The 1863 Lake Map: A Cartographic Treasure

The 1863 Lake Map

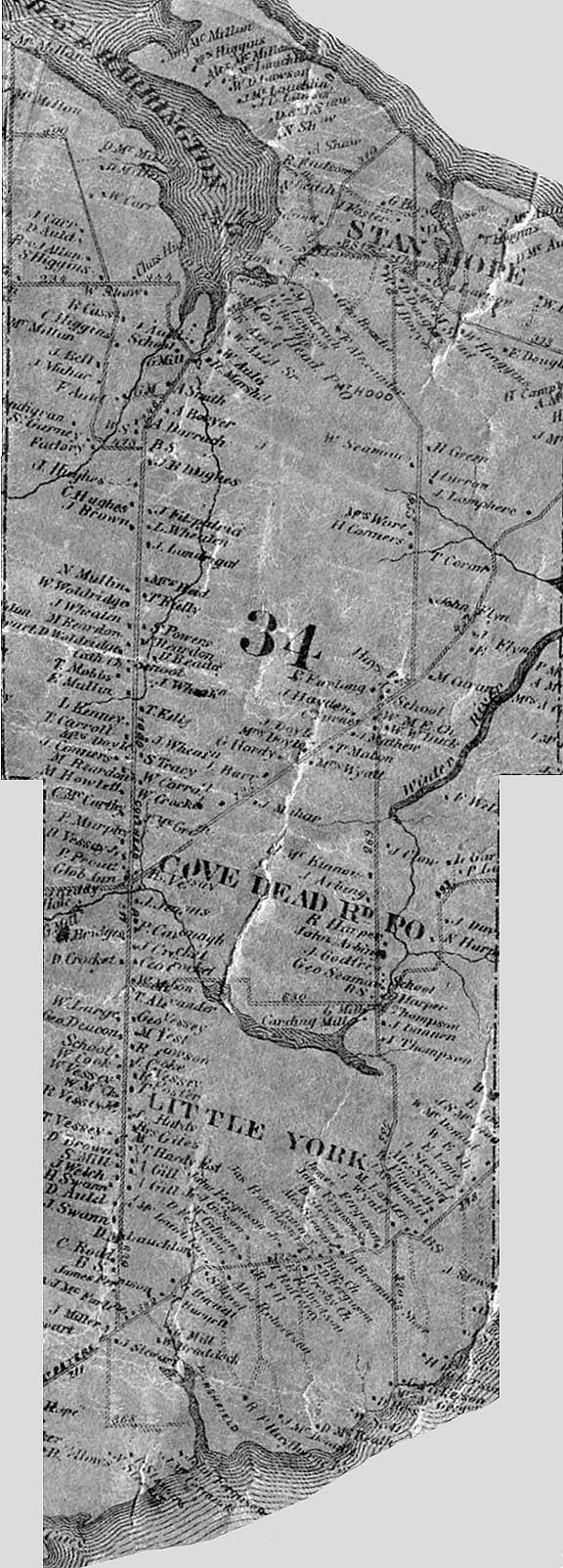

The first commercial map to record the names of individual property owners—and the document that places "L. Kenny" and "H. Connors" as neighbors on Lot 34.

For genealogists researching Prince Edward Island, the 1863 Lake Map represents a holy grail: the first time individual tenant farmers were recorded by name on a commercial map. When I located "L. Kenny" and "H. Connors" on neighboring properties in Lot 34, I was looking at documentary proof of what the parish registers had suggested—these families lived close enough to walk to each other's farms.

Lot 34 on the 1863 Lake Map, showing "L. Kenny" on Covehead Road and the Connors property nearby. The families whose children would marry three times over were already neighbors.

The Lake Map is more than a genealogical resource—it's a snapshot of Prince Edward Island on the eve of Confederation, capturing thousands of names, property boundaries, churches, schools, mills, and post offices at a moment when the Island was still divided between tenant farmers and absentee landlords.

☘ The Making of a Masterpiece

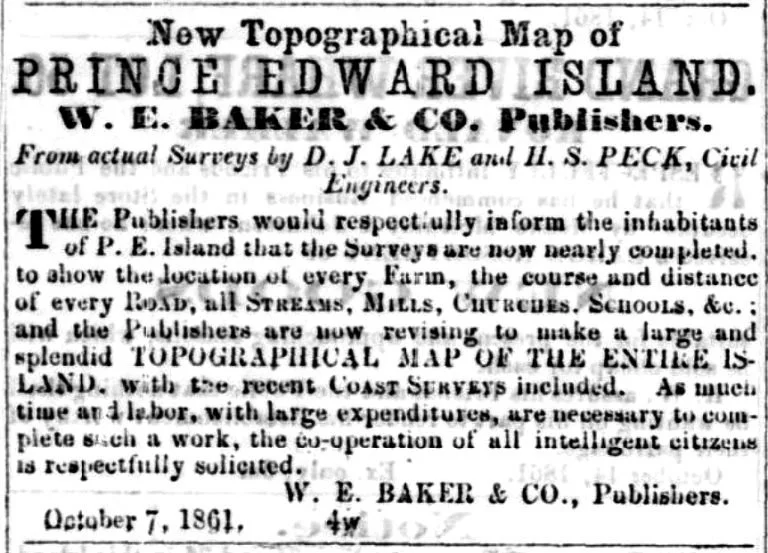

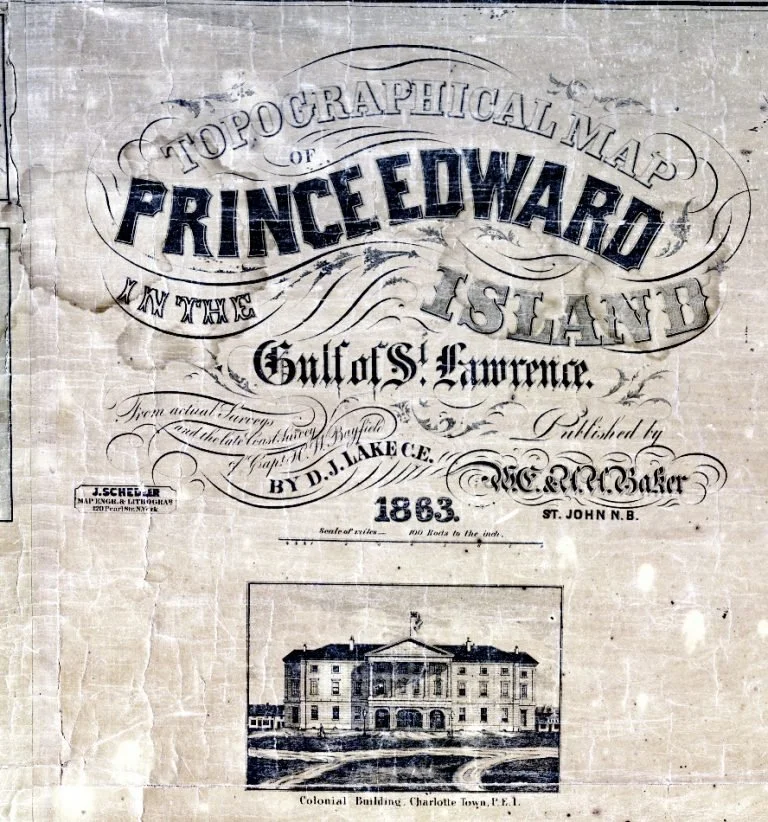

The map was the work of D. Jackson Lake, an American civil engineer from Newtown, Connecticut, who brought experience from similar large-scale county maps in the United States. Published by W.E. & A.A. Baker of Saint John, New Brunswick, the project took over two years to complete.

October 7, 1861

First advertisement appears in the Daily Examiner, announcing that surveys are "nearly completed" and soliciting subscribers.

June 2, 1863

The Daily Examiner publishes a detailed preview: "Every road is being carefully surveyed by course and distance... the location of every house on the Island, with the name of the owner."

August 17, 1863

The completed map is unveiled. "We have been shown this morning the new map of Prince Edward Island just completed."

November 26, 1863

Final copies available at the Reading Room in Charlottetown for those who had not yet received theirs.

The October 1861 advertisement in the Daily Examiner announcing the map project—originally attributed to both D.J. Lake and H.S. Peck, though only Lake's name appears on the final cartouche.

☘ A Commercial Masterpiece

The Lake Map followed a business model perfected in the United States: the map paid for itself before it went to press. Individuals and communities subscribed to have their names, properties, businesses, and town plans included. At 30 shillings per copy (roughly equivalent to $195 today), it was a significant investment—but for those who purchased it, a permanent record of their place in Island society.

Map Specifications

Size: Approximately 4 × 6 feet (48" × 72½")

Format: Large-scale lithograph mounted on wooden rollers for wall display

Data Sources: Original field surveys combined with Captain H.W. Bayfield's coastal surveys and 1861 Census data

Content: Property owners, roads, churches, schools, mills, streams, post offices, and 25 detailed community inset maps

The ornate cartouche featuring Province House, based on a photograph by Charlottetown photographer George P. Tanton. A second edition corrected the omission of Tanton's credit.

The map's production involved a team of surveyors traveling throughout the Island, consulting government records, and cross-referencing the 1861 Census to locate every property owner. The master design was drawn onto a polished limestone slab by J. Schedler of New York, then printed using the lithographic process that had revolutionized cartography in the mid-nineteenth century.

☘ Lot 34: Covehead and the Royalty

For the Kenny-Connors family history, the Lake Map's depiction of Lot 34 is invaluable. This township, part of Charlotte Parish in Queens County, encompassed the communities of Covehead, Stanhope, and York—all under the control of the Montgomery Estate.

Finding the Families on Lot 34

The map clearly shows "L. Kenny" (Lawrence Kenny) on Covehead Road and "H. Connors" (Hugh Connors) on Friston Road—the two families whose children would marry three times over between 1866 and 1868. They were neighbors, their properties separated by the roads their children walked to church, to school, and eventually to court each other.

The Lake Map records the Covehead Road Post Office serving the area, along with schools, churches, and the "Carding Mill" that processed wool from local farms. The detail is extraordinary—you can trace the exact configuration of roads that Hugh Connors and Lawrence Kenny would have traveled to reach Charlottetown, the county seat visible in the detailed inset map.

| Feature | Details on the Lake Map |

|---|---|

| L. Kenny | Located on Covehead Road, Lot 34 |

| H. Connors | Located on Friston Road, Lot 34 |

| Covehead Road P.O. | Post office serving the community |

| Carding Mill | Near Covehead, processing local wool |

| Schools | Multiple district schools indicated |

| Stanhope | Adjacent beach community |

☘ Charlottetown and the Royalty

The Lake Map includes a magnificent inset plan of Charlottetown, the colonial capital, showing every street, public building, and private residence. For genealogists, this offers a glimpse into the urban world that rural families like the Kennys and Connors would have encountered when traveling to town for business, church festivals, or legal matters.

The term "Royalty" appears on the map, designating the area surrounding Charlottetown that was reserved by the Crown for urban expansion. Unlike the rest of the Island, divided into proprietary lots owned by absentee landlords, the Royalties were Crown land—a distinction that affected settlement patterns and land tenure throughout the colonial period.

The Three Original Royalties

Queens Royalty: Centered on Charlottetown, the colonial capital

Kings Royalty: Centered on Georgetown

Prince Royalty: Centered on Princetown (now Malpeque)

These areas were surveyed with a grid pattern of small town lots surrounded by larger "pasture lots" for future expansion—an Enlightenment-era vision of orderly colonial development.

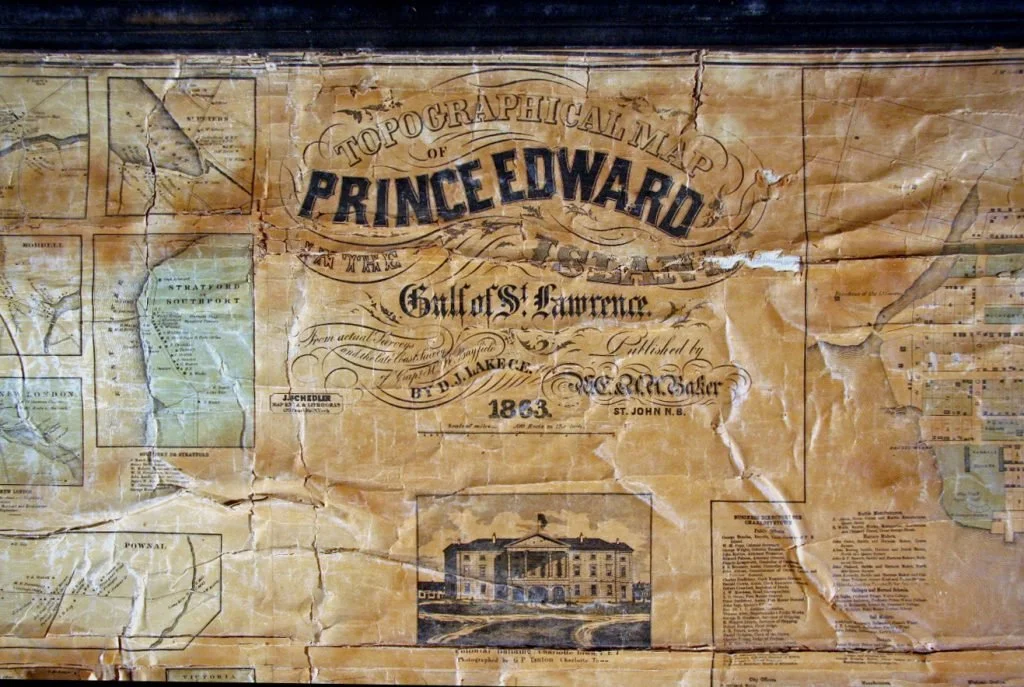

☘ Preservation and Access Today

The Lake Map was designed for heavy use, with a varnished surface to protect against the oily, sooty hands of nineteenth-century users. Unfortunately, that same varnish—a chemically unstable compound—has darkened over time, becoming brittle and cracked. Many surviving copies show fungal stains from damp storage, creases from repeated rolling, and missing portions where the lacquered paper flaked away.

The cartouche of a surviving Lake Map, showing the characteristic yellowing of the varnish and damage from over 160 years of use.

The primary surviving public copy is held at the Robertson Library, University of Prince Edward Island. To prevent further deterioration, the map has been digitized and is now accessible online through multiple platforms.

☘ Access the Lake Map Online

Island Imagined (UPEI)

High-resolution digital scan of the entire map with zoom functionality. The most detailed online version available.

The Island Register

Lot-by-lot sections of the map, plus transcriptions of names, directories, and census data. Click on any lot number to view that section.

Library and Archives Canada

Holds the map in 4 sheets (Reference: H1/204/1863). Includes full cataloging information.

☘ Using the Lake Map for Genealogy

For anyone researching PEI ancestors in the mid-nineteenth century, the Lake Map is an essential starting point:

Research Tips

1. Locate your ancestor's property — Names are shown at the approximate location of each farm or residence.

2. Identify neighbors — Neighbors were often extended family, witnesses at weddings, or godparents at baptisms. The families surrounding your ancestor may hold clues.

3. Compare with the 1880 Meacham's Atlas — Tracking the same property across both maps (17 years apart) reveals inheritance patterns, property transfers, and family movements.

4. Note community features — Churches, schools, mills, and post offices help establish the social world your ancestors inhabited.

5. Use the inset town plans — If your ancestor had business in Charlottetown, Georgetown, or Summerside, these detailed maps show the streets they walked.

The Lake Map, combined with the 1880 Meacham's Atlas and the 1926 Cummins Atlas, allows genealogists to follow three generations of a family across 65 years of Island history—watching as tenant farmers became freeholders after the Land Purchase Act of 1875, and as children inherited (or left) the farms their parents had worked.

Continue the Documentary Biography

This companion piece accompanies the Kenny-Connors Documentary Biography Series. Episode 4, "Covehead," explores Hugh Connors' settlement on Lot 34 in detail—using the Lake Map and Meacham's Atlas to trace how the Kenny and Connors families became neighbors.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY