Quimper Pottery: A Genealogist's Discovery

Quimper Pottery

Genealogical research fills notebooks with names and dates, census entries and vital records. But sometimes, in the midst of all that documentation, you discover something that makes the past suddenly, tangibly present.

I have always been drawn to Quimper pottery. The hand-painted Breton figures, the vibrant blues and yellows, the graceful curves of pitchers and vases—there was something about them that felt familiar, though I couldn't say why. I'd see a piece in an antique shop and pause, feeling that pull collectors know well: the one that says this belongs with you.

Now I know why.

The Discovery

While researching my French-Canadian ancestry, I traced the Tranchemontagne line back to its origin—to an immigrant named Nicolas Sulière who crossed the Atlantic to New France in the late 17th century. His 1740 burial record preserved the one detail that changed everything: he was born in Quimper, Brittany, France.

Read Nicolas Sulière's Story →Quimper—pronounced "kem-pair"—is more than a town. It is a people, a place, and a pottery tradition stretching back more than three centuries. The name itself comes from the Breton word kemper, meaning "confluence," for the town sits where the Odet and Steir rivers meet. That confluence of waters made it an ideal place for pottery production, and by 1690, the first faïencerie was established there.

The Town, The People, The Pottery

Nicolas Sulière was born in Quimper around 1665—just as the pottery tradition was taking root. The town's abundant clay deposits, access to waterways for transportation, and skilled artisan community created the conditions for what would become one of France's most distinctive ceramic traditions.

The pottery made there is called faïence—tin-glazed earthenware, hand-painted with scenes of Breton life. The technique is demanding, requiring both technical precision and artistic skill. I've heard it compared to puff pastry: layers of complexity that must be mastered before anything beautiful emerges.

"The making of faïence is an art. Especially in the early days, prior to the introduction of more modern methods, when both the technical and artistic skills necessary to make a piece of faïence were quite daunting."

— oldquimper.com

By the late nineteenth century, three major factories operated in Quimper: the Porquier factory, the Grande Maison (de la Hubaudière), and the Faïencerie d'Art Breton owned by Jules Henriot. Their pieces—decorated with "petit Breton" figures in traditional costume, florals, and distinctive blue-and-yellow borders—became prized throughout France and beyond.

Why It Calls to You

There's a theory among collectors that we're sometimes drawn to objects connected to our heritage before we know the connection exists. The Celtic resonance of Breton culture—its ties to Cornwall, Ireland, Scotland, Wales—speaks to something in people of those ancestries. The folk motifs, the traditional costumes, the scenes of rural life: they carry echoes of a world our ancestors knew.

I didn't know my ancestor was from Quimper when I first felt that pull toward its pottery. But perhaps some part of me recognized it anyway.

The Collection Begins

What to Look For

I'm drawn particularly to pitchers and vases—the graceful forms, the way they catch light, the sense of something made to be used and loved. (This mirrors my uranium glass collection, which is another story entirely.) For those beginning to explore Quimper pottery, here's what I've learned:

Identifying Authentic Quimper

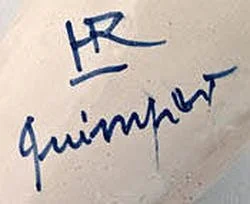

- Maker's marks: Look for "HB," "Henriot," "HR," or "Quimper France" on the base. The mark helps date the piece and identify the factory.

- Hand-painted details: Authentic pieces show the individual brushwork—slight variations that prove human hands created them.

- Breton motifs: Traditional figures in costume, florals, birds, and the distinctive blue-and-yellow palette.

- Condition: Minor crazing is common in vintage pieces, but chips and cracks reduce value significantly.

- The "Golden Age": Pre-World War II pieces (especially late 19th/early 20th century) are most prized by collectors.

Holding History

When I hold a piece of Quimper pottery now, I'm holding more than an antique. I'm holding something made in the town where my ancestor was born—where he was baptized, where he learned whatever trade or skill he carried across the Atlantic to a new world. The same rivers that allowed pottery production also shaped his earliest years.

Nicolas Sulière left Quimper sometime before 1691. He carried with him the name "Tranchemontagne"—the one who cuts mountains—and whatever else a young man brings when he leaves everything familiar behind. He couldn't have known that three hundred years later, someone would trace his steps backward and find, in the pottery of his hometown, a tangible connection to a life otherwise known only through faded ink in parish registers.

Genealogical research is, at its heart, an act of recovery. We recover names. We recover dates. We recover, if we're lucky, some sense of who these people were and how they lived.

But sometimes—in a piece of Scottish glass, in a shard of French pottery—we recover something we can touch. Something that says: this place was real. This person was real. And now, in some small way, they are here with you.

I don't know yet how large this collection will grow. A pitcher, perhaps, for each generation. A vase for each discovery. Or maybe just the pieces that call to me, the way they always have, now that I understand why.

The town. The people. The pottery.

And an ancestor I never knew, who has been with me all along.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY