The Abitakijikokwe Discovery

How systematic parish searches, tribal identifiers, and FamilySearch Full Text Search revealed one of the most thoroughly documented Indigenous women in Quebec records.

Research Strategy & Documentation Process

Initial Research Phase

Starting Point

Subject: Gabriel Guilbault, d. 1833, St-Benoit, Quebec

Initial Problem: First wife listed only as "unknown Indigenous woman" or "Sauvagesse"

Available Data: Gabriel's death record, second marriage to Josette Closier (1815)

Reverse Chronological Search

- Located Gabriel's death record (April 8, 1833) — confirmed age 70

- Found 1815 marriage identifying him as "widower of Josette Sauvagesse"

- Calculated first wife's death between 1813-1814

- Identified Gabriel's birthplace: L'Assomption (1762)

The Breakthrough

The 1798 baptism of three children at St-Paul-de-Joliette identified the mother as "Josephte Sauvagesse, Sauteuse"—with the tribal specification "Sauteuse" meaning Ojibwe/Saulteaux woman. This tribal identification was the key that unlocked everything.

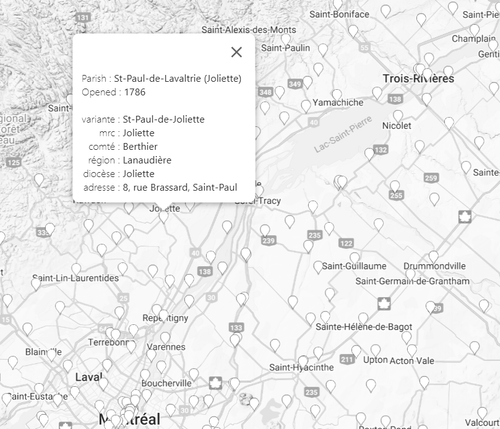

Geographic Clustering Strategy

Parishes searched along the Quebec-Ontario border, following fur trade routes and known Métis communities

1795-1805: St-Paul-de-Joliette

(baptisms found)

1799-1803: L'Annonciation, Oka

(marriage found)

1810-1820: Ste-Madeleine-de-Rigaud

(death references)

1830-1835: St-Benoit

(Gabriel's death)

Breakthrough Discovery Phase

The 1798 Mass Baptism

Search Parameters: St-Paul-de-Joliette, 1795-1800, surname variations

Finding: October 10, 1798 — three children baptized together at St-Paul-de-Joliette

Critical Details Extracted

Mother: "Josephte Sauvagesse, Sauteuse"

Children's ages: Indicated births from 1790-1797

Tribal identification: Sauteuse = Ojibwe/Saulteaux woman

This tribal specification was the key that unlocked everything.

Pattern Recognition Applied

Identified search terms:

- "Sauvagesse" (generic Indigenous woman)

- "Sauteuse/Sauteux" (specific Ojibwe)

- "de nation" (tribal member)

- Spelling variants: Guilbault/Guilbeau/Guilbeault

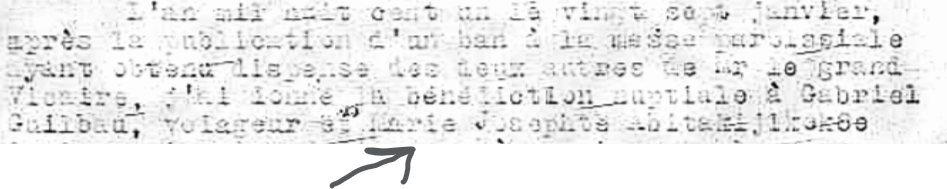

The Marriage Record Discovery

January 27, 1801 — L'Annonciation, Oka

Full Indigenous Name Preserved

Bride: "M. Josephte Abitakijkok8e"

Children legitimized: Four children recognized

Witnesses: Included individuals with Indigenous names

Significance: The suffix "-ikwe" confirmed authentic Ojibwe name, meaning "woman" in the Ojibwe language. This document preserves her full Indigenous name and shows the Catholic Church's recognition of their pre-existing relationship "à la façon du pays."

Technology Note: FamilySearch Full Text Search

Critical to this discovery was the Full Text Search capability on FamilySearch, which allows searching within the actual handwritten content of documents rather than just indexed fields. This tool enabled the discovery of records that weren't indexed under the Guilbault name variations but contained references to "Sauvagesse" and "Sauteuse" within the document text. This represented a breakthrough in genealogical research methodology.

Primary Source Documents

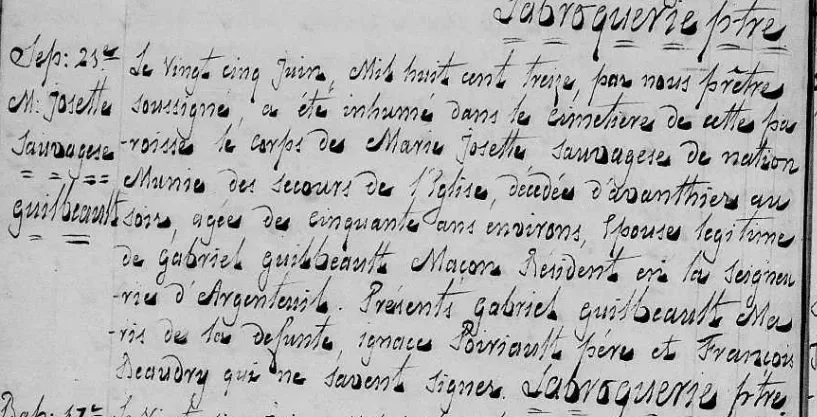

The original records that documented Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe across 103 years

10 Oct 1798 — Gabriel Jr. Gabriel Jr.'s baptism identifying mother as "Josephte Sauvagesse, Sauteuse" — the first tribal identification.

10 Oct 1798 — Angelique. Same-day baptism of Angelique and Joseph Claude, October 10, 1798.

10 Oct 1798 — Joseph Claude. Same-day baptism with godparents named, October 10, 1798.

27 Jan 1801 — Marriage Record. The breakthrough document — Marriage record preserving "Abitakijkok8e"

1801 Marriage Record (detail). Close-up showing the Ojibwe name "Abitakijkok8e" written by the priest.

1801 Marriage Record (detail/close-up). Detail showing the Ojibwe name "Abitakijkok8e" written by the priest.

1815 Second Marriage. Gabriel's 1815 remarriage identifying him as "widower of Josette Sauvagesse"

1893 Notarial Document. Legal document still referencing "Marie Josette Sauvagesse de nation" 80 years after her death.

Verification Phase

Cross-Reference Validation

Each child traced forward to establish complete family documentation:

Children Documented

Gabriel Jr. (b. June 1790): FamilySearch Film #100437666, Image 683 — Mother identified as "Sauteuse" (Ojibwe/Saulteaux). Traced to adulthood with confirmed parentage.

Angelique (b. ~1792): FamilySearch Film #100437666, Image 682 — Age at baptism: 6 years. Death: April 15, 1819.

Joseph Claude (b. June 1797): Same baptism record as siblings — Age at baptism: 16 months. Traced to adulthood.

François (b. Sept 10, 1799): FamilySearch Film #100437666, Image 707 — Died: April 3, 1801. Complete birth-death cycle documented.

Marie Louise (b. Jan 24, 1802): Oka Parish Records — Mother listed as "Marie Josephte Tabitakijokoke". Died: May 27, 1803.

Louis (b. 1806): Baptismal record in parish registers — No death record found. Likely survived to adulthood.

Name Analysis

"Abitakijkokwe" Deconstruction

- Recognized Algonquian language structure

- The suffix "-ikwe" means "woman" in Ojibwe

- Consistent with Ojibwe naming patterns

- Various spellings in records (Abitakijikokwe, Abitakijkok8e, Tabitakijokoke) reflect French attempts to phonetically record an Ojibwe name

Historical Context

Fur Trade Society

Marie Josephte's union with Gabriel Guilbault represents a typical fur trade marriage pattern:

- Initial Union (c.1789-1790): Relationship began "à la façon du pays" (according to the custom of the country)

- Children Born (1790-1799): Four children born before Catholic marriage

- Church Marriage (1801): Formalization of existing relationship

- Legitimization: Children recognized and legitimized by the Church

Métis Identity Formation

This family represents classic Métis ethnogenesis: French-Canadian voyageur father, Ojibwe/Saulteaux mother, children raised between two cultures, and continued recognition of Indigenous heritage in subsequent generations.

Geographic Context

The Oka/Deux-Montagnes region was home to established Indigenous communities. The location along the Ottawa River was traditional Ojibwe/Algonquin territory and a major fur trade route, connecting Gabriel's work as voyageur with Indigenous trading networks.

Research Tools & Techniques

FamilySearch

- Quebec Catholic Parish Records

- Film #100437666 (St-Paul-de-Joliette baptisms)

- Film #008130869 (L'Annonciation marriage record)

- Full Text Search Feature (critical breakthrough)

Ancestry.com

- Drouin Collection

- Quebec Vital Records

Archives Nationales du Quebec

- Notarial records

- Parish duplicates

Language Considerations

- French paleography skills required

- Understanding of Latin sacramental formulas

- Recognition of Ojibwe linguistic patterns

- Historical French-Canadian spelling variations

Critical Success Factors

What Made This Case Solvable

- Priests who recorded rather than erased Indigenous identity — Unlike many colonial records that omitted Indigenous names entirely, the priests in these parishes chose to preserve Marie Josephte's Ojibwe name and tribal affiliation

- Mass baptism creating clustered records — The October 10, 1798 baptism of three children together provided concentrated information and established the family unit

- Preservation of Indigenous name in marriage record — Despite an 11-year gap between the relationship's start (~1789-1790) and the 1801 Catholic marriage, the priest recorded her full Ojibwe name

- Consistent geographic area — The family remained within the Quebec-Ontario border region, allowing systematic parish-by-parish searches

- Notarial records providing late confirmation — Legal documents maintained her Indigenous identity decades after death, providing verification points

Obstacles Overcome

- 15+ spelling variations of surnames (Guilbault/Guilbeau/Guilbeault)

- Missing direct death record for Marie Josephte

- Language barriers (French/Latin/Ojibwe)

- Geographic spread across multiple parishes

- Time gap between relationship start (1790) and marriage (1801)

Genealogical Proof Standard Analysis

Genealogical Proof Standard: MET

Documentation Strength: EXCEPTIONAL — Multiple primary sources spanning 1798-1893 with consistent identification as Indigenous woman across all records

Lessons Learned

Key Takeaways

- Indigenous ancestors can be documented in colonial records when priests chose to record rather than erase identity

- Persistence through spelling variations essential — both for surnames and Indigenous names

- Understanding historical context crucial — knowledge of fur trade customs and "à la façon du pays" marriages

- Multiple record types provide fuller picture

- Legal documents can preserve identity long-term

Reproducible Strategies

- Start with known fur trade communities (Oka, Deux-Montagnes, along Ottawa River)

- Search for cultural identifiers, not just names (Sauvagesse, Sauteuse, "de nation")

- Check witnesses/godparents for community networks

- Review all children's records, not just direct line

- Examine legal documents decades after death

- Use Full Text Search features when available

Final Assessment

This case represents exceptional documentation for an Indigenous ancestor in colonial records. The preservation of Marie Josephte Abitakijikokwe's Ojibwe name, consistent tribal identification, and legal recognition across nearly a century (1790-1893) makes this one of the most thoroughly documented Indigenous women in Quebec parish records.

Her descendants can claim with full documentary confidence their Métis heritage through this Ojibwe matriarch.

The methodology employed—combining systematic searching, pattern recognition, linguistic analysis, and historical context—can be applied to other challenging Indigenous ancestry cases, though results this comprehensive remain rare.

L'Annonciation Church at Oka today—This sacred place, at the confluence of Indigenous and French cultures, holds the marriage register where her Ojibwe name was preserved on January 27, 1801.

Searching for Indigenous Ancestors?

For a detailed guide on recognizing patterns like these, request our free resource: "Five Signs of Indigenous Ancestry in Quebec Parish Records"