The Hamall Line: Thomas Henry Hamall

Thomas Henry Hamall

"A man of quiet resilience who built something permanent amid tragedy, separation, and hardship—a laborer who never wavered in his care for his mother, his son, or his home."

Thomas Henry Hamall was born on May 7, 1880, in Chicago, Illinois—a city alive with the momentum of industry and immigration. He was the eldest surviving child of Irish immigrants Owen Hamall and Catherine Mary Griffith, baptized on May 16 at Holy Name Cathedral on State Street. His sponsors were his aunt and uncle, John and Mary Griffith—Kate's siblings who lived with the family at 50 Bremer Street.

The world into which Thomas arrived was one of possibility, forged through hard work and close family ties. His father Owen worked as an iron molder, a skilled trade essential to Chicago's industrial expansion in the decades following the Great Fire of 1871. But the decade of the 1890s would shatter the family Thomas knew.

"HAMALL—Thomas Hamall, fond brother of Mrs. Mary Holland. Funeral Monday, Jan. 31, 9 a.m., from chapel, 3004 Ogden avenue, to Blessed Sacrament church. Interment Calvary."

A Childhood of Loss

Thomas was thirteen years old in 1893 when tragedy struck with devastating force. That year, he lost four siblings in rapid succession: William, Lizzie, Katie, and Eugene—all victims of the childhood diseases that ravaged immigrant neighborhoods. The family plot at Calvary Cemetery, purchased by his grandmother Elizabeth Griffith in 1870, received four small bodies that year.

Five years later, in 1898, Thomas lost his father. Owen Hamall died of meningitis at age 51, leaving his widow Kate with two surviving children: eighteen-year-old Thomas and thirteen-year-old Mary. The 1897 Chicago Tribune had listed Owen on the "Destitute List"—a public record of families in desperate need. By the time Owen died, blindness from his illness had already ended his working life.

At eighteen, Thomas became the man of the household. The Chicago city directories tell the story of his trajectory: in 1898, listed as a laborer at 94 Sholto Street. By 1902, an iron worker boarding at 201 Washburne Avenue—the same address where his widowed mother Kate worked as a dressmaker. By 1905, still at Washburne, still an iron worker, still alongside his mother.

Marriage, Fatherhood, and Divorce

On January 31, 1904, at the age of twenty-three, Thomas married Elisabeth Emma Guilbault—known as Emma Gilbert—a French Canadian woman whose heritage enriched the family's cultural roots. Their wedding was held at Notre Dame of Chicago Roman Catholic Church, a landmark that had served Chicago's immigrant Catholic population since 1864.

Later that year, on November 26, 1904, they welcomed a son: Thomas Eugene Hamall. The boy would carry forward not only his father's name but his grandfather Owen's middle name—Eugene—the same name given to the youngest of the four children lost in 1893.

The marriage did not last. By October 18, 1907, Emma had obtained a divorce, with a decree requiring Thomas to pay four dollars weekly for his son's support. Despite the divorce, Thomas remained present in his son's early life and maintained close ties with his family. The 1910 census shows him living with his mother Kate and his sister Mary Holland's family at 2639 South Ridgeway Avenue—listed as "brother-in-law" in John Holland's household.

The Cottage at 291 Lionel Road

In 1911, Thomas set out to create something permanent. Using $300 of his own savings, a $400 loan from his mother Kate, and $250 borrowed from others, he purchased land at 291 Lionel Road in Riverside, Illinois—a planned community designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the architect of New York's Central Park.

On that lot, Thomas built a modest cottage: twenty-four feet by twenty-four feet, a one-room structure that represented everything he had worked for. By August 1911, the cottage was complete. Thomas and his widowed mother moved in together, and it would remain his only home for the rest of his life.

Riverside was no ordinary suburb. Olmsted's 1869 design created curving streets, preserved natural landscapes, and established the village as America's first planned suburban community. For Thomas—the son of an immigrant iron molder who had grown up amid Chicago's dense tenements—Riverside represented a different kind of life.

His mother Kate lived with him there until her death on November 12, 1919, at Chicago State Hospital, where tuberculosis claimed her after twenty-one years as a widow. Thomas buried her in the family plot at Calvary Cemetery—Lot 17, Block 14, Section D—the same ground that held his grandmother Elizabeth Griffith, his uncle John Griffith, his siblings, and his father.

Hamall v. Petru: A Fight for Home

The cottage Thomas built would become the subject of a legal battle that reached the Illinois Supreme Court. In 1914, Thomas persuaded his ex-wife Emma—now Mrs. Hepp—to release her claims for back child support. He paid her $25 and agreed to deed the property to Frank J. Petru in trust for their son Thomas Eugene, subject to Thomas Henry's life estate.

But in November 1924, Emma filed a petition in divorce court claiming Thomas had willfully neglected to pay the $4 weekly support ordered in their 1907 decree. She argued he owed $2,500 in back payments and sought to seize the Riverside property. The case wound through the courts for four years.

On October 25, 1928, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in Thomas's favor. The court found that the property qualified as his homestead under Illinois law and was therefore protected from seizure for debt. The ruling in Hamall v. Petru (331 Ill. 465) established precedent still cited in Illinois property law today—twelve cases between 1930 and 2020 have referenced this decision.

It was a personal victory that reinforced the meaning of home. The cottage Thomas had built with loans from his mother—the widow who had lost her husband, four children, and her own mother—could not be taken from him.

A Second Chapter

The 1920 census captures Thomas in transition: a divorced millwright, age 39, boarding at 1031 Robey Street (now Damen Avenue) in Chicago. His mother had just died the previous year. But Thomas would not remain alone.

On October 11, 1922, Thomas married Margaret Schoenman Auslander at the City of Berwyn, Cook County. He was 42; she was 40, originally from Hungary. A police magistrate named Jos. Cerny performed the ceremony. The marriage certificate shows Thomas's residence as Riverside—he had returned to his cottage.

Two family photographs from that day survive—both taken at an Olmsted-designed bridge in Riverside. In one, Thomas stands confidently, hat in hand, a slight smile beneath his mustache. In another, his son Thomas Eugene, now eighteen, poses at the same location. Father and son, photographed separately at the same event, documenting a new beginning.

The 1930 census shows Thomas and Margaret at 291 Lionel Road. He was working as a millwright at a bottleworks; the house was valued at $5,000—a substantial appreciation from his $300 purchase nineteen years earlier. Margaret died in 1936, leaving Thomas a widower for his final years.

A Working Life

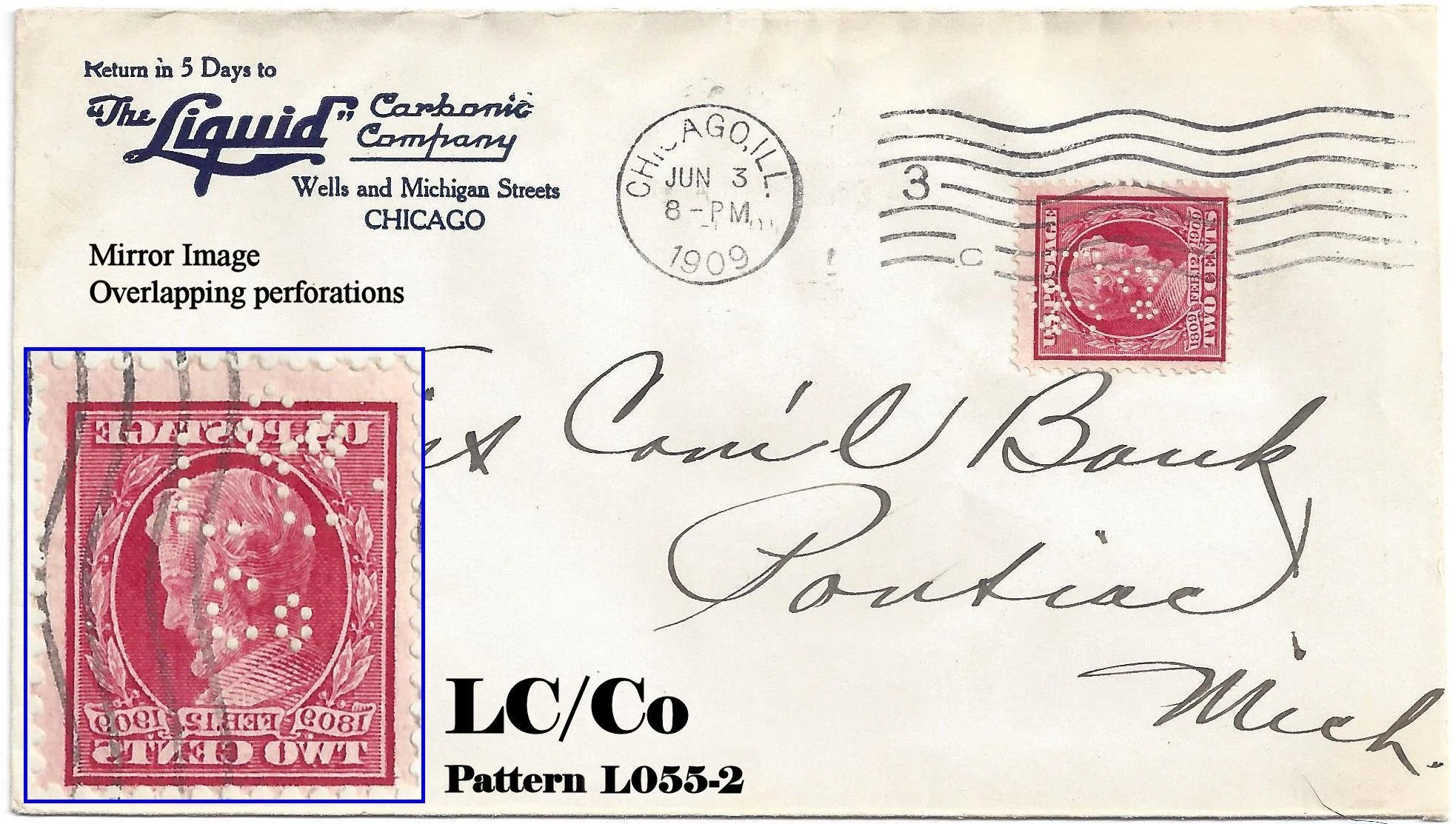

Thomas Henry's occupations traced the arc of Chicago's industrial economy. City directories and census records document his progression: laborer at 18, iron worker by 22, architect (or draftsman) by 20, millwright by his thirties. His 1918 World War I draft registration card shows him working as an "oiler" at the Liquid Carbonic Company—a major Chicago manufacturer of carbonation equipment at Wells and Michigan Streets.

By the 1930s, he had moved to the bottleworks. His death certificate in 1938 lists his final occupation as "watchman" at a building—five years in that role. Like his father Owen, who had worked as an iron molder until blindness forced him to stop, Thomas spent his life in skilled manual labor, adapting as circumstances demanded.

Final Rest

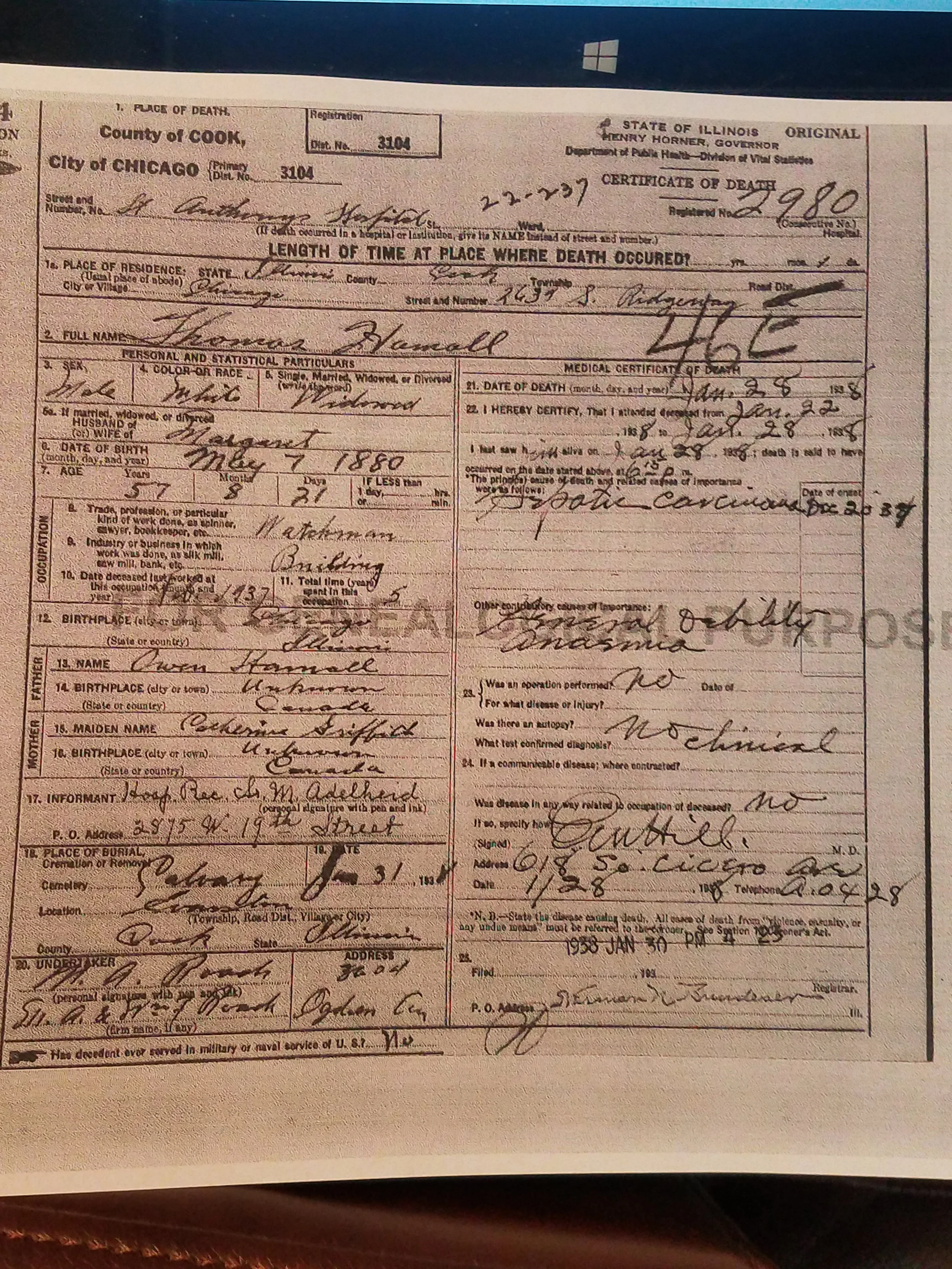

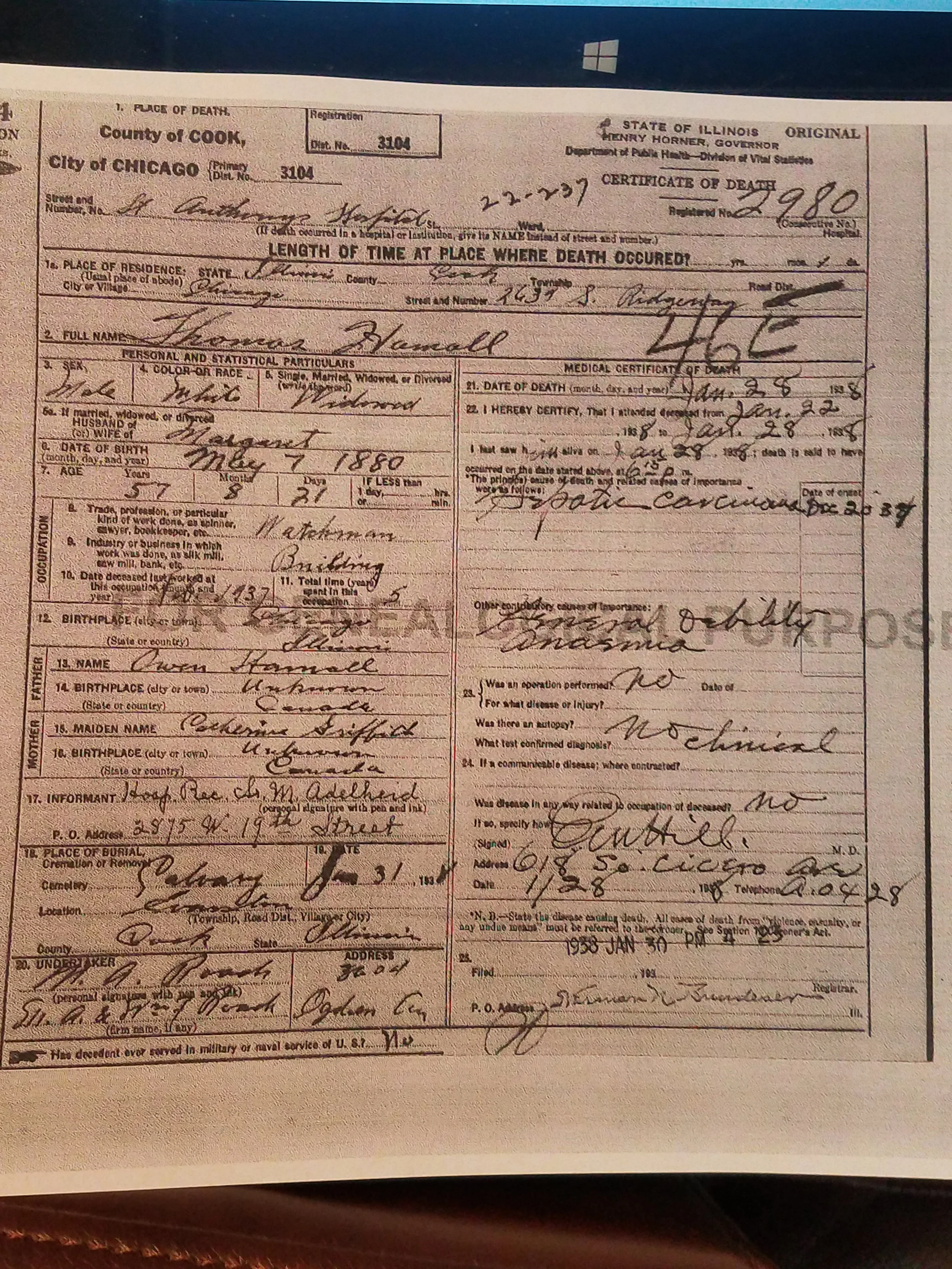

Thomas Henry Hamall died on January 28, 1938, at St. Anthony's Hospital in Chicago. He was 57 years old—the same age his father Owen had been when illness began its final assault. The cause of death was gastric carcinoma, with general debility and anemia as contributing factors. He had been attended by a physician since January 22.

His death certificate names his parents: Owen Hamall, birthplace Canada; Catherine Griffith, birthplace unknown, Canada. Even in death, the family's Canadian chapter—the Montreal years between Ireland and Chicago—appeared in the official record.

Thomas was buried on January 31, 1938—three days after his death—at Calvary Cemetery in Evanston. The funeral Mass was held at Blessed Sacrament Church, with services from the chapel at 3004 Ogden Avenue. His obituary named only one survivor: "fond brother of Mrs. Mary Holland."

He was laid to rest in Lot 17, Block 14, Section D—the family plot his grandmother Elizabeth Griffith had purchased in 1870. The cemetery records show the interments in that ground: Elizabeth Griffith herself, her son John (who died in 1926), Catherine Hamall (Thomas's mother, 1919), and now Thomas. The plot also held Owen and the four children lost in the 1890s, though their individual markers have been lost to time.

The family plot comes full circle. Thomas Henry was buried in the same ground purchased by his maternal grandmother sixty-eight years earlier—returning the sole surviving son to lie with the family he lost in childhood.

A Legacy of Persistence

Thomas Henry Hamall wasn't a man of headlines, but of steady purpose. He survived the loss of four siblings, his father's death, a failed marriage, and a four-year legal battle—and through it all, he never abandoned his responsibilities to his mother, his son, or his home.

The cottage at 291 Lionel Road outlived him. When Thomas died, his son Thomas Eugene inherited the property—the same property Thomas Henry had fought to protect all the way to the Illinois Supreme Court. The 1940 WWII draft registration for Thomas Eugene shows a telling detail: his original address (4869 N. Ashland Avenue, Chicago) was crossed out and replaced with 291 Lionel Road, Riverside.

Father and son had lived separately for decades. But when Thomas Eugene's own marriage faltered, he returned to the cottage his father had built. The property that represented everything Thomas Henry had worked for became a refuge for the next generation.

Thomas Kenny Hamall—Thomas Eugene's son, Thomas Henry's grandson—held Riverside close to his heart. According to family memory, he cherished visits to the Riverside library and insisted on revisiting the town during later family trips to Chicago. The cottage his great-grandfather built in 1911 had created bonds that lasted generations.

Timeline

Document Gallery

Primary sources documenting Thomas Henry Hamall's life, organized by record type. Click any document for full details.

Baptism Record, 1880

Holy Name Cathedral, Chicago. Parents: Owen Hamill & Cath. Griffith. Sponsors: John & Mary Griffith.

Death Certificate, 1938

St. Anthony's Hospital, Chicago. Cause: gastric carcinoma. Parents: Owen Hamall, Catherine Griffith.

Cemetery Interment Card, 1938

Calvary Cemetery, Evanston. Lot 17, Block 14, Section D. Interment January 31, 1938.

Marriage License, 1904

Thomas H. Hamall (24) to Emma Gilbert (21), January 31, 1904, Cook County, Illinois.

Marriage Certificate, 1922

Thomas H. Hamall (42, Riverside) to Margaret Auslander (40, Berwyn), October 11, 1922.

1880 U.S. Census

50 Bremer Street, Chicago. Thomas (1 month) with parents Owen & Kate, "Thornton" listed as brother.

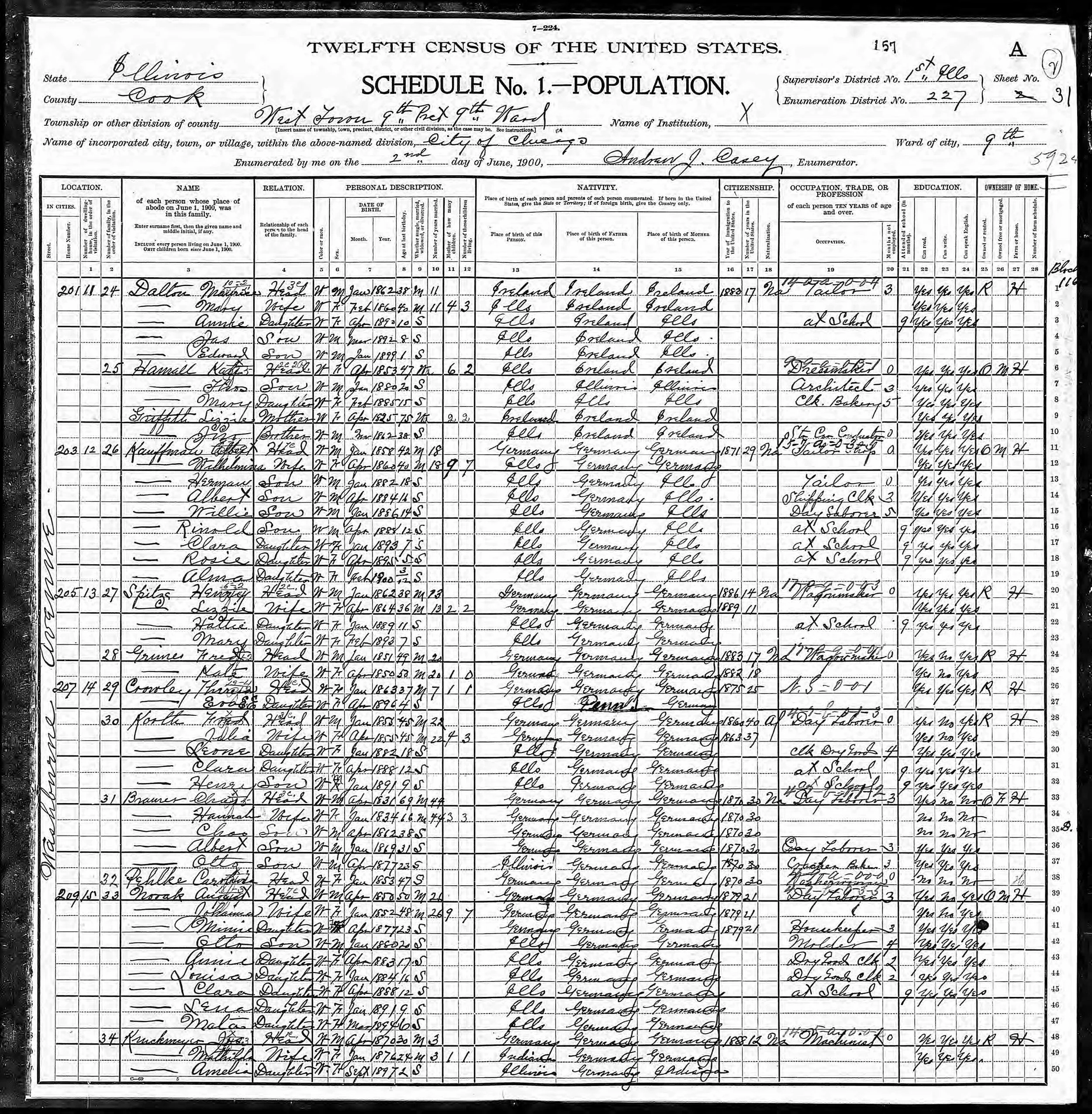

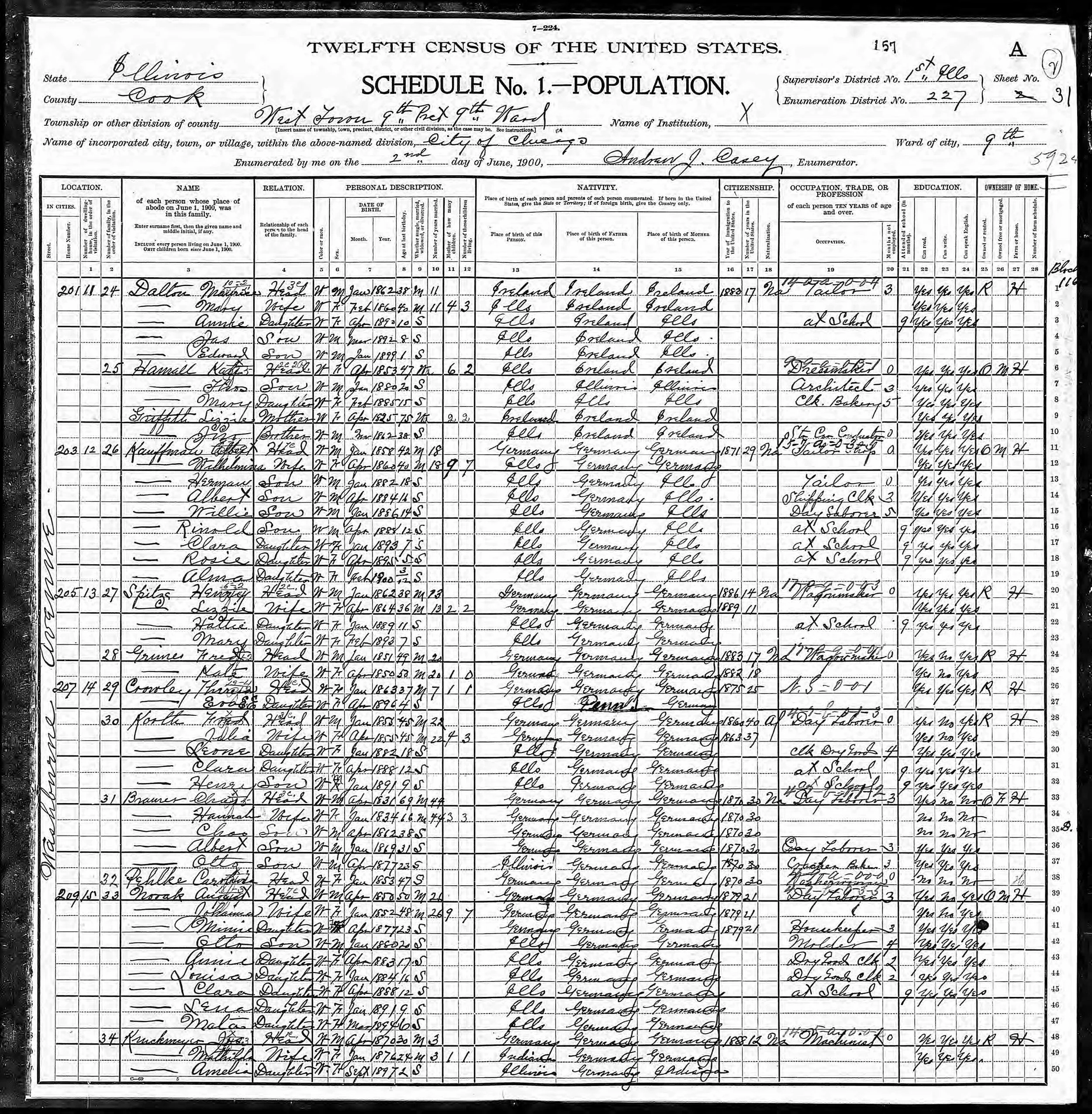

1900 U.S. Census

201 Washburne Ave, Chicago. Thomas (20, architect) with widow Kate, sister Mary, grandmother Elizabeth.

1910 U.S. Census

2639 S. Ridgeway Ave, Chicago. Thomas (28) with Holland family and mother Kate.

1920 U.S. Census

1031 Robey Street, Chicago. Thomas (39, divorced, millwright) as boarder.

1930 U.S. Census

291 Lionel Road, Riverside. Thomas (49, millwright) and Margaret, home valued at $5,000.

WWI Draft Registration, 1918

Thomas Henry Hamall, 38, oiler at Liquid Carbonic Co. Residence: 291 Lionel Road, Riverside.

Hamall v. Petru, 1928

Illinois Supreme Court decision protecting Thomas Henry's homestead from seizure for debt.

Thomas Henry Hamall, 1922

Only known photograph, taken at his wedding to Margaret Auslander in Riverside.

Thomas Eugene Hamall, 1922

Son of Thomas Henry, photographed same day at Olmsted bridge in Riverside.

The Cottage at 291 Lionel Road

The home Thomas Henry built in 1911 and protected through the Illinois Supreme Court.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY