The Hamall Line: Thomas Eugene Hamall

Thomas Eugene Hamall

He wrote that he didn't think he could attend. But there he is in the photograph, standing next to his ex-wife at their son's wedding. This is the story of a man who lost everything—his bank, his marriage, his proximity to his only child—and spent the rest of his life trying to stay connected.

"The Missing Boy"

Thomas Eugene Hamall was born on November 23, 1904, at 201 Washburne Avenue in Chicago, Illinois. His parents were Thomas Henry Hamall, a first-generation Irish-American iron worker, and Elisabeth Emma Guilbault Gilbert, a French-Canadian immigrant whose family had recently arrived from Quebec.

Birth record index: Thomas Eugene Hamall, November 23, 1904, Chicago. Parents: Thomas Hamall and Emma Gilbert.

Three days later, on November 26, 1904, the infant was baptized at a Catholic church in Chicago. The baptismal register records him simply as "Thomas Hamall," age 10 days, with a birthdate of "Nov. 26, 1905"—a clerical error that would echo through documents for decades.

Baptismal register showing "Thomas Hamall" - November 26, 1904.

For reasons that remain unclear, his parents' marriage failed within three years. By 1907, Thomas Henry and Emma had divorced. The boy was just three years old.

In the 1910 Census, Emma appears as the wife of Alvin Hepp—but both Emma and Alvin state they have no children. Thomas Eugene, age 5, is nowhere to be found. Where was this boy during his mother's second marriage? The most likely answer: with his Guilbault grandmother and extended family.

The 1908 Thebault family photograph provides the only visual evidence from this period. In the front row, a small boy labeled "Tommy" sits among his French-Canadian cousins. His stepfather Alvin Hepp stands in the back row—the only image of Alvin that survives. By 1914, Emma and Alvin had separated, though she would continue using the name "Hepp" until 1930.

The Thebault Family, c. 1908. Young Thomas ("Tommy") sits in the front row among his Guilbault cousins. Alvin Hepp stands in the back row—the only surviving photograph of Emma's second husband.

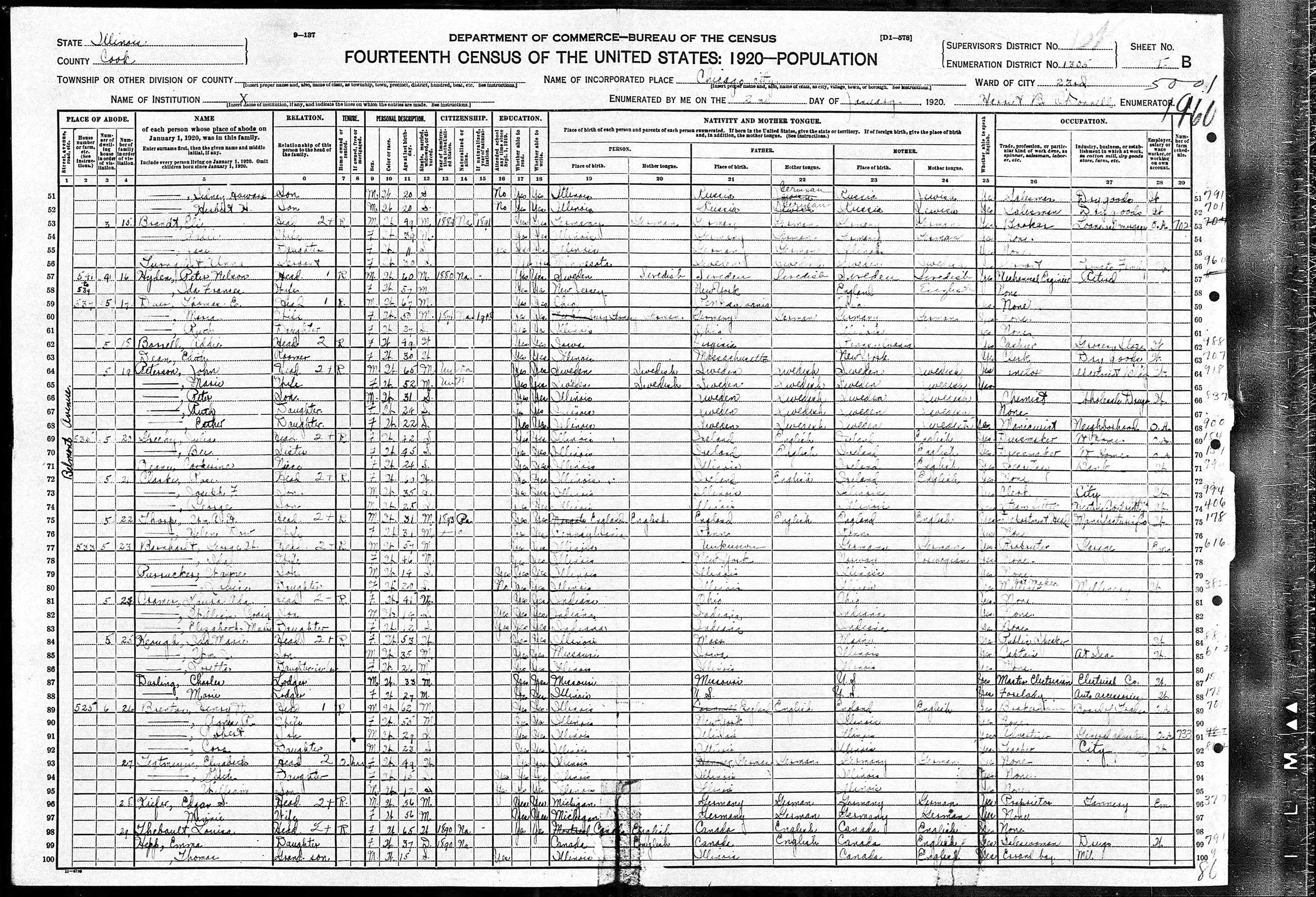

By 1920, the family situation had stabilized. The census shows fifteen-year-old Thomas living at 525 Belmont Avenue with his grandmother Marie Louise Thebault and his mother, now listed as "Emma Hepp." He was working as an errand boy—already contributing to the household economy.

1920 U.S. Census, Chicago. Thomas (age 15) appears at the bottom of the page, living with his grandmother Marie Louise Thebault and mother Emma Hepp.

"The Young Professional"

Thomas Eugene came of age during the Roaring Twenties, a time of cultural transformation in America. In Chicago, this era brought Prohibition, jazz, and significant urban development. The ambitious young man saw opportunity in the growing financial sector.

Thomas Eugene as an infant, c. 1905. This fragile photograph, torn and worn, is one of the earliest images of him.

By 1923, at just nineteen years old, Thomas had secured employment as a teller at Lake View State Bank, working at 3179 N. Clark Street while living at 525 Belmont Avenue—within walking distance of his job. This position placed him at the intersection of Chicago's financial growth and neighborhood development.

Thomas Eugene, First Communion portrait. Studio photograph from 1438-1440 Blue Island Avenue, Chicago. The serious boy in his formal suit already shows the determined expression that would carry him through decades of setbacks.

The young professional: Thomas Eugene in his twenties, dressed for success in suit, tie, and fedora.

Mother and son: Thomas Eugene with Emma, studio portrait. The bond between them would endure until the end of his life.

The 1930 Census, taken in April, shows Thomas living at 4506 N. McVickers Avenue with his mother Emma and a younger woman named "Frances"—whose relationship to the family remains a mystery. Family photographs labeled "house at McVickers" and "yard at McVickers" depict an arbor and beautiful landscaping, an early glimpse of his lifelong passion for horticulture.

1930 U.S. Census (April). Thomas Eugene living at N. McVickers with his mother Emma and the mysterious "Frances."

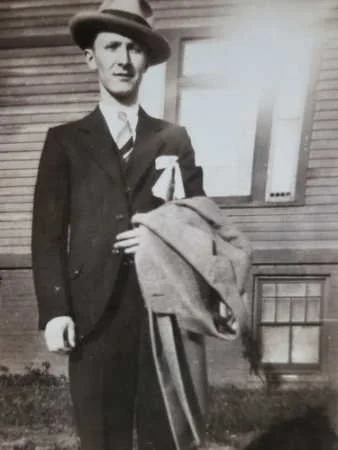

Two months later, on June 4, 1930, Thomas Eugene married his sweetheart Margaret Katherine Kenny at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church, 4640 N. Ashland Avenue in Chicago. The reception was held at the Hotel Sovereign. He was twenty-five; she was twenty-one. Their future seemed bright.

Certificate of Marriage: Thomas Eugene Hamall and Margaret K. Kenny, June 4, 1930, Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church, Chicago. Rev. K.P. Doyle officiating. Witnesses: Edward Biebel and Thelma Dick.

June 4, 1930: Thomas Eugene and Margaret Katherine Kenny on their wedding day, with best man Edward Biebel and bridesmaid Arthelma Dick.

"The Bank That Took 17 Years to Die"

Three months after the wedding, Thomas Eugene's world collapsed.

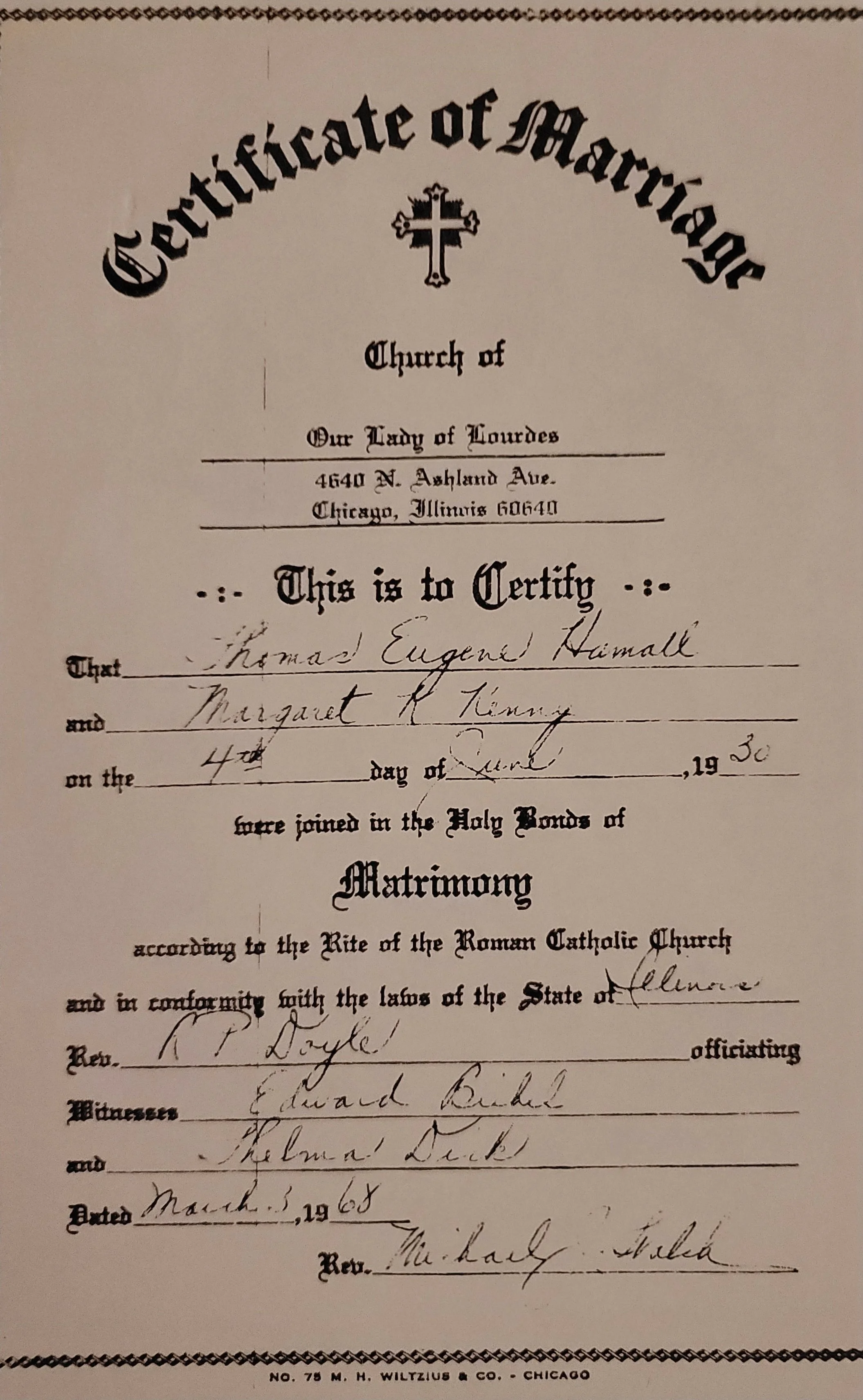

On September 22, 1930, Lake View State Bank was closed by the State Auditor. Like thousands of financial institutions across America, it could not survive the economic crisis that followed the stock market crash of October 1929. Thomas Eugene lost his job—the career he had built over seven years.

Lake View State Bank: Stock certificate (1928) and advertising measuring tape showing the building at 3179 N. Clark Street where Thomas Eugene worked.

The bank's history: Established c. 1915, Lake View State Bank constructed its notable building at 3179 N. Clark Street in 1920 at a cost of $125,000 (equivalent to $1.7 million in 2024). Thomas Eugene began working there in 1923, just three years after the building opened. The bank absorbed North Shore Exchange Bank before its own failure in 1930.

Newspaper clipping: "North Side Banks Merge" — Lake View State Bank absorbing North Shore Exchange Bank. Capital: $200,000.

But the shadow of that failure would follow Thomas Eugene for nearly two decades. The bank's liquidation dragged on through the Depression, through World War II, and into the postwar era.

March 1947: Legal notice announcing the FINAL dividend for Lake View State Bank claimants. Seventeen years after the bank's failure, the liquidation was finally complete. Total recovery: approximately 47.5 cents on the dollar, paid out in six dividends over seventeen years.

The bank failed three months after his wedding. The final claims notice was published seventeen years later. The institution that launched his career haunted him for half his adult life.

After the bank's collapse, Thomas found work with Bowman Dairy Company as a milkman—a humbling transition from bank teller to delivery driver, but honest work during desperate times.

"The Only Census"

On July 21, 1932, Thomas Eugene and Margaret welcomed their only child: Thomas Kenny Hamall, born in Evanston, Illinois. The couple was living at 4869 N. Ashland Avenue, with Margaret's parents.

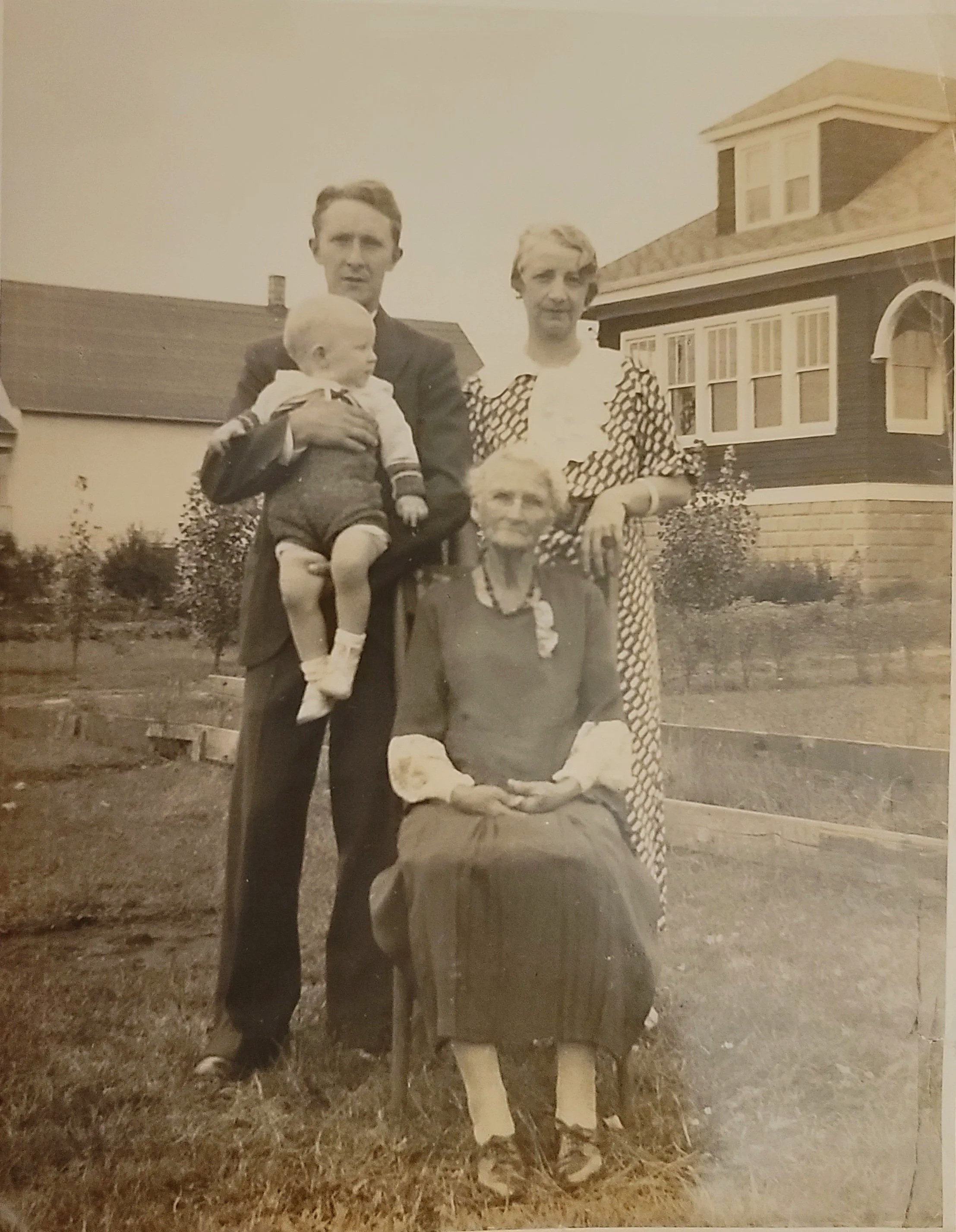

Four Generations, c. 1932-1933: Baby Thomas Kenny Hamall held by his father Thomas Eugene. Behind them stand Emma (Guilbault) Gilbert Hamall and her mother Marie Louise Thebault. Four generations of this family, captured in a single frame.

By 1940, the family had moved to 33 N. Menard Avenue in Chicago. The census that year captures what no other federal document ever would: Thomas Eugene Hamall as the head of an intact household, with his wife Margaret and their seven-year-old son Thomas Jr.

1940 U.S. Census, Chicago Ward 37: The only federal census showing Thomas Eugene, Margaret, and young Thomas Kenny living together as a family.

This single document—the 1940 Census—is the only federal record that proves this family unit ever existed. By 1942, divorce would scatter them. The 1950 Census would find them living in separate households in Miami. This one page is all we have.

Thomas Eugene's World War II draft registration card, completed in 1940, reveals telling details. His address is listed as 291 Lionel Road, Riverside—but the original entry, 4869 N. Ashland Avenue (Margaret's parents' home), has been crossed out. His employer: Bowman Dairy Company, Harlem & Lake, River Forest, Illinois. The physical description: 5'8", 145 pounds, blue eyes, brown hair.

WWII Draft Registration Card: Thomas Eugene Hamall. Note the crossed-out address (4869 N. Ashland, Margaret's parents) replaced with 291 Lionel Rd, Riverside. Wife listed as "Mrs. Margaret Catherine Hamall."

The 291 Lionel Road address was a cottage in Riverside, Illinois—a suburban retreat. A photograph from this period shows him relaxed in the yard with a dog, the kind of peaceful domestic scene that would soon disappear from his life.

Thomas Eugene at the cottage, 291 Lionel Road, Riverside, Illinois. A rare moment of domestic peace before the family fractured.

Sometime around 1941-1942, Thomas Eugene and Margaret divorced. The exact reasons are lost to time. Margaret, taking their son Thomas Kenny, relocated to Miami, Florida to live with or near her parents, Thomas P. and Ellen Kenny. Thomas Eugene remained in Chicago—1,200 miles away from his only child.

"1,200 Miles"

The distance was vast. Margaret and young Tom were building a new life in Miami. Thomas Eugene was alone in Chicago, working for the dairy, watching his son grow up through letters and occasional visits.

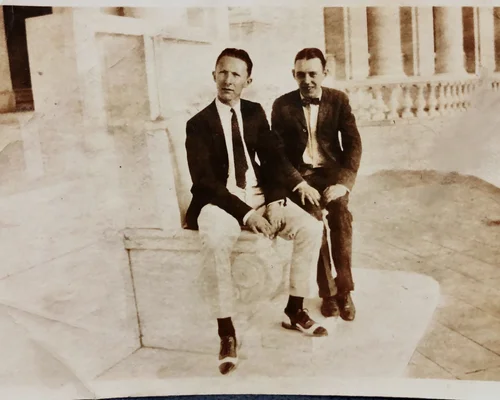

In Easter 1947, Thomas Eugene made a journey that his son would later call "pivotal." He traveled from Chicago to Washington, D.C., accompanied by his first cousin Emmett John Holland—son of his aunt Mary Hamall Holland. The purpose: to visit fifteen-year-old Thomas Kenny, then enrolled at St. Charles Seminary in Catonsville, Maryland.

Washington, D.C., 1947: Thomas Eugene Hamall (left) with his first cousin Emmett John Holland. The two traveled together from Chicago to visit Thomas Kenny at seminary during Easter vacation.

The 1947 Washington trip is documented in detail in They Were Never Photographed Together. Forensic analysis of photographs taken at the U.S. Capitol confirmed that Thomas Eugene and his son were there at the same time—though they were photographed separately. Tom's handwritten notes about this period read simply: "1947 spent Easter vacation in DC."

Whatever was said between father and son during that visit changed the trajectory of Tom's life. Shortly after, he left seminary and returned to Miami.

By 1950, Thomas Eugene had made a decision. If he couldn't bring his son back to Chicago, he would go to Miami himself.

The 1950 Census shows Thomas Eugene living at 289 Rear NE 90th Street in Miami with his mother Emma. His occupation: lawn maintenance. At forty-five years old, he was starting over—reinventing himself in a tropical climate far from the Chicago bank where he had once imagined building a career.

The 1953 Miami City Directory tells a remarkable story in three brief entries:

Hamall Emma wid Thomas — [widow notation]

Hamall Thomas E landscaper — 3291 NW 103rd

Hamall Thomas K asst mngr State Loan Corp — 1430 NE 140th

For the first time since the divorce, father and son were living in the same city. Thomas Eugene was fifty-three, a landscaper. Thomas Kenny was twenty-one, an assistant manager at a loan company. Emma, now a widow, was nearby.

"Bow and Arrow Gardens"

In Miami, Thomas Eugene finally found his calling. The passion for horticulture glimpsed in the McVickers yard photographs and the Riverside cottage garden flourished in Florida's tropical climate. He established Bow and Arrow Gardens—later Bow-Arrow Nursery—specializing in nutritional, insect, and fungus spray treatments for trees and shrubs.

Newspaper advertisement: BOW-ARROW GARDENS, Tom Hamall, Owner. "Nutritional, Insect and Fungus Spray of Trees and Shrubs."

Thomas Eugene in his element: palm trees, water, tropical paradise. Miami became his home.

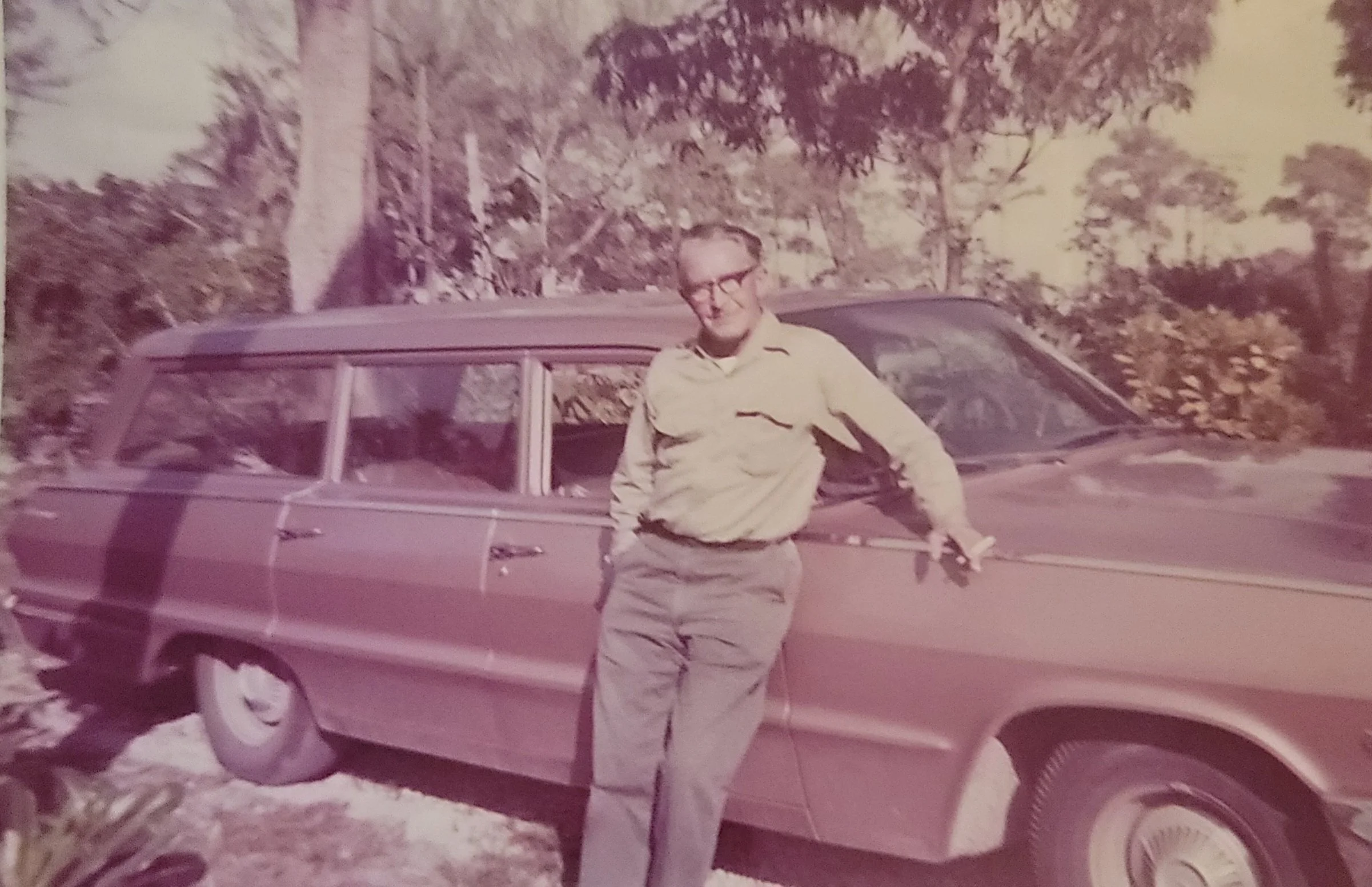

1963: Thomas Eugene with his station wagon—the working vehicle of a successful nurseryman.

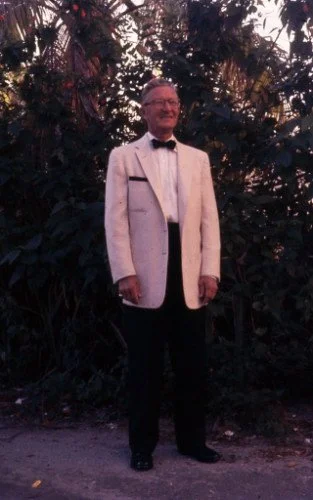

By the 1960s, Thomas Eugene had become a respected figure in Miami's horticultural community. He served as an officer of the Horticultural Spraymen's Association and was elected president of the Dade County chapter.

"Dade Spraymen Choose Hamall": Newspaper clipping announcing Thomas E. Hamall's election as president of the Dade County chapter of the Horticultural Spraymen's Association of Florida.

1961: Thomas Eugene at a Horticultural Spraymen's Association banquet, elegant in a white dinner jacket amid the tropical foliage he loved.

In 1963, Thomas Eugene was quoted in the Miami Herald regarding proposed legislation to regulate the sale and use of toxic insecticides. As president of the association, he supported the bill—advocating for public safety in the use of dangerous chemicals.

"Insecticide Control Bill Is Withdrawn": Miami Herald, May 16, 1963. Thomas E. Hamall, president of the Dade chapter of the Horticultural Spraymen's Association, is quoted supporting regulation of toxic chemicals.

He spent his final years advocating for the regulation of the chemicals he worked with daily. Four years later, he was dead of lung cancer—likely caused by exposure to those same chemicals, combined with a lifetime of smoking.

The bitter irony was not lost on his family."Dear Daughter to Be"

In the fall of 1957, Thomas Kenny Hamall—now twenty-five years old and working for the American Cancer Society in New York—became engaged to Barbara O'Brien of Caldwell, New Jersey. The wedding was set for November 28, 1957, at St. Aloysius Church in Caldwell.

On November 12, 1957, Thomas Eugene sat down at his home at 529 N.M. 143rd Street in Miami and wrote a letter to the woman his son was about to marry.

The wedding card Thomas Eugene sent to his future daughter-in-law: "Best Wishes for the Bride and Groom."

Miami, Florida

November 12, 1957

I want to thank you for the invitation to your wedding and reception. I hope my son will give you all the love, happiness and all other things of this world that are so essential for a happy marriage.

Dear daughter - at the present time I do not think I will be able to attend your reception. Will arrive in New York - Thursday - November 21 at 5:25 A.M.

I am looking forward to seeing you soon.

Dad

Hamall

The letter in Thomas Eugene's own hand: "My Dear Daughter - to be..."

He wrote that he didn't think he could attend the reception. But look at the photograph:

November 28, 1957: Thomas Eugene Hamall stands next to his son and new daughter-in-law at their wedding reception. To his left: the priest. To the far right: Margaret—his ex-wife, fifteen years after their divorce. They came together for their son.

He wrote that he didn't think he could make it to the reception. But there he is—standing in his light suit, a boutonnière on his lapel, next to the son he had followed 1,200 miles to stay close to. And there, at the edge of the frame, stands Margaret: the woman he had married twenty-seven years earlier, divorced fifteen years before. They came together, these two people whose marriage had ended, to celebrate the beginning of their son's.

"The Legacy"

Thomas Eugene Hamall died on July 6, 1967, in Miami-Dade County, Florida. He was sixty-two years old. The cause: lung cancer—the cruel intersection of the chemicals he worked with and a lifetime of smoking.

His son Thomas Kenny traveled from New Jersey to Miami to make the funeral arrangements. Thomas Eugene was buried in North Miami Cemetery, in the tropical landscape he had come to love.

After the funeral, Thomas Kenny had another task: his grandmother Emma, now in her eighties and residing in a Miami nursing home, needed care closer to family. He moved her to Villa Maria nursing home in Plainfield, New Jersey, where she would spend her final years near her grandson, his wife Barbara, and their growing family of daughters.

But Thomas Eugene left something behind—something that would bridge the distance one final time.

The pocket watch: Engraved with the initials T.E.H.—Thomas Eugene Hamall. Beside it, the photograph of Thomas Eugene in his white dinner jacket, the successful nurseryman who rebuilt his life in Miami. Thomas Kenny Hamall wore this watch to every one of his daughters' weddings.

The pocket watch with the initials T.E.H. Thomas Kenny wore it to every daughter's wedding—six times in all. Each time he fastened that chain, he carried his father with him to witness the family moments Thomas Eugene had worked so hard not to miss.

Thomas Eugene Hamall's life was shaped by loss: the loss of his parents' marriage at age three, the loss of his banking career in the Depression, the loss of his own marriage and daily presence in his son's life. But the documentary record tells a different story than the one "absent father" might suggest.

He traveled from Chicago to Washington to visit his teenage son at seminary. He moved 1,200 miles to be in the same city. He wrote to his son's fiancée calling her "my dear daughter to be." He arrived in New York at 5:25 AM on a November Thursday, uncertain whether he could attend the reception—and then he was there, standing next to the son he had never stopped trying to reach.

From bank teller to milkman to nurseryman. From Chicago to Miami. From divorce to reconciliation at a wedding reception. This was the life of Thomas Eugene Hamall—the father who tried.

Document Gallery

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY