Crossing the Atlantic: How Louise Senécal Became a Fille du Roi

Part 2 of the Louise Senécal series

Before the "aversion."

Before Judge Guillaume Roger had to personally intervene in a family dispute so toxic that normal legal proceedings couldn't contain it.

Before three adult children stood against their father in a Quebec courtroom, refusing to let their mother be erased.

There was a ship. And a woman with nothing to lose.

The route of the St. Louis de Dieppe, June-September 1667. Louise survived a 107-day crossing that claimed the lives of roughly 10% of passengers.

The Orphan from Rouen

Louise Senécal was baptized February 15, 1637, in the parish of Saint-Éloi in Rouen, Normandy. Her parents, Pierre Senécal and Françoise Campion, had married five years earlier in the same church. When Françoise died on December 27, 1645, Louise was eight years old.

What happened next? The records are silent.

For twenty-two years—from her mother's death in 1645 to her departure for New France in 1667—Louise vanishes from the documentary record. No marriage. No trade apprenticeship. No property transactions. Her three siblings remained in Rouen; their names appear in various parish and civil records throughout the 1650s and 1660s. But Louise left no trace.

She may have been in service to another family. She may have been waiting for an inheritance that never materialized. She may have been caring for her father, though no record of his death survives. What we know is this: at age 30, Louise Senécal decided to cross an ocean to marry a stranger.

She was six years older than the average Fille du Roi. Most of the "King's Daughters" were in their late teens or early twenties—young women with decades of childbearing years ahead of them. Louise, at 30, was approaching what 17th-century demographers considered the end of prime fertility.

But she had something younger women lacked: desperation born of limited options.

Louise Senécal, baptized February 15, 1637, Parish of Saint-Éloi, Rouen. After her mother's death in 1645, Louise disappears from records for 22 years.

The Protest She Didn't Sign

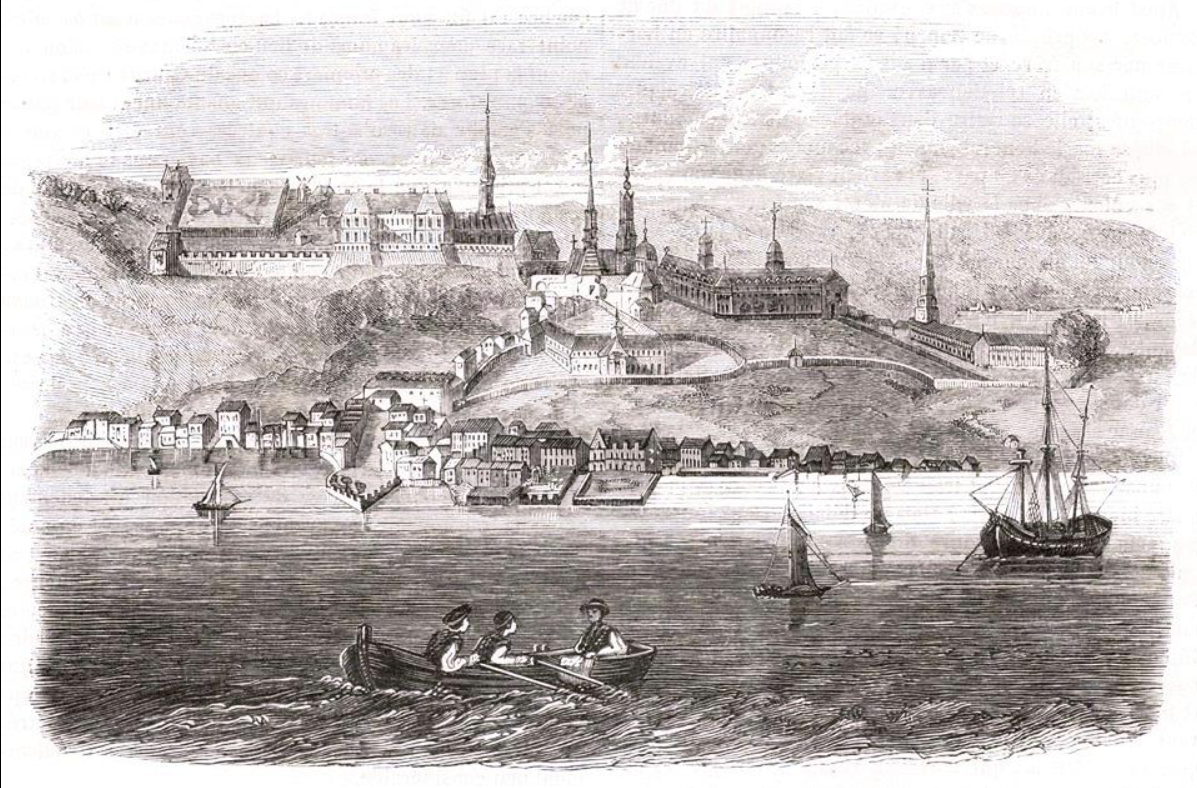

June 17, 1667. Port of Dieppe.

Twenty women filed a formal complaint against the officers of the ship St. Louis de Dieppe. The document—an "Acte de Protestation"—stated that the treatment planned for passengers showed "neither honesty nor humanity." They had seen the ship. They had met the crew. They wanted their objections on the legal record.

Louise Senécal's name wasn't among them.

Seven days later, on June 10, 1667, she boarded anyway.

What made her different? Was she braver than the women who protested? More desperate? More pragmatic? The documents don't say. What they do show is this: when other women looked at the St. Louis de Dieppe and recoiled, Louise Senécal saw possibility.

The ship carried ninety passengers: sixty-three Filles du Roi, twenty-seven indentured workers (engagés), fifteen horses, and crew. Louise found herself sharing cramped quarters with women from across France—some from Paris, others from smaller towns like herself. Among her shipmates were Catherine Basset, who would convert to Catholicism upon arrival, and Marie Albert, a Protestant who would keep her faith despite the pressures of New France.

They were not a homogeneous group united by shared background or circumstance. What they shared was the king's promise: passage to Quebec, a dowry, and the chance to build something from nothing.

Port of Dieppe, 1667. Twenty women filed formal complaints about conditions aboard the St. Louis de Dieppe. Louise Senécal wasn't among them.

107 Days at Sea

The crossing took fifteen weeks.

The St. Louis de Dieppe departed Dieppe on June 10, stopped at La Rochelle to collect additional passengers, then began the long Atlantic crossing. Historian Aimie Runyan describes typical conditions aboard ships carrying Filles du Roi: passengers received "nothing but a light meal in the morning and at night nothing for supper but a little hard tack." Disease was common—dysentery, scurvy, typhus. Ships routinely lost ten percent of their human cargo.

Louise survived when others didn't.

She endured the stench of overcrowded quarters shared with livestock. She watched one of the horses die en route and be thrown overboard. She listened to the complaints of sick passengers and the rough commands of sailors. She felt the ship pitch and roll through summer storms that sent everyone below deck for days at a time.

But she also witnessed something extraordinary: a community of women forming under impossible circumstances. Nobility and commoners, city dwellers and farmers, Catholics and Protestants—women who would never have spoken in France found themselves bound together by circumstance and hope.

When the cliffs of Quebec appeared on September 25, 1667, Louise had survived something that killed others. She had crossed an ocean based on a king's promise and her own courage.

Passenger manifest from the St. Louis de Dieppe, 1667. Louise's name appears among 63 Filles du Roi who made the crossing.

Five Days to Choose

Quebec in 1667 was a frontier town of fewer than 2,500 European inhabitants. The governor, Rémy de Courcelle, was fighting the Iroquois. The intendant, Jean Talon, was implementing the king's plans to populate New France. Bishop François de Laval was building the church that would dominate colonial society.

Into this small, precarious settlement stepped sixty-three women from the St. Louis de Dieppe.

Louise was met at the dock, likely by representatives of either the Ursulines or the Congrégation de Notre-Dame—the religious communities that helped settle arriving Filles du Roi. She was assigned temporary lodging. She was given a few days to meet potential husbands and make her choice.

Her choice was Pierre Guilbault.

Pierre was not Quebec's most eligible bachelor. Born around 1643 in the parish of Saint-Barthélemy in La Rochelle, he had immigrated to New France as a young man and settled in Charlesbourg. At 24, he was still unmarried—unusual for a colonial man his age.

More telling: he had tried twice before to secure a bride.

On November 8, 1665, Pierre had signed a marriage contract with Marie LeMoyne before notary Fillion. The marriage never happened. On July 10, 1667—just two and a half months before Louise's arrival—he had signed another contract with Marie Larteau before notary Gilles Rageot. That marriage, too, had fallen through.

Something about Pierre Guilbault made women—or their families—change their minds.

Quebec City, 1667. Population: 2,500. Louise had five days to choose her future.

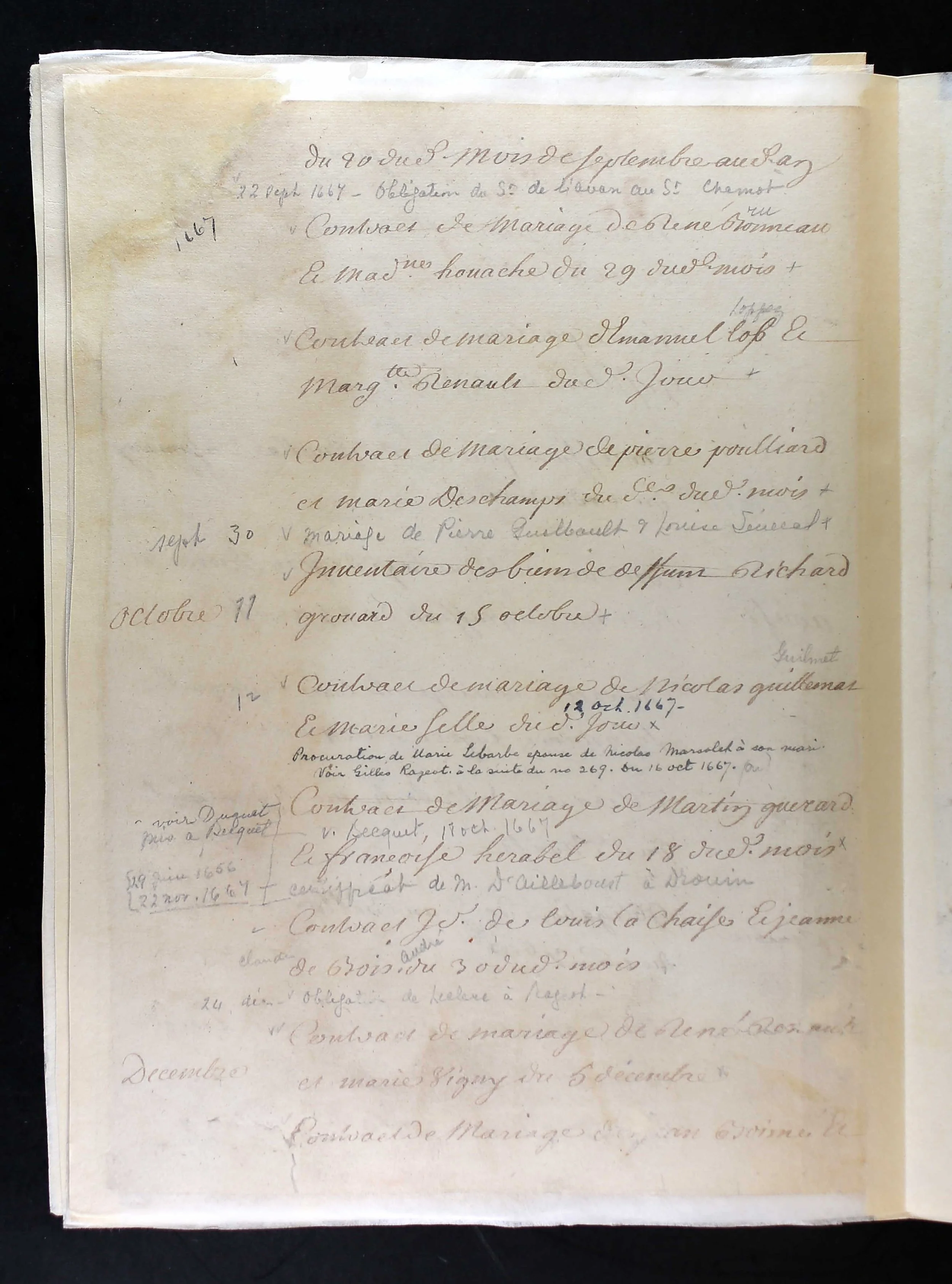

The Contract

September 30, 1667. Five days after stepping off the ship.

Louise appeared before notary Pierre Duquet in Quebec City. Beside her stood Pierre Guilbault, the man who had failed twice to marry in two years. The contract they signed specified a dowry of 100 livres—double the standard amount usually provided to Filles du Roi.

Why the generous dowry? Was it compensation for Louise's age? Recognition of Pierre's previous difficulties? An incentive to close a deal that had been pending too long? The contract doesn't explain.

What it does record is this: neither bride nor groom could sign their names. Louise Senécal—who had lived thirty years in Rouen, one of France's major commercial centers—was illiterate. Pierre Guilbault, who had attempted marriage twice before, couldn't write either.

Notary Duquet witnessed their marks and recorded the terms.

Marriage contract between Pierre Guilbault and Louise Senécal, September 30, 1667. Neither could sign their names. Notary Pierre Duquet witnessed their marks.

Eleven Days

October 6, 1667. Notre-Dame-de-Québec.

Louise Senécal married Pierre Guilbault eleven days after disembarking from the St. Louis de Dieppe. She was 30 years old, though the marriage record lists her age as 24—a discrepancy that reveals Louise's pragmatic survival instincts. Perhaps she lied to seem more marriageable. Perhaps the priest made an error. Or perhaps Louise Senécal—who had survived warnings about ship conditions, who had boarded anyway, who had chosen a man who'd already failed twice—understood that strategic misrepresentation sometimes served everyone's interests.

The wedding was likely witnessed by Bishop Laval himself, the most powerful man in New France after the governor and intendant.

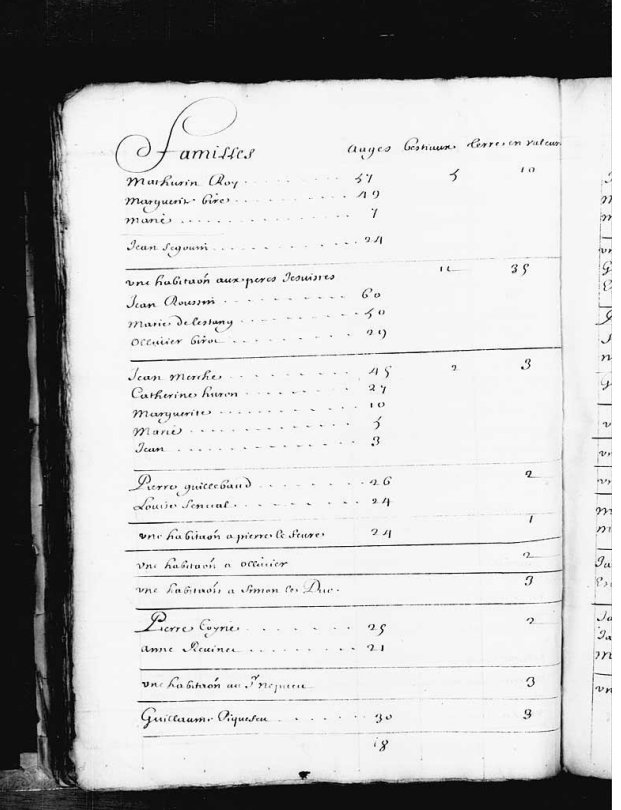

That same day—possibly within hours of the ceremony—census takers arrived at their door. The 1667 census records Pierre Guillebaud, 26; Louise Senécal, 24; 2 arpents under cultivation. From this modest beginning, they would build something remarkable.

Louise, the orphan from Rouen who had waited thirty years to marry, became Louise Guilbault of Charlesbourg. She had survived a crossing that killed one in ten. She had ignored warnings that sent twenty women fleeing. She had married a man who had already failed twice.

Whether this made her brave, desperate, or simply pragmatic, the documents don't say.October 6, 1667. Notre-Dame-de-Québec.

1667 Census of New France, taken possibly the same day as Pierre and Louise's wedding. Pierre Guillebaud (26), Louise Senécal (24), 2 arpents under cultivation. From this humble beginning at Côte de Notre-Dame-des-Anges, they would build one of Charlesbourg's most prosperous farms.

Source: Library and Archives Canada, Recensement du Canada, 1667

What Came Next

Over the next twenty-six years, Louise and Pierre built something remarkable.

They cleared land in Charlesbourg and built a farm. They raised four children: Marie (1668), Joseph-Olivier (1672), Étienne (1675), and Elisabeth (1679). They survived a marital separation in 1679—documented when Louise publicly declared she wasn't living with Pierre at their youngest daughter's baptism—and reconciled by the 1681 census, which shows them together again.

By 1693, they had accumulated thirty arpents of cultivated land, eight cattle, two horses, and substantial property. By frontier standards, they had succeeded.

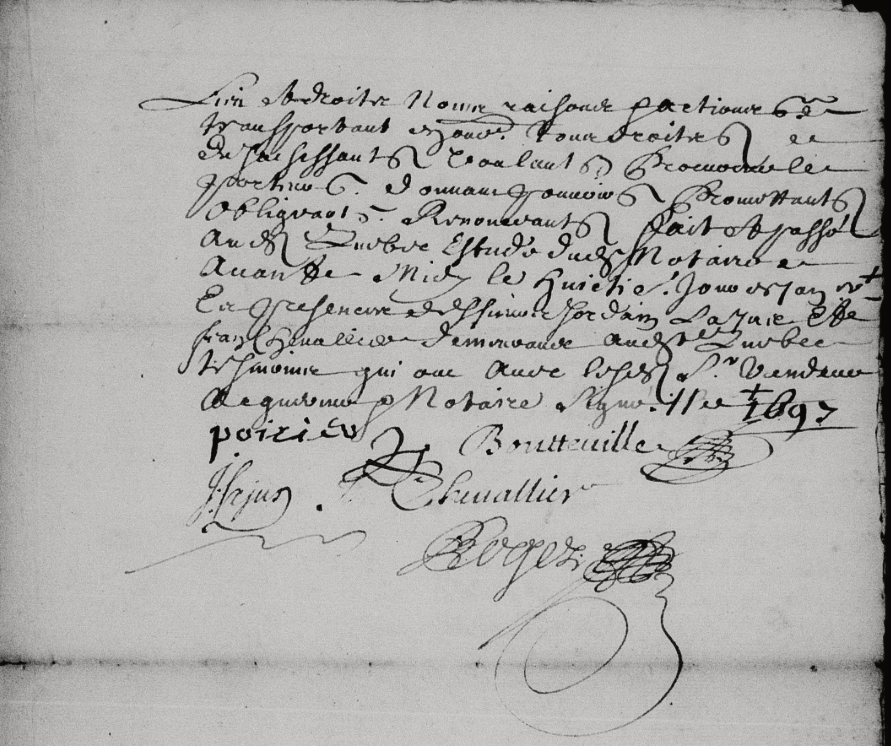

Louise died on April 13, 1693, at age 56. The inventory of her estate, formally closed on February 1, 1697, listed everything: every field, every cow, every building, every tool she and Pierre had accumulated over twenty-six years.

Estate inventory closure, February 1, 1697. Four years after Louise's death, the family war over her legacy was just beginning.

But listing what existed was easier than dividing it.

Pierre wouldn't cooperate. Despite court orders, despite his own children standing before him demanding their mother's legacy, he refused to settle the estate. For nearly four years, he kept everything Louise had helped build.

By late 1696, Pierre was planning to remarry—this time to Françoise Leblanc, a younger woman from a respectable Charlesbourg family. His children—Marie (now married to François Dubois for eight years), Joseph (married two years to Marie Anne Pajot), and Étienne (21, still legally a minor)—realized they had to act.

On January 7, 1697, Pierre took two strategic actions. He emancipated Étienne, freeing his youngest son from legal minority and allowing him to join his siblings in court. And on that same day, he married Françoise Leblanc.

The timing wasn't coincidence. It was strategy.

Seventeen days later, his three children filed suit.

That legal battle—extraordinary even by 17th-century standards—required Judge Guillaume Roger to write a word that changed everything: "aversion." The hostility between Pierre and his children was so severe, so mutual, so palpable that normal legal proceedings couldn't contain it.

Read the complete story in Part 1: The Aversion: A Family War Over a Fille du Roi's Estate

Coming in Part 3: The Hidden Years—the mysterious 1679 separation, the reconciliation, and twenty-six years of marriage that built a legacy worth fighting for.

Sources

All events described in this essay are documented in primary sources held by the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ), Library and Archives Canada, and available through FamilySearch and other genealogical databases:

Primary Sources:

1667 Census of New France: Pierre Guilbault and Louise Senécal household. Library and Archives Canada, Recensement du Canada, 1667, MG1-G1, volume 460, microfilm C-2477. Available online: https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/Home/Record?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=2318857&ecopy=e001342721

1681 Census of New France: Pierre Guilbault household, Petite Auvergne, Charlesbourg. Library and Archives Canada, Recensement du Canada fait par l'intendant Du Chesneau, 1681, MG1-G1, volumes 460/1 and 460/3, microfilms C-2474 and F-765

Marriage contract: Pierre Guilbault and Louise Senécal, September 30, 1667, Notary Pierre Duquet. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

Marriage record: Pierre Guilbault and Louise Senécal, October 6, 1667, Notre-Dame-de-Québec. Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH)

Passenger manifest: "Le St Louis de Dieppe 1667, Migrations." Geni genealogical database

Estate inventory documents: January 4 - February 1, 1697, Notary Guillaume Roger. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

Secondary Sources:

Gagné, Peter J. King's Daughters and Founding Mothers: The Filles du Roi, 1663-1673, Volume 2. Pawtucket, RI: Quintin Publications, 2001. ISBN: 1-55521-271-4

Runyan, Aimie Kathleen. "Daughters of the King and Founders of a Nation: Les Filles du Roi in New France." Master's thesis, University of North Texas, 2010

Biographical compilation: Pierre Guilbault genealogical notes with citations to multiple notarial records, parish registers, and census documents

Louise Senécal was one of 768 Filles du Roi who immigrated to New France between 1663 and 1673. According to genealogist Peter J. Gagné, Louise left an estimated million descendants. Today, thousands of French Canadians descend from Louise Senécal through her son Joseph-Olivier Guilbault (1672-1738).

This is part of an ongoing series documenting the lives of Filles du Roi through primary sources. If you're researching your own Fille du Roi ancestor and have questions about accessing 17th-century Quebec records, reach out—I'm happy to help.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER