One Parish, Five Destinations

One Parish, Five Destinations

DNA doesn't lie, but it doesn't always explain itself either. As I've worked to untangle the Hamill families of Donaghmoyne parish in County Monaghan, I keep encountering the same puzzle: distinct clusters of DNA matches pointing to relatives in Chicago, Wisconsin, the Joliet area of Illinois, St. Louis, Missouri, and Anaconda-Deer Lodge in Montana. These matches trace back to ancestors who were married in the same small Irish parish between 1841 and 1858—yet their descendants ended up scattered across vastly different corners of America.

The geographic spread raises a fundamental research question: How do we prove that families who emigrated decades apart, to completely different destinations, were actually connected back in Ireland? And equally compelling: Why did members of what appears to be the same extended family network make such dramatically different choices about where to rebuild their lives?

The Core Research Challenge

We have DNA evidence suggesting connection. We have families from the same parish. But approximately 50 years and thousands of miles separate our earliest emigrants (1850 to Montreal and Wisconsin) from our latest (c. 1900 to Butte, Montana). How do we bridge that gap when documentation is sparse and spelling variations obscure the trail?

The Families: What We Know

Before we can solve the puzzle, we need to lay out the pieces. Five distinct Hamill family groups have emerged from records and DNA matching, all originating from Donaghmoyne parish in County Monaghan, Ireland. Three emigrated during or shortly after the Famine; two came later, from the same family that stayed behind.

Five Migration Paths from One Parish

The Montreal/Chicago Line

The Wisconsin/Nebraska Line

The Joliet, Illinois Line

The Montana Line

The Missouri Line

The timeline reveals the first major obstacle: we're dealing with at least a full generation gap between the Famine-era emigrants and the Montana and Missouri migrants. Henry Hamall's family fled Ireland around 1850, in the immediate aftermath of the Great Hunger. The Hamill-Gartlan family who eventually settled in Montana and Missouri didn't leave until the 1880s and 1900—after James Hamill Sr. had lived his entire life in Dian townland, dying in 1914 at age 87.

That 50-year span means we're not just connecting siblings or even first cousins who emigrated together. We're trying to link families across multiple generations, through a period when Irish record-keeping was inconsistent at best, and when the very spelling of "Hamill" could shift from document to document.

Why the Different Destinations?

Understanding why these families ended up where they did requires stepping back to examine the broader patterns of Irish emigration—and how those patterns shifted dramatically between the 1850s and 1900.

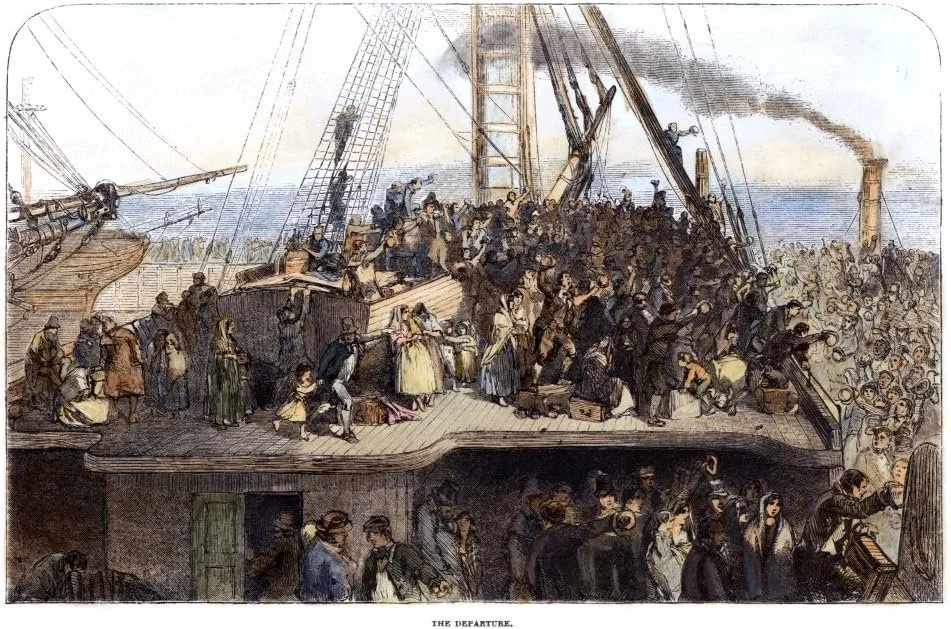

The 1850 Emigrants: Survival First

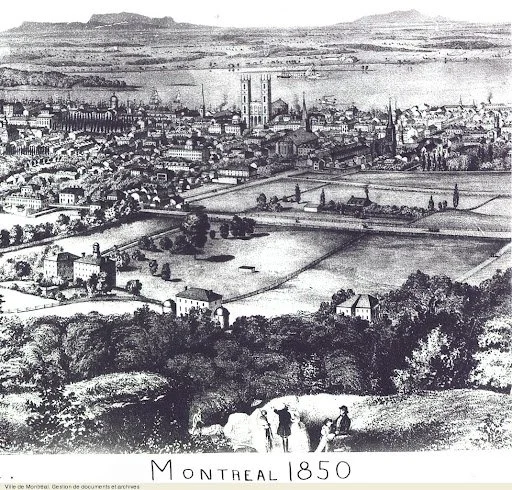

When Henry Hamall and Mary McMahon brought their young family to Montreal around 1850, they were part of the massive Famine exodus. The choice of Montreal wasn't primarily about opportunity—it was about survival. Passage to British North America was cheaper than to American ports, and British emigration policies actively encouraged settlement in Canada. The family's first priority was simply getting out of Ireland alive.

Montreal in 1850 was still reeling from the "ship fever" typhus epidemic of 1847, when thousands of Irish emigrants had died in quarantine at Grosse Isle or in the city's fever sheds. But it was also developing into a significant industrial center, with foundries and manufacturing operations that would employ workers like Owen Hamall when he came of age. The trajectory from Montreal to Chicago followed established Irish Catholic networks—moving inland where wages were higher and discrimination less intense than in the crowded Eastern ports.

The Owen Hammel family who settled in Rock County, Wisconsin by 1850 followed a different but equally urgent pattern. Wisconsin offered something Montreal couldn't: the prospect of land ownership. Irish labor was in high demand for America's infrastructure boom, and homesteading opportunities in the upper Midwest gave families a chance to build something permanent. Owen's death in 1858 left his family to carry on without him, eventually establishing themselves in Nebraska by the 1880s.

The 1860 Emigrant: The Canal Irish

Susan Hamill and Charles McCanna, who emigrated around 1860 and settled in Joliet by 1862, represent the "canal Irish" migration pattern. By this point, the immediate crisis of the Famine had passed, but economic conditions in Ireland remained dire. The pull factors had shifted: Irish labor was now in high demand for America's infrastructure boom.

Joliet and Will County, Illinois, had become an Irish stronghold thanks to the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Construction had begun in 1836, drawing thousands of Irish laborers—the "canal Irish"—many of whom had previously worked on the Erie Canal. When the I&M Canal faced financial crises, workers were sometimes paid in "scrip" that could be exchanged for state-owned land, allowing former laborers to become farmers and permanent residents.

By the time Susan Hamill's family reached Joliet in the 1860s, the canal was complete, but the Irish community was firmly established. The area had transitioned to limestone quarrying, railroad work, and eventually steel manufacturing—all industries that would employ generations of Irish immigrant families.

The Post-Famine Emigrants: Following Opportunity

The children of James Hamill Sr. and Ann Gartlan represent an entirely different kind of Irish migration—one born of choice rather than desperation. James Sr. stayed in Dian townland, appearing in Griffith's Valuation in 1861, and lived until 1914. His sons Patrick Joseph (born 1862) and James Jr. (born 1874) grew up in an Ireland that, while still poor, was no longer in the grip of famine.

Patrick Joseph left first, arriving in the United States by 1881 and eventually settling in St. Louis. The city's French-Catholic heritage made it more welcoming to Irish Catholics than many Protestant-dominated cities, and its position as a railroad hub offered steady industrial employment. By the time he married Catherine Barry in 1893, St. Louis had become a thriving metropolis of over 450,000 people.

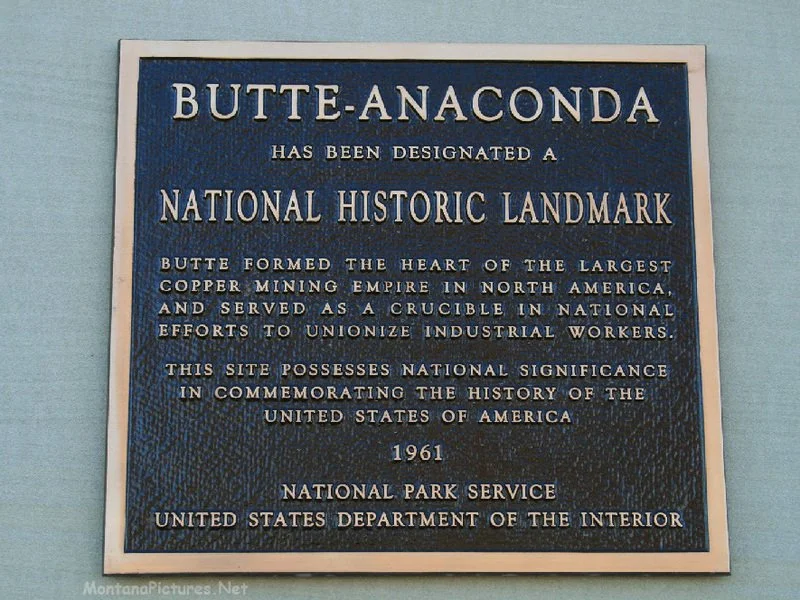

James Jr. followed a different path, arriving in Butte, Montana by 1900. By the turn of the century, Butte had earned its reputation as "the most Irish city in America"—and for good reason. The copper mines required hard-rock mining expertise, a skill set common in parts of Ireland with mining traditions. More importantly, one of the "Copper Kings," Marcus Daly, was himself an Irish immigrant from County Cavan who actively recruited Irish workers for his Anaconda operations.

Chain migration played a crucial role. Once a few families from a particular Irish parish established themselves in Butte, they sent word back home, and relatives followed. The Hamill-Gartlan connection represents exactly this pattern: a family that stayed in Donaghmoyne for decades after the Famine emigrants left, finally making the journey when the Montana copper industry offered wages that couldn't be matched in rural Ireland.

What the DNA Tells Us

The DNA evidence forms a compelling but complex web. From my line (descendants of Henry Hamall), the strongest matches connect to the Owen Hammel (Wisconsin/Nebraska) and Susan Hamill/McCanna (Joliet) descendants. One solid 4th-6th cousin match on a separate testing platform connects to the Montana Hamills—and critically, this match triangulates with both Owen Hammel and Susan Hamill descendants.

Through collaborative research with a direct descendant of the Montana line, an interesting pattern has emerged: we don't match each other directly, but we share matches in common pointing back to Monaghan—many with Gartlan connections. This "shared matches without direct match" pattern suggests the connection is real but may run through a collateral line (cousin, uncle) rather than direct descent, or simply falls at the edge of detectable DNA inheritance given the generational distance.

The convergence of evidence is too strong to dismiss: same parish, same time period, overlapping match pools all pointing to Donaghmoyne and the interconnected Hamill-Gartlan network. Four couples married in Donaghmoyne between 1841 and 1858 appear connected through this DNA cluster analysis: Henry Hamall & Mary McMahon (1841), Owen Hammel & Ann King (1846), Susan Hamill & Charles McCanna (1856), and James Hamill & Ann Gartlan (c. 1857). The Missouri line through Patrick Joseph Hamill shows strong DNA connections to the Montana line (his brother's family)—the gap is specifically between Henry's Chicago line and the James Hamill-Gartlan descendants.

View the marriage records for all four couples → (Document Gallery - Irish Origins & DNA Evidence)

Are You a Hamill Descendant?

If you descend from any Hamill, Hamall, Hammel, or Hamel family with roots in County Monaghan—particularly Donaghmoyne parish—I'd love to hear from you. Whether your ancestors settled in Chicago, Wisconsin, Nebraska, Illinois, Missouri, Montana, or anywhere else, your DNA test results and family records could be the missing piece that connects these scattered families. The more descendants who test and share, the clearer the picture becomes.

Research Strategies: Bridging the Gap

1. Work Backward from Griffith's Valuation

The 1861 Griffith's Valuation provides our most detailed snapshot of who remained in Donaghmoyne after the Famine emigrants left. James Hamill in Dian is confirmed. But the earlier Tithe Applotment Books (1823-1838) might show Henry, Owen, Susan, and James's father—or at least reveal the townland holdings that would establish their relationship.

- Cross-reference Dian, Drumaconvern, and Edengilrevy townlands

- Look for "Henry Hamil Edengilrew" in 1824 Tithe (possibly our Henry's father or uncle)

- Map all Hamill landholders to establish family clusters

2. Parish Records Deep Dive

Donaghmoyne Catholic parish records survive from the early 1800s. While we have the marriage records for four of our couples, we need to find baptismal records that would establish sibling relationships.

- Search for baptisms of Henry, Owen, Susan, and James Hamill (c. 1815-1830)

- Identify parents' names on baptismal records

- Look for sponsor patterns that reveal family connections

3. American Naturalization Records

Naturalization papers sometimes contain crucial details about Irish origins. Owen Hamall's 1872 Chicago naturalization gives us a model—but we need similar documents for the other lines.

- Search Will County, IL naturalizations for McCannas

- Check St. Louis records for Patrick Joseph Hamill

- Check Deer Lodge County, MT for James Hamill Jr. papers

4. Cemetery and Death Record Analysis

Death certificates and grave markers sometimes preserve family information lost elsewhere. Parents' names, specific birthplaces, and even ages can help establish generational relationships.

- Locate Montana death certificates for Hamill-Gartlan family

- Find Patrick Joseph Hamill's 1944 St. Louis death record

- Compare stated birthplaces and parents' names across all lines

5. DNA Triangulation

The DNA matches we have suggest connection, but triangulation could prove it. If descendants from all five lines share DNA with the same distant Irish cousins, we've established a common ancestor.

- Identify Irish matches who descend from Donaghmoyne families

- Priority: Find DNA testers descended from the Missouri line

- Use the Gartlan matches as a control group

6. Occupational Tracking

Following trades and occupations can reveal family connections when names fail. If multiple Hamills were molders, miners, or worked in specific industries, the pattern may indicate shared family training or connections.

- Track Owen Hamall's molder career in Chicago directories

- Examine Montana and Missouri employment records

- Look for occupational patterns across all five lines

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

This research challenge isn't unique to the Hamill family. Thousands of genealogists face the same puzzle: DNA suggests connection, geography suggests origin, but the documentary trail is fragmented across time, space, and spelling variations. The strategies we develop for the Hamills can serve as a template for similar Irish genealogy challenges.

What makes this case particularly instructive is the 50-year emigration span. We're not just tracking one wave of emigration—we're seeing how the same family network responded to dramatically different historical moments. The Famine emigrants of 1850 had no choice; they fled or died. The turn-of-century emigrants chose opportunity, following established networks to places where Irish labor was valued and Irish communities were thriving.

Key Research Observations

- Time gaps don't disprove connection — Families from the same parish emigrated across multiple generations, with those who stayed maintaining the family presence in Ireland

- Destination differences reflect historical moment — 1850 emigrants went where survival was possible; 1880-1900 emigrants followed labor markets and established communities

- Siblings took different paths — James Jr. went to Montana while Patrick Joseph chose Missouri, demonstrating that even brothers could end up 1,500 miles apart

- DNA clusters across geography — Matches in Chicago, Wisconsin, Illinois, and Montana all trace to Donaghmoyne marriages between 1841-1858, suggesting a common extended family network

- Documentary links fill DNA gaps — The Missouri line has no DNA match yet, but parish and civil records establish the sibling relationship to the Montana line

- Irish records may hold the key — Pre-Famine records like Tithe Applotments could establish the parental generation that links all five lines

Next Steps

This post represents the beginning of a focused research effort, not its conclusion. The path forward requires systematic work through the strategies outlined above, with particular attention to the pre-Famine Irish records that might establish the parental generation. I'll be documenting the results as the research progresses.

The DNA pattern we're seeing—strong matches to some lines, shared matches pointing to Monaghan across others, Gartlan connections threading through multiple clusters—suggests these families were all part of an interconnected community in Donaghmoyne. But DNA alone can't tell the whole story. We need more descendants to test, more family bibles and letters to surface, more collaboration across the scattered branches of this family tree.

If you have Hamill, Hamall, Hammel, McCanna, Gartlan, or related family connections to Donaghmoyne, County Monaghan—whether your ancestors ended up in Chicago, Wisconsin, Nebraska, Illinois, Missouri, Montana, or anywhere else—please reach out. Your DNA results, your family stories, your old photographs might hold the key that unlocks this puzzle for all of us.

Part of a Larger Story

This migration research is one piece of a much larger investigation into the Hamall family of Donaghmoyne. If you'd like to explore more, these resources trace the family from County Monaghan through five generations in America:

The Hamall Line

Documentary Biography Series

From County Monaghan to Riverside, Illinois — A young Irish father who died four years after reaching safety. Four children lost in eighteen months. A cottage protected through the Illinois Supreme Court. Five generations traced through famine, emigration, tragedy, and resilience.

Episodes: Henry Hamall — The Father Who Crossed the Ocean • Owen Hamall — The Iron Molder of Chicago • Thomas Henry Hamall — The Sole Surviving Son • Thomas Eugene Hamall — The Father Who Tried • Thomas Kenny Hamall — Young Life

The Owen Hamall Mystery

BCG Case Study

BCG-compliant DNA analysis validating Henry Hamall and Mary McMahon as Owen's parents, plus four interconnected Irish couples from Donaghmoyne parish. This case study demonstrates how DNA evidence corroborates documentary research when traditional records are incomplete.

Includes: DNA Evidence Analysis • Four-Couple Validation • Methodology Documentation • Primary Source Gallery

The Journey Continues

From thatched cottages in Monaghan to the foundries of Chicago, the farms of Wisconsin, the quarries of Joliet, the railroads of St. Louis, and the copper mines of Butte—the Hamill story spans continents and generations. The DNA tells us they're connected. Now we need more descendants to test, more records to surface, and more collaboration to prove it. If you're part of this story, reach out.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY