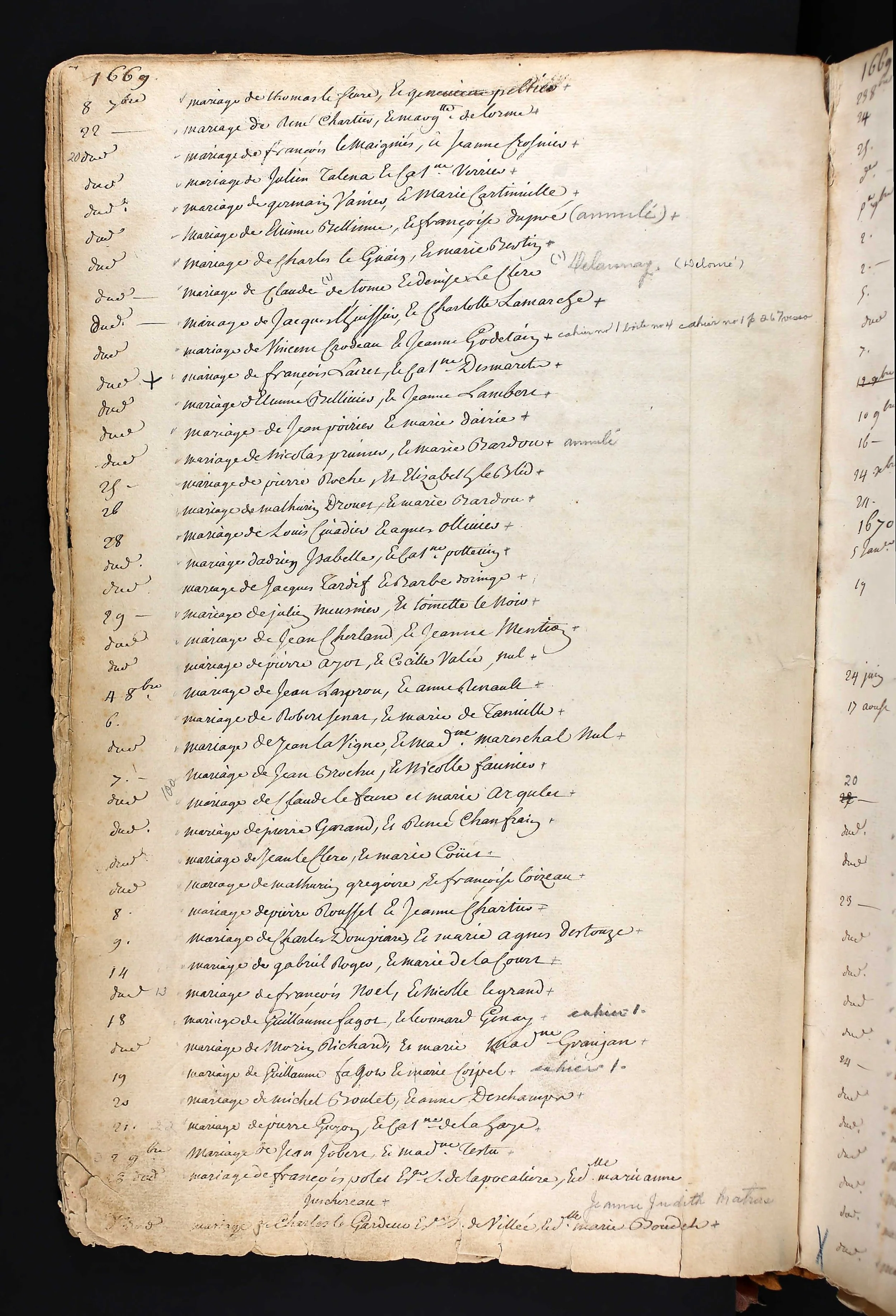

Jean and Marie's marriage contract was signed on September 22, 1669, before notary Romain Becquet in Quebec City. The document records the standard provisions: mutual gifts of property in case of death, the bride's dowry (provided by the King), the groom's commitment to establish a household. Two weeks later, on October 6, they were married in the church at Quebec.

The marriage register records the union of "Jean Poirier" and "Marie Daire"—the variants in spelling that make colonial genealogy so challenging. But the notarial records are clear: this was Jean Perrier dit Lafleur, soldier of the La Brisardière Company, and Marie Gaillard, Fille du Roi.

How Jean Perrier Connects to the Guilbault Line

8th ggf → Madeleine Perrier

m. Pierre Sabourin → Pierre Sabourin Jr.

m. M-Anne Bourdon → Marie Sabourin

m. Louis LaRocque → Joseph LaRocque

4th ggf → M. Madeleine Laroque

m. Gabriel Guilbault fils

Building a Household: Beauport (1669–1681)

The Perrier household in Beauport grew quickly. Between 1670 and 1680, Marie gave birth to seven children:

The Children of Jean Perrier and Marie Gaillard

Seven children born in Beauport between 1670 and 1680

1. Marie Perrier

2. Marie Marthe Perrier

3. Jacques Perrier

4. Jean Perrier

5. Marie Madeleine Perrier

6. Marguerite Perrier

7. François Madeleine Perrier

The 1681 census paints a picture of a struggling household. Jean is listed as a farmer in Beauport with his wife and five children. The family possessed one gun, two horned cattle, and had cleared only four arpents of land. Compare this to the more prosperous farms in the area—some had ten or fifteen arpents under cultivation—and it becomes clear that the Perrier family was barely surviving.

For a soldier who had fought in the Caribbean and helped build the chain of forts that secured New France, the return on his investment was meager. Beauport's rocky soil yielded grudgingly. The short growing season left little margin for error. And Jean, trained for war rather than farming, may have lacked the skills that lifelong habitants had learned from childhood.

A Sudden Death (1682)

Jean Perrier dit Lafleur died sometime between November 14, 1681—when he appeared in the census—and September 22, 1682—when his widow Marie remarried. He was approximately thirty-five years old.

No burial record has ever been found. This was not unusual in seventeenth-century New France. If a man died suddenly in a remote area, or during a season when travel to the parish church was difficult, the body might be buried without formal ecclesiastical registration. The absence of a record does not mean the death went unwitnessed—only that no priest was present to document it.

What the records do show is the aftermath. Marie Gaillard, widowed at thirty-five with five children under twelve, did what colonial widows had to do: she remarried quickly. On September 22, 1682—exactly thirteen years to the day after her first marriage contract—she signed a new contract with Jean-Baptiste Sabourin, a ploughman from Poitou. Within days, they were married.

Legacy

Jean Perrier lived in New France for only seventeen years. He died young, leaving a struggling farm and a widow with five small children. By most measures, his life was ordinary—one of hundreds of soldiers who chose to stay when the regiment went home, one of thousands of habitants who scratched a living from the Canadian soil.

But the descendants of that ordinary life are extraordinary in number. According to the PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique), Jean Perrier and Marie Gaillard's union produced between 1,050,000 and 1,470,000 descendants in Quebec alone—making them among the most prolific founding couples in French Canadian history.

The Perrier name survives. The Lafleur name survives. And the bloodline that began with a soldier from Béarn and a Fille du Roi from Normandy runs through millions of French Canadians and Franco-Americans today.

Timeline

Primary Sources

The documents that tell Jean Perrier's story—from military rolls to parish registers to notarial records.

Sources

Census Records

- 1666 Census of New France. Library and Archives Canada. Jean Perrier listed as engagé domestique in household of Jean Nault.

- 1681 Census of New France. Library and Archives Canada. Jean Perrier, farmer, Beauport: wife, 5 children, 1 gun, 2 horned cattle, 4 arpents.

Military Records

- Roll of the Soldiers of the Regiment of Carignan-Salières who became inhabitants of Canada in 1668. Library and Archives Canada. "Perrier, Jean; dit LaFleur; Regiment: La Brisandière."

- Carignan-Salières Regiment Official Records. Companies: La Brisardière (Orléans), Berthier (Allier), La Durantaye (Chambellé), Monteil (Poitou) under Marquis de Tracy.

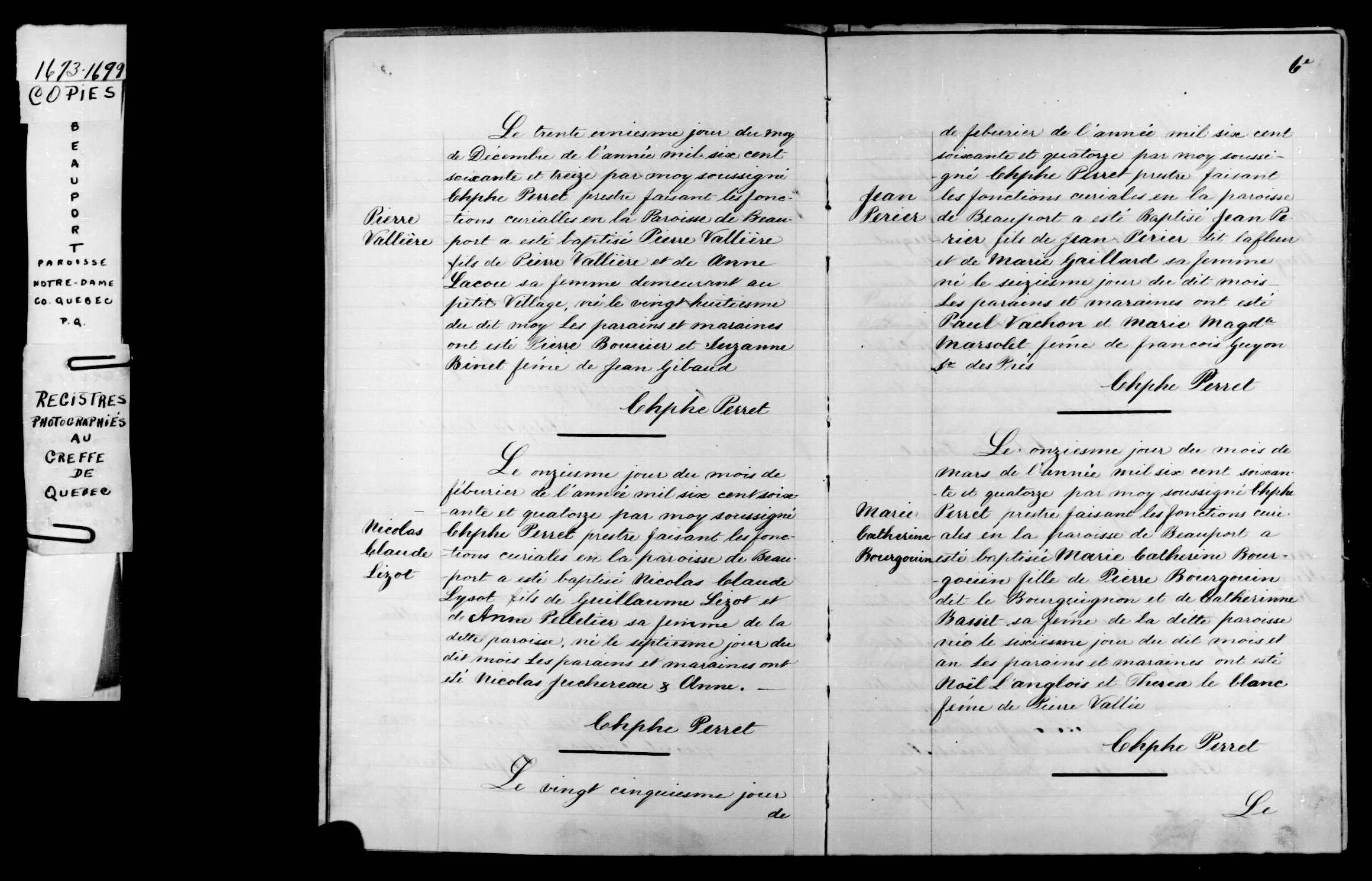

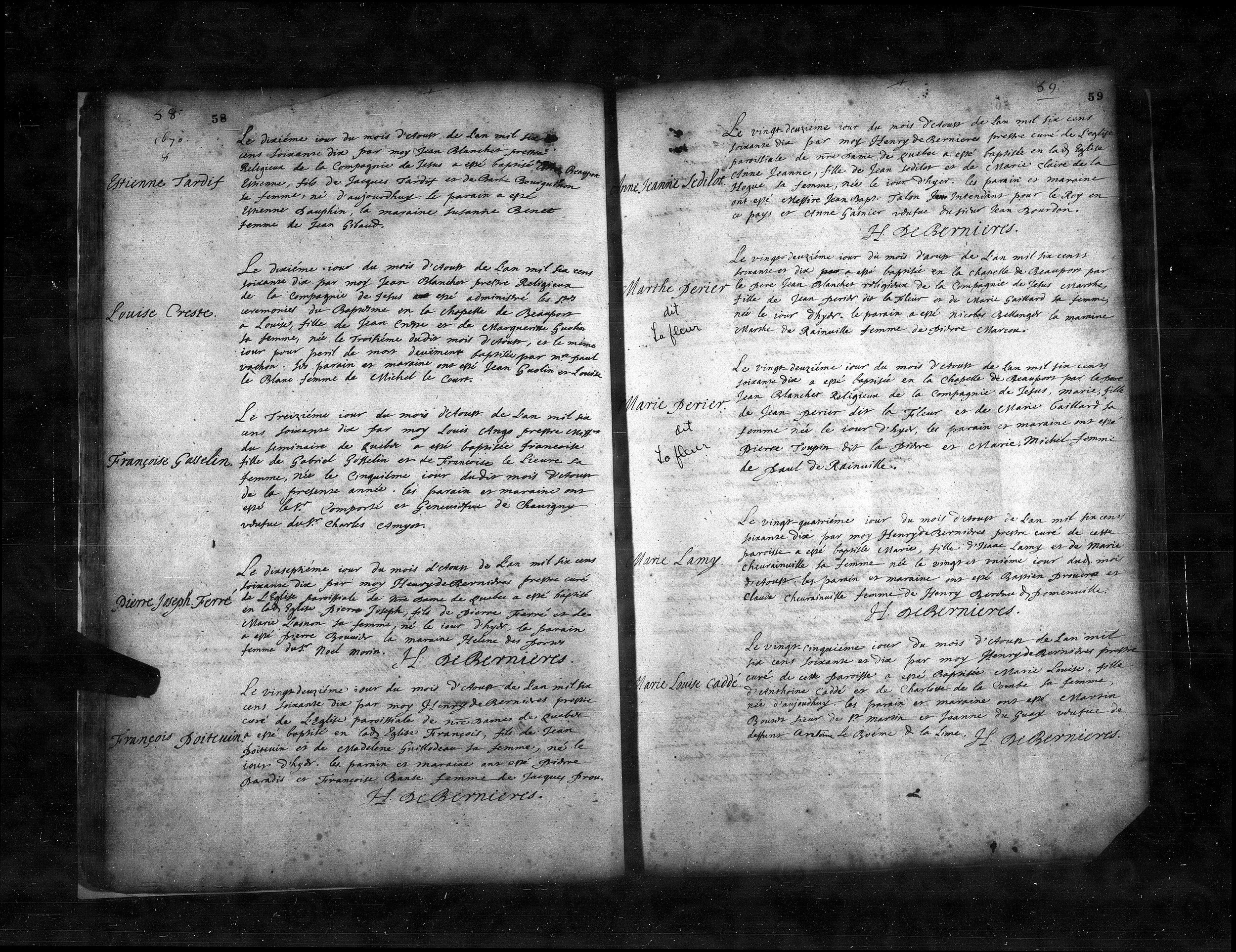

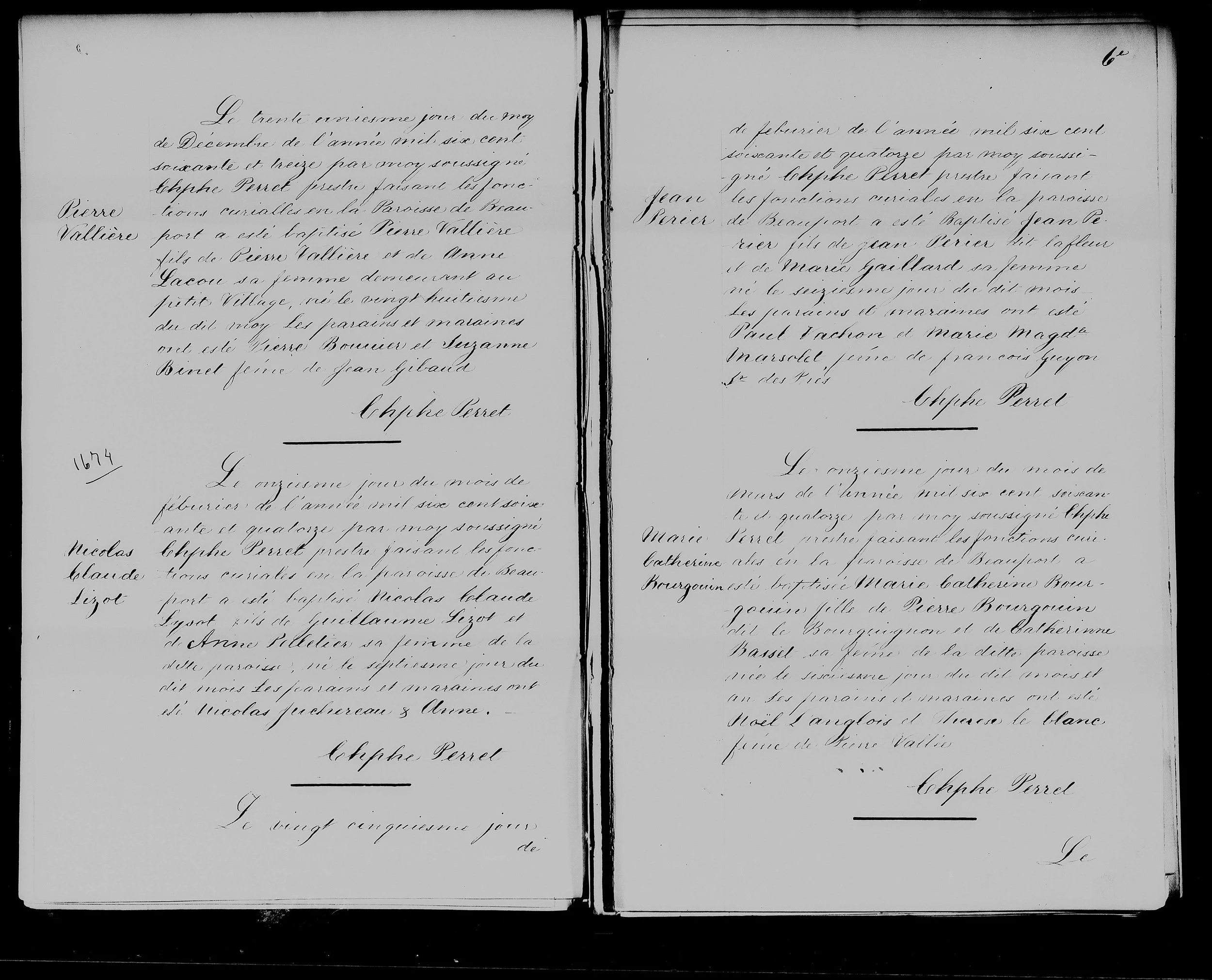

Parish Registers

- Marriage of Jean Perrier and Marie Gaillard. October 6, 1669, Quebec. (Recorded as "Jean Poirier" and "Marie Daire.")

- Baptism of Marie and Marie Marthe Perrier. August 22, 1670, Beauport. Twins.

- Baptism of Jacques Perrier. December 10, 1672, Beauport.

- Baptism of Jean Perrier (son). February 25, 1674, Beauport. "Jean Perier fils de Jean Perier dit lafleur et de Marie Gaillard."

- Baptism of François Madeleine Perrier. February 23, 1680, Beauport.

Notarial Records

- Marriage Contract of Jean Perrier and Marie Gaillard. September 22, 1669. Notary Romain Becquet, Quebec City.

- Land Concession to Jean Perrier. December 10, 1668. Seigneur Joseph Giffard, Beauport.

Genealogical Databases

- PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique). Université de Montréal. Family #1125.

- Fichier Origine. Federation of French Genealogical Societies of Quebec. Jean Perrier: Pau, Pyrénées-Atlantiques.

- Genealogy of French in North America (DGFQ/DGAQ). Denis Beauregard. Note: "DGFQ and DGAQ presume that Jean and Madeleine are the same person."

Secondary Sources

- Landry, Yves. Orphelines en France, pionnières au Canada: Les Filles du roi au XVIIe siècle. Leméac, 1992.

- Eccles, W.J. Canada Under Louis XIV, 1663-1701. McClelland and Stewart, 1964.

- Fournier, Marcel. Les officiers des troupes de la Marine au Canada, 1683-1760. Septentrion, 2017.

Continue the Story

Jean Perrier's widow, Marie Gaillard, lived for another fifty-four years after his death—remarrying, raising a blended family of eleven children, and becoming the matriarch of two converging family lines.

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Carignan-Salières — From Soldiers to Settlers

From Research to Story

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY