Two Families, One Story : To Chicago

To Chicago

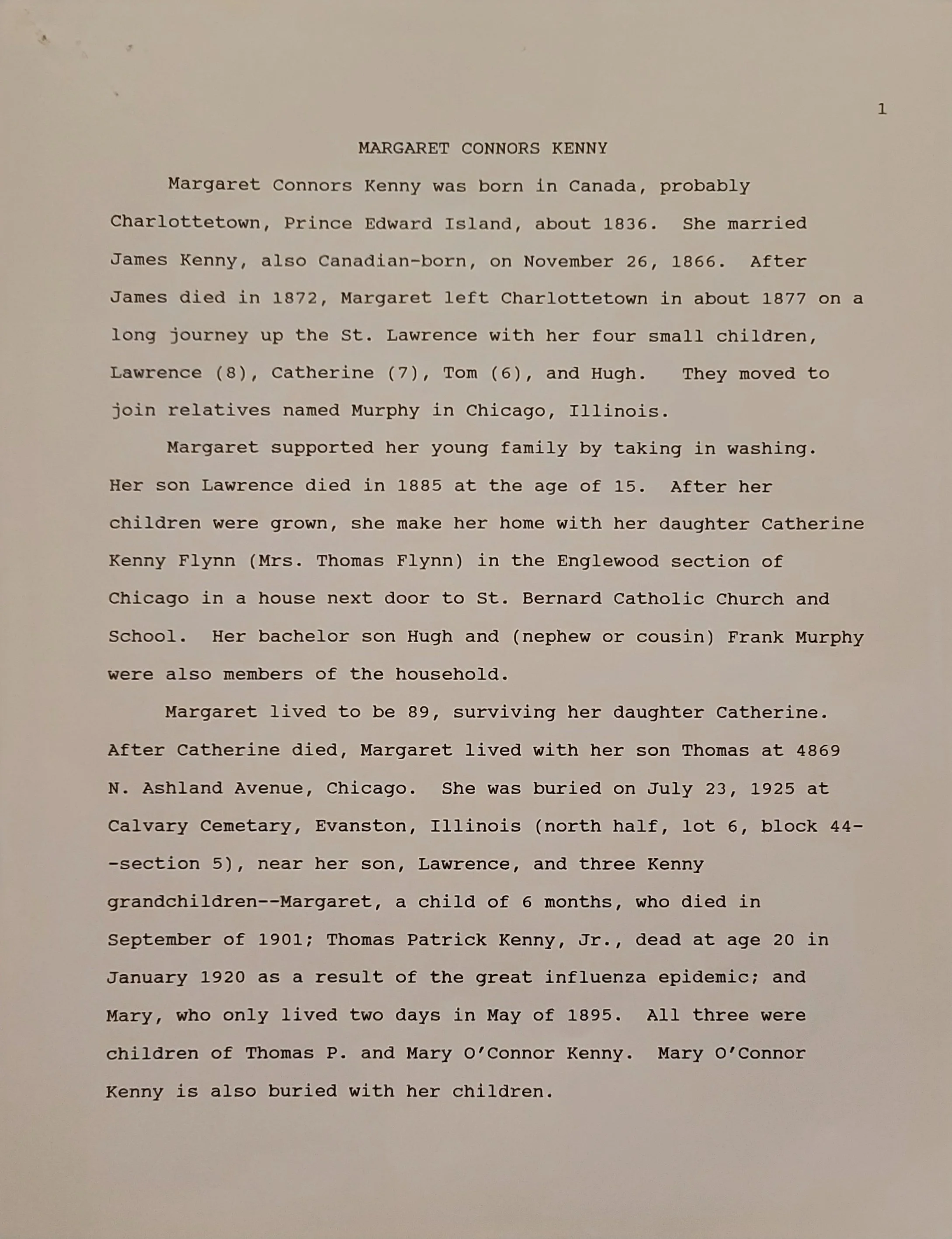

In the year James Kenny died—1872—Prince Edward Island was still five years from joining Canadian Confederation. Margaret Connors Kenny was thirty-six years old, widowed, with four children under the age of ten. For five years, she stayed. Then she left everything she knew and traveled a thousand miles to a city still rebuilding from fire.

This is the story of how a widow from Covehead became a Chicago pioneer.

The Decision

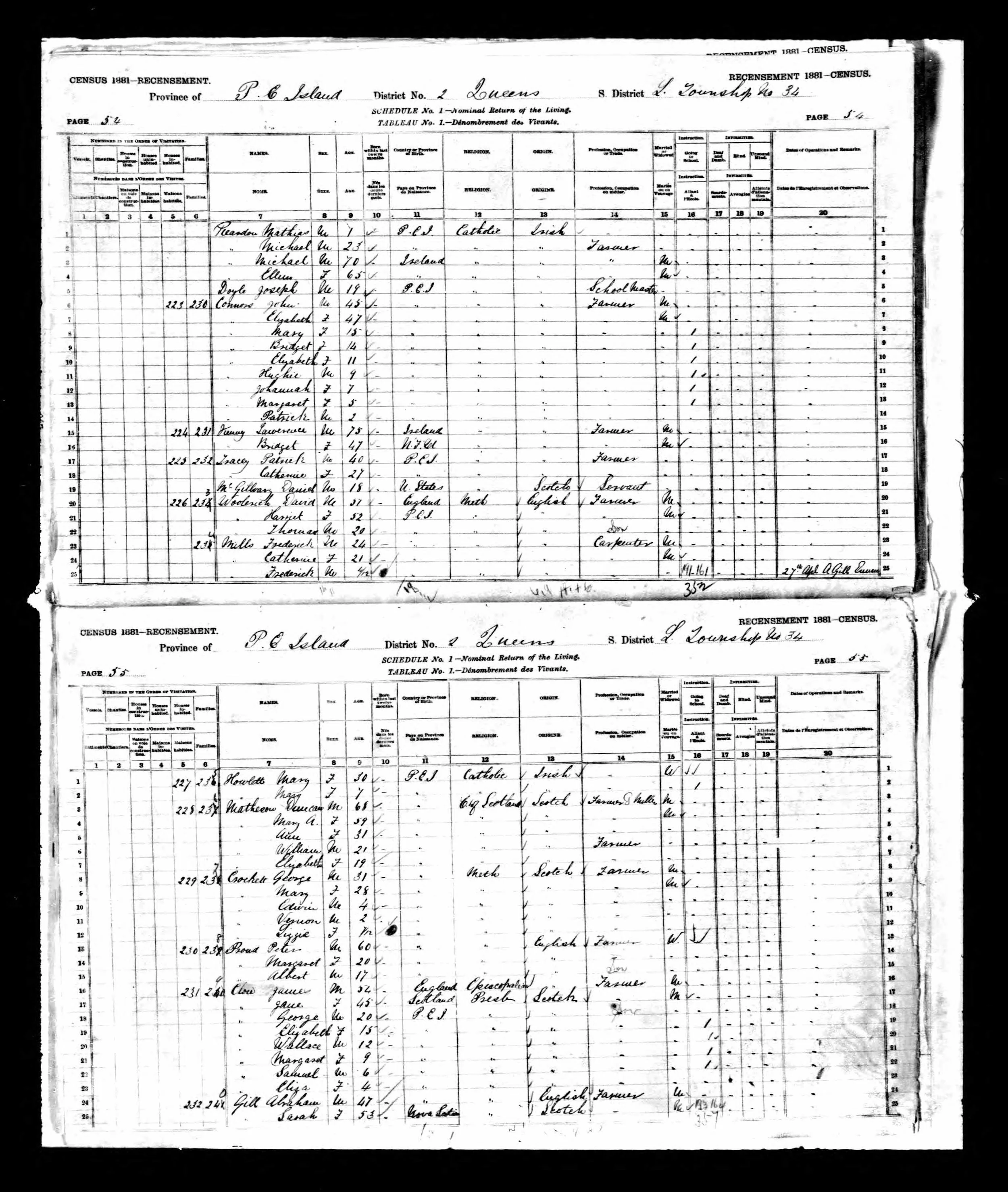

The 1881 census would later record Margaret's father-in-law Lawrence Kenny, then seventy-five years old, still farming at Covehead with his second wife Bridget Connors. Margaret's name does not appear beside them. By then, she was already gone.

The family narrative, preserved by her great-granddaughter Mary Ellen Molony Brady, places Margaret's departure around 1877:

"Margaret left Charlottetown in about 1877 on a long journey up the St. Lawrence with her four small children, Lawrence (8), Catherine (7), Tom (6), and Hugh. They moved to join relatives named Murphy in Chicago, Illinois."

What pushed her from the island she had known all her life? Prince Edward Island in the 1870s offered limited opportunity for a widow with young children. The leasehold system still constrained Island farmers—even those who owned their land struggled against thin soil and short growing seasons. The island's population had been bleeding westward for decades, young people seeking opportunity in Boston, in New York, in the booming cities of the American Midwest.

Chicago had been devastated by the Great Fire of 1871 but was rebuilding itself with furious energy. The Irish community was well established, concentrated in neighborhoods where Gaelic could still be heard in the streets, where the Catholic Church anchored social life, where a widow might find work and her children might find opportunity. Chain migration had created pathways—the Murphy relatives had gone before and could help Margaret find her footing.

A New Address

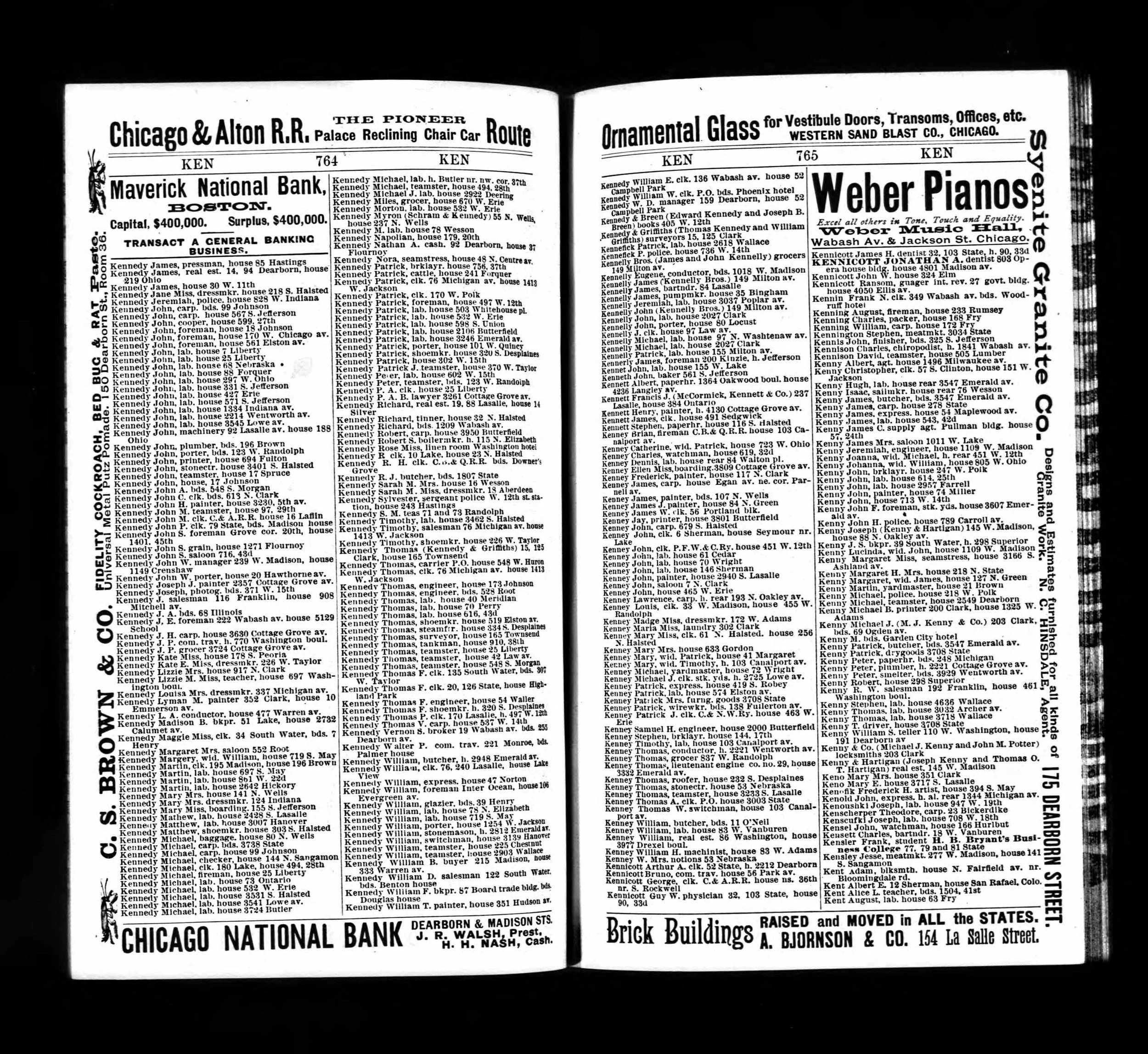

The first documentary evidence of Margaret in Chicago appears in the 1885 city directory:

Directory Record

"Kenny Margaret, widow James, house 127 N. Green"

— Lakeside Annual Directory of the City of Chicago, 1885

The address places her on the Near West Side, in a neighborhood dense with Irish and German immigrants, walking distance from factories and foundries, close to St. Stephen's Church where her children would be baptized and buried.

The family narrative records how Margaret supported her young family:

"Margaret supported her young family by taking in washing."

It was the most common occupation for immigrant widows—work that required no capital beyond a washboard and strong arms, work that could be done at home while watching children, work that left no records except in the aching shoulders of the women who performed it.

The First Loss

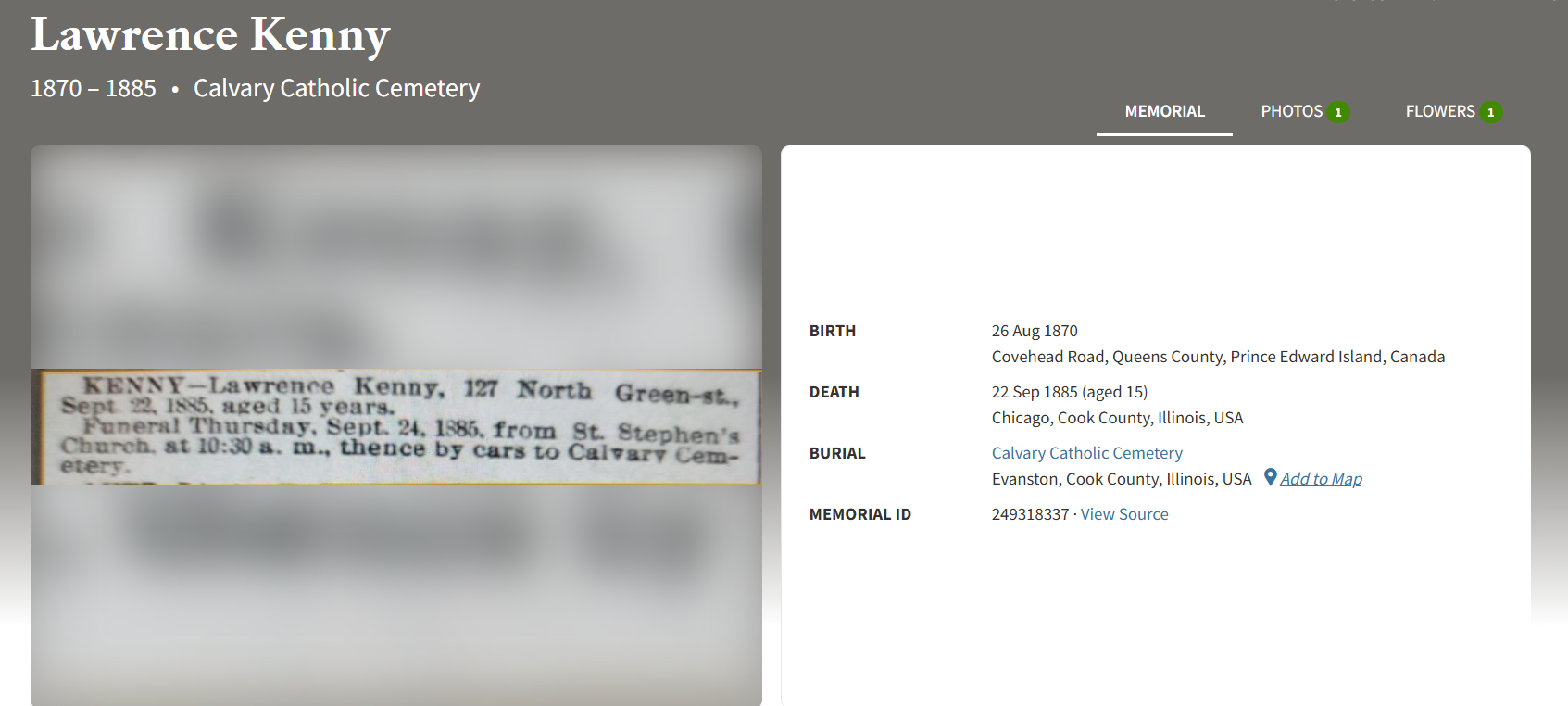

On September 22, 1885, Lawrence Kenny died at 127 North Green Street. He was fifteen years old.

Death Notice

"KENNY—Lawrence Kenny, 127 North Green-st., Sept. 22, 1885, aged 15 years. Funeral Thursday, Sept. 24, 1885, from St. Stephen's Church, at 10:30 a.m., thence by cars to Calvary Cemetery."

— Chicago Tribune, September 1885

He was buried at Calvary Catholic Cemetery in Evanston, the sprawling burial ground that served Chicago's Irish Catholic community. The cause of death is not recorded in the surviving notice. Whatever took him—disease, accident, the hazards of youth in an industrial city—it happened less than a decade after Margaret had brought her children to Chicago in search of a better life.

Lawrence had been born at Covehead Road, Prince Edward Island, on August 26, 1870. He had crossed an ocean's worth of distance with his mother and siblings. He had spent half his short life in one country and half in another. And now he lay in Illinois soil, the first of Margaret's children to be buried in their adopted homeland.

The Survivors

Three children remained: Catherine, Thomas, and Hugh. They would grow to adulthood in Chicago, marry, raise families, become Americans in ways their Island-born mother never entirely would.

Mother of nine children

Married Mary O'Connor and then Ellen O'Connor

Lived with family throughout life

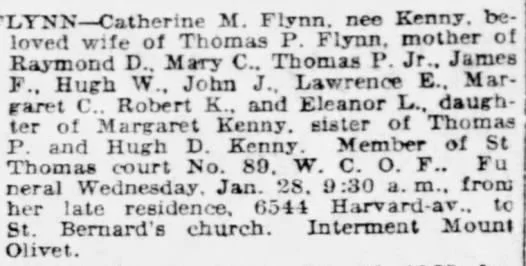

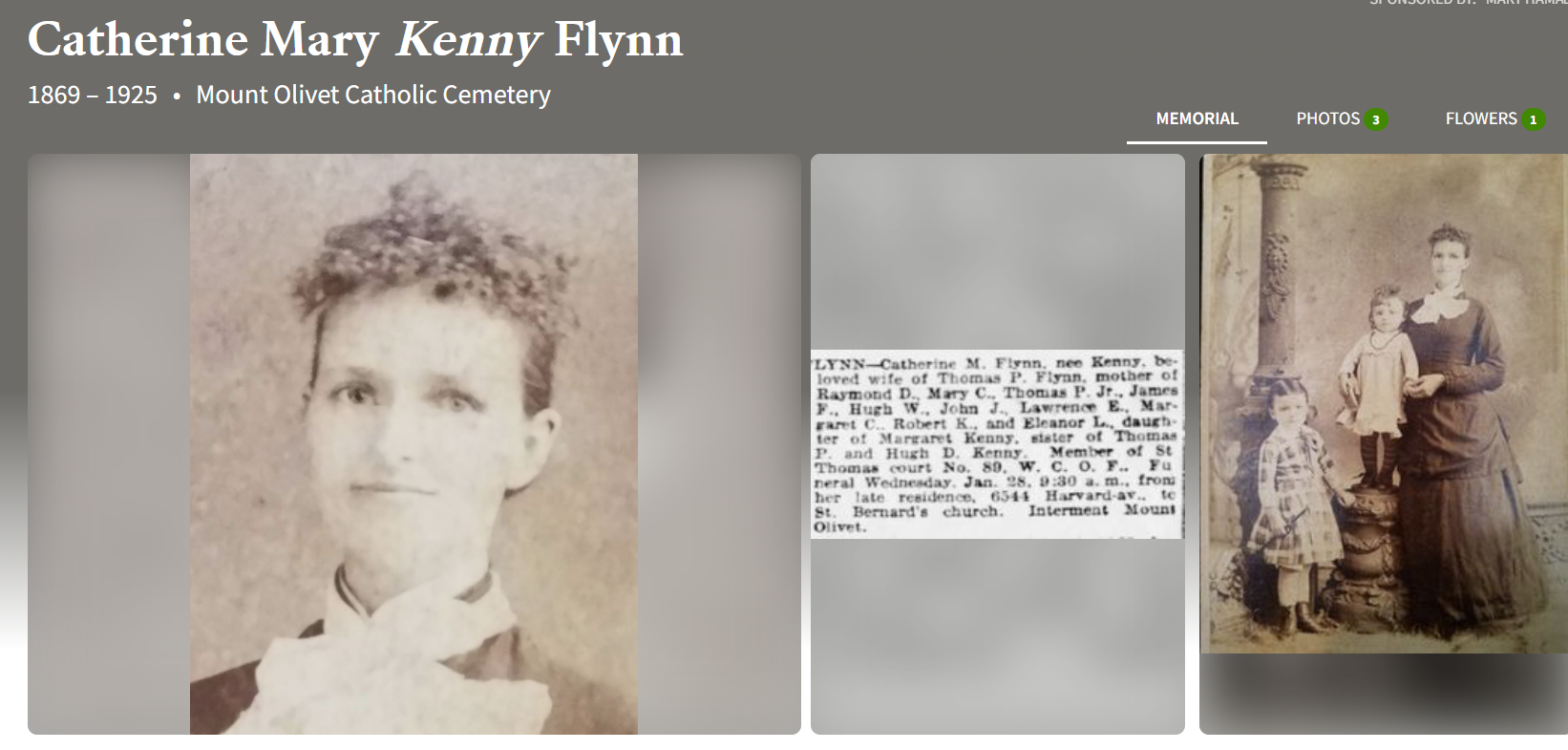

Catherine—called Kate or Katie—married Thomas P. Flynn. Her obituary, published in January 1925, would list nine children: Raymond D., Mary C., Thomas P. Jr., James F., Hugh W., John J., Lawrence E., Margaret C., Robert K., and Eleanor L. She had named a son Lawrence, keeping her lost brother's memory alive into the next generation.

Thomas P. Kenny would become a Battalion Fire Chief in Chicago, rising to a position of respect in a profession that Irish immigrants had made their own. The newspaper headline announcing Margaret's death in 1925 would identify her first as "Battalion Chief Kenny's Mother."

Hugh D. Kenny remained a bachelor, living with his mother and then with his married siblings throughout his life. The census records show him consistently present in the household—in 1900, 1910, and 1920—always listed with his sister Catherine's family.

The Long Years

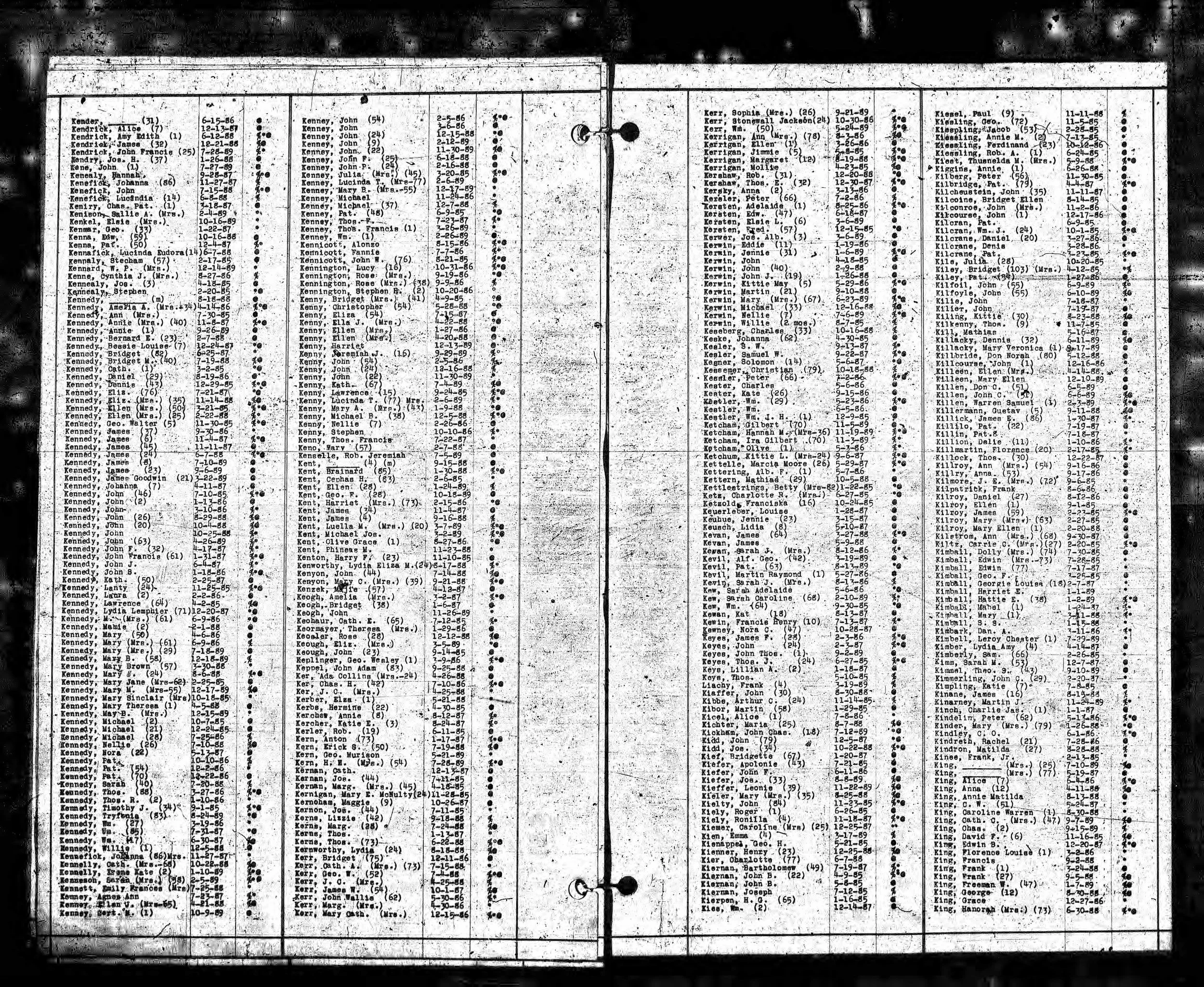

The census records trace Margaret's trajectory across four decades in Chicago:

Cook County, Illinois

Margaret, age 64, is living with her daughter Catherine Flynn and son-in-law Thomas P. Flynn. She is listed as "mother-in-law," having emigrated from Canada, her occupation blank. Her son Hugh, 33 and unmarried, lives with them too.

Cook County, Illinois

The household has moved to Englewood, into a house next door to St. Bernard Catholic Church and School. Margaret is now 74. The census shows an expanded household: Catherine and Thomas Flynn with their growing children, Hugh still present, and a "cousin" named Frank Murphy—likely the nephew mentioned in family accounts, connected to those Murphy relatives who had first drawn Margaret to Chicago.

Cook County, Illinois

Margaret is now 84, still living with Catherine's family. Her birthplace is recorded as Canada, her native tongue as English. She has lived in Chicago for more than four decades, has watched her grandchildren grow up American, has buried one child and would bury another—her daughter Catherine dying in January 1925, just months before Margaret herself.

The Island She Left Behind

Did Margaret ever return to Prince Edward Island? The records do not say. Her father-in-law Lawrence Kenny died on February 20, 1899, at Covehead—she would have been sixty-three, established in Chicago for more than two decades. If she traveled back for his funeral, no document survives to record the journey.

The distance from Chicago to Covehead in the 1890s would have been formidable: train to Boston or Montreal, steamer across the Gulf of St. Lawrence, then overland to the north shore of the Island. A journey of several days and considerable expense for a widow who had supported her family by taking in washing.

Perhaps she never saw Covehead again. Perhaps the red cliffs and the red soil and the farmhouse where she had married James Kenny existed only in memory, growing softer and less certain with each passing year, until even the memories belonged more to her children than to her—stories about a place they barely remembered, a life lived before America.

A Pioneer's Passing

Margaret Connors Kenny died on July 21, 1925, at the home of her son Thomas T. Kenny, 4869 North Ashland Boulevard. She was eighty-five years old—though the newspaper rounded up to eighty-nine—and had lived in Chicago for nearly fifty years.

Newspaper Notice

"Battalion Chief Kenny's Mother, a Pioneer, Dies"

Mrs. Margaret Kenny, 85 years old and for fifty years a Chicago resident, died yesterday at the home of her son, Battalion Fire Chief Thomas T. Kenny, 4869 North Ashland boulevard. She was born in Prince Edward Island, Canada. The funeral will be held tomorrow morning at Our Lady of Lourdes church, with burial in Calvary cemetery.

— Chicago Daily Tribune, July 22, 1925

She was laid to rest in the north half of Lot 6, Block 44, Section 5—near her son Lawrence, who had died forty years earlier at fifteen, and near three of her grandchildren:

Mary O'Connor Kenny, the wife of Margaret's son Thomas P. Kenny, is also buried with her children in that plot. The cemetery records show a family drawn together in death as they had been in life, Irish Catholic immigrants and their American-born descendants sharing the same Illinois earth.

Margaret Connors Kenny had crossed an ocean's worth of distance.

She spent forty-four years in Chicago, never returning to Covehead,

watching her children become Americans.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY