Marie-Michelle Duteau dite Perrin: A Protestant Pioneer of New France

Marie-Michelle Duteau dite Perrin

One of the Brave 262

Before the King's Daughters. Before royal dowries and organized recruitment. Before the colony had a plan to populate itself with marriageable women. There were the Filles à marier—the marriageable girls who crossed the Atlantic on their own terms, signing contracts of indenture, leaving everything they knew for a wilderness they could scarcely imagine.

Marie-Michelle Duteau was one of approximately 262 such women. She arrived in 1658, five years before the official Filles du Roi program would begin. She received no dowry from the Crown. She enjoyed no royal protection. What she carried across the ocean was something more valuable: the courage to start over in a world where French was spoken but France was very far away.

She also carried something that made her unusual among New France's founding mothers: a Protestant baptism from the Huguenot stronghold of La Rochelle.

A Note on Names: Marie-Michelle appears in records under various spellings: Dutaut, Duteau, Dutost, Dutos. The "dite Perrin" acknowledges her mother Jeanne Perrin's family—a common French-Canadian naming convention. In this narrative, we use her full baptismal name Marie-Michelle as recorded by genealogist Peter J. Gagné, while acknowledging that most records simply call her "Marie."

La Rochelle: A Huguenot Stronghold

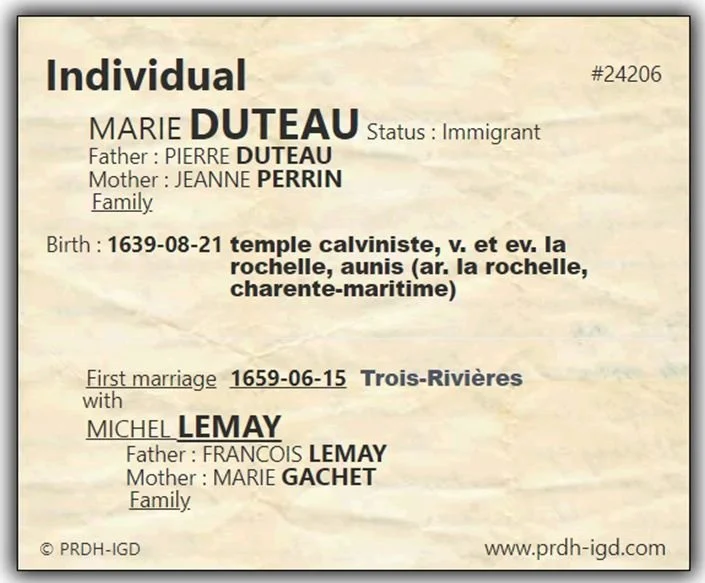

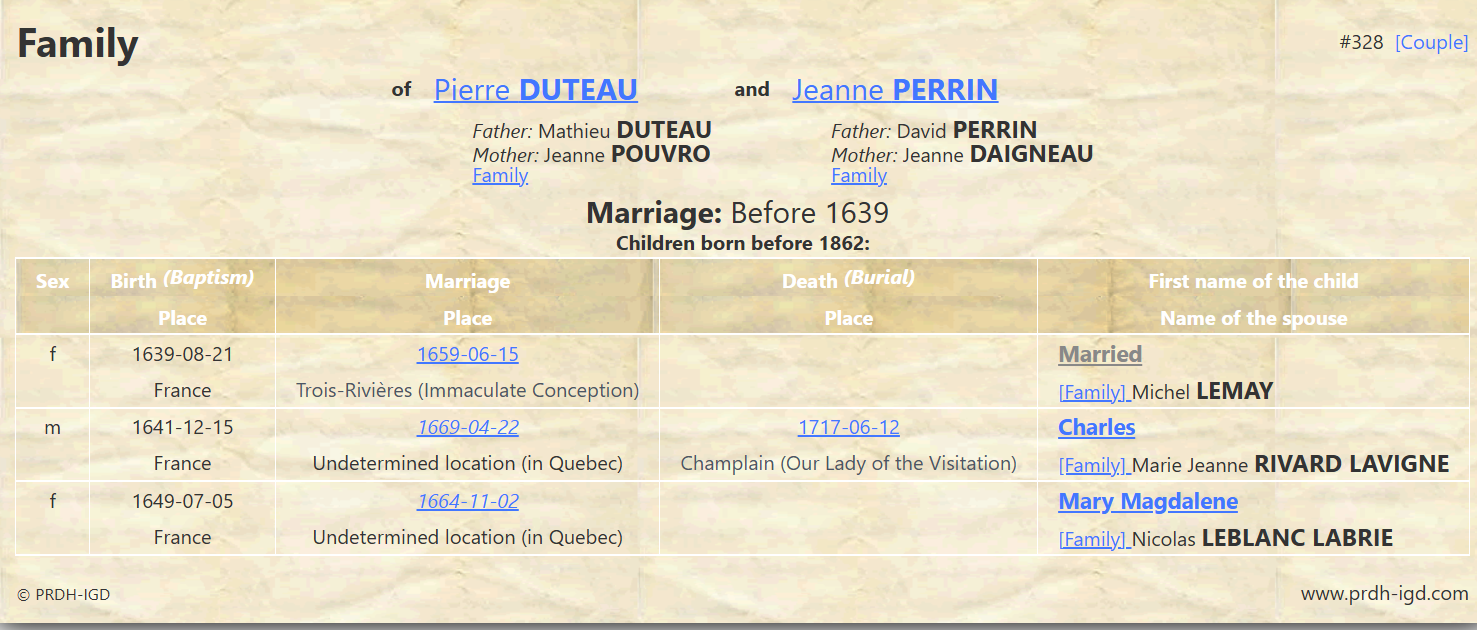

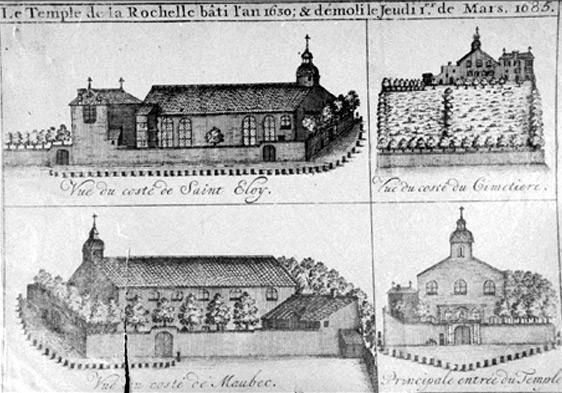

Marie was born on August 21, 1639, into a Protestant family in one of France's most famous Huguenot cities. La Rochelle had been the last great stronghold of French Protestantism, besieged by Cardinal Richelieu just eleven years before Marie's birth. The city's walls had fallen in 1628, but its Calvinist temples still stood—for now.

Four days after her birth, on August 25, Marie was baptized at the Temple Calviniste de la Villeneuve. This was not the grand temple that had once dominated the city's skyline, but one of the smaller meeting houses that survived the siege. It would stand until 1685, when Louis XIV's Revocation of the Edict of Nantes led to its demolition—ten years after Marie's death in the New World she would never have known what became of her birthplace of worship.

The Duteau Family of Saint-Nicolas

The Duteau family lived in the Saint-Nicolas district, the waterfront neighborhood named for the famous tower guarding the harbor entrance—the Tour Saint-Nicolas, protector of sailors and seafarers. It was here, amid the bustle of porters, fishermen, and merchants, that Marie spent her childhood.

Her father, Pierre Duteau, worked as a porter in the Catholic parish of Saint-Nicolas—one of the story's many ironies. After the siege of 1628, Catholicism had been restored to La Rochelle, and the Saint-Nicolas parish served the harbor community. Yet Protestant families like the Duteaus continued to live and work there, attending their own temples while earning their bread in Catholic institutions. This was the complex religious landscape of post-siege La Rochelle: Protestant children baptized in Calvinist temples, their fathers working in Catholic parishes, everyone navigating the uneasy peace that would hold until 1685.

Marie's mother, Jeanne Perrin, had been baptized in 1615, the daughter of David Perrin and Jeanne Daniau. The family was solidly Protestant, solidly working class, and about to be torn apart by circumstance and opportunity.

Marie had at least four siblings: her brother Charles, born in 1641; her younger sister Madeleine, born in 1649; and at least two other siblings. Of these, three would make the journey to New France with their mother. Their father—already ill—would stay behind, dying in December 1658, just months after his family sailed for Canada.

April 1658: A Family Divided

In the spring of 1658, the Duteau family made a decision that would scatter them across an ocean. Over two days in April, four members of the family appeared before Notary Teuleron in La Rochelle to sign contracts for passage to Canada.

It was a coordinated family emigration—mother and three children, leaving together but signing separate contracts based on their age and circumstances.

The ship that would carry them was the Prince Guillaume. The destination: Québec. The future: uncertain.

The Father Who Stayed Behind

But where was Pierre Duteau? He remained in La Rochelle. According to Peter Gagné's research, "he may have already been struck with a disease that claimed his life later that year." Pierre worked as a porter in the Catholic parish of Saint-Nicolas—an interesting detail for a man baptized Protestant, suggesting the religious complexity of life in La Rochelle after the great siege.

Pierre gave permission for his wife to take their youngest daughter to Canada. He signed no contract himself. He would never see his family again.

Pierre Duteau was buried on 12 December 1658 at the Calvinist temple in La Rochelle—eight months after his family sailed for New France. By then, his wife and children were somewhere in the wilderness of Canada, building new lives he would never witness.

The Mother Who Vanished

And Jeanne Perrin? She signed the most substantial contract of all—five years of service. She brought her youngest daughter. She crossed the Atlantic with her three children.

And then she disappeared.

According to the researcher Bersyl, Jeanne Perrin "left no trace of herself in New France." Whether she died during the crossing, shortly after arrival, or simply vanished from the records, we cannot say. The mother who organized this family emigration, who received permission from her dying husband, who signed a five-year contract to build a new life—she is a ghost in the archives.

But her children survived. All three would marry in New France. All three would have families. And two of them—Marie and Madeleine—would be counted among the rare Filles à marier.

Two Sisters, Both Filles à Marier

Marie-Michelle was not the only Fille à marier in her family. Her younger sister Madeleine—the nine-year-old who crossed the Atlantic clinging to her mother—grew up to become a Fille à marier herself.

This makes the Duteau family remarkable: two of the approximately 262 Filles à marier came from the same Protestant household in La Rochelle.

The Duteau Sisters

| Marie-Michelle Duteau | Madeleine Duteau |

|---|---|

| Born 21 August 1639 | Born 05 July 1649 |

| Emigrated age 19 | Emigrated age 9 |

| Married Michel Lemay, 15 June 1659 | Married Nicolas Leblanc dit Labrie, 2 Nov 1664 |

| 9 children | Children (number unknown) |

| Died c. 1675, age ~36 | Death date unknown |

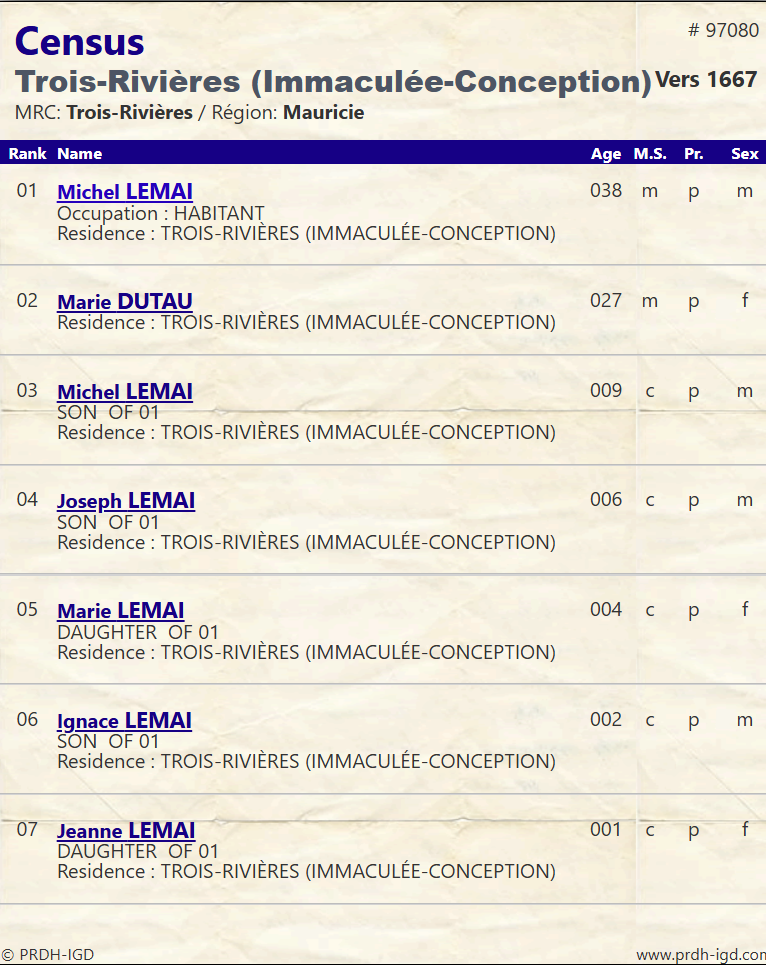

Their brother Charles also thrived. He married Jeanne Rivard on 22 April 1669 and settled at Champlain, where he lived until his death on 12 June 1717. The 1666 census shows him living with Marie and Michel's household—the siblings stayed close in those early years.

Three Protestant children from La Rochelle. A mother who vanished. A father who died before he could follow. And yet the family line continued—spreading across New France, converting to Catholicism, becoming part of the fabric of Québécois society.

June 15, 1659: A New Beginning

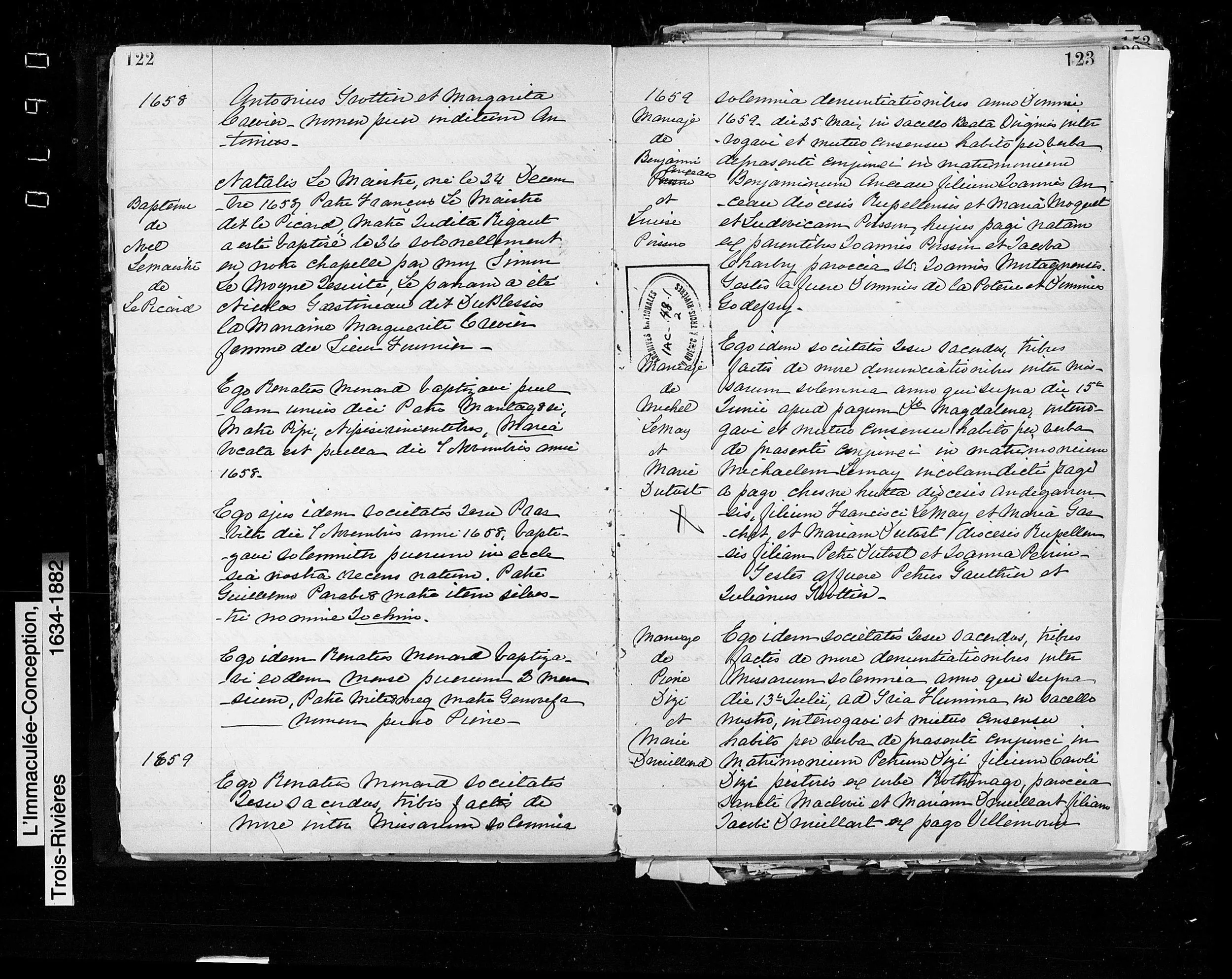

Less than a year after arriving in New France, Marie-Michelle stood before Father René Menard, S.J., in the chapel at La Magdeleine, near Trois-Rivières. Beside her was Michel Lemay, a 28-year-old colonist who had arrived from France six years earlier.

The marriage record, written in Latin, tells us what the couple likely didn't think to record themselves: that Marie was converting from the faith of her childhood. In Catholic New France, there was no other option. The Protestant girl from La Rochelle became a Catholic wife in the wilderness.

The witnesses were Petrus Gauthier and Julianus Riotteri. The groom's parents—François Lemay and Marie Gaschet—were an ocean away in France. The bride's father was dead, her mother had vanished, and her siblings were scattered across the colony.

And yet. A new family was beginning.

Pioneer Wife: 1659-1675

Marie and Michel's marriage would last sixteen years—not long by modern standards, but long enough to establish a dynasty. They would move three times, following the opportunities of the frontier, always pushing a little further into the wilderness.

Cap-de-la-Madeleine (1659-1669)

For their first dozen years together, Marie and Michel lived at Cap-de-la-Madeleine, where Michel worked as a carpenter and builder. In partnership with Elie Bourbeau, he constructed a chapel for Pierre Boucher—"of 20 feet in length by 20 feet in width"—and later transported it to Fort Saint-François to help build fortifications against Iroquois attacks.

The 1666 census captured a snapshot of their household: one servant named Pierre, four head of cattle, and 18 arpents of land under cultivation. By 1667, there were already children—the first of the nine who would survive to adulthood.

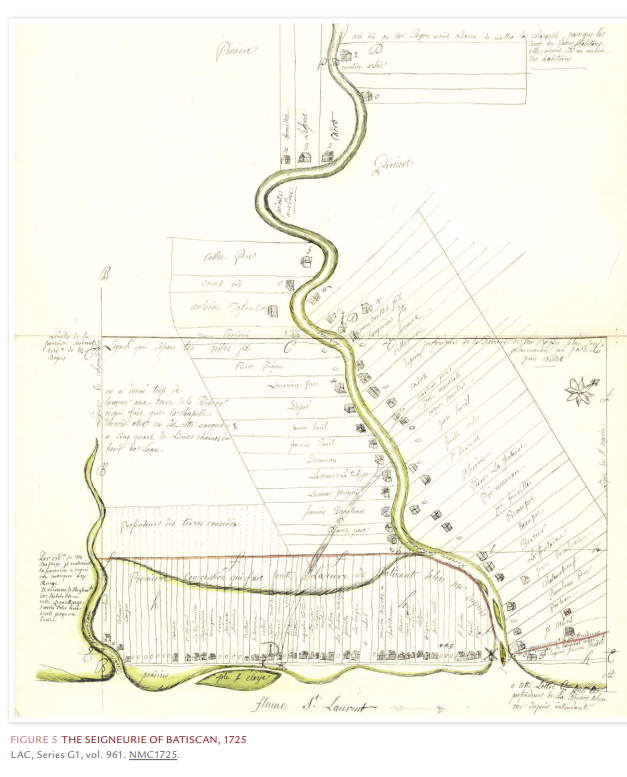

Batiscan (1669-1672)

In 1669, the family moved to Batiscan, where the Jesuits had offered Michel a concession. Here Marie's brother Charles was nearby—he had married Jeanne Rivard and was establishing his own family. The siblings who had crossed the Atlantic together were building parallel lives in the New World.

Lotbinière (1672-1675)

The final move came in 1672, when René-Louis Chartier received the Seigneurie of Lotbinière from Intendant Jean Talon. Michel obtained nine arpents of prime river frontage, and the Lemay family became the first to establish a home at Saint-Louis de Lotbinière.

It was here, at the edge of the settled world, that Marie would spend her final years. Michel had taken up eel fishing—a lucrative business that would eventually produce 60,000-70,000 eels in a good season. The family was prospering. The children were growing.

And then, around 1675, Marie-Michelle died. She was only 36 years old.

"Alas for the family, Marie-Michelle died around 1675. The exact date of her disappearance is not known and the only way we can approximate the period is through the inventory of her effects on 30 November 1675. In great sorrow, Michel sought to reorganize his rudderless home."

— Thomas J. Laforest, Our French Canadian Ancestors, Vol. IIMarie left behind nine children—the youngest, Marie-Madeleine, barely three years old. We don't know what killed her. Childbirth complications, illness, the harsh conditions of frontier life—the records preserve only the inventory of her possessions, not the cause of her death.

Michel's Second Marriage

On 12 April 1677, less than two years after Marie's death, Michel Lemay married Michelle Ouinville at Côte-Champlain. Michelle was a King's Daughter—one of the women who arrived under royal sponsorship between 1663 and 1673—and the widow of Nicolas Barabé, with whom she had four children.

Together Michel and Michelle had at least two children:

- Antoinette — born 8 March 1680 at Grondines; married François Girard in 1710

- Louis-François — baptized 2 March 1684 at La Perade; died 13 July 1696 at Hôtel-Dieu in Québec, age 12

Michel himself died at the end of 1684, possibly in a fishing accident—the records don't say. Michelle Ouinville remarried in November 1685 to Louis Montenu at Lotbinière; she died around 1700.

The children of both marriages grew up together at Lotbinière, bound by their shared father and the frontier life they all knew. Marie's nine children were old enough by 1677 to remember their mother—and to carry her legacy forward.

The World Marie Knew

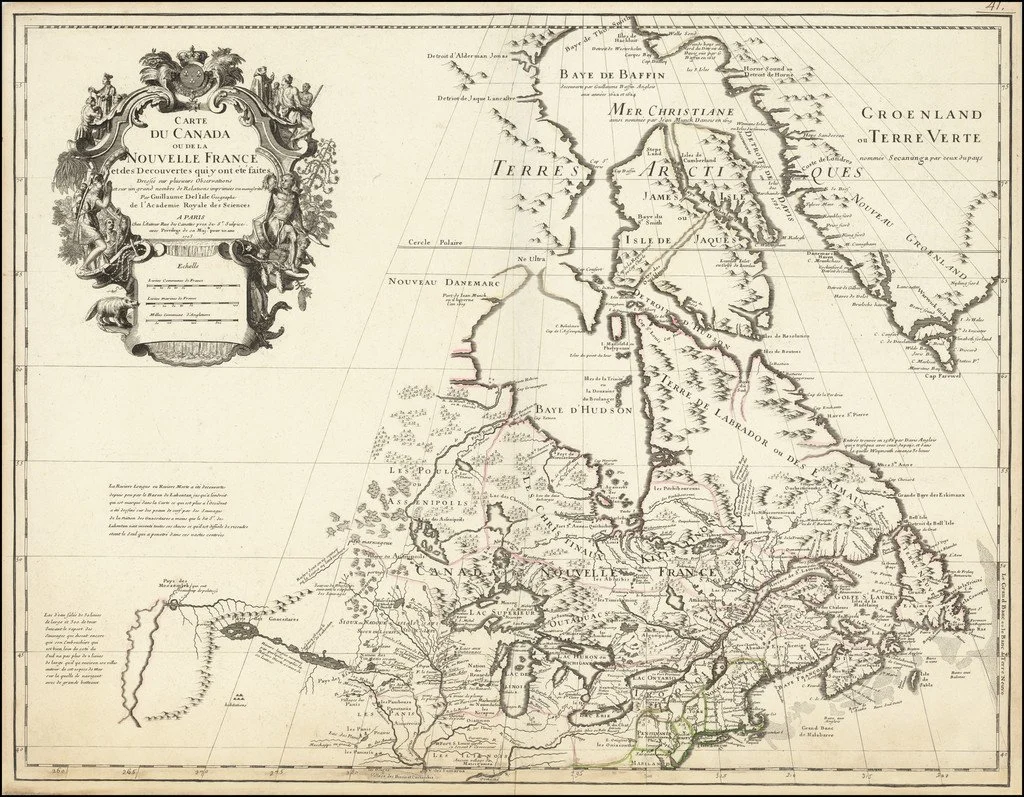

Marie-Michelle's journey took her from the Protestant stronghold of La Rochelle across the Atlantic to the frontier settlements along the St. Lawrence River. These maps help us understand the world she inhabited.

A Mother of Millions

Marie-Michelle was only 36 years old when she died, leaving behind nine children—the youngest, Marie-Madeleine, barely three years old. She never saw them marry, never held her grandchildren, never knew that her descendants would one day number in the millions.

| Child | Born | Married | Spouse | Legacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michel | c. 1660 | 1686 | Catherine Jobin | 8 children |

| Joseph | c. 1661 | 1686 | Agnès-Madeleine Gaudry | 10 children; took name "dit Delorme" |

| Marie | c. 1663 | 1685 | Louis Houde | — |

| Ignace | c. 1665 | 1687 | Anne Girard | 8 children; voyageur; took name "dit Poudrier" |

| Marie-Jeanne | c. 1666 | 1688 | Etienne DeNevers | — |

| Charles | c. 1669 | 1691 | Louise Houde | 5 children |

| Jean | c. 1670 | 1700 | Marie-Hélène Boucher | 8 children; took name "dit Larondière" |

| Pierre | c. 1671 | 1695 | Anne Germain | 5 children; voyageur |

| Marie-Madeleine | c. 1672 | 1695 | Claude Houde | — |

The Numbers Tell the Story

From this single Protestant girl who crossed the Atlantic in 1658, the PRDH database has traced:

- Between 2,030,000 and 2,450,000 descendants in Québec today

- 8,579 documented marriages over 13 generations

- Descendants in every Canadian province and across the United States

Marie-Michelle lived only 36 years. Her legacy has lasted nearly four centuries.

Michel Lemay dit Poudrier

Marie's husband deserves his own recognition. Born March 13, 1631, in Chênehutte-les-Tuffeaux, a village on the Loire known for its chalk quarries, Michel arrived in New France in 1653—during the height of the Iroquois Wars. He earned his sobriquet "Le Poudrier" (the gunpowder maker) as a militiaman defending Trois-Rivières.

Today, in his home village of Chênehutte-les-Tuffeaux, a memorial plaque commemorates his journey:

"MICHEL LEMAY

Originaire de notre village

partit en 1653 vers la

Nouvelle France 'QUEBEC'

où il fit souche."

He established lineage indeed. But he did not do it alone. Behind every ancestor who "fit souche"—who took root—there was a woman who made it possible. For Michel Lemay, that woman was Marie-Michelle.

Filles à Marier vs. Filles du Roi

Marie-Michelle is often grouped with the Filles du Roi—the King's Daughters who arrived between 1663 and 1673. But this is historically incorrect, and the distinction matters.

The Filles du Roi traveled under royal sponsorship. Their passage was paid. They received dowries of 50 to 100 livres. They were recruited, organized, and chaperoned.

The Filles à marier—like Marie—had none of this. They signed contracts of indenture, promising years of labor in exchange for passage. They traveled with their families or alone. They received no dowries, no royal protection, no guaranteed prospects.

They were, in many ways, braver. They were certainly rarer. And Marie was among the rarest of all: a Protestant in Catholic New France, one of perhaps a handful of Huguenot women among the founding mothers of Québec.

Document Gallery

A Protestant Pioneer Remembered

Marie-Michelle lived only 36 years. She left no letters, no diary, no portrait. What we know of her comes from a handful of documents: a baptism record in a Protestant temple that no longer stands, an indenture contract signed in a notary's office, a marriage record in a mission chapel, census records that tracked her growing family, and an inventory of possessions that marks her passing.

And yet she is everywhere. In the millions of Québécois who carry her DNA. In the family names—Lemay, Delorme, Larondière, Poudrier—that descended from her children. In the villages along the St. Lawrence where her grandchildren and great-grandchildren built farms and churches and communities.

She was one of 262 Filles à marier. One of perhaps a dozen Protestant women among them. One of the bravest, the rarest, the most essential founders of French Canada.

Marie-Michelle crossed an ocean at nineteen years old. She converted from the faith of her childhood to marry in the only church permitted in New France. She bore nine children in sixteen years. She died at thirty-six, in a settlement at the edge of the known world, her mother vanished, her father dead, her birthplace of worship soon to be demolished by royal decree.

But her descendants remain. Millions of them. And through them, the Protestant girl from La Rochelle lives on.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY