The Hidden Years: Marriage, Crisis and the Same-Day Contract

Part 3 of the Louise Senécal series

October 6, 1667. Louise Senécal became Louise Guilbault at Notre-Dame-de-Québec, eleven days after stepping off a ship from France. She was 30 years old, illiterate, and married to a man who had failed twice to secure a bride.

What happened next would span twenty-six years, four children, a mysterious separation, a reconciliation, and a death that revealed just how quickly a grieving widower could move on.

1681 Census of New France, Petite Auvergne. Pierre Guilbault (29) and Louise Senécal (40): 1 rifle, 8 cattle, 30 arpents. The children are listed on the following page: Marie (13), Joseph (9), and Étienne (6). Their reconciliation after the 1679 separation is confirmed—they were among the most prosperous families in the settlement.

Building Something from Nothing

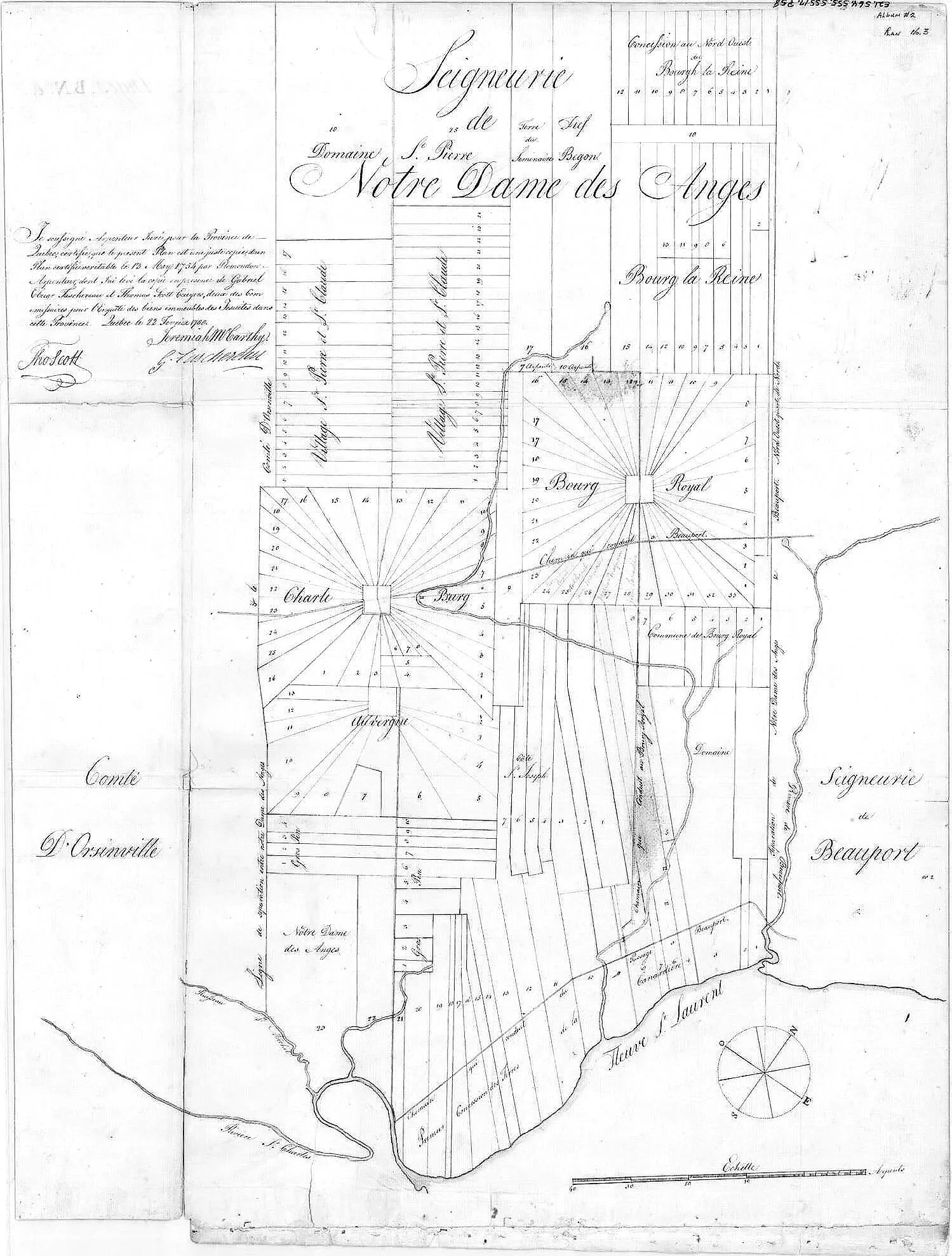

Pierre and Louise began with almost nothing. The 1667 census found them at Côte de Notre-Dame-des-Anges with two acres of cultivated land—probably an oral concession from the Jesuit fathers. Their neighbors were Jean Lemarché, known as Laroche, and Pierre Lefebvre. They owned basic farming tools, perhaps a cow, certainly hope.

Pierre wasn't just a farmer. Before marrying Louise, he had worked as a legal agent and debt collector. In 1657, aged only sixteen, he had been appointed attorney for Jacques Barbeau to collect 110 livres owed by a pottery merchant. The work took him across the colony and gave him contacts other settlers lacked.

This business acumen served them well. In September 1672, Pierre and his neighbor Olivier LeRoy signed a contract with Nicolas Follin, a Parisian investor "with his head full of projects, his hands white with gold-stitched gloves." Follin paid them 36 livres per acre to clear four acres of virgin forest. The work had to be completed by July 1673, with no more than six piles of branches and stumps per acre left for burning.

It was backbreaking labor. But it expanded their farm at someone else's expense while Follin enjoyed the cleared land for two years. When Follin disappeared from the colonial landscape—as so many investors did—Pierre and Olivier had doubled their cultivated acreage.

Louise bore three children during these early years: Marie in September 1668, Joseph-Olivier in March 1672, and Étienne in February 1675. Marie's godmother was Marie Britigny, wife of Denis Leclerc dit Lécuyer, suggesting the Guilbaults were forming connections within the Charlesbourg community.

Charlesbourg, 1667-1681. The Guilbaults began at Côte de Notre-Dame-des-Anges with 2 acres, later moved to Petite Auvergne with 30 acres.

The Crisis of 1679

December 17, 1679. Charlesbourg.

Louise stood before Abbé Charles Glandelet for her daughter's baptism. Elisabeth was just days old, her fourth child and second daughter. When the priest asked for the parents' names, Louise made a public declaration that would echo through the centuries.

She wasn't living with Pierre.

In 17th-century New France, this was extraordinary. Wives didn't leave their husbands. They certainly didn't announce marital separations at their children's baptisms, creating an official record of family breakdown.

What had gone wrong? The documents offer no explanation. By 1679, Pierre and Louise had been married twelve years. They had built a successful farm and established themselves in the community. Pierre was taking on substantial business ventures, like the three-year farming contract he signed with Olivier Morel, Sieur de La Durantaye, that same October.

Perhaps success itself was the problem. Pierre's contract with Morel involved managing two large farms with complex terms: providing livestock, cutting wood, delivering butter and pork. The responsibility was enormous. The financial risk was substantial. The time demands were crushing.

Or perhaps the problem was more personal. Louise was 42 when Elisabeth was born—old for childbearing by 17th-century standards. The pregnancy may have been difficult. The birth may have been traumatic. Four children in eleven years, combined with the physical demands of frontier farming, would have exhausted any woman.

What we know is this: sometime in 1679, Louise Guilbault decided she could no longer live with her husband. She made this decision public. And she kept her newborn daughter with her.

Elisabeth Guilbault's baptism, December 17, 1679. Louise publicly declared she was not living with Pierre—extraordinary for 17th-century New France.

The Reconciliation

The separation didn't last. By the 1681 census, Pierre and Louise were living together again in Petite Auvergne, a village of Charlesbourg. The census taker found them prosperous: thirty acres of cultivated land, eight horned cattle, two horses, one rifle. Of the ninety-six horses in all of New France, Pierre owned two.

They had reconciled, but Elisabeth was no longer with them. The little girl who had occasioned her mother's declaration of independence had died sometime between the 1679 baptism and the 1681 census. She was not quite two years old.

Did Elisabeth's death bring her parents back together? Did shared grief heal whatever had driven them apart? Or had they already been working toward reconciliation when tragedy struck?

The documents don't say. What they show is a family reunited and thriving. Pierre continued his business ventures, cutting firewood for Quebec tailors and managing the complex farming arrangements with Sieur de La Durantaye. Louise returned to the work of building their household and raising their surviving children.

The next twelve years were the most prosperous of their marriage.

The Final Years

By 1692, Pierre was planning for retirement. On September 7, he purchased a lot in Charlesbourg village: twenty-four feet by thirty-four feet on St-Nicolas Street. The purchase cost eighty livres, with an annual income requirement of ten livres. Pierre promised to build a house there and maintain a cedar palisade eight feet high between his property and the Jesuit fathers' cattle land.

Pierre wanted to be closer to the church and the merchants. At fifty-one, he was ready to step back from the intensive labor of farming. Louise was fifty-five, grandmother age in a society where most women died younger.

They had succeeded by any measure. From two acres and basic tools in 1667, they had built one of the most substantial farms in Charlesbourg. Their eldest daughter Marie had married François Dubois, a master mason from Poitou. Their son Joseph-Olivier, at twenty-one, was preparing for his own marriage and family.

Louise died on April 13, 1693, at age fifty-six. The cause isn't recorded. After twenty-six years of marriage—through separation, reconciliation, prosperity, and loss—she left behind an estate that included thirty acres of land, livestock, tools, household goods, and the village lot Pierre had purchased for their retirement.

She also left behind a husband who moved with shocking speed.

The Same-Day Contract

April 13, 1693. The day Louise died.

Pierre appeared before notary Louis Chambalon to sign a marriage contract with Jeanne Morin. She was twenty years old, daughter of the founding couple André Morin and Marguerite Moreau. Pierre was fifty-two and, as of that morning, a widower.

The timing was extraordinary. Either Pierre had been planning for Louise's death—suggesting she had been ill for some time—or he moved with breathtaking speed to secure his future. In a society where widowers often remarried quickly for practical reasons, this was remarkable even by colonial standards.

The contract was annulled. Perhaps Jeanne Morin had second thoughts about marrying a man who had signed papers on his wife's burial day. Perhaps her family intervened. Perhaps Pierre himself realized the impropriety.

On August 6, 1694, Jeanne Morin married Alexandre Biron in Charlesbourg. She was twenty-one years old and chose a man closer to her own age.

The Final Marriage

Pierre waited three more years. On January 3, 1697, guardianship was granted to his children—Marie, Joseph-Olivier, and Étienne—suggesting he was planning significant changes to his household arrangements.

Four days later, Pierre's plans became clear. On January 7, 1697, he married Françoise Leblanc at Saint-Charles church in Charlesbourg. She was twenty-two years old. He was fifty-six.

Françoise brought her own history of cancelled engagements. On October 24, 1694, she had annulled a marriage contract with Robert Faché. Perhaps she understood something about the complications of colonial courtship that others missed.

The marriage was witnessed by Thomas Pageau, Pierre Mortrel, and Julien and Jacques Leblanc. Priest Alexandre Doucet declared them united before God and man.

Nine months later, Pierre was dead.

Marriage record, January 7, 1697. Pierre, age 56, married Françoise Leblanc, age 22, at Saint-Charles church, Charlesbourg.

The End

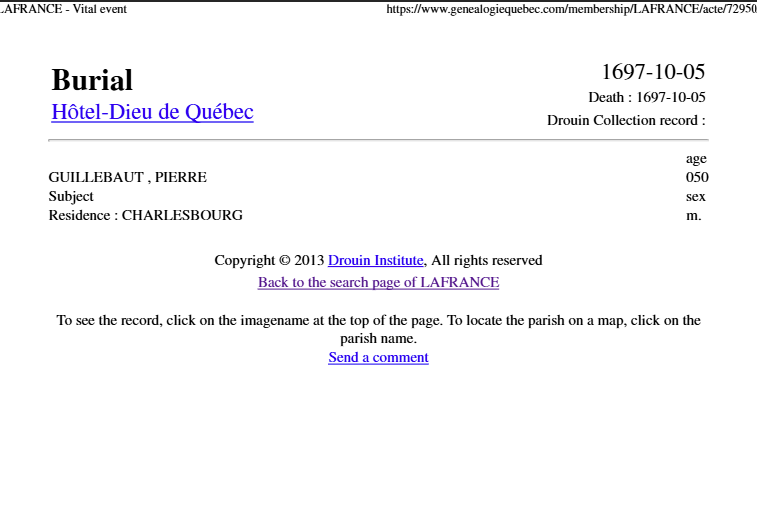

October 5, 1697. Hôtel-Dieu, Quebec.

Pierre Guilbault died at the hospital, perhaps age fifty-six. He had been married to Françoise for nine months. He left behind three adult children from his first marriage, a young second wife, and an estate that would require years of legal proceedings to settle.

The man who had failed twice to marry before Louise, who had signed a marriage contract the day she died, who had remarried at fifty-six and died within the year, was buried the same day he passed away.

His legacy was more complex than his dramatic final years suggested. Pierre and Louise had built something substantial from nothing. They had survived the challenges that broke other colonial marriages. They had raised successful children who would establish their own families and multiply their lineage across Quebec.

By the time Pierre died, their son Joseph-Olivier had already married Marie-Anne Pageau and was raising his own family on cadastral lot 371 in Charlesbourg. The line continued. The legacy endured.

But the estate Louise had helped build became the center of a family war that would require judicial intervention. The children she had borne and raised refused to let their father erase her contributions. They forced him to court, endured his "aversion," and ultimately preserved her memory in the official record.

Louise Senécal died young by modern standards but old by the measures of her time. She had crossed an ocean, survived the wilderness, built a farm, raised children, and accumulated wealth that her descendants would fight to protect.

The fight itself became her monument.

Read the complete story of that legal battle in Part 1: The Aversion: A Family War Over a Fille du Roi's Estate

Read how Louise's journey began in Part 2: Crossing the Atlantic: How Louise Senécal Became a Fille du Roi

Death record, October 5, 1697. Pierre Guilbault died at Hôtel-Dieu hospital, Quebec, nine months after remarrying.

Sources

All events described in this essay are documented in primary sources:

"Genealogy of Pierre Guilbault," biographical compilation with citations to multiple notarial records, parish registers, and census documents

Estate inventory documents, January-February 1697, Notary Guillaume Roger (BAnQ)

Marriage contracts: Pierre Guilbault and Jeanne Morin, April 13, 1693; Pierre Guilbault and Françoise Leblanc, January 7, 1697 (BAnQ)

Parish records: Elisabeth Guilbault baptism, December 17, 1679, noting Louise's separation declaration

1681 Census of New France, Charlesbourg district

Death records: Pierre Guilbault, October 5, 1697, Hôtel-Dieu, Quebec (PRDH)

Gagné, Peter J. King's Daughters and Founding Mothers, Volume 2

Louise Senécal is estimated to have between 210,000 and 630,000 living descendants in Quebec today. Her genetic lineage appears in genealogical databases spanning twelve generations and over 2,000 documented marriages of her descendants.

The legacy continues: Joseph-Olivier Guilbault married Marie-Anne Pageau in 1694. Today, Louise Senécal has an estimated 210,000-630,000 descendants in Quebec.

This concludes the Louise Senécal series. Her story—from orphan in Rouen to pioneer matriarch whose estate required court intervention to settle—illustrates both the extraordinary opportunities and the harsh realities facing women in 17th-century New France.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER