Two Families, One Story : The Estate of James Kenny

The Estate of James Kenny

Six years after their wedding at St. Eugene's Church, Margaret Connors Kenny became a widow. James Kenny—the farmer of Lot 34, the son of Lawrence and Catherine Corcoran, the man who had married into the Connors family as part of that triple alliance of 1866-1868—died in the summer of 1872. He was approximately 40 years old. Margaret was pregnant with their fourth child.

What we know of James Kenny's death comes not from a death certificate or an obituary, but from the probate records filed in the Surrogate Court of Prince Edward Island. These legal documents—Margaret's petition, the administration bond, the estate inventory—tell a story of modest prosperity, legal complication, and a widow's determination to secure her children's future.

☘ The Twenty-Fifth Day of June

James Kenny died on or about June 25, 1872, on his leasehold farm on Covehead Road in Township 34. The cause of death is not recorded in the surviving documents. He left behind his wife Margaret and their three surviving children: Catherine (age 3), Lawrence (age 2), and Thomas (not yet 1). Margaret was pregnant with their fourth child.

The Kenny family gravestone at St. Eugene's Parish Cemetery, Covehead. The inscription reads: "Their Son JAMES / Died June 25, 1872 / Ae. 40" — commemorated on his parents' stone alongside Lawrence Kenny (d. Feb 20, 1899, Ae. 95) and Catherine Corcoran (d. Jan 23, 1855, Ae. 53).

James had attempted to prepare for the worst. On June 3, 1872—just three weeks before his death—he signed a paper "intended for his last Will and Testament." But the will was fatally flawed. As Margaret would later explain to the Surrogate Court, "the witnesses to the Said paper writing did not Sign the Same at the Same time or in the presence of Each other." Under Prince Edward Island law, the will was invalid. James Kenny died intestate.

A Will Without Effect

The timing suggests James Kenny knew he was dying. Three weeks before his death, he tried to put his affairs in order. But the legal technicality that invalidated his will—witnesses who didn't sign together in each other's presence—meant that Margaret would have to petition the court for Letters of Administration rather than simply execute her husband's wishes. This legal complication delayed settlement of the estate by over a year.

☘ The Humble Petition of Margaret Kenny

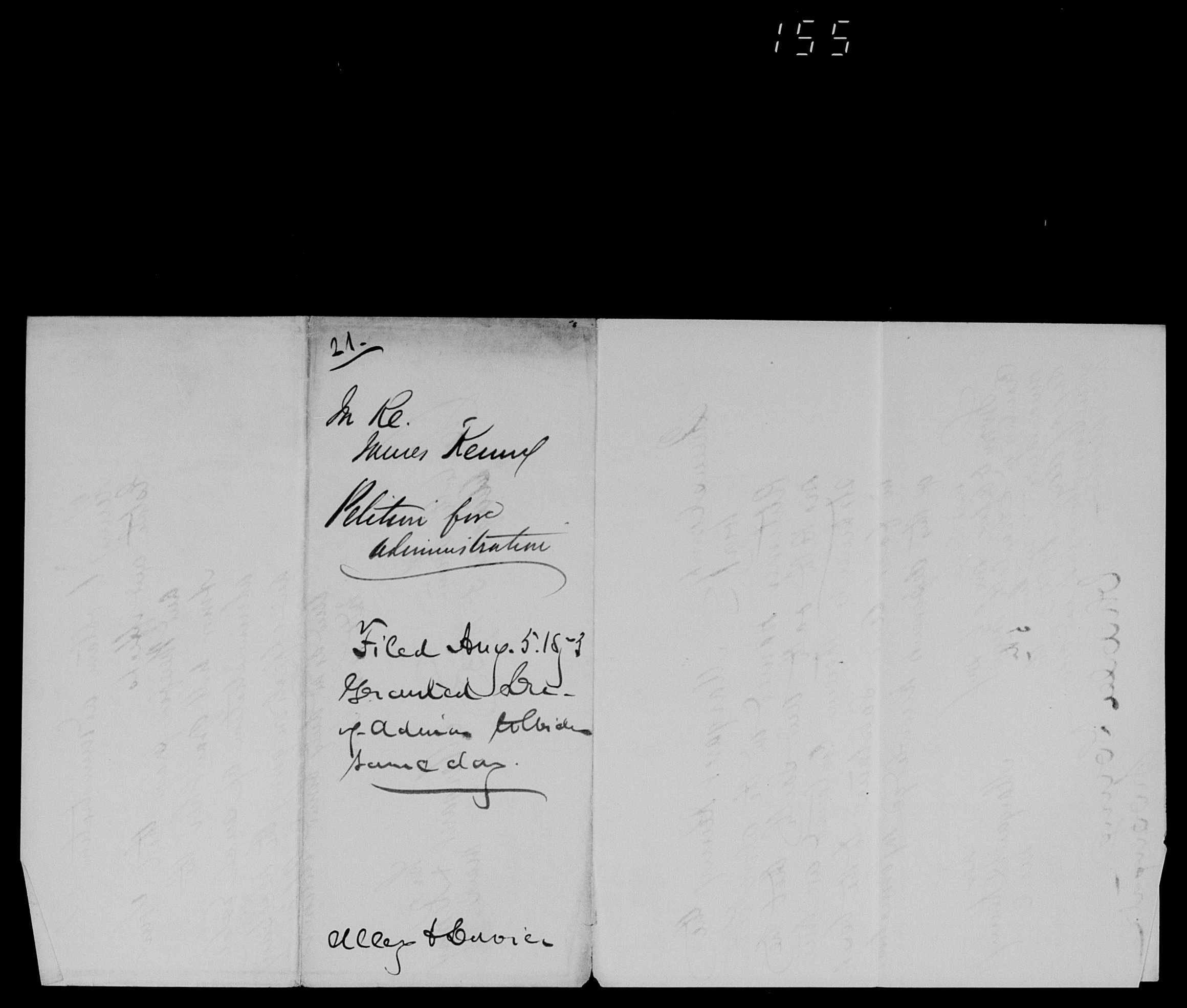

On August 5, 1873—more than a year after James's death—Margaret Kenny appeared before the Honorable Charles Young, Surrogate and Judge of Probate, to petition for Letters of Administration. The document she signed reveals both the facts of her situation and the legal language of 19th-century estate proceedings.

The first page of Margaret Kenny's petition to the Surrogate Court of Prince Edward Island, dated August 5, 1873. The document addresses "the Honorable Charles Young Surrogate and Judge of Probate."

Sheweth,

That James Kenny late of Lot or Township number Thirty four Farmer departed this life on or about the twenty fifth day of June last past leaving Your Petitioner his widow and three (3) sons and one daughter him surviving.

That previously to his death the Said James Kenny signed a paper writing intended for his last Will and Testament dated the third day of June 1872 but that the witnesses to the Said paper writing did not Sign the Same at the Same time or in the presence of Each other and deponent as advised and believes and that no other Will or other testamentary disposition was made by the Said James Kenny at any time previous to his death.

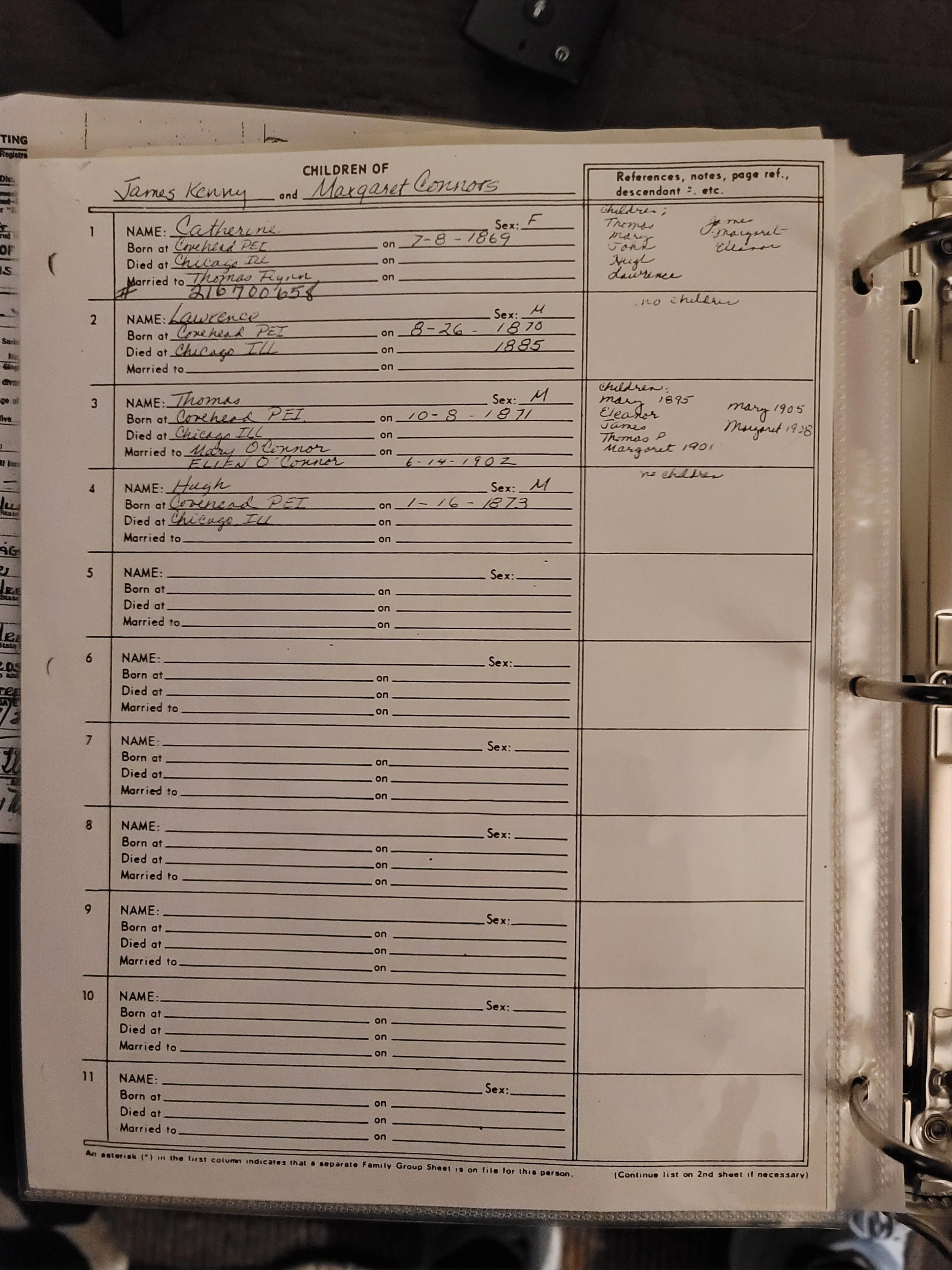

Note on the Children

The petition states James left "three (3) sons and one daughter." At the time of his death in June 1872, the children were: Catherine (daughter, b. July 8, 1869), Lawrence (son, b. August 26, 1870), and Thomas (son, b. October 8, 1871). The fourth child—Hugh Daniel—would not be born until January 16, 1873, nearly seven months after his father's death. The reference to "three sons" in August 1873 confirms Hugh had been born by the time the petition was filed.

☘ The Estate

Margaret's petition detailed the estate James left behind—a portrait of a tenant farmer's modest prosperity on Prince Edward Island in the 1870s.

Estate of James Kenny, Deceased

That there are certain debts and monies due to the Mid James Kenny the amount of which deponent believes to be very small but Cannot State with any degree of probable accuracy. And that there are Certain debts owing by the Mid James Kenny amounting as nearly as deponent Can ascertain to about the Sum of three hundred dollars

The estate's net value—approximately $1,050 after debts—represented a modest but respectable holding for a tenant farmer. The leasehold farm itself, valued at $850, was not owned outright; like most farmers on the Montgomery Estate, James held a long-term lease rather than fee simple title. This distinction would matter greatly when Margaret considered her options as a widow.

☘ Margaret's Mark

At the bottom of her petition, Margaret Kenny did not sign her name. She made her mark—an X—beside the words "Margaret Kenny." The same mark appears on the administration bond. Margaret Connors Kenny, mother of four, widow of a farmer, petitioner before the Surrogate Court, could not write her own name.

Her Mark

The petition pages showing Margaret Kenny's signature—an X mark—dated "Charlotte Town, August 5, 1873." The document was sworn before Charles Young, Surrogate.

This detail—easily overlooked in the legal formality of probate documents—speaks volumes about Margaret's situation. She was an Irish immigrant's daughter, raised on a tenant farm, married young to a neighboring farmer's son. Literacy was not universal in rural Prince Edward Island, and certainly not guaranteed for women of her generation and class. Yet this illiterate widow would navigate the colonial court system, secure her children's inheritance, and ultimately lead her family on a journey of 1,500 miles to build a new life in Chicago.

☘ The Sureties

To receive Letters of Administration, Margaret needed two sureties—men who would guarantee her faithful execution of her duties as administratrix. The administration bond, in the sum of Eight Hundred Pounds, was signed by Margaret and two neighboring farmers from Lot 34.

Sureties on the Administration Bond

The administration bond showing the signatures of Margaret Kenny (her mark), David Douglas, and Peter Curran, with official seals. These neighboring farmers vouched for Margaret's ability to administer her husband's estate.

The presence of David Douglas and Peter Curran on the bond tells us something important: the community of Lot 34 rallied around the young widow. These were not strangers performing a legal formality; they were neighbors who had likely known James Kenny, who attended the same church, who worked the same land under the same landlord. Their willingness to stake their own financial security on Margaret's faithful administration reflects the tight bonds of rural Irish-Catholic community on Prince Edward Island.

☘ The Posthumous Child

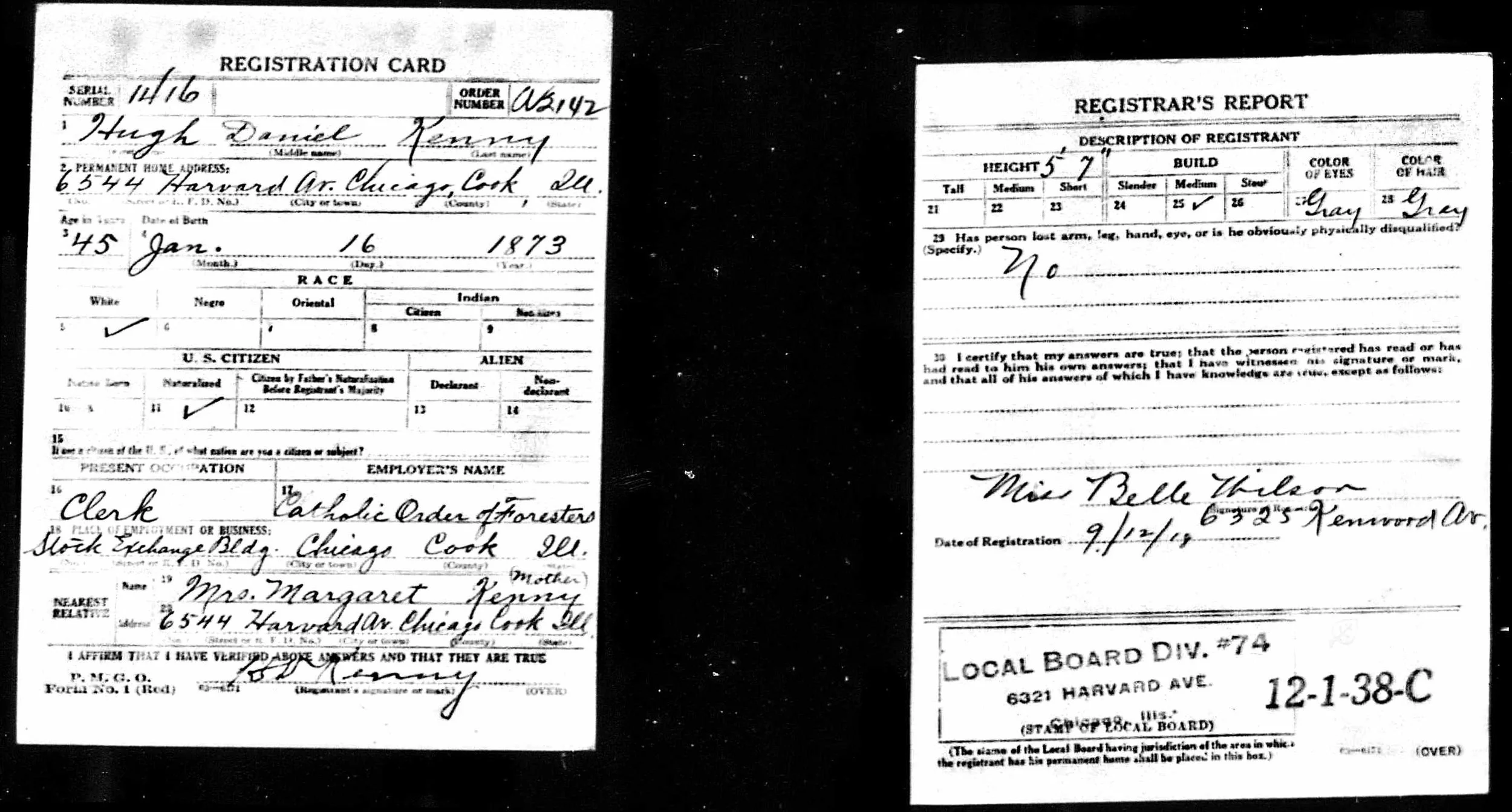

On January 16, 1873—six months and twenty-one days after James Kenny's death—Margaret gave birth to their fourth child. She named him Hugh Daniel Kenny.

The name was significant. Hugh was the name of Margaret's father—Hugh Connors, the patriarch who had emigrated from County Wexford in 1832, who still farmed his 84 acres (now expanded to 105) on Lot 34. By naming her fatherless son after her own father, Margaret honored the Connors line even as she mourned her Kenny husband.

Hugh Daniel Kenny's WWI Draft Registration Card (1918) confirms his date of birth as January 16, 1873. At age 45, he was working as a Clerk for the Catholic Order of Foresters in Chicago. His nearest relative is listed as "Mrs. Margaret Kenny (Mother)" at 6544 Harvard Ave, Chicago—proof that Margaret was still living with her youngest son 46 years after James's death.

No Birth Record Found

No baptismal or birth record for Hugh Daniel Kenny has been located in the St. Eugene's parish registers. His birthdate is confirmed through his WWI Draft Registration (which required documentation) and the Family Group Sheets compiled by M.E.M. Brady. The absence of a birth record is not unusual—parish registers from this period are incomplete, and the family's circumstances as recent mourners may have affected record-keeping.

☘ Timeline: 1872-1873

☘ What Margaret Faced

At 32 years old, Margaret Connors Kenny found herself a widow with four children under the age of five. Her assets included a leasehold farm valued at $850—land she didn't own, but merely rented from the Montgomery estate—and whatever remained of the $500 in personal property after paying approximately $300 in debts. She could not read or write. Her husband's attempt to provide for her through a will had failed on a legal technicality.

"Margaret supported her young family by taking in washing."

— Mary Ellen Molony Brady, family historianHer options were limited. She could remain on Lot 34, continuing to farm the leasehold land, relying on the support of her Connors family—her parents Hugh and Mary were still living, her siblings still nearby. She could remarry, as many widows did, seeking a new husband to provide for her children. Or she could leave Prince Edward Island entirely, seeking opportunity elsewhere.

According to family tradition preserved by M.E.M. Brady, Margaret chose the third option. In about 1877—five years after James's death—she "left Charlottetown... on a long journey up the St. Lawrence with her four small children." Her destination: Chicago, Illinois, where she would "join relatives named Murphy."

The first page of Mary Ellen Molony Brady's biographical sketch of Margaret Connors Kenny, documenting her journey from widowhood on Prince Edward Island to a new life in Chicago. The sketch notes she "lived to be 89" and was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois.

The probate records of James Kenny's estate are dry legal documents—petitions, bonds, inventories. But they preserve a moment of profound vulnerability in Margaret's life: the summer of 1872, when she lost her husband, and the year that followed, when she gave birth to a fatherless son, navigated the colonial court system, and began to contemplate a future beyond Prince Edward Island.

James Kenny was buried in St. Eugene's Parish Cemetery, his name added to his parents' gravestone: "Their Son JAMES / Died June 25, 1872 / Ae. 40." His widow would live another 53 years, dying in Chicago on July 21, 1925, at the age of 89. She never returned to Covehead.

Primary Source Gallery

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY