The Aversion: A Family War Over a Fille du Roi's Estate

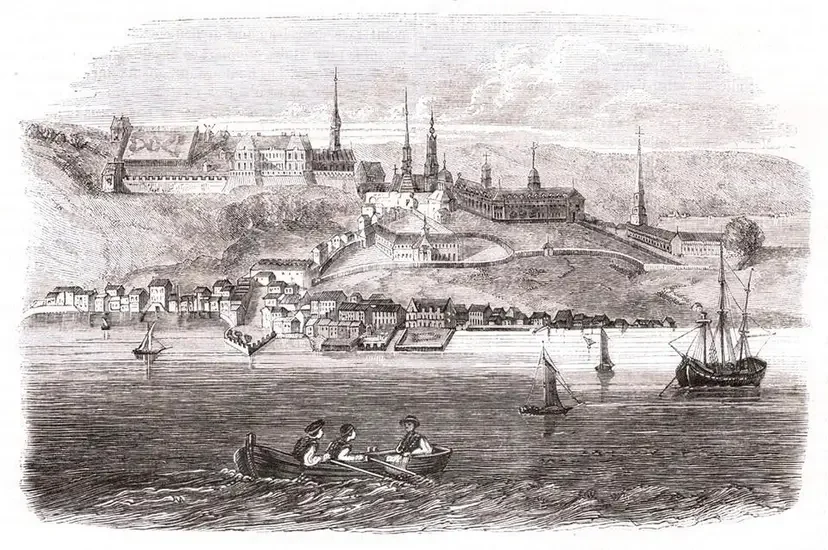

Quebec City in the 1690s, where a family's private war became public record

How a 17th-century court battle revealed a family torn apart by grief, greed, and a dead woman's legacy

On February 28, 1697, in a courthouse in Quebec City, Provost Judge Guillaume Roger wrote a word that changed everything: "aversion."

“Aversion—mutual repulsion, hostility so severe the court had to acknowledge it couldn’t proceed normally”

He wasn't describing a mild disagreement. He was documenting something far more serious—a hostility so severe, so mutual, so palpable that normal legal proceedings couldn't work. The parties couldn't be in the same room. They couldn't negotiate. They could barely speak to each other without erupting.

Who were these people who hated each other so intensely that a 17th-century judge had to use such extraordinary language?

A 52-year-old widowed farmer named Pierre Guilbault. And his three adult children: Marie (29), Joseph (25), and Étienne (22).

What were they fighting over?

Their dead mother's estate.

Her name was Louise Senécal, and she'd been dead for nearly four years. But the battle over what she'd earned, built, and left behind had just begun.

The Woman at the Center

Louise Senécal arrived in Quebec City on September 25, 1667, aboard a ship called the St. Louis de Dieppe. She was thirty years old—older than most of the other passengers, who were young women in their late teens and early twenties. She'd survived the three-month Atlantic crossing, weathered complaints of poor treatment by the ship's officers, and landed in a frontier settlement of fewer than 5,000 European inhabitants.

She was a Fille du Roi—a "King's Daughter"—one of approximately 768 women sponsored by King Louis XIV to immigrate to New France and marry settlers. She came with nothing but a dowry of 100 livres (double the average) and whatever courage it took to cross an ocean to marry a stranger.

Eleven days after arrival, she married Pierre Guilbault.

Marriage record of Louise Senécal and Pierre Guilbault, October 6, 1667, Notre-Dame-de-Québec. Eleven days after crossing the Atlantic, Louise became a wife.

Over the next 26 years, Louise and Pierre:

Built a farm in Charlesbourg

Raised four children (Marie, Joseph, Étienne, and Elisabeth)

Survived a marital separation in 1679 (documented when Louise publicly declared she wasn't living with Pierre at their youngest daughter's baptism)

Reconciled by 1681 (census shows them together)

Accumulated 30 arpents of cultivated land, 8 cattle, 2 horses, and substantial property

“Our mother built this. Our mother earned this. Our mother matters”

By 1693, they were prosperous. By frontier standards, they'd succeeded.

Then Louise died on April 13, 1693, at age 56.

And everything fell apart.

(Read more about Louise's Atlantic crossing and arrival in Quebec in Part 2 of this series: "Crossing the Atlantic")

The Remarriage

Pierre didn't wait long. In April 1693—the same month Louise died—he signed a marriage contract with a woman named Jeanne Morin.

The marriage never happened. The contract says "sans suite"—no follow-through. We don't know why. Did Pierre change his mind? Did Jeanne? Did the children object? The records don't say.

What we do know is that for the next three and a half years, Pierre didn't settle Louise's estate. Under French law in New France, marriage created a "community of property"—everything the couple accumulated together had to be inventoried and divided when one spouse died. Half went to the surviving spouse; the other half was divided among the children.

But Pierre didn't divide anything. He just... kept it all. The land Louise helped clear. The cattle she helped raise. The house she'd lived in for 26 years. He controlled it, worked it, and refused to give his children their inheritance.

By late 1696, Pierre was planning to marry again. This time to Françoise Le Blanc, a younger woman from a respectable Charlesbourg family.

The children—Marie (now married to François Dubois for 8 years), Joseph (married 2 years to Marie Anne Pajot), and Étienne (21, still legally a minor)—realized they had to act.

(For the complete story of Louise and Pierre's 26-year marriage, including the mysterious separation of 1679, read Part 4: "The Hidden Years")

The children—Marie (now married to François Dubois for 8 years), Joseph (married 2 years to Marie Anne Pajot), and Étienne (21, still legally a minor)—realized they had to act.

April 13, 1693

Louise dies

↓

3 years, 9 months

Estate unsettled

↓

January 7, 1697

Pierre marries Françoise

Étienne emancipated (same day)

January 24, 1697

Children file lawsuit

February 28, 1697

"Aversion" order issued

October 5, 1697

Pierre dies

The Legal Strike

The timing of what happened next suggests careful planning.

January 3, 1697: Pierre was formally appointed guardian of Étienne, his youngest son. This was routine—fathers became legal guardians of minor children when mothers died. It gave Pierre complete legal control over Étienne's inheritance.

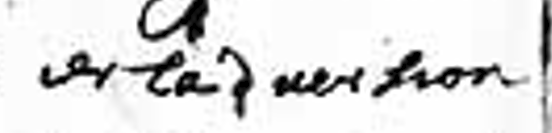

January 7, 1697: Two things happened on the same day.

First, Étienne appeared before the Sovereign Council of New France—the highest administrative body in the colony—and was granted emancipation. At 21, he was declared legally adult, freed from his father's guardianship, and able to act on his own behalf in court.

Second, Pierre Guilbault married Françoise Le Blanc.

Same day. The son freed himself from his father's control on the morning his father remarried.

This wasn't coincidence. This was strategy.

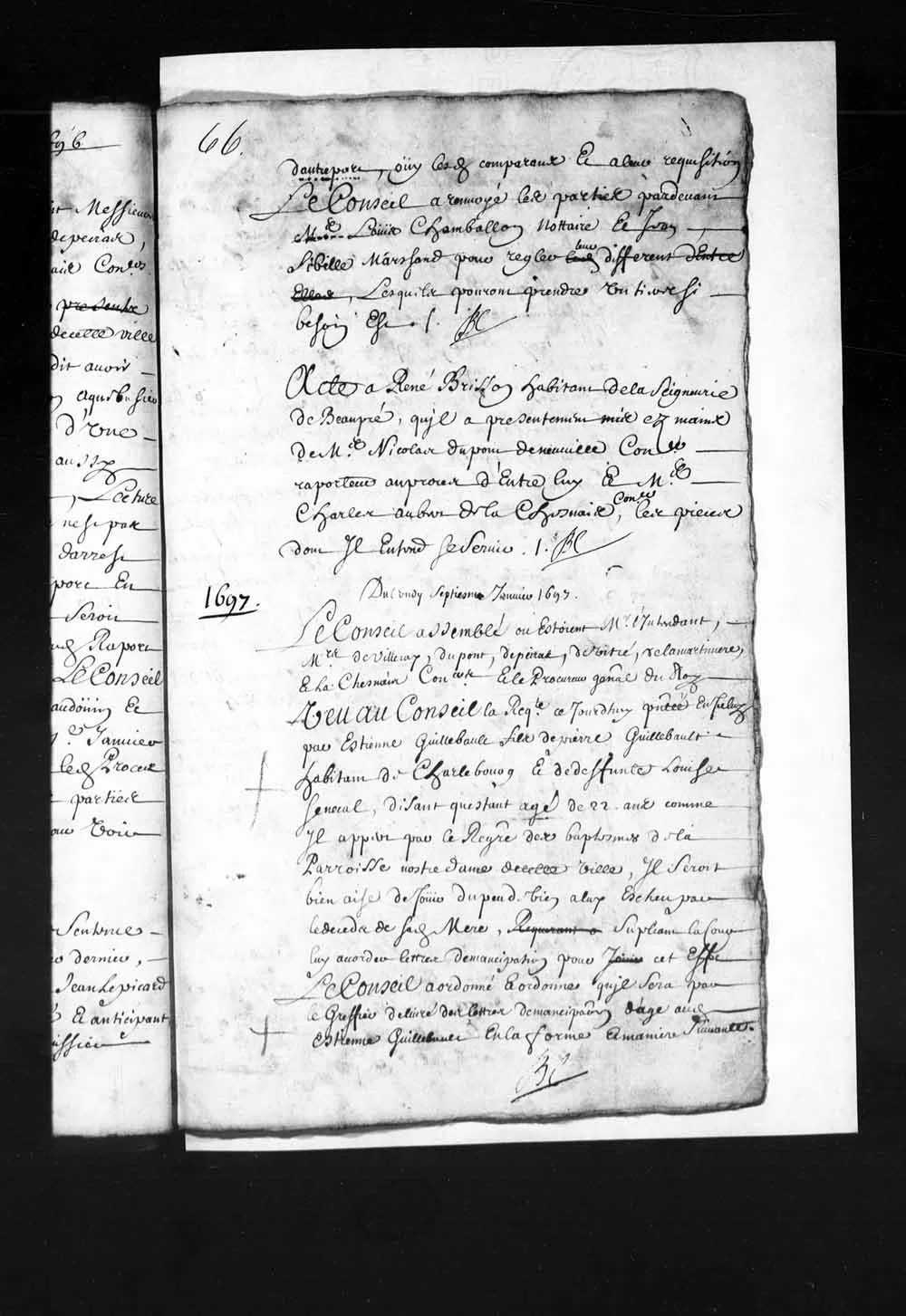

Letters of emancipation granted to Étienne Guilbault, age 22, January 7, 1697—the same day his father remarried. The Sovereign Council freed Étienne from Pierre's guardianship, allowing him to join the lawsuit. (Source: FamilySearch, Parish Records)

Pierre Guilbault's marriage to Françoise Le Blanc, January 7, 1697—hours after his son's emancipation. (Source: FamilySearch, Parish Records)

The timing was no coincidence. Same day, opposite intentions: one son freeing himself, one father remarrying .

January 24, 1697: Seventeen days after Pierre's wedding, his three children filed suit.

The petition named:

Joseph Guilbault

François Dubois, "comme ayant épousé Marie Guilbault" (as having married Marie Guilbault)

Étienne Guilbault

All three, the document stated, were "héritiers de Pierre Guilbault et de la défunte Louise Senécal"—heirs of Pierre Guilbault and the deceased Louise Senécal.

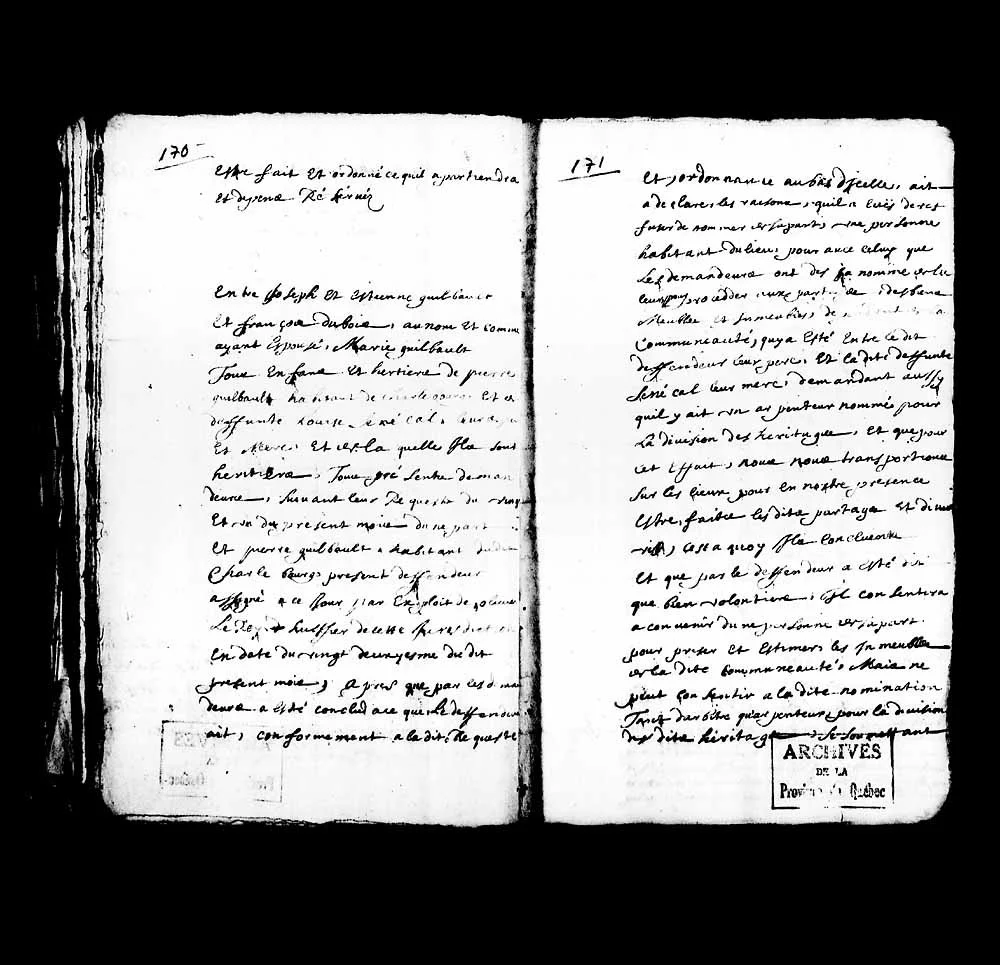

They asked the court to force Pierre to close the inventory of his mother's estate and divide the property. Judge Guillaume Roger issued an order: Pierre must comply.

February 1, 1697: Pierre appeared with his children and formally closed the inventory. Present were Pierre, Marie, Joseph, Étienne, and Pierre Mortrel (a neutral guardian appointed to protect the children's interests).

The inventory listed everything. Every field, every cow, every building, every tool. Everything Louise and Pierre had built together over 26 years.

But closing the inventory only established what existed. They still had to divide it.

And that's when things got ugly.

The Aversion

Pierre wouldn't cooperate. Despite the court order, despite the inventory, despite his own children standing before him demanding their mother's legacy, he refused to divide the property.

Twenty-seven days later, Judge Roger had to escalate.

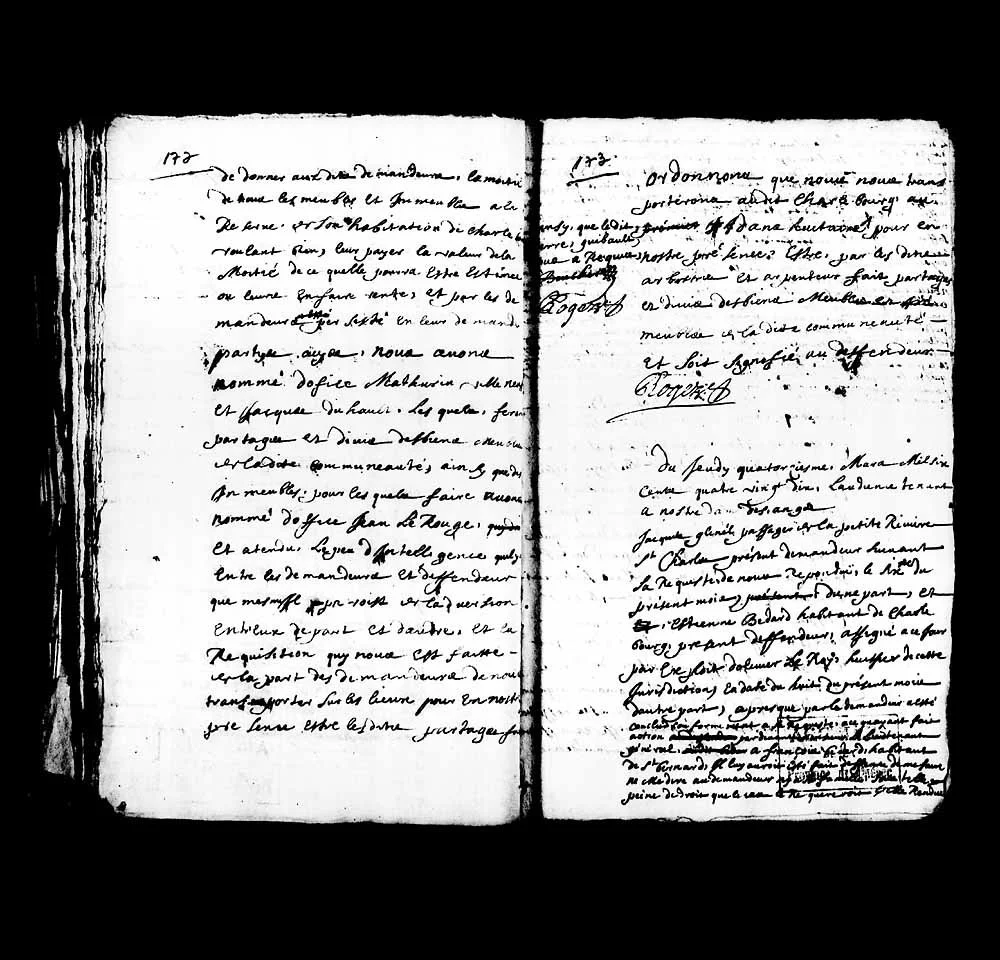

On February 28, 1697, he issued an extraordinary order. The language is formal, but the meaning is clear:

"Considérant l'aversion entre les demandeurs et défendeur..."

Translation Start of Folio 171:

This day, we, André Foucault, notary of the seigneury of the Island of Montreal, residing in the said place, undersigned,

there appeared in his person Guillaume Dubois, inhabitant of the said island, who, with the advice and consent of his relatives and friends,

Considering the aversion that exists between the plaintiffs and the defendant, and in order to prevent the inconveniences that could result from a longer continuance together in their shared life…

The word that changed everything: 'aversion.' February 28, 1697, Judge Roger documented hostility so severe he had to personally intervene. This document is extraordinary for its emotional language in what should be routine legal proceedings. (Source: BAnQ 03Q,TL5,D2769-119)

Considering the aversion between the plaintiffs and defendant...

Aversion. Not disagreement. Not conflict. Aversion—mutual repulsion, hostility so severe the court had to acknowledge it couldn't proceed normally.

The judge ordered:

He would personally travel to Pierre's home in Charlesbourg

Three arbitrators would accompany him

They would divide the property on-site, under court supervision

Pierre and his children wouldn't have to negotiate—the court would decide for them

This was extraordinary. Courts didn't make house calls. Judges didn't personally supervise estate divisions. But the "aversion" was so severe, normal procedures wouldn't work.

Imagine that scene: a judge and three arbitrators arriving at a Charlesbourg farmhouse in late winter 1697. Pierre Guilbault, 52, married to his new wife Françoise for less than two months. His three adult children, glaring at him across land their mother helped clear. Everyone standing in the February cold while strangers divided cows, fields, and buildings.

All because a widow tried to remarry too fast and children refused to let their mother's work be forgotten.

Want more stories like this? Subscribe to receive primary-source genealogy research directly in your inbox. No spam, just extraordinary 17th-century women who deserve to be remembered.

What the Children Knew

From the children's perspective, this wasn't about greed. This was about justice.

They'd watched their mother:

Cross an ocean at 30

Marry a stranger

Bear four children

Survive a marital separation

Reconcile

Work the land for 26 years

Die at 56

They'd watched their father:

Try to remarry the month she died

Refuse to settle her estate for nearly four years

Marry another woman

Bring that woman into the house their mother built

They weren't going to let him erase her.

So they fought. Marie (through her husband François) organized the strategy. Joseph, the oldest son, lent his name to the petition. Étienne sacrificed his father's protection to gain his freedom.

They forced Pierre into court. They forced the inventory. They endured the "aversion." They got arbitrators appointed.

And they won.

The End

Pierre Guilbault died on October 5, 1697—seven months after the "aversion" order, nine months after marrying Françoise.

He died at the Hôtel-Dieu, Quebec's hospital. Not at home. Not surrounded by family. Whether he was estranged from his children at the end, we don't know. But the "aversion" documented in February suggests he died as he'd lived since Louise's death: at odds with the children she'd raised.

Did the estate get divided? Presumably yes—the court had ordered it, appointed arbitrators, and supervised the process. Joseph, Marie, and Étienne likely got their shares. Pierre's brief second wife, Françoise, became a widow after nine months of marriage.

Find a Grave entry for Louise Senécal, died April 13, 1693, age 56. Buried at Ancien cimetière 1er de Charlesbourg. The woman whose death sparked a four-year war. (Source: FamilySearch Find a Grave Index)

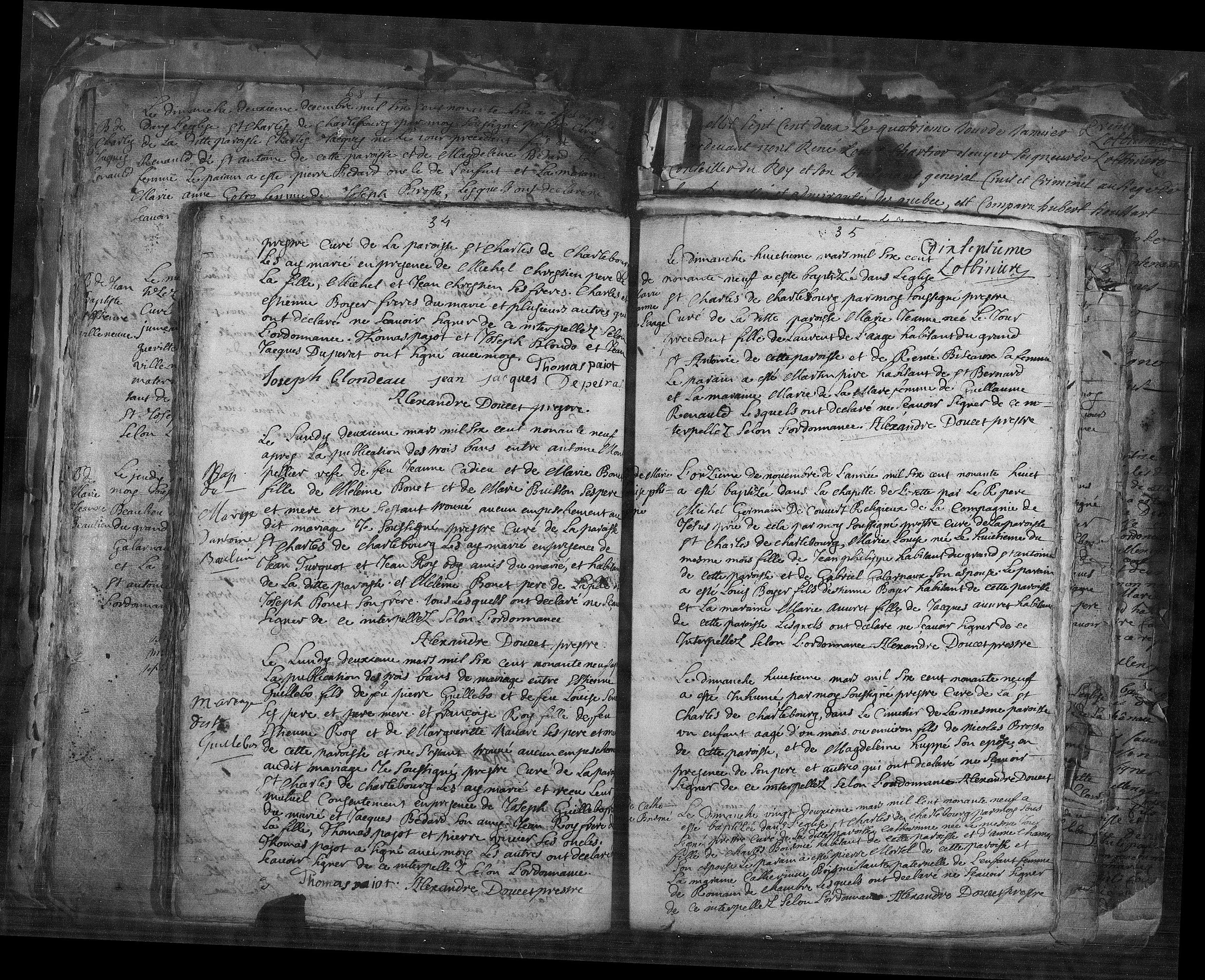

Étienne married in 1699—two years after his father died. His marriage record lists both parents as deceased: "feu pierre Guillebo" and "feu Louise Sen*." Both gone. The fighting over. The inheritance presumably settled.

He could finally start his own life.

Étienne Guilbault's marriage, March 2, 1699. Both parents listed as deceased: 'feu pierre' and 'feu Louise Sen*.' The fighting was finally over. (Source: FamilySearch, Parish Records)

What the Documents Reveal

The 1697 court battle over Louise Senécal's estate is extraordinary for what survived. We have:

The guardianship document (January 3)

The emancipation order (January 7)

Pierre's marriage record (January 7)

The petition (January 24)

The inventory closure (February 1)

The "aversion" order (February 28)

Pierre's death record (October 5)

Seven documents spanning nine months, creating a complete legal and emotional narrative of a family war.

This level of documentation is rare for 17th-century families, especially for ordinary habitants (farmers) rather than nobility or merchants. We usually get baptisms, marriages, deaths—vital records marking life's transitions. We rarely get court battles, emancipations, and judges writing about "aversion."

But here they are: official documents revealing not just dates and names but emotion. Anger. Betrayal. Strategic planning. Desperation. Justice.

And at the center of it all: Louise Senécal, a Fille du Roi who crossed an ocean in 1667, married in eleven days, raised four children, built a farm, died too young, and left behind children who loved her enough to fight for four years to honor her memory.

The Legacy

Louise never knew her grandchildren. She died before Joseph married, before Marie's children grew up, before Étienne found his wife.

But through Joseph's line, her descendants multiplied across Quebec and eventually spread west. One descendant, Pierre Guilbault (born 1710, Louise's grandson), lived to 86—witnessing the British Conquest, the American Revolution, and the reshaping of North America.

Today, thousands of French Canadians descend from Louise Senécal. She's in genealogical databases, family trees, and DNA.

But more than genetics, she left something else: three children who refused to let her be erased. Who went to court. Who endured the "aversion." Who forced their father to acknowledge that the property wasn't just his—it was hers too.

In 17th-century New France, women's work was often invisible. No wages. No recognition. No legal standing separate from their husbands.

But when Louise Senécal died, her children made her visible. They said: Our mother built this. Our mother earned this. Our mother matters.

And they made a judge write it down.

That's the aversion. That's the fight. That's the legacy of a Fille du Roi who came with nothing and left behind children who wouldn't let her be forgotten.

About the Documents

All events described in this essay are documented in primary sources held by the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ), Archives Nationales du Québec, and available through FamilySearch. The "aversion" order dated February 28, 1697 (BAnQ ref: 03Q,TL5,D2769-119) is reproduced in historical archives and includes the full text describing the extraordinary court intervention.

Louise Senécal was one of 768 Filles du Roi who immigrated to New France between 1663 and 1673. According to genealogist Peter J. Gagné, by 1729, Louise had 61 documented descendants. Today, estimates suggest millions of North Americans descend from the Filles du Roi collective, with Louise's line continuing through her son Joseph Olivier Guilbault (1672-1738).

This is part of an ongoing series documenting the lives of Filles du Roi through primary sources. If you're researching your own Fille du Roi ancestor and have questions about accessing 17th-century Quebec records, reach out—I'm happy to help.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER