Marie Riton: A Fille à Marier in New France

Marie Riton

A Woman Between Worlds

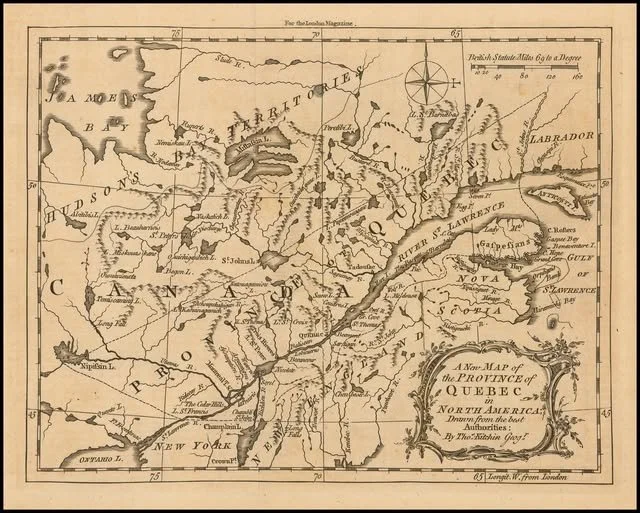

Marie Riton occupies a liminal space in the history of New France: a woman shaped by religious conflict, social vulnerability, and migration at a time when female settlers were both scarce and indispensable. Her life illustrates the realities faced by the earliest Filles à marier—women who immigrated before royal sponsorship formalized female settlement in the colony.

Unlike the later Filles du roi who received royal dowries and protection, Marie crossed the Atlantic with no state support, carrying instead the weight of an illegitimate birth and a formal Protestant conversion. That she transformed herself into a landholding matriarch at Beauport, mother of seven children whose descendants now number in the millions, speaks to a resilience that the documents only hint at.

Origins: Poitou, circa 1623

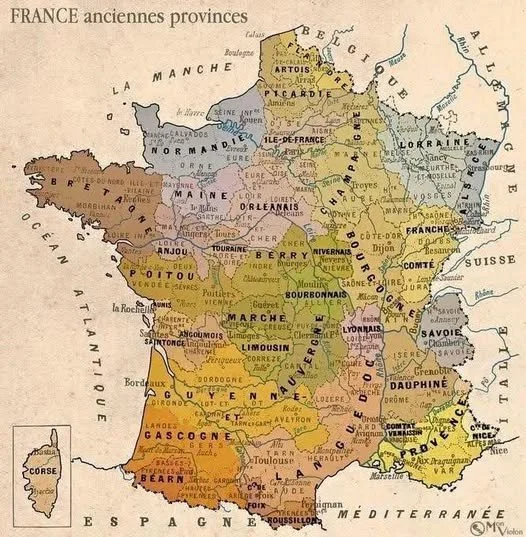

Marie Riton was born about 1623 in Le Bourg-sous-la-Roche, near La Roche-sur-Yon in the former province of Poitou, to Robert Riton and Marguerite Guyon. The absence of a surviving baptismal record leaves uncertainty regarding her early religious formation. Her place of origin, however, situates her in a region deeply affected by the Catholic–Protestant divide of 17th-century France.

By the early 1640s, Marie had relocated to the La Rochelle area, a major Atlantic port and long-standing Protestant stronghold. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Protestants certain rights, but by the 1620s and 1630s, those protections were eroding. La Rochelle itself had endured a devastating siege in 1627-28, and the Protestant community lived under increasing pressure.

What drew a young woman from Poitou to this contested port city? The records do not say. But it was here that Marie's documented life begins—with scandal, conversion, and eventually, escape.

Illegitimacy and Precarity

On 6 November 1644, Marie baptized a daughter named Marie in the parish church of Sainte-Étienne in Ars-en-Ré, on the Île de Ré. The child's father, Abraham Brunet, was identified in the register as belonging to the religion prétendue réformée—the "so-called reformed religion," the official Catholic term for Protestantism.

Because the parents were unmarried, the child was designated naturelle—illegitimate. In 17th-century France, illegitimacy carried enduring social consequences for women, often limiting marriage prospects and economic security. The child disappears from the record and almost certainly died in infancy, either in France or during the Atlantic crossing.

A Public Profession of Protestant Faith

Seven months later, on 29 June 1645, Marie appeared before the Reformed Church in La Rochelle and formally professed her Protestant faith. The record states that she "abjured the errors of the Roman Church" and declared her intention to live and die in the Reformed religion.

"Marie Ritoz natifue du bourg de la Roche sur lion en poiton a faict abjuration des Erreus de l'Eglise Romaine et protesté de vouloir vivre et mourir en la profession de la verité enseignée en nostre Eglise..."

— La Rochelle Reformed Church Register, June 29, 1645This declaration may represent either a reaffirmation of an existing Protestant identity, or a formal conversion, possibly influenced by her association with Abraham Brunet or by La Rochelle's Protestant environment. In either case, the profession placed Marie firmly within the Huguenot community at a moment when legal and social pressure on Protestants was intensifying.

Emigration as a Fille à Marier

Between 1645 and 1650, Marie left France for New France, almost certainly departing from La Rochelle. She belongs to the early cohort of Filles à marier, women recruited by private sponsors or religious networks before the establishment of the crown-funded Filles du roi program in 1663.

Unlike later royal wards, the Filles à marier:

Marie's motivations likely included escape from social stigma following an illegitimate birth, limited economic prospects in France, the loss of her child, and deteriorating conditions for Protestants. Because New France was officially Catholic, Marie would have needed to convert—either sincerely or nominally—before or shortly after her arrival, or else conceal her Protestant background entirely.

No Canadian record references her Reformed faith. The woman who had publicly professed Protestantism in 1645 would, by 1660, be confirmed into the Catholic Church by Bishop Laval himself.

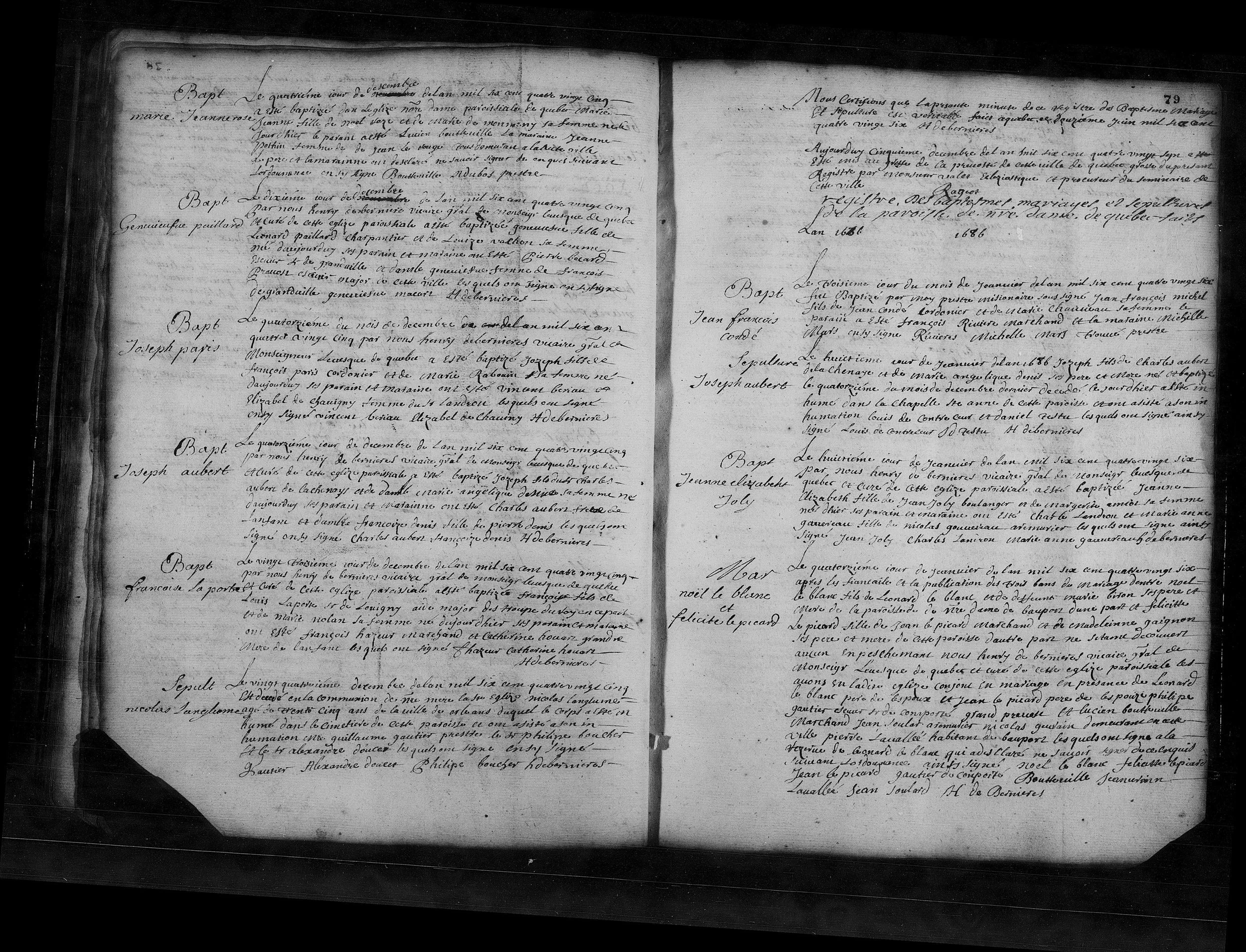

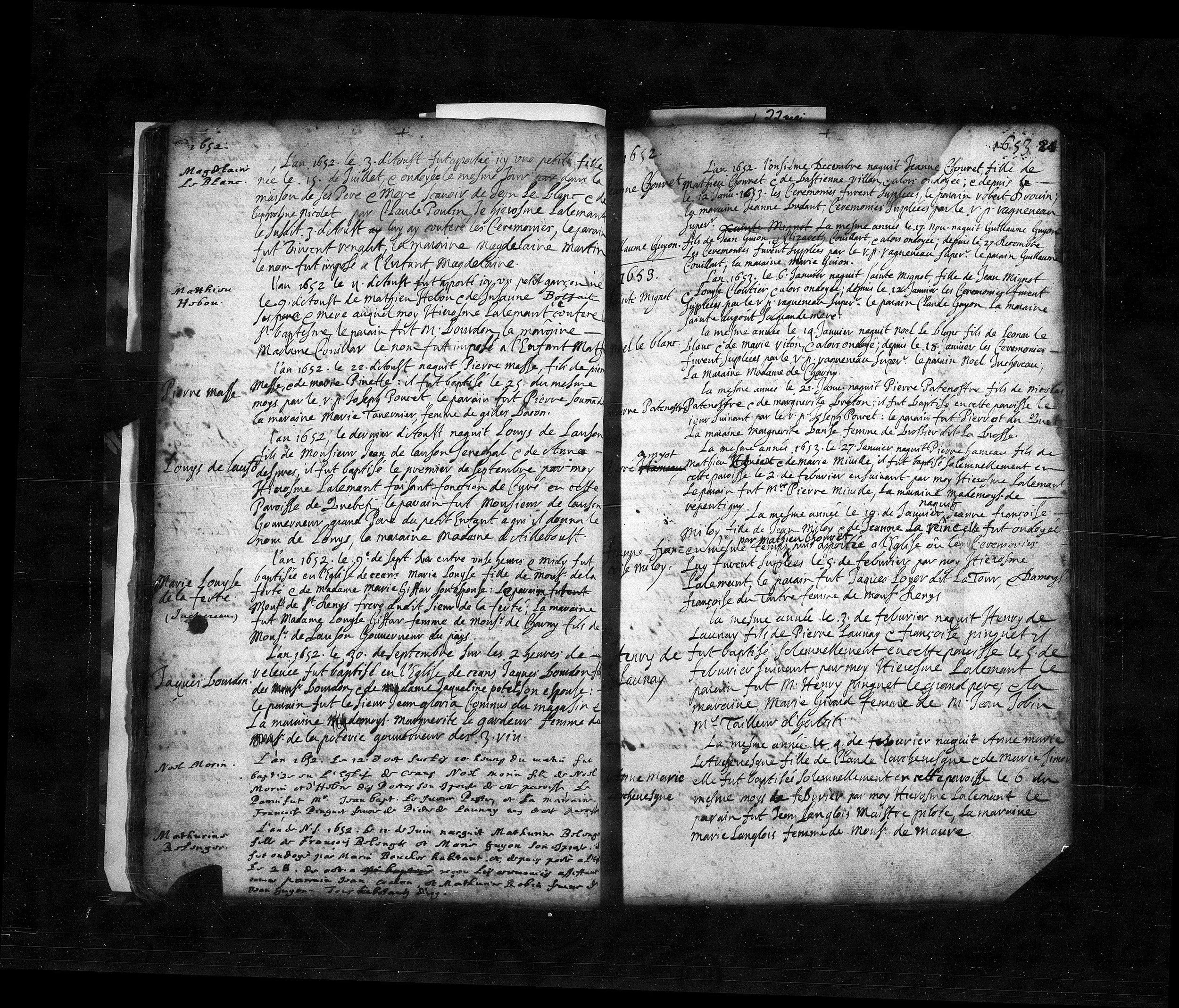

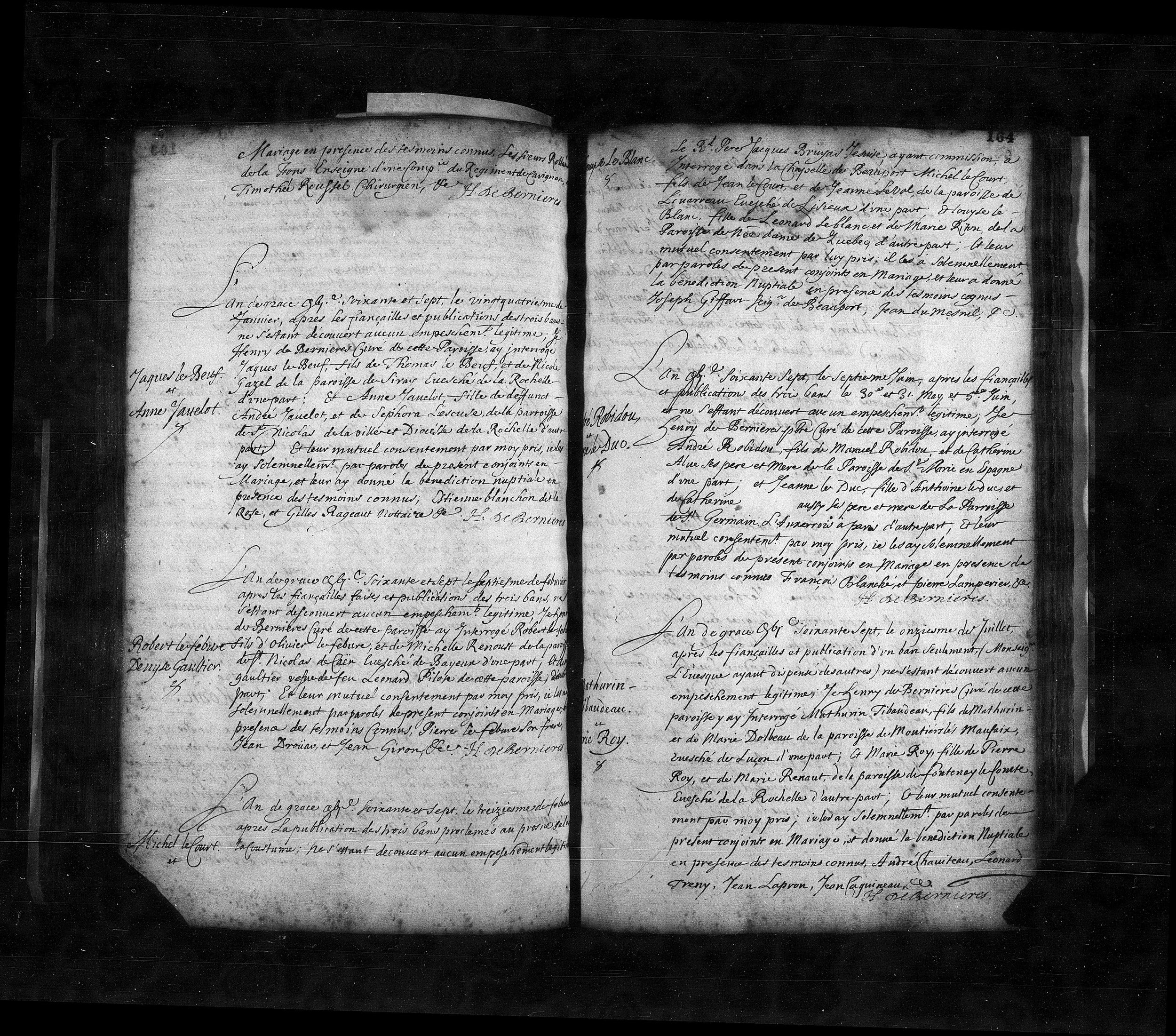

August 23, 1650: Marriage at Beauport

On August 23, 1650, Marie married Léonard Leblanc at the residence of Robert Giffard, seigneur of Beauport. The marriage record at Notre-Dame de Québec identifies Marie as being from "Bourg sur la Roche en Poitou" and Léonard as a mason from Blessac in the pays de la Marche.

Léonard Leblanc, born about 1626 in Blessac (arrondissement of Aubusson, diocese of Limoges), was the son of Léonard Leblanc and Jeanne Fayande. A master mason by trade, he had likely arrived in New France around 1647, working a standard three-year contract before establishing himself as an independent craftsman.

The marriage took place at the home of Robert Giffard, the seigneur who had been recruiting settlers for Beauport since 1634. Giffard's presence suggests that Marie and Léonard were already connected to the Beauport community—perhaps Léonard had done masonry work for the seigneur, or Marie had arrived under arrangements connected to the seigneurial household.

Through this marriage, Marie entered the network of habitant families that formed the backbone of early Beauport. The stigma of her French past—the illegitimate child, the Protestant conversion—would remain buried across the Atlantic. In New France, she was simply Marie Riton, wife of the mason Léonard Leblanc.

Family Life: 1651-1662

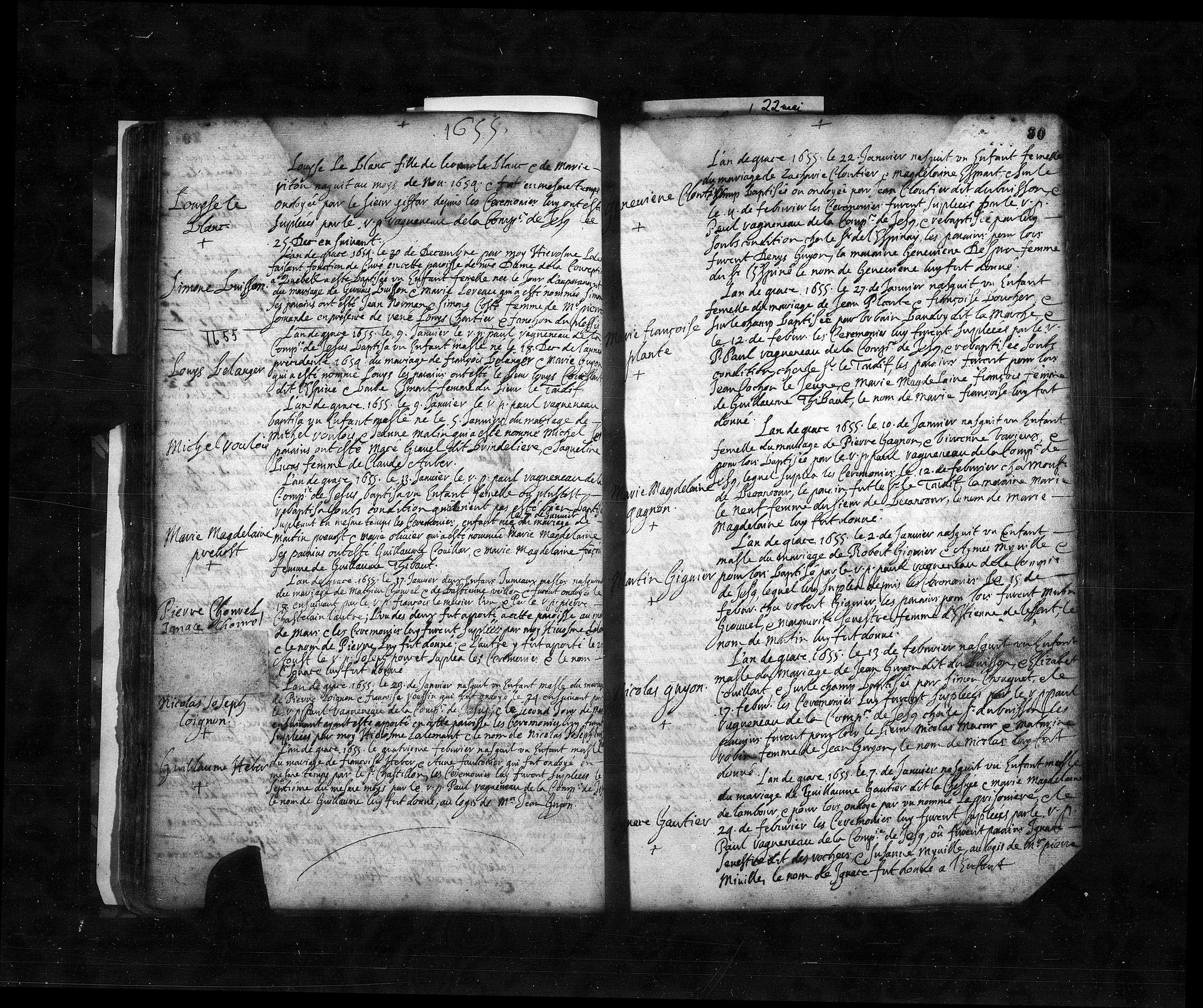

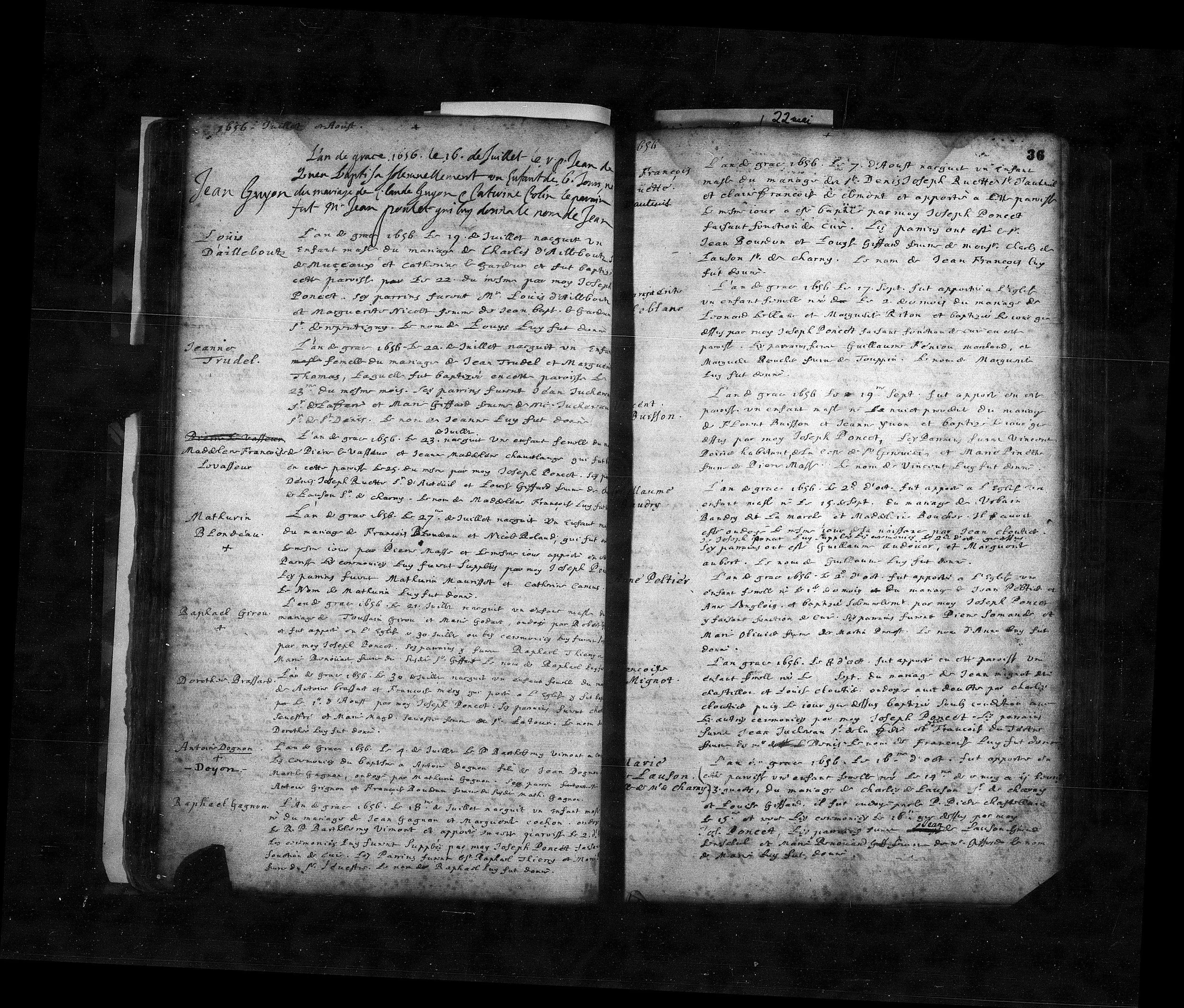

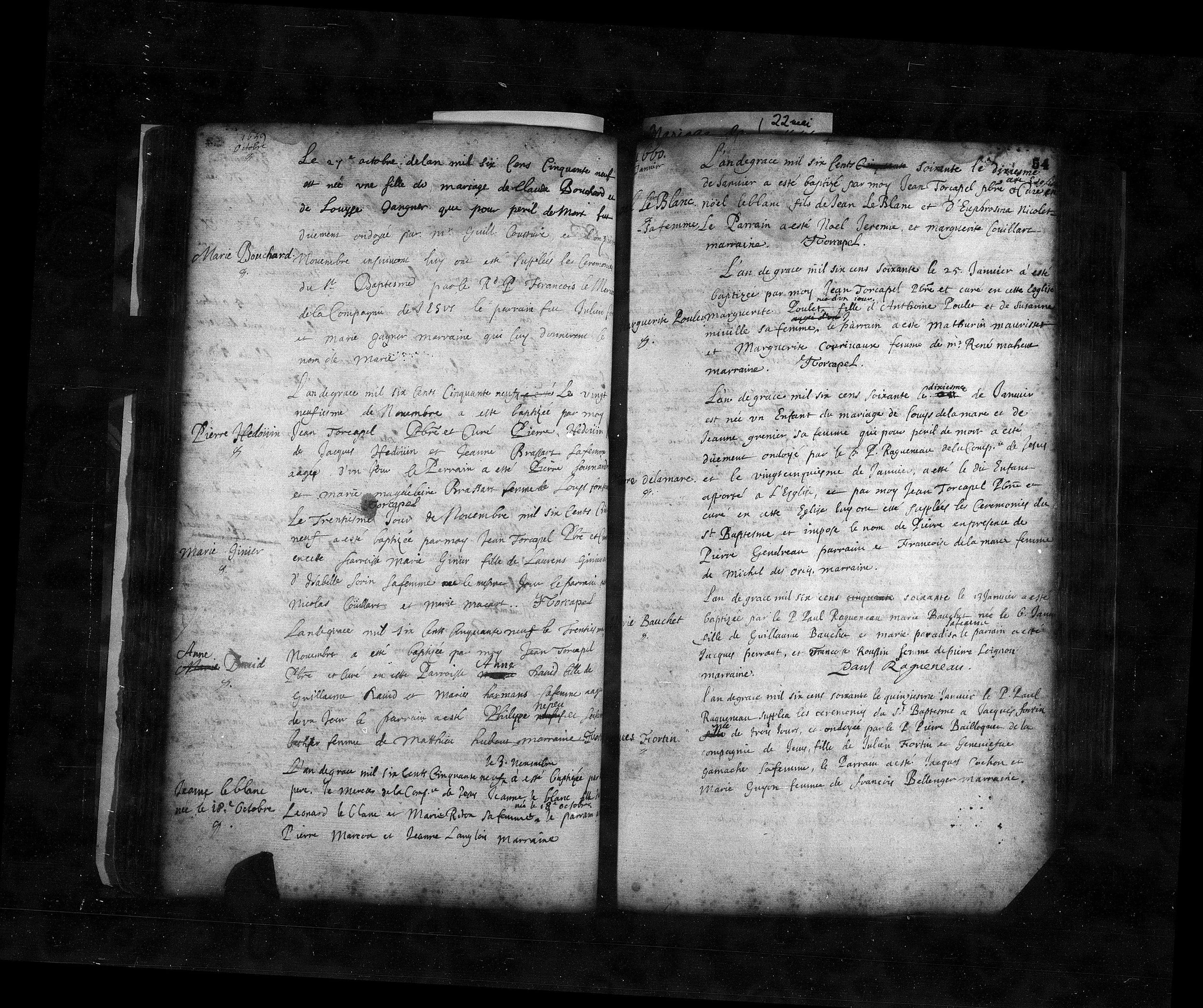

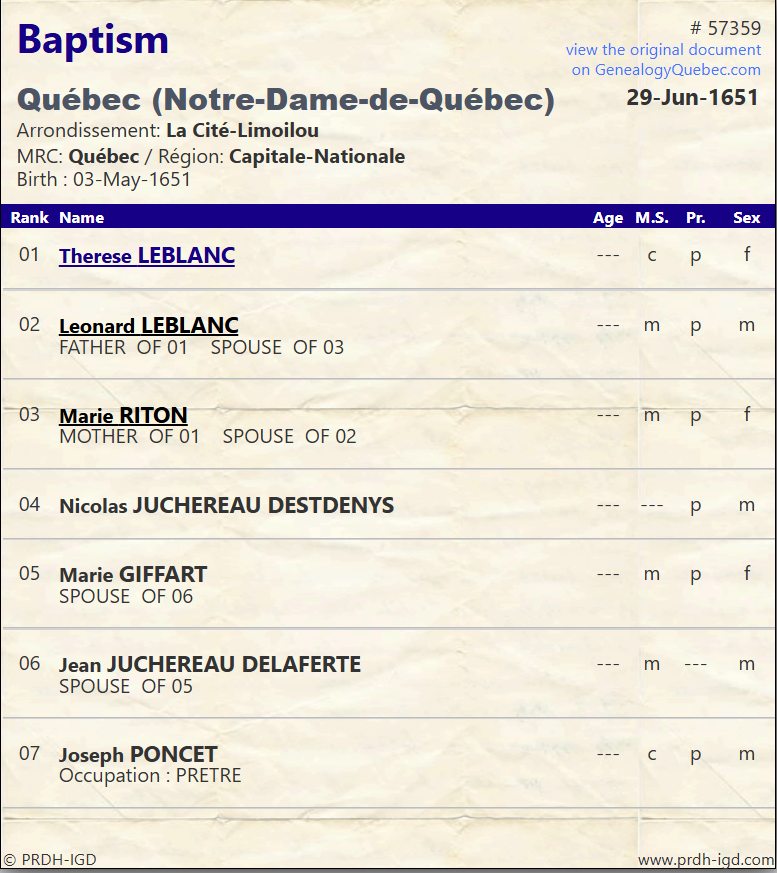

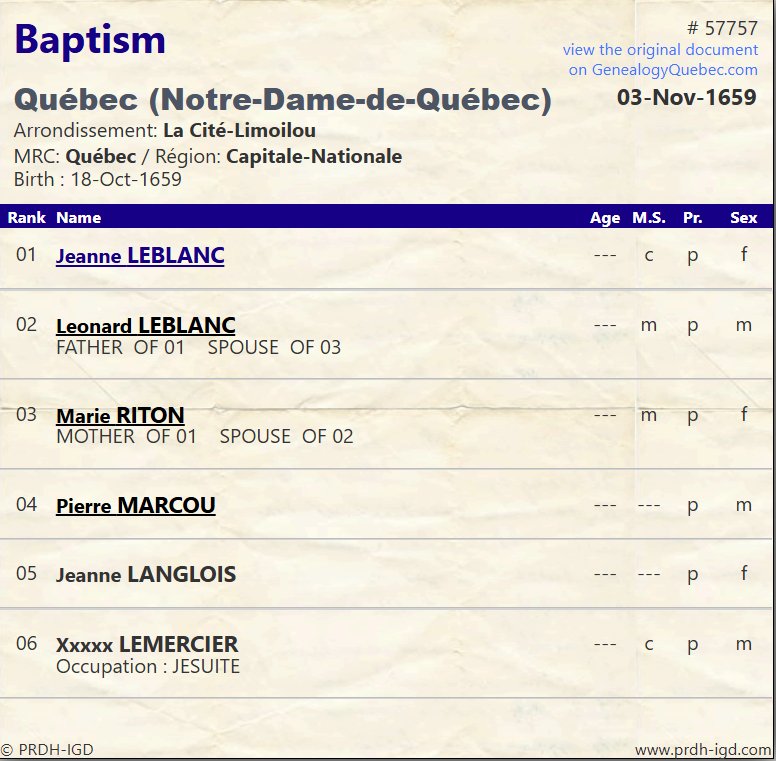

Between 1651 and 1662, Marie gave birth to seven children—one son and six daughters. All seven survived infancy, a remarkable achievement in an era when child mortality claimed perhaps one in four before age five. The baptism records from Notre-Dame de Québec document each birth:

| Child | Birth | Baptism | Marriage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marie Thérèse | May 3, 1651 | June 29, 1651 | 1665 Pierre Lavallée; 1686 Toussaint Giroux |

| Noël | Jan 14, 1653 | Jan 18, 1653 | 1686 Félicité Le Picard |

| Louise | Nov 1654 | Dec 25, 1654 | 1667 Michel Le Court; 1686 Guillaume Boissel |

| Marguerite | Sept 2, 1656 | Sept 17, 1656 | 1670 Pierre Bazin |

| Marie (Élisabeth) | Jan 15, 1658 | July 8, 1658 | 1672 René Cloutier |

| Jeanne | Oct 18, 1659 | Nov 3, 1659 | 1675 Pierre Morel; 1704-1706 Jean Baptiste Baudy dit Laverdure |

| Françoise | Jan 18, 1662 | Jan 19, 1662 | 1678 Jean Prévost/Provost; 1709 Pierre Delorme dit Sanscrainte |

The family settled at the Bourg de Fargy in Beauport, where Léonard practiced his masonry trade while also working the land. The censuses of 1666 and 1667 capture the household at its peak: Léonard age 40, Marie age 40-43, and five of their seven children still at home.

Religious Conformity in New France

On 24 February 1660, Marie was formally confirmed into the Catholic Church at Notre-Dame de Québec by François de Montmorency-Laval, alongside sixty-five others. She was recorded as originating from the bishopric of Luçon—consistent with her Poitou origins.

No record of a formal abjuration survives in the Canadian archives, but confirmation indicates full acceptance into Catholic sacramental life. Her religious trajectory—from possible Catholic origins, to Protestant profession in 1645, to Catholic conformity by 1660—reflects the adaptive strategies required of immigrant women in New France.

The 1660 confirmation by Bishop Laval may have been required specifically because of Marie's earlier Protestant affiliation—or it may simply have been part of the bishop's efforts to strengthen Catholic practice in the colony. Either way, it marked Marie's complete integration into the religious life of New France.

For the woman who had once publicly "abjured the errors of the Roman Church," this was a profound reversal. Whether it represented genuine conversion or pragmatic survival, only Marie knew. What the records show is that she raised her seven children as Catholics, saw them married in the Church, and died having received the last rites.

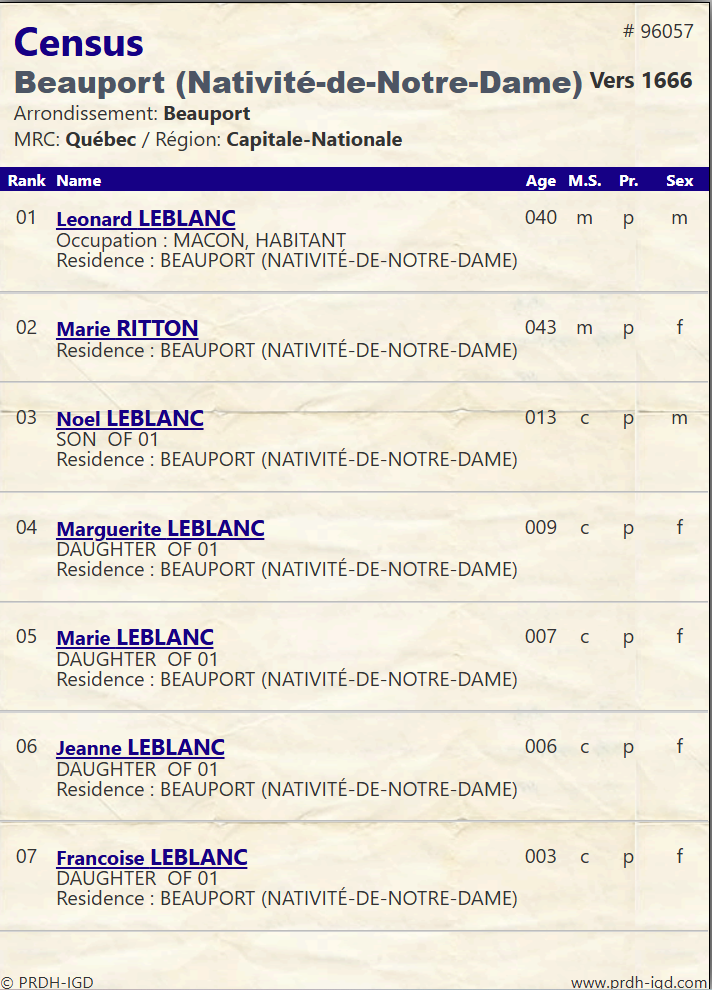

The 1666 and 1667 Censuses

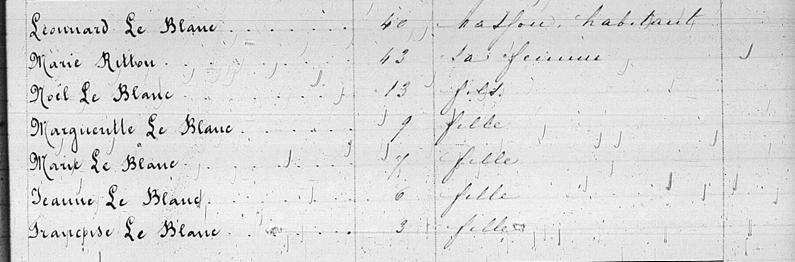

The first comprehensive censuses of New France, taken in 1666 and 1667, provide rare snapshots of the Leblanc household. These documents record not just names and ages, but occupations, livestock, and cultivated land—the material foundations of colonial life.

1666 Census - Beauport

- Léonard Le Blanc, 40, maçon habitant

- Marie Ritton, 43, sa femme

- Noël, 13, fils

- Marguerite, 9, fille

- Marie, 7, fille

- Jeanne, 6, fille

- Françoise, 3, fille

- 1 bête à cornes (cattle)

1667 Census - Beauport

- Léonard Le Blanc, 40

- Marie Riton, 40

- Noël, 14

- Marguerite, 11

- Marie, 10

- Jeanne, 7

- Françoise, 5

- 3 bêtes à cornes • 18 arpents en valeur

The discrepancy in Marie's age between the two censuses (43 in 1666, 40 in 1667) is typical of early colonial records where ages were often estimated. The 1667 census shows the family's prosperity growing: their cattle had tripled from one to three head, and they now had 18 arpents (about 15 acres) under cultivation.

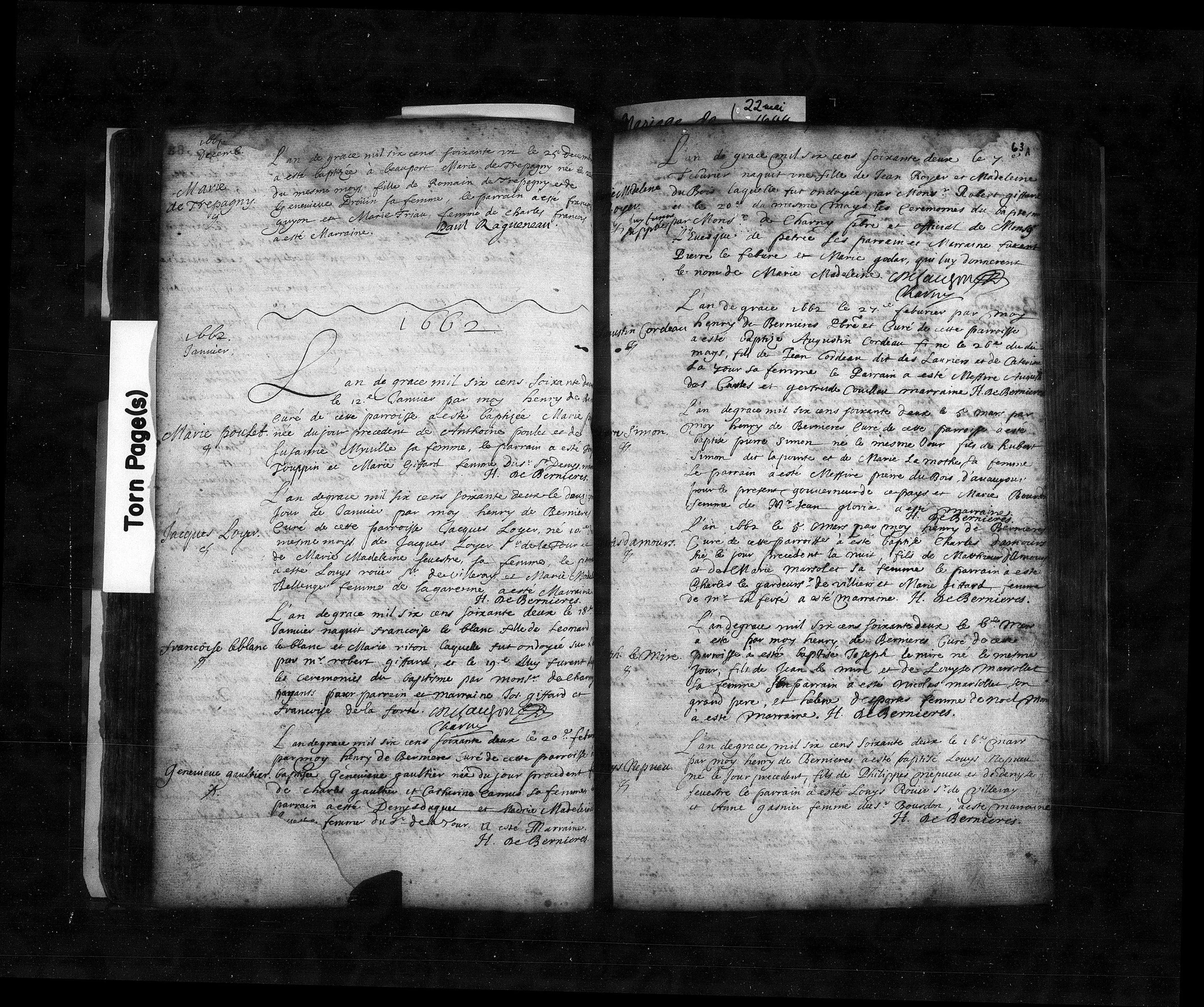

A Network of Marriages

Marie's six daughters and one son formed marriage alliances that extended the family's connections throughout the colony. The daughters married into settler families including the Lavallées, Le Courts, Bazins, Cloutiers, Morels, and Prévosts—names that still populate Quebec today.

Marie Thérèse: The Eldest Daughter

On January 12, 1665, Marie Thérèse became the first of the Leblanc children to marry, wedding Pierre Lavallée of the parish of St-Jean in the archbishopric of Rouen. The marriage record at Notre-Dame de Québec notes her residence as Beauport—the family's home for fifteen years.

Louise: 1667

Louise married Michel Le Court on February 13, 1667. The marriage record provides the fullest documentation of Marie Riton's name in a child's marriage, listing both parents: "Léonard Leblanc" and "Marie Riton."

Marguerite: 1670

Marguerite married Pierre Bazin on July 19, 1670. Pierre was the son of Estienne Bazin and Marthe de Reinville—connecting the Leblanc family to another established Beauport lineage.

Noël: The Only Son

Marie did not live to see her son Noël marry. On January 14, 1686—twelve years after her death—Noël wed Félicité Le Picard at Notre-Dame de Québec. The marriage record poignantly notes Marie's status: "Marie Riton, mère de 01, décédée"—mother of the groom, deceased.

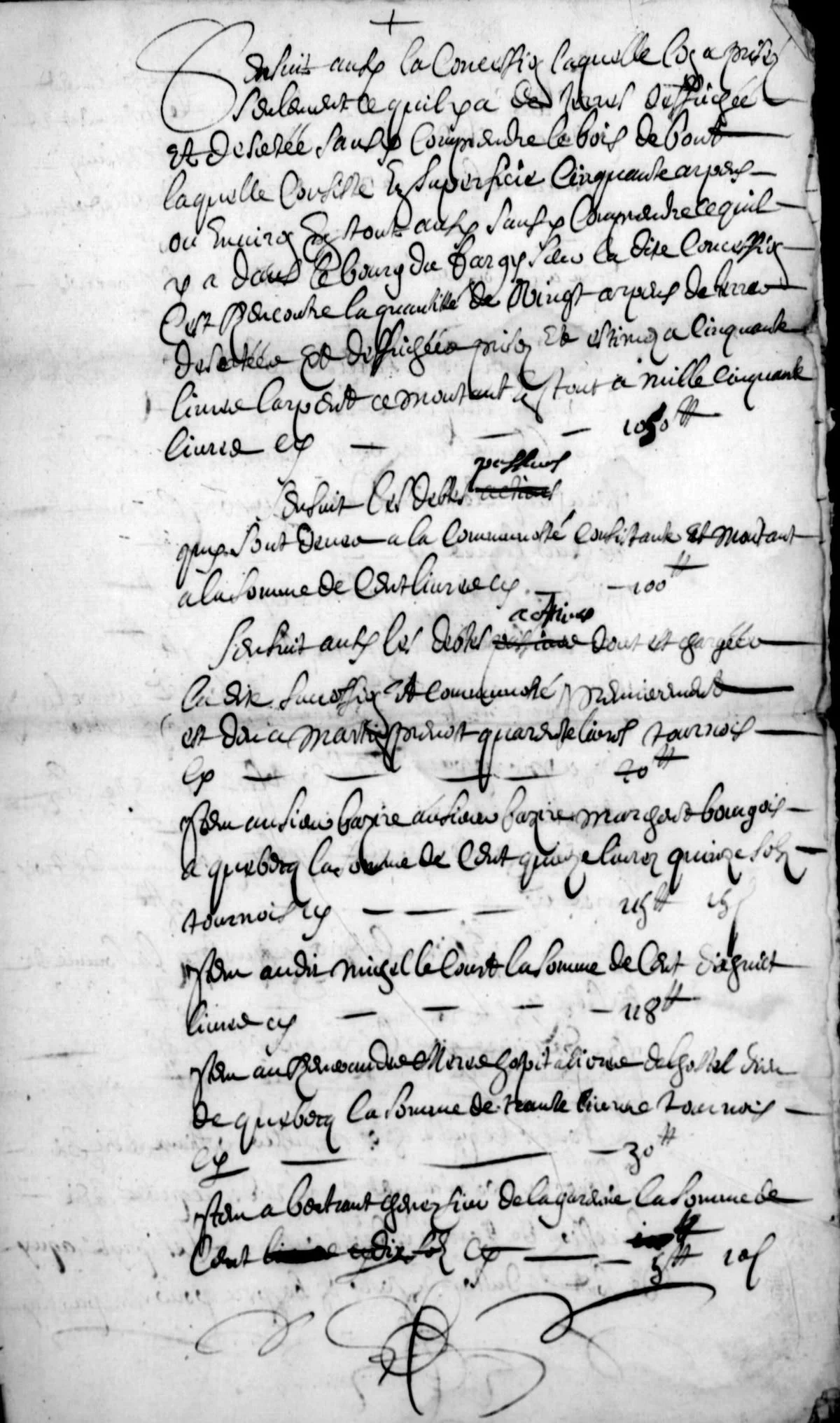

Death and Inventory: 1674

Marie Riton died at Beauport sometime between April 16 and November 4, 1674. On April 16, she dictated her will to notary Paul Vachon. On November 4, the same notary drew up a posthumous inventory of the marital estate.

The inventory reveals a household recovering from fire damage and burdened by debt, yet still possessing substantial land, livestock, and stored provisions. The document provides a rare material snapshot of a Fille à marier who survived long enough to become a landholding matriarch.

The inventory lists:

- A concession at the Bourg de Fargy in Beauport, including cultivated land and woodlot

- Twenty arpents of cleared and cultivated land

- Fifty arpents total including woodland

- Livestock, stored grain, and household goods

- Debts totaling over 500 livres to various creditors

Léonard survived Marie by seventeen years, continuing to work as a mason and eventually donating all his possessions to his son Noël in 1679, on condition that Noël care for him in his old age. He spent nearly the entire month of May 1691 in the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, returned home, and died on October 6, 1691, at approximately 65 years of age.

Historical Significance

Marie Riton's life illustrates the often-overlooked realities of early female immigration to New France. She was not a royal ward, not protected by the Crown, and not insulated from risk. Her survival depended on adaptability—religious, social, and economic.

The GFNA database documents her descendants: between 4,270,000 and 4,690,000 Quebecers carry her genetic legacy through 14 generations. Her mtDNA haplogroup (H5a1, H5a1-T16093C) has been documented through the French Heritage Project, allowing descendants to trace their maternal lineage back to this woman who crossed the Atlantic in search of a new life.

While her husband Léonard's masonry left traces in stone—perhaps in buildings at Beauport that still stand—Marie's legacy endures through people: daughters, descendants, and the quiet demographic success that made the colony viable. The woman who once professed Protestant faith in La Rochelle became, through her children and grandchildren, one of the founding mothers of French Canada.

Document Gallery

Sources and Further Reading

Marie Riton's story has been reconstructed from parish registers, notarial records, and colonial censuses preserved at the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec and accessible through FamilySearch. Key sources include:

- Peter J. Gagne, The Filles à Marier, 1634-1662 — The definitive biographical dictionary of early female immigrants to New France, including Marie Riton's entry.

- GFNA (Genealogy of French in North America) — Denis Beauregard's database documenting the Leblanc-Riton family and mtDNA signatures.

- PRDH (Programme de recherche en démographie historique) — The comprehensive database of Quebec vital records.

- Notre-Dame de Québec Parish Registers, 1621-1679 — Original baptism, marriage, and burial records from FamilySearch.

- Census of Canada, 1666 and 1667 — Archives des Colonies, Série G1, preserving the earliest household enumerations.

- Paul Vachon Notarial Records, 1674 — Including Marie's will and the posthumous inventory.

Research Note: This profile documents Marie Riton as part of the Souliere Line's Founding Mothers collection. The methodology combines traditional genealogical research with DNA analysis and FamilySearch Full Text Search capabilities to recover stories that might otherwise remain hidden in the archives.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY