Hero in the Depths: Cherry Mine Disaster

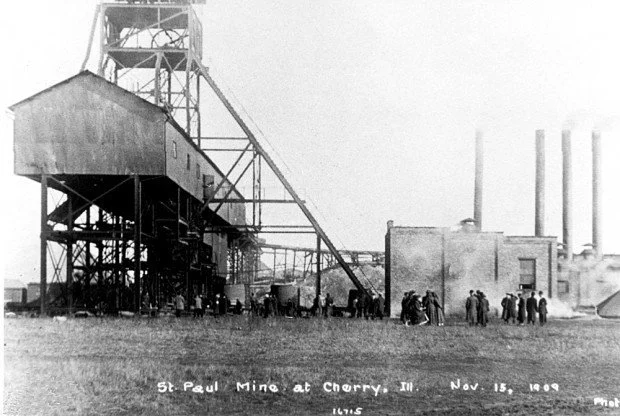

St Paul Mine at Cherry Hill - Site of the 1909 Cherry Mine disaster that killed 259 miners

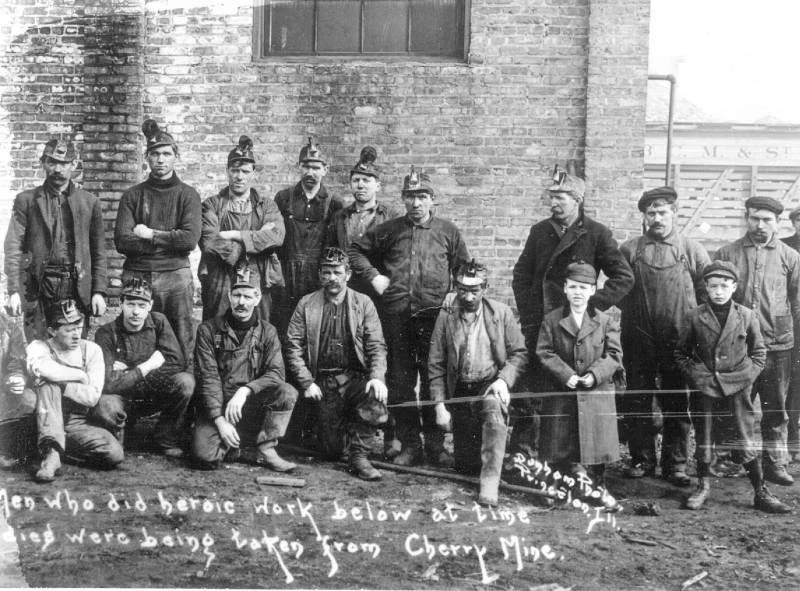

How a Chicago Fire Captain's expertise helped enable the most miraculous mine rescue in American history

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: Uncovering the extraordinary stories hidden in ordinary family histories, one ancestor at a time.

On the morning of November 13, 1909, the mining town of Cherry, Illinois, seemed like any other prosperous industrial community. Built around the St. Paul Coal Company's mine, Cherry housed 2,500 residents—mostly immigrant families drawn by steady work and company-built homes. By sunset that day, 259 men would be dead, and the town's name would be seared into American industrial history.

What followed was not just a rescue operation, but a convergence of industrial expertise, heroic sacrifice, and what many called divine intervention. At the center of this story stands Captain Thomas P. Kenny of the Chicago Fire Department—my great-grandfather—whose technical knowledge and leadership helped make possible one of the most remarkable mine rescues ever recorded.

"The Mine is on Fire!"

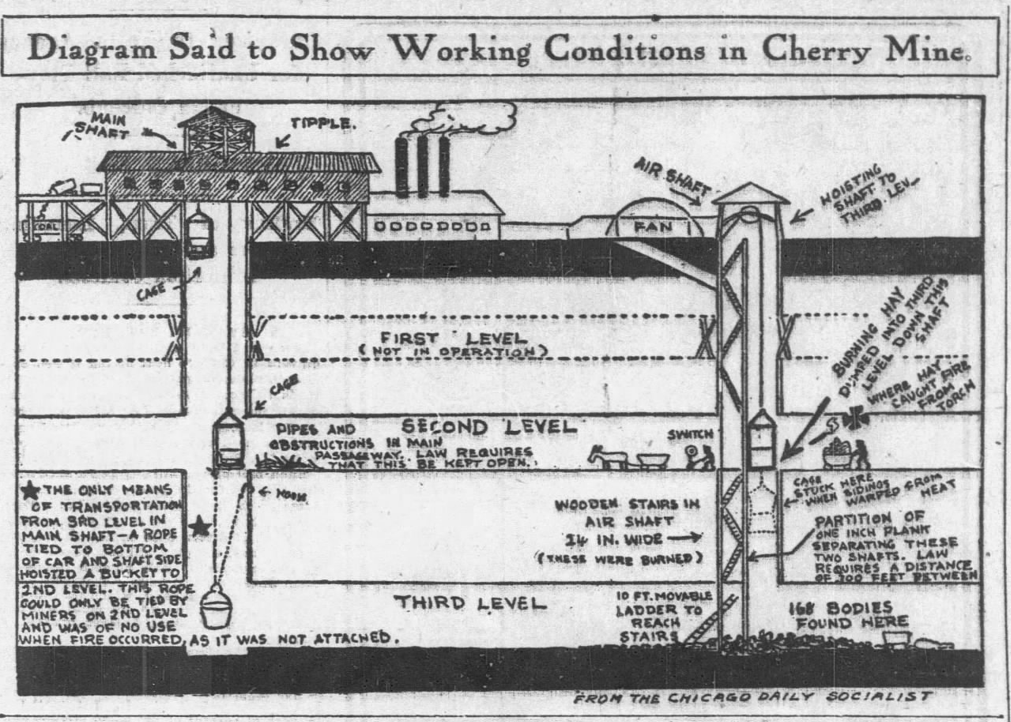

At 1:30 PM on November 13th, a simple accident triggered an unimaginable catastrophe. A cart of hay, being lowered to feed the mine's mules, caught fire near the air shaft. Fed by the mine's ventilation system, the flames spread rapidly through the timber supports of the second vein, 315 feet underground.

Of the 484 men working in the mine that day, many never had a chance. The fire spread with terrifying speed, filling galleries with deadly smoke and poisonous gases. Those who could reach the main shaft fought desperately to escape, but the flames soon made even that route impassable.

In an act of extraordinary heroism, twelve men—including mine bosses John Bundy and Alex Norberg—repeatedly descended into the inferno to rescue their trapped comrades. They saved dozens of lives before the flames overwhelmed them. All twelve perished in their final rescue attempt, their bodies brought to the surface still burning.

The Herald News of Joliet reported from eyewitnesses Thomas Lantry and Eddie Carpenter, who described scenes of unimaginable horror: "The children were clinging to their skirts and nothing would pacify them... The women were crying, moaning and wringing their hands."

Smoke Rising from the Cherry Mine

Smoke rising from the Cherry Mine on November 13, 1909 - the day of the disaster.

Chicago Responds

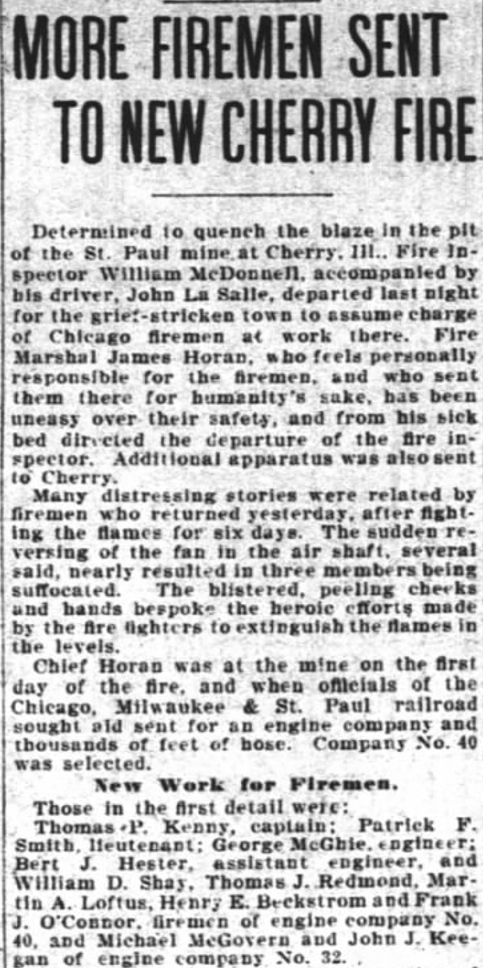

News of the disaster reached Chicago Fire Marshal James Horan at 2:20 PM on November 16th. Within ten minutes, Captain Thomas P. Kenny of Engine Company 40 had assembled his crew and was racing toward Cherry on what would become one of the most dangerous missions of his 44-year career.

Captain Thomas P. Kenny

Captain Thomas P. Kenny, Chicago Fire Department, Engine Company 40, who led the specialized firefighting response to the Cherry Mine disaster.

Contemporary newspaper coverage and photographs document the massive emergency response that brought Captain Kenny and his Chicago firefighters to Cherry, Illinois. The scale of the disaster required expertise from across the region.

Racing Against Time

Kenny's response exemplified the Chicago Fire Department's legendary efficiency. "At 2:30, ten minutes later, just as if we had been called to fight a fire in the loop district of the city, we were at the depot and had boarded the train," he recalled. "We took with us one engine and a truck. The men carried with them all their implements and their hard fire fighting clothes."

The special train configuration revealed the scale of the deployment: "The train consisted of two freight cars in front, one baggage car and one flat car, on which the engine and the truck were loaded." This wasn't just a rescue mission—it was a full industrial firefighting operation transported by rail.

"I never in my life traveled so fast," Kenny wrote of the journey. "We went over the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy railroad to Mendota. The distance is eighty-three miles, and we made it in sixty-two minutes, more than a mile a minute."

This rapid response time was crucial. Every minute counted as fires spread through the mine's timber supports and deadly gases accumulated in unventilated areas. The railroad's willingness to clear tracks and run at dangerous speeds demonstrated how quickly word of the disaster's severity had spread beyond Cherry to major transportation networks.

Fighting Fire in Hell

What Kenny found was a technical nightmare. The mine wasn't just on fire—it was a complex system of shafts, galleries, and ventilation that required specialized knowledge to navigate safely. The mine officials initially refused to let his men descend, fearing the conditions were too dangerous.

"The next morning we conveyed the engine to the pond nearby and laid out a lead of hose to the main shaft," Kenny recorded. "I went to the mine officials and asked permission to set my men to work and go down into the shaft and begin at once the fighting of the fire, but they referred me to the mine experts and examiners, and they told me that it was folly to attempt to enter that mine."

Kenny's frustration was palpable. His men were ready—they lived with danger daily. But mine fires presented unique hazards: not just flames and heat, but deadly gases like "black damp" (carbon monoxide) and "white damp" (carbon monoxide mixed with other gases) that could kill silently and instantly.

When finally permitted to descend on Thursday evening, November 18th, Kenny led his men into what he described as an "inferno of flames." Working in relays due to the extreme conditions, they fought fires that had spread across the entire main bottom of the mine.

"The heat was unbearable," Kenny wrote. "It burned their faces and even pierced through their rough mine clothing and scorched the skin underneath."

The Technical Challenge

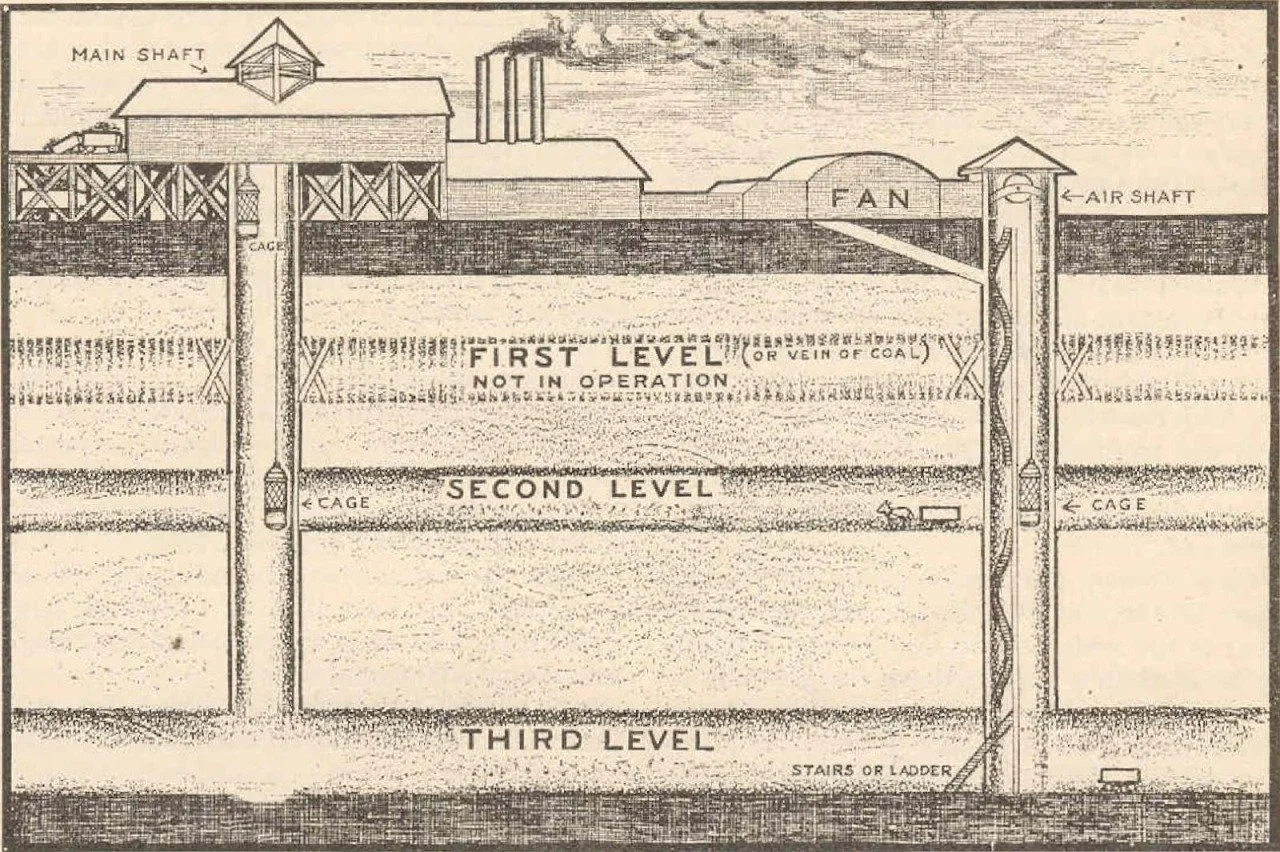

Kenny's account reveals the sophisticated understanding required for mine fire suppression. Unlike building fires, mine blazes create their own weather systems, drawing air through complex ventilation networks and creating backdrafts that could trap rescue workers.

"I firmly believe that if we could have reached the east side of the second vein we could have completely conquered the fire," Kenny noted. "This was impossible, as it was buried in vast tonnage of debris and cave-ins."

His strategic thinking was crucial: understanding that water alone couldn't reach fires buried under collapsed timbers, that ventilation fans had to run continuously to prevent deadly gas accumulation, and that different sections of the mine required different approaches.

The Chicago Tribune reported on December 3rd that mine experts praised the Chicago Fire Department's work, noting their ability to adapt urban firefighting techniques to the unique challenges of underground blazes.

Cross-section diagram of the Cherry Mine showing the complex three-level system Captain Kenny's men had to navigate.

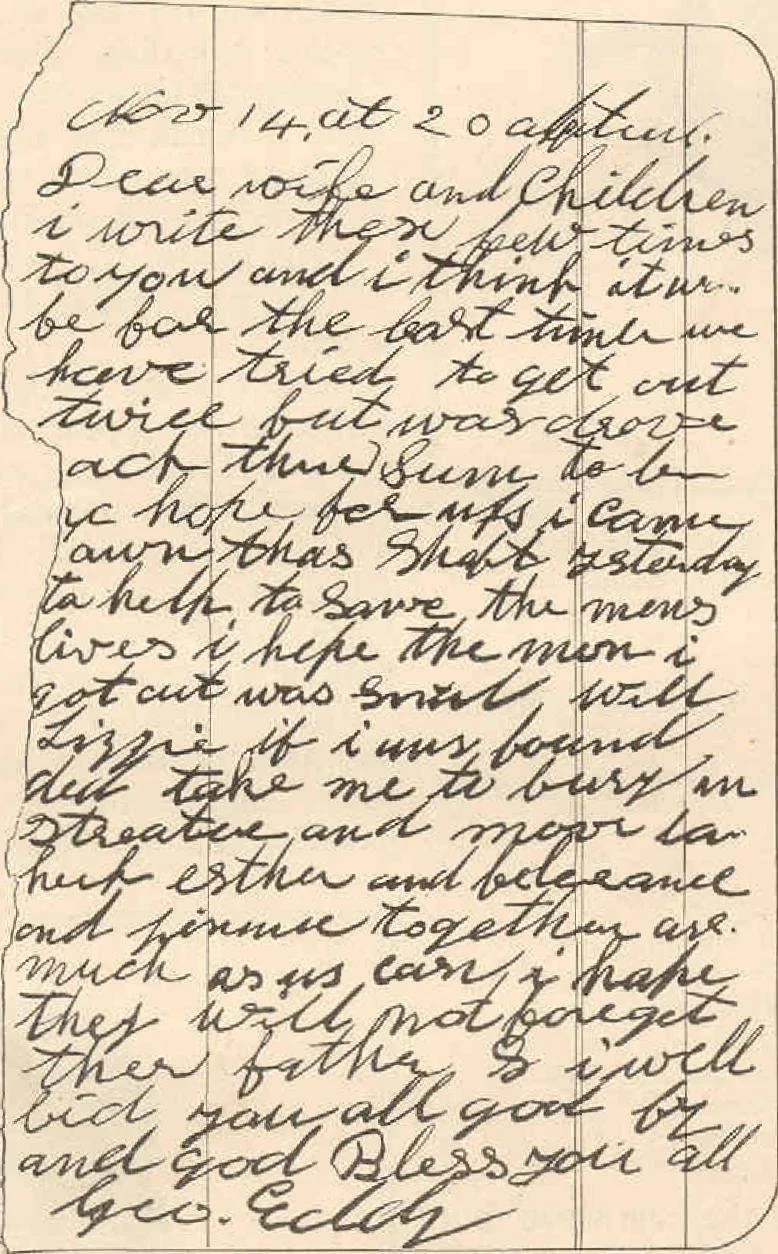

The Miracle of November 20th

Kenny's fire suppression work was creating conditions that would soon enable the impossible. While his men fought flames on multiple fronts, other rescue teams with oxygen equipment were slowly penetrating deeper into the mine.

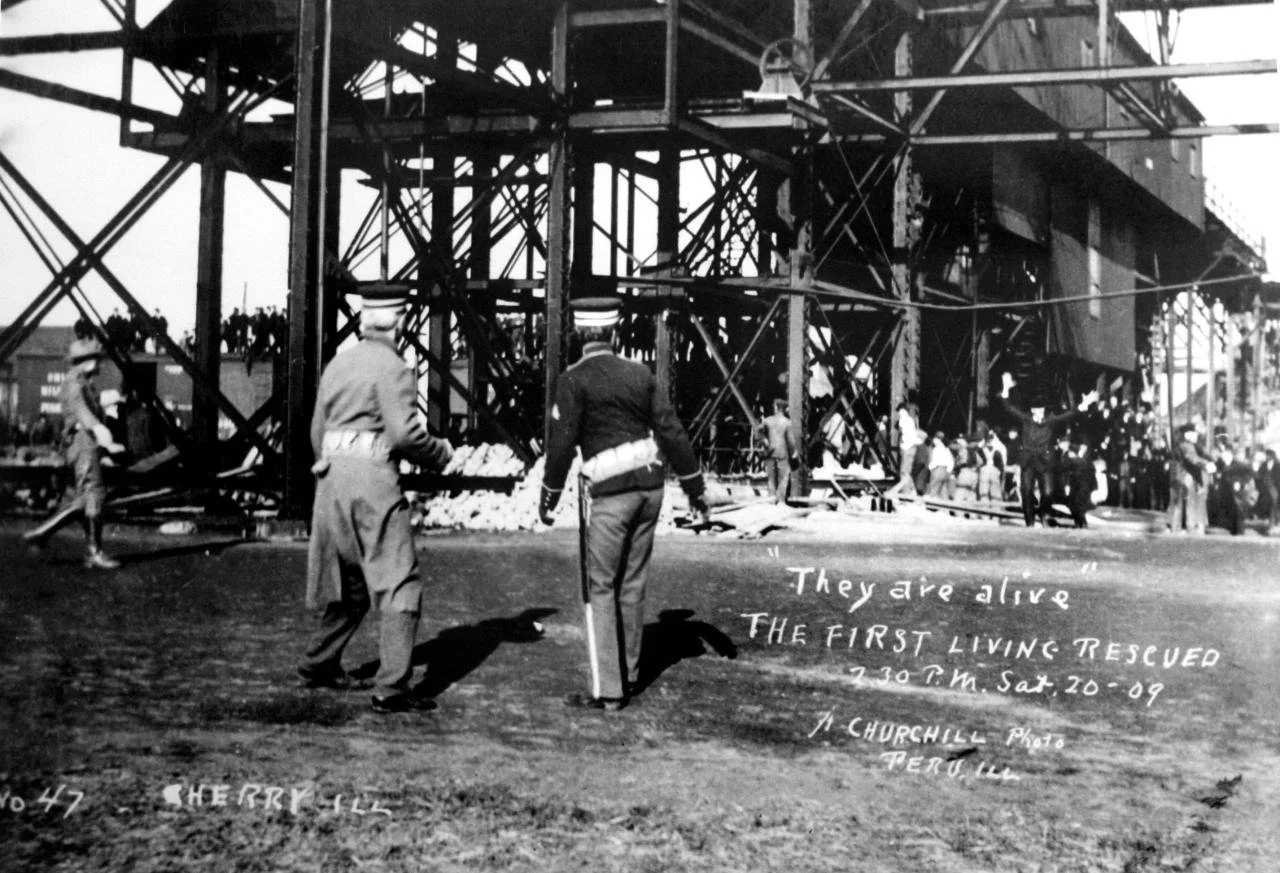

On Saturday, November 20th—exactly a week after the disaster—rescue teams led by mine superintendent David Powell made an astounding discovery. Following faint voices in the darkness, they found 21 miners who had survived eight days entombed underground.

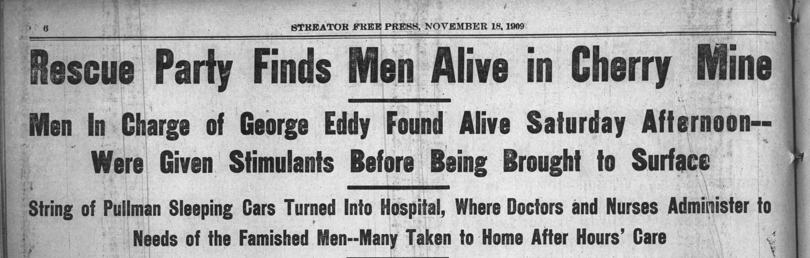

The Streator Free Press captured the moment with its banner headline: "Rescue Party Finds Men Alive in Cherry Mine." These men, led by miner George Eddy, had barricaded themselves in a remote section of the mine, surviving on minimal water and increasingly poisonous air.

Their rescue was only possible because Kenny's fire suppression work had contained the flames enough to allow rescue teams to penetrate the mine safely. Without the Chicago Fire Department's technical expertise in fighting the underground blaze, these men would never have been reached alive.

The miraculous moment: rescue workers bring the first survivors to the surface after eight days underground.

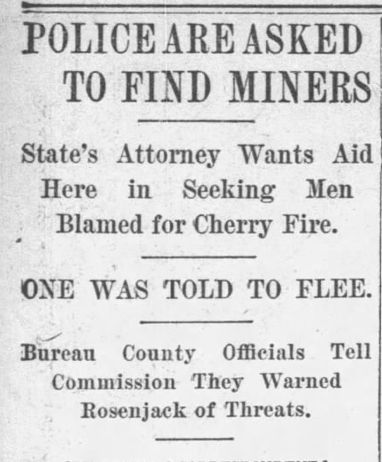

Contemporary newspaper coverage documents the Cherry Mine disaster from initial tragedy to miraculous rescue. These headlines show how Captain Kenny's fire suppression work helped enable the discovery of 21 survivors after eight days underground - one of the most remarkable mine rescues in American history.

"My Boys Were Brave"

Kenny's pride in his men was evident throughout his account. "My boys are brave boys and when told to go anywhere they went without one word," he wrote. "All their lives, like myself, they have been face to face with death and its agent—fire—and never retreated."

One of his firefighters, working with mine rescuers, penetrated over 1,200 feet into the mine's depths, farther than many thought possible. When the La Salle fire engine crew had to change water tanks, Kenny's men held their positions even as flames shot up the air shaft with renewed intensity.

"Not one man held back in the least," Kenny recorded. "My boys were brave and willing to take any chance."

The Streator Free Press of November 25th reported that the Chicago firemen worked in shifts around the clock, many overcome by smoke and heat, yet continuing to fight: "String of Pullman Sleeping Cars Turned Into Hospital, Where Doctors and Nurses Administer to Needs of the Famished Men."

The Final Count

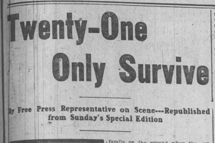

By November 22nd, the full scope of the tragedy was clear. The Times of Streator reported the grim mathematics under the headline "Twenty-One Only Survive." Of 484 men in the mine when fire broke out, 259 had perished. Twenty-one were rescued alive (one died shortly after), making this both one of America's deadliest mine disasters and home to its most miraculous rescue.

Kenny's work was complete, but the implications would last far longer. Mine safety regulations would be transformed, firefighting techniques adapted, and industrial rescue protocols revolutionized based on lessons learned at Cherry.

A Hero's Legacy

Captain Thomas P. Kenny returned to Chicago after five days at Cherry, having helped fight one of the most complex industrial fires in American history. His detailed technical account, preserved in Buck's contemporary chronicle, stands as both historical record and testament to professional expertise under extraordinary pressure.

The Cherry Mine disaster marked a turning point in American industrial safety. The sacrifice of the twelve rescue heroes, the miracle of the twenty survivors, and the technical innovations pioneered by men like Kenny led to sweeping reforms in mine safety regulations and emergency response protocols.

For the families of Cherry—the widows, orphans, and survivors—Kenny and his men represented something precious: the knowledge that when disaster struck, skilled professionals would risk everything to help. In an age when industrial accidents were often met with resignation, the Cherry rescue showed what was possible when expertise, courage, and determination converged.

Kenny served 44 years with the Chicago Fire Department, but his five days at Cherry may have been his most important. In the depths of an Illinois mine, he and his men proved that technical knowledge and professional courage could make the difference between tragedy and miracle.

The town of Cherry rebuilt. The mine eventually reopened. But the story of Captain Thomas P. Kenny and his brave firefighters reminds us that heroes aren't just made in single moments of courage—they're forged through years of training, tested in crisis, and defined by their willingness to descend into hell itself to bring others back to the light.

Sources: F.P. Buck, "The Cherry Mine Disaster" (1910); Contemporary newspaper accounts from The Chicago Tribune, Streator Free Press, Herald News, and The Inter Ocean; Chicago Fire Department records.

“The Cherry Mine Disaster”

F.P. Buck's 1910 firsthand account "The Cherry Mine Disaster" preserved Captain Kenny's detailed testimony and remains the primary source for understanding the rescue operations.

About This Research

This account is based on Captain Thomas P. Kenny's firsthand testimony preserved in F.P. Buck's 1910 chronicle "The Cherry Mine Disaster," combined with contemporary newspaper coverage from multiple sources. Kenny's detailed technical account remains one of the most complete records of specialized firefighting operations during America's early industrial disasters.

Preserving Family History

Stories like Captain Kenny's remind us that our ancestors often played roles in significant historical events without fanfare or recognition. Many families possess letters, photographs, or oral histories that could illuminate important moments in American industrial, military, or social history.

If you're researching your own family's stories:

Check local newspaper archives through Newspapers.com or library microfilm collections

Contact historical societies in areas where your ancestors lived or worked

Examine contemporary sources like city directories, employment records, and official reports

Look for technical or professional accounts that might mention family members

Want to see these research methods in action? Discover how we validated Captain Kenny's story through contemporary newspaper sources, fire department records, and multi-generational family collaboration in our detailed Kenny Family Case Study: When Family Stories Meet Historical Documentation. This comprehensive analysis shows how professional genealogy research transformed a family legend into documented American history.

The Chicago Fire Department's response to Cherry demonstrates how individual expertise and professional courage can shape history during moments of crisis. Captain Kenny's five days in Illinois may represent the most important work of his 44-year career—not for the recognition it brought, but for the lives his technical knowledge helped save.

Connect with this story: Share your own discoveries of family members in historical events, or explore the industrial safety reforms that emerged from tragedies like Cherry. These stories connect us to the broader narrative of how American workplace safety evolved through individual acts of professional courage.

Historical photographs courtesy of Illinois State Archives and local historical collections. Newspaper research conducted through Newspapers.com historical database. Personal photograph of Captain Thomas P. Kenny from family collection.

© 2025 Storyline Genealogy. This research may be shared with attribution for educational and historical purposes.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY