Scattered Stones Prologue: The Land They Left

← Scattered Stones: Series Overview

SCATTERED STONES • PROLOGUE

The Land They Left

The World of Bendochy and Blairgowrie

Perthshire, Scotland

"To understand why a family left, you must first understand what they left behind."

Before we follow the Robertson family across the Atlantic, before we trace their scattered paths through Brooklyn and Georgia and New Jersey, we must begin where they began: in a corner of Scotland where the Highlands meet the Lowlands, where rivers carve through ancient rock, and where the name Robertson has echoed for centuries.

This prologue is both a geography lesson and a genealogical primer—an introduction to the land, the parish system, and the records that allowed us to reconstruct the lives of ordinary Scots who left extraordinary paper trails.

Robertson Country

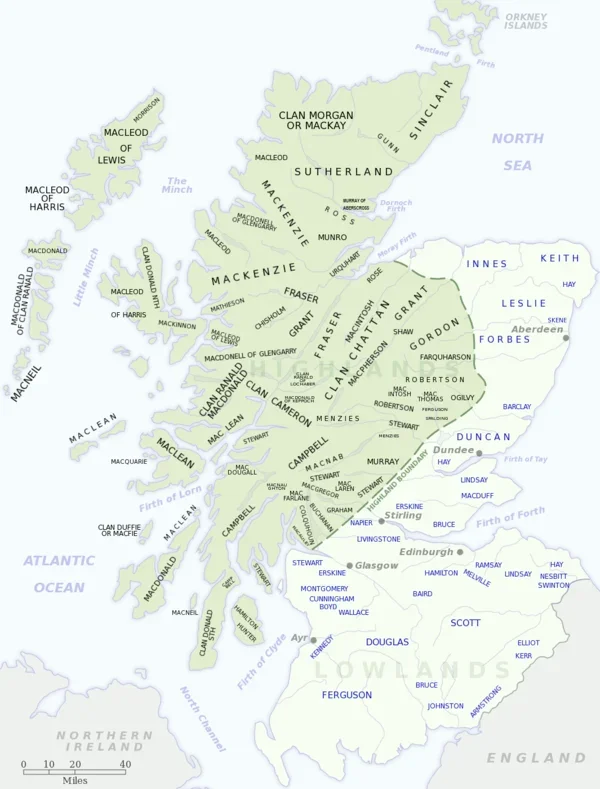

Scottish Clan Territories. Clan Robertson (Clann Donnachaidh) occupied the central Highlands,

with Perthshire at its heart. Map: Wikipedia.

Look at a map of Scottish clan territories and you'll find Clan Robertson—known in Gaelic as Clann Donnachaidh, "Children of Duncan"—occupying the central Highlands. Their territory stretched across Perthshire, from the shores of Loch Rannoch to the fertile valley of Strathmore. This was Robertson country.

By the nineteenth century, the clan system had largely faded as a political force, but the name endured. In the 1881 census of Blairgowrie—the market town where George Robertson raised his family—Robertson was the most common surname. Of the 5,000+ residents, 253 were Robertsons: one in every twenty people. The second most common name, Stewart, had barely half as many.

Our Robertsons weren't clan chiefs or landed gentry. Duncan Robertson was a weaver; his son George became a mason. They were working people in a land where their surname was as common as Smith or Jones in England. Yet their ordinariness is precisely what makes their story recoverable—they left traces in the same parish registers, census returns, and vital records as their neighbors.

Most Common Surnames in Blairgowrie, 1881

| Rank | Surname | Count | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Robertson | 253 | 1 in 20 |

| 2 | Stewart | 144 | 1 in 36 |

| 3 | Anderson | 84 | 1 in 62 |

| 4 | Young | 78 | 1 in 66 |

| 5 | Ferguson | 76 | 1 in 68 |

Source: 1881 Census of Scotland

The Parish of Bendochy

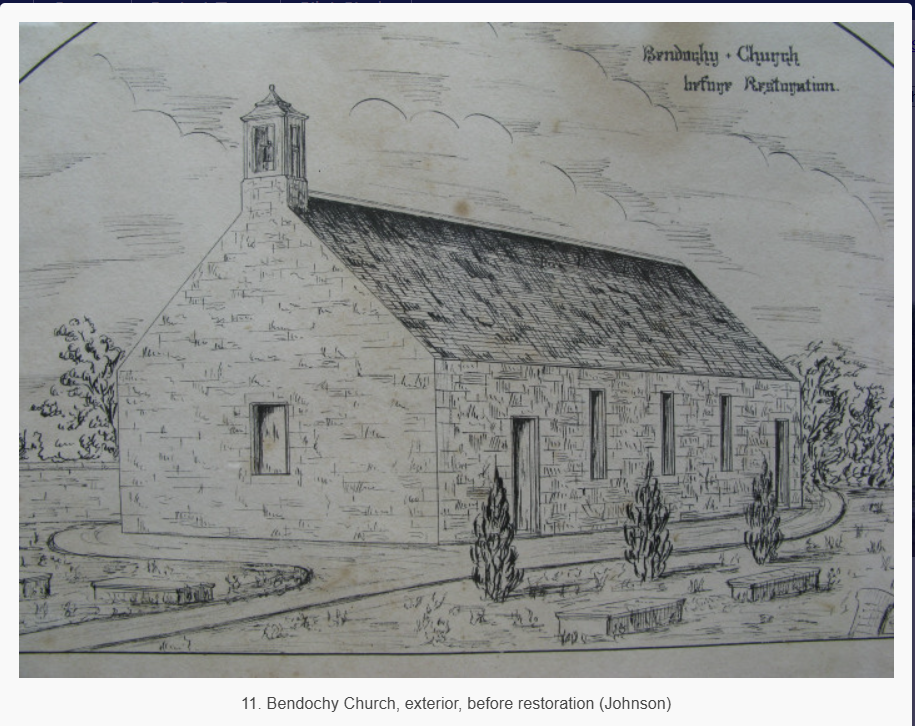

Bendochy Parish Church before the 1885 restoration.

This is the church where Duncan Robertson married Jean Angus in 1786, and where their son George was baptized in 1809.

Drawing by Johnson.

Two miles north of the market town of Cupar-Angus, beside the River Isla, stands one of the oldest ecclesiastical sites in Scotland. Bendochy Parish Church has been a place of worship for nine hundred years. The walls of the present building are seven centuries old, though the site was sacred even earlier, in the time of the Celtic Culdees.

Before the Reformation, Bendochy belonged to the Cistercian monks of Coupar Angus Abbey, just two miles away. The monks would ford the River Isla to visit the church and tend to Coupar Grange, the abbey's home farm. That ford was still in use within living memory.

For genealogists, what matters most about Bendochy is this: its parish registers begin in 1642—among the earliest in Scotland. When Duncan Robertson married Jean Angus in 1786, when their son George was baptized in 1809, when George married Margaret Paterson in 1838—all of these events were recorded in registers that survive to this day.

Bendochy Parish Records

1642

Parish Registers Begin

332

Parish Number

1855

Civil Registration Begins

Blairgowrie: Where the Highlands Meet the Lowlands

Blairgowrie sits at the northern edge of the beautiful valley of Strathmore, where the fertile lowlands give way to the rugged highlands. The River Ericht runs through the parish, formed by the union of the Ardle and the Black-water. The landscape is dramatic: in places the riverbanks rise two hundred feet above the water, and at Craigloch, perpendicular rock faces stretch seven hundred feet in length—"as smooth as if formed by the tool of the workman," wrote one nineteenth-century observer.

This was not gentle country. The River Ericht was rocky and uneven, prone to flooding in harvest season. Hawks nested in the cliffs at Craigloch. Salmon ran the Keith waterfall in such numbers that fishermen developed a unique method: hurling clay into the water at sunset to muddy the pools, then working their nets by torchlight.

But it was also prosperous country. The soil along the River Isla was deep, rich loam. Horses were reared here. Blairgowrie was a burgh of barony with its own baronial mansion, Newton-house, built in the style of a castle. By the time George Robertson was raising his family in the 1840s and 1850s, the town had nearly two thousand residents, with hundreds employed in agriculture and trade.

"About two miles north from Blair-gowrie the banks rise at least two hundred feet above the bed of the rivers; and on the west side are formed, for about seven hundred feet in length, and two hundred and twenty feet in height, of perpendicular rock, as smooth as if formed by the tool of the workman. The place where this phenomenon is to be seen is called Craigloch, where the traveller may be delighted with one of the most romantic scenes in North Britain."

— Topography of Great Britain, 1829

Understanding Scottish Records

Scottish genealogical research operates on a different system than English or American research. Understanding that system is essential to following the Robertson story—and to conducting your own Scottish research.

Before 1855: The Parish System

Before civil registration began on January 1, 1855, the only systematic records of births, marriages, and deaths in Scotland were kept by parish churches. The established church was the Church of Scotland, a Presbyterian denomination. Unlike in England, Scottish law never mandated that vital events be registered with the church—which means coverage is uneven.

Bendochy's registers are unusually complete, beginning in 1642. But even here there are gaps: no birth entries from December 1644 to January 1646, and mothers' names are sometimes omitted in the early 1700s. Other parishes have far worse gaps—or no surviving registers at all.

Non-Conformist churches—those outside the Church of Scotland—present additional challenges. Their records have often been lost or destroyed. And of course, some ancestors belonged to no church at all.

After 1855: Civil Registration

Scotland's civil registration system, which began in 1855, is a genealogist's dream. Death certificates routinely list both parents' names—including the mother's maiden name—providing a bridge back to the parish register era. Marriage certificates name parents of both bride and groom. The first year of registration, 1855, was especially detailed, including information that was later deemed unnecessary and dropped.

For the Robertson family, this means we can trace individuals who died after 1855 back to their parents in parish registers—connecting the Victorian era to the eighteenth century in a single document.

The Census

Scottish censuses were taken every ten years beginning in 1801, but only from 1841 onward do they enumerate individuals by name. The 1841 census captures Duncan Robertson at age 81, still working as a weaver in Bendochy. The 1851, 1861, and 1871 censuses show his son George's family growing in Blairgowrie. These snapshots, taken at ten-year intervals, form the backbone of our family reconstruction.

Where to Find Scottish Records

ScotlandsPeople — The official government website. Civil records from 1855, parish registers, census records, wills, and more. Pay-per-view, but reasonable rates and exceptionally comprehensive.

FamilySearch — Free access to many Scottish parish registers and census records (1841–1891). Microfilms available at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City.

Ancestry and FindMyPast — Additional indexed collections, sometimes with different transcriptions that can help decipher difficult handwriting.

A Tangible Connection

Part of my process of researching ancestors is that when I discover their location of origin, I search for some type of historical map or artifact or art from that area as a tangible connection to them. Once we pinpointed Bendochy, Perthshire as the Robertson homeland, I went searching—and discovered something extraordinary.

A Perthshire paperweight—a tangible connection to the homeland of our Robertson ancestors.

Perthshire Paperweights. I had never seen anything like them—intricate patterns of colored glass, millefiori canes arranged in precise geometric designs, encased in crystal-clear domes. And they came from the very county where George Robertson was born, where his father Duncan wove cloth, where generations of our family lived before the great emigration.

The tradition began in 1922 when Salvador Ysart, a Spanish glassmaker, moved his family to Crieff—just 25 miles from Blairgowrie. Perthshire Paperweights was founded there in 1968, producing exquisite handcrafted weights until 2002. I purchased three: one for my mother, one for myself, and one for my daughter. Three generations of women, connected to six generations of Robertson ancestors, through a piece of Scottish glass art.

My mother particularly enjoyed learning how they were created—the painstaking process of forming colored glass canes, arranging them in intricate patterns, encasing them in layers of molten crystal. These small globes became more than decorative objects. They became conversation starters, teaching moments, tangible proof that our ancestors came from a real place with real traditions.

Read the full story: Perthshire Paperweights — A Genealogist's Discovery →

The Family We'll Follow

In the episodes that follow, we will trace six generations of one Robertson family:

Duncan Robertson, a weaver in Bendochy, married Jean Angus in 1786. They raised their children in the townland of Myreridges, and Duncan was still working his loom at age 81 when the census taker came calling in 1841.

Their youngest son, George Robertson, became a mason in Blairgowrie. He married Margaret Paterson in 1838 and raised ten children. In 1872, at age 63, he crossed the Atlantic to join his children in America. He survived five days.

George's son David Paterson Robertson was the pioneer—the first to emigrate, in 1869. He became a stone cutter in Brooklyn, raised eleven children, and then, newly widowed at 63, reinvented himself as a game trapper in Georgia. In 1910, he vanished into the swamps. His boat was found. His body never was.

David's son Joseph Robertson searched Georgia for his missing father. He married Mary Agnes Kenny—daughter of a Brooklyn mat maker—and died of a stroke in 1924. His wife followed twelve days later. Their children were orphaned.

Their eldest daughter, Lillian Josephine Robertson, was eighteen years old when she became an orphan. She married a Brooklyn carpenter, returned to New Jersey, and built a family. By her fiftieth wedding anniversary in 1978, she was surrounded by nineteen grandchildren.

This is the story we'll tell. But first, we needed to understand the land they left.

Six Generations

Duncan Robertson • Weaver, Bendochy (c.1760–?)

↓

George Robertson • Mason, Blairgowrie (1809–1872)

↓

David Paterson Robertson • Stone Cutter, Brooklyn (1842–c.1910)

↓

Joseph Robertson • Marine Industry, Brooklyn (1884–1924)

↓

Lillian Josephine Robertson • The Orphan (1905–1991)

↓

Barbara Ann O'Brien • Keeper of Stories (1935–2022)

Continue the Story

Scattered Stones: Series Overview

Episode 1: Roots in Perthshire → — The marriage of Duncan Robertson and Jean Angus

Storyline Genealogy

From Research to Story

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY