Two Families, One Story : Hugh Connors, Patriarch

Hugh Connors, Patriarch

On November 22, 1890, Hugh Connors died at his farm on Friston Road in Lot 34, Prince Edward Island. He was approximately ninety years old. The Summerside Journal recorded his passing in a brief notice that summarized a life spanning nearly a century: emigration from Ireland, decades of farming on the Island, and the raising of nine children who had married, scattered, and multiplied. Hugh Connors died a widower—Mary Henepy had predeceased him—but four sons, five daughters, and "a large circle of grandchildren to mourn their loss."

His death marked the end of an era for the Connors family on Prince Edward Island. Hugh had arrived in 1832, a young man from County Wexford who had first tried his luck in Newfoundland and New Brunswick before settling on Lot 34. Now, as his body was laid to rest, his daughter Margaret was already building a new life 1,500 miles away in Chicago. His grandson, David (Moses' son) would probably become the last Connors landholder in Covehead. And his unmarried daughter Ann—the spinster aunt—would need a home.

☘ The Obituary

Summerside Journal, December 4, 1890

The obituary notice for Hugh Connors as documented in "From Ireland to Prince Edward Island," compiled by the Prince Edward Island Genealogical Society from newspapers, obituary notices, and cemetery transcriptions.

The obituary's brevity belies the scope of Hugh's life. Ninety years. From the hills of County Wexford in the Ireland of King George IV to the farmland of Prince Edward Island in the Canada of Queen Victoria. From a young emigrant seeking opportunity to a patriarch "universally respected" by his community. The twelve words of his death notice—"age 90, widower, 4 sons, 5 daus"—represent nearly a century of living, working, marrying, burying, and building.

Hugh Connors: A Life in Numbers

☘ The Nine Children

Hugh and Mary Henepy (Henesy) Connors raised nine children to adulthood on their farm at Lot 34. Four sons and five daughters—Bridget born in Newfoundland and the others born on Prince Edward Island, all carrying forward the legacy of County Wexford into a new world.

Children of Hugh Connors and Mary Henepy

The Kenny-Connors Intermarriage

Three of Hugh's children married into the Kenny family: Margaret married James Kenny (1866), Edward married Bridget Kenny (1867), and Bridget married the widowed Lawrence Kenny (1868). This triple alliance—detailed in Episode 5—bound the two families together across generations.

☘ The Last Will and Testament

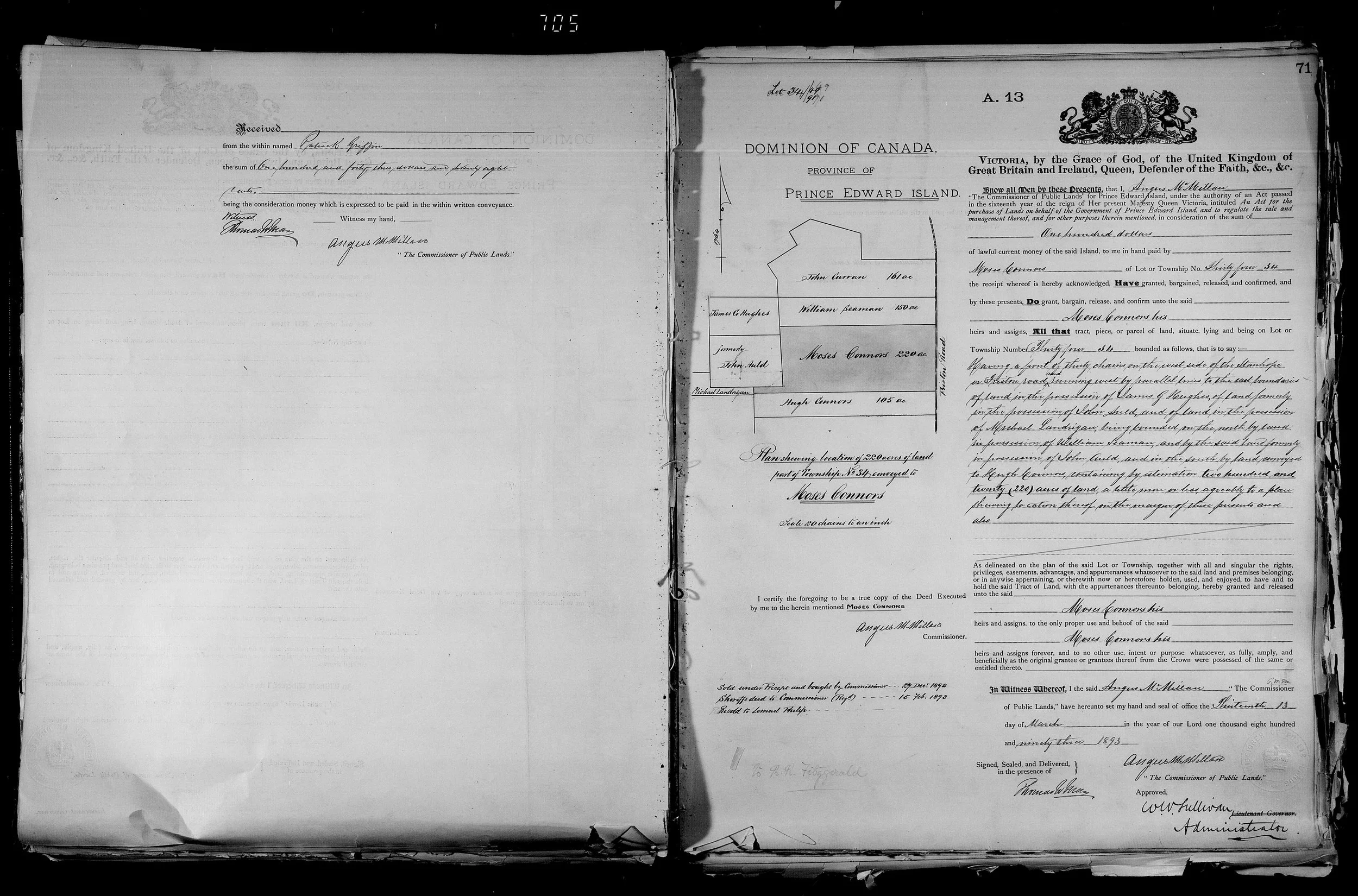

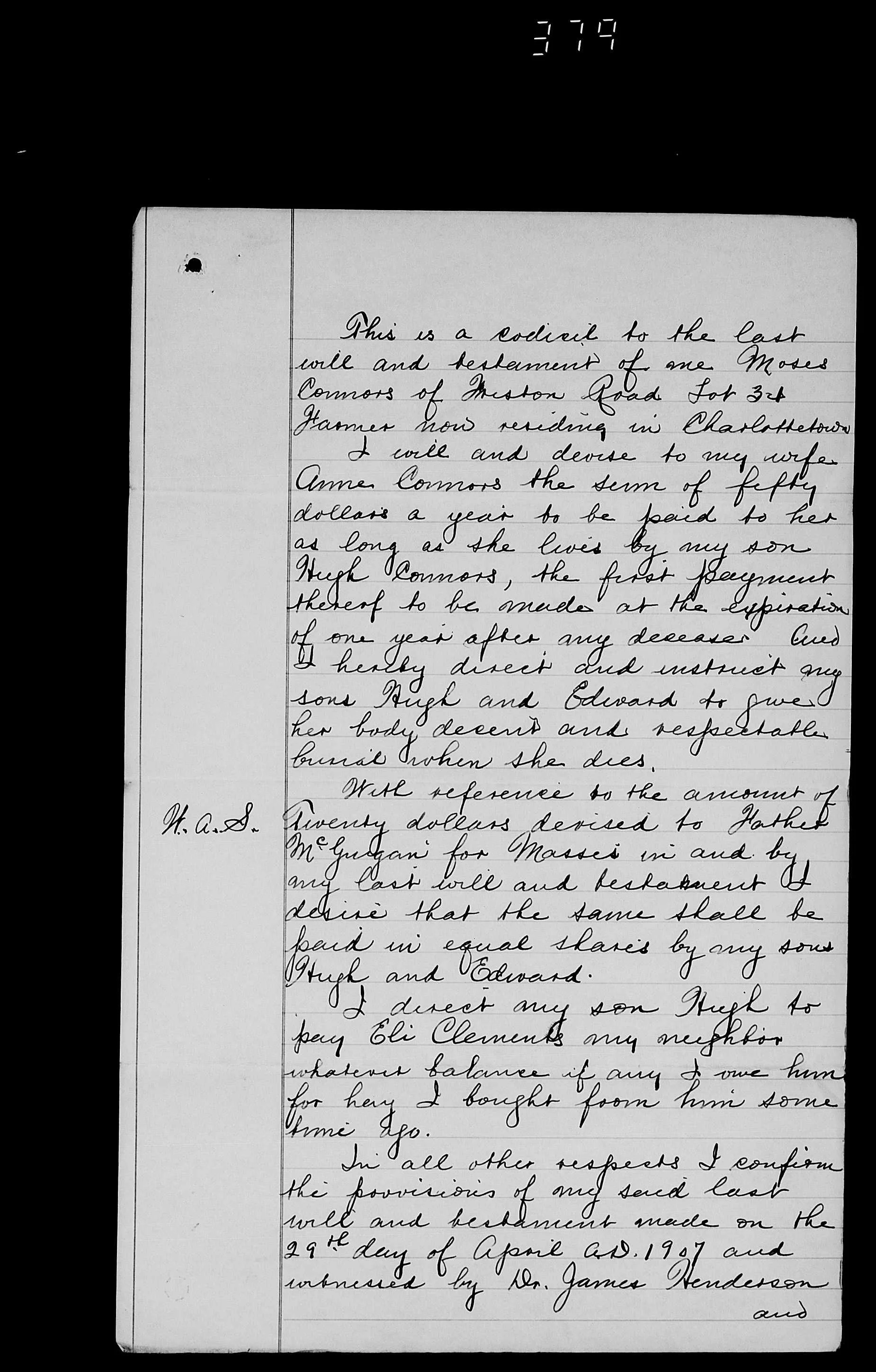

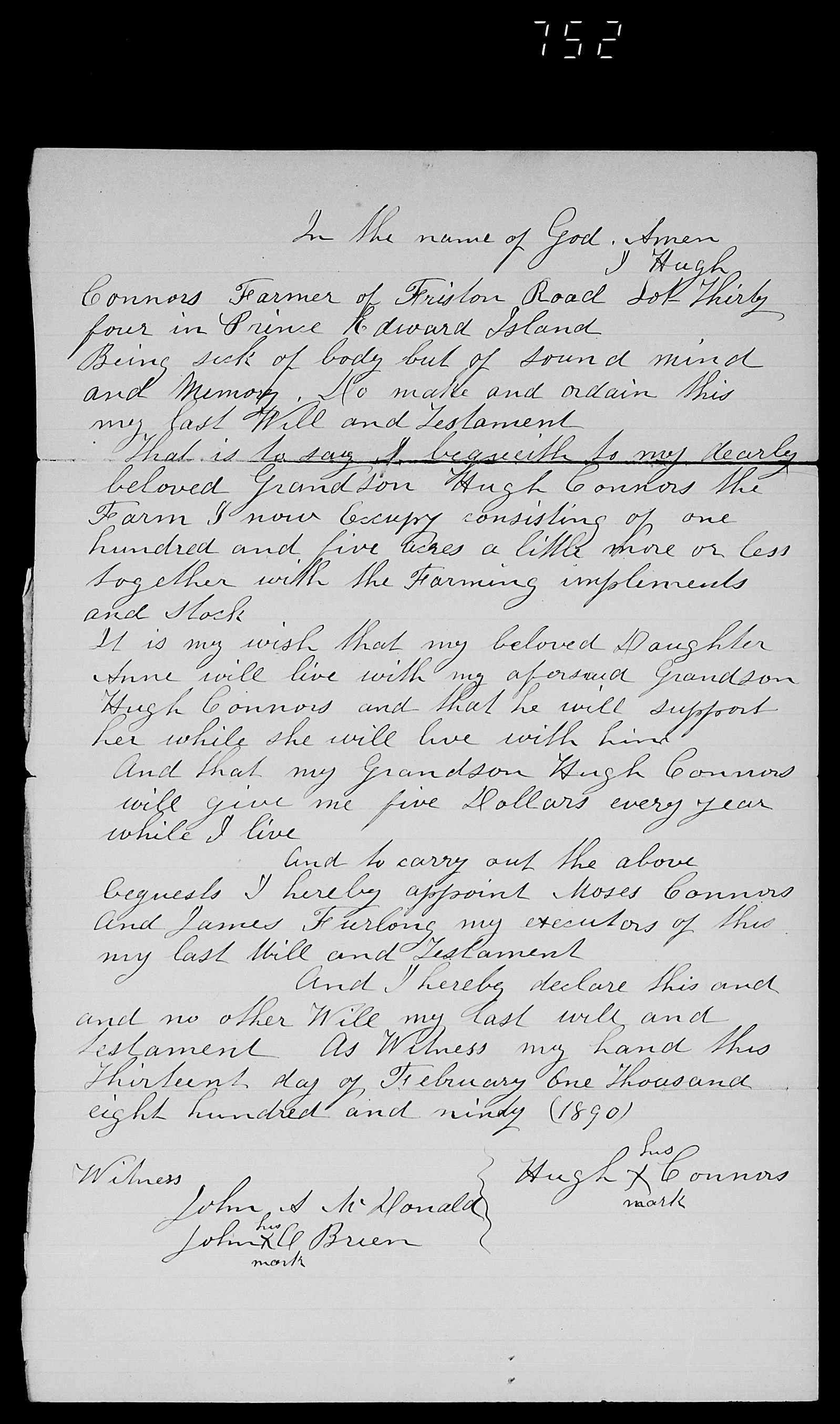

On February 13, 1890—nine months before his death—Hugh Connors dictated his last will and testament. He was "sick of body but of sound mind and Memory." Like his daughter-in-law Margaret Kenny, Hugh could not write; he signed with his mark. But his wishes were clear and carefully considered.

The will of Hugh Connors, dated February 13, 1890. "In the name of God. Amen. I Hugh Connors Farmer of Friston Road Lot Thirty four in Prince Edward Island Being sick of body but of sound mind and Memory do make and ordain this my last Will and Testament..."

I Hugh Connors Farmer of Friston Road Lot Thirty four in Prince Edward Island Being sick of body but of sound mind and Memory do make and ordain this my last Will and Testament

That is to say I bequeath to my dearly beloved Grandson Hugh Connors the Farm I now occupy consisting of one hundred and five acres a little more or less together with the Farming implements and Stock

It is my wish that my beloved Daughter Anne will live with my aforesaid Grandson Hugh Connors and that he will support her while she will live with him

And that my Grandson Hugh Connors will give me five Dollars every year while I live

And to carry out the above bequests I hereby appoint Moses Connors And James Furlong my executors of this my last Will and Testament

And I hereby declare this and and no other Will my last will and Testament As Witness my hand this Thirteenth day of February one Thousand eight hundred and nindy (1890)

Witness: John S. McDonald, John O'Brien [his mark]

Hugh X Connors [his mark]

Summary of Bequests

Why the Grandson?

Hugh left his farm not to his sons but to his grandson—Hugh Connors, son of Edward and Bridget Kenny Connors. This grandson Hugh was likely living on and working the farm in his grandfather's declining years. The arrangement preserved the family land while ensuring care for both the elderly patriarch (who would receive $5 annually) and the unmarried daughter Ann. By 1890, Hugh's sons Moses and David had their own established holdings; Edward's son was the logical heir to continue the original Connors homestead.

His Mark

☘ The Probate

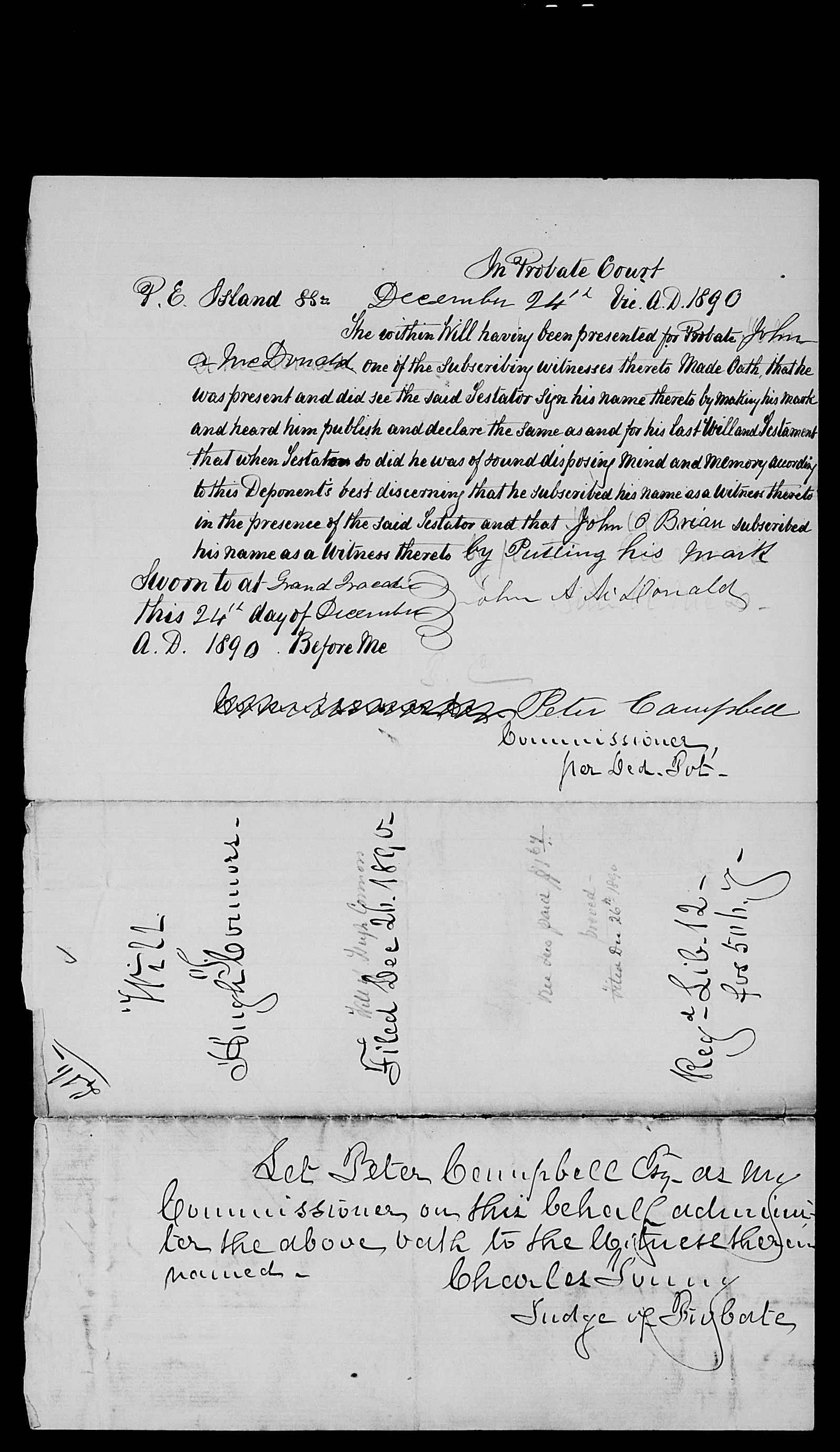

Hugh Connors died on November 22, 1890. One month later, on December 24, 1890, his will was presented for probate before Peter Campbell, Commissioner. John S. McDonald—one of the witnesses—testified that he had been present when Hugh made his mark, that Hugh was "of sound disposing Mind and Memory," and that John O'Brien had also witnessed by "Putting his mark."

The probate filing dated December 24, 1890, sworn before Peter Campbell, Commissioner. The will was filed December 26, 1890 and approved by Charles Young, Judge of Probate—the same judge who had handled the Estate of James Kenny eighteen years earlier.

The will was filed on December 26, 1890—Boxing Day—and approved by Charles Young, Judge of Probate. It was the same Charles Young who had granted Margaret Kenny Letters of Administration for her husband James's estate in 1873. Seventeen years later, Young was still on the bench, now processing the estate of Margaret's father.

☘ The Spinster Aunt

Among Hugh Connors' nine children, Ann alone remained unmarried. Born April 20, 1846, she was 44 years old when her father died. The 1881 census shows her living with her parents on Lot 34. By 1891, after her father's death, she was living with her widowed mother and her nephew Hugh—the grandson who had inherited the farm and the responsibility to "support her while she will live with him."

Ann's situation was not unusual for her time and place. Many families included a spinster daughter who remained at home to care for aging parents. What is notable is Hugh's careful provision for her future. He did not leave Ann money or land—she would have had difficulty managing either independently. Instead, he created a living arrangement that would protect her while preserving the family farm intact. Ann would have a home with her nephew for as long as she lived.

"It is my wish that my beloved Daughter Anne will live with my aforesaid Grandson Hugh Connors and that he will support her while she will live with him."

— Will of Hugh Connors, February 13, 1890☘ The Executor: Moses Connors

Hugh appointed his eldest son Moses as executor—a role Moses fulfilled and then some. By 1893, Moses had expanded his own holdings to 220 acres through a Crown land purchase at $100. The 1890 P.E. Island Directory lists both "Connors Hugh, far" and "Connors Moses, far" at Pleasant Grove (Lot 34), farming side by side as they had for decades.

The P.E. Island Directory listing both Hugh Connors and Moses Connors as farmers at Pleasant Grove, Lot 34, Queens County—"a farming settlement located in Lot 34, Queen's County. Distant from Charlottetown 10 miles. Mails Bi-weekly."

Moses himself would live until September 27, 1907, dying at age 72. His own will—far more complex than his father's—divided extensive holdings among his sons David, Hugh, and Edward, provided for his wife Ann Leary Connors, bequeathed $50 to daughter Mary Ann, and directed $20 for masses for the repose of his soul. Like his father, Moses signed with his mark.

The typed will of Moses Connors (1907) shows how far the family's fortunes had grown from Hugh's original 84-acre lease. Moses had already conveyed 145 acres to son David and still held 131 acres to distribute.

☘ Timeline: The Patriarch's Century

☘ The Legacy

Hugh Connors arrived on Prince Edward Island in 1832 with nothing but hope and the memory of County Wexford. By the time he died in 1890, he had built a 105-acre farm, raised nine children, and seen grandchildren born on three different continents. His daughter Margaret had taken the Kenny name to Chicago. His sons Moses and David were expanding the Connors holdings on Lot 34. His grandson Hugh—who bore his name—would carry forward the homestead into a new century.

The obituary called him "favorably known and universally respected." The will showed a man who thought carefully about his family's future, providing for his unmarried daughter while preserving the farm he had spent a lifetime building. The probate records reveal a community that functioned—neighbors witnessing documents, commissioners swearing oaths, judges approving transfers. Hugh Connors was part of that community for 58 years.

When he died, the world of his youth had vanished. The Ireland he left in 1832 was still under British rule, still reeling from the aftermath of the 1798 Rebellion that had convulsed County Wexford. The Prince Edward Island he found was a colony of tenant farmers struggling under the leasehold system. By 1890, Ireland was agitating for Home Rule, and PEI had been part of Canadian Confederation for seventeen years. Hugh had lived through the Great Famine (from a safe distance), the American Civil War, and the birth of modern Canada.

He had also lived long enough to bury his wife Mary, to see his son-in-law James Kenny die young, to watch his widowed daughter Margaret take her children to Chicago. The patriarch had outlived many of those he loved. But he had also provided for those who survived him—his grandson, his daughter Ann, his executors. The farm would continue. The Connors name would endure on Lot 34 for another generation.

Favorably Known and Universally Respected

The Summerside Journal's phrase was not mere obituary boilerplate. Hugh Connors had spent 58 years on Lot 34, building relationships with neighbors whose names appear throughout the documentary record—the Currans, the Furlongs, the McDonalds. These were the men who witnessed his will, served as executors, testified at probate. Hugh's "universal respect" was earned through decades of shared labor, worship at St. Eugene's, and the quiet accumulation of a life well-lived.

As Hugh Connors was laid to rest in Wexford's distant shadow, the family he had built was already transforming. His daughter Margaret was taking in washing in Chicago's Englewood neighborhood. His grandson Hugh would inherit the farm and the responsibility for Aunt Ann. His son Moses would expand the Connors holdings until they dwarfed the original 84-acre lease. And somewhere in Chicago, a boy named Hugh Daniel Kenny—Margaret's posthumous son, born seven months after his father James died—was growing up without any memory of the grandfather whose name he shared.

The Kenny-Connors alliance that Hugh had witnessed—three weddings in two years—had scattered across a continent. But the bonds forged on Lot 34 would endure. Every Kenny was also a Connors; every Connors was also a Kenny. And Hugh Connors, the Wexford emigrant who became a PEI patriarch, had made it all possible.

Primary Source Gallery

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY