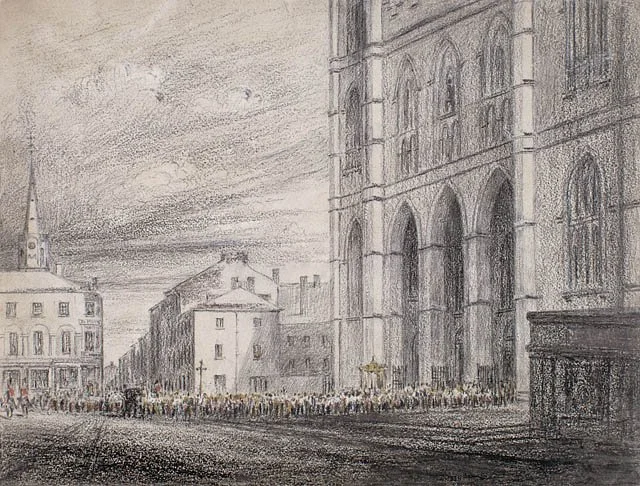

Notre-Dame Basilica : Montreal’s Mother Church

Place d’Armes, Old Montreal, Quebec

Notre-Dame Basilica

The largest church in North America when the Hamall family arrived as Famine refugees in 1850. Within these walls, they buried a child and a father, witnessed a widow's remarriage, and baptized the half-brother whose identity would remain a mystery for 170 years.

The Hamall-McMahon-Thornton Family at Notre-Dame

Daughter of Henry & Mary McMahon

Survived the Famine, died in Montreal

Son of Henry Hamall (journalier)

& Mary McMahon

Daughter of Henry Hamell

& Mary McMahon

Journalier (day laborer)

Left widow with 3 children

married Patrick Thornton

Creating the blended family

Son of Patrick Thornton

& Mary McMahon

KEY DOCUMENT

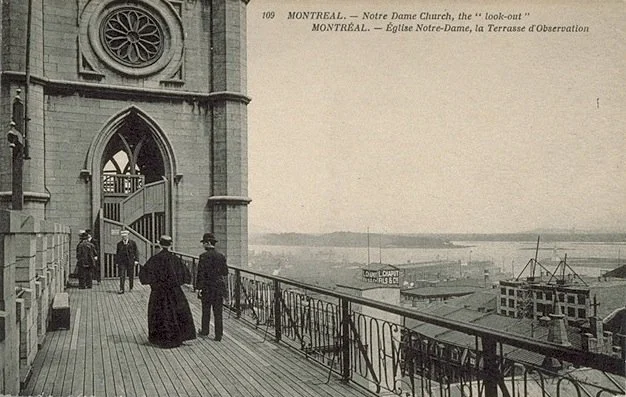

Notre-Dame Basilica and Place d'Armes, Montreal—the church where the Hamall family worshipped after emigrating from Ireland during the Great Famine. Postcard from BAnQ Digital Collection.

When Henry Hamall and Mary McMahon arrived in Montreal around 1850 with their young children—refugees from the Great Famine in County Monaghan, Ireland—Notre-Dame Basilica was the largest church in North America. Its twin Gothic towers dominated the skyline of a city still rebuilding after the devastating fires of 1849. For Irish Catholic immigrants, this magnificent church offered both spiritual refuge and practical community in a new and uncertain world.

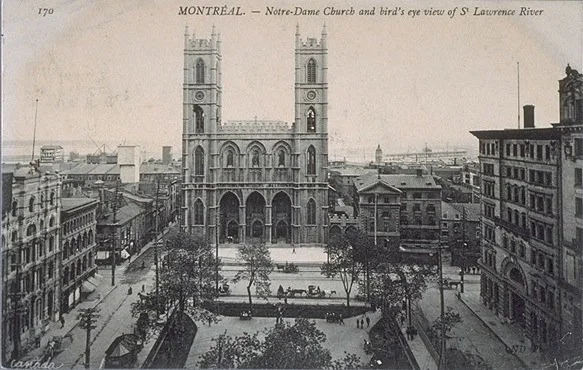

The Hamall family's story at Notre-Dame spans just six years, from 1851 to 1856, but those years encompass the full arc of immigrant experience: hope and heartbreak, death and remarriage, the dissolution of one family and the creation of another. The parish registers of Notre-Dame document each chapter—and one baptismal record from January 1856 would ultimately provide the key to solving a genealogical mystery that persisted for 170 years.

Montreal's Mother Church

Notre-Dame Basilica stands at the heart of Old Montreal, facing Place d'Armes where a statue of Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve commemorates the city's founding in 1642. The current building—designed by Irish-American architect James O'Donnell in the Gothic Revival style—was constructed between 1824 and 1829, replacing an earlier church that had become too small for Montreal's growing Catholic population.

Architect James O'Donnell designed Notre-Dame in the Gothic Revival style then flourishing in Europe and America, inspired by Notre-Dame de Paris and the Church of Saint-Sulpice. At 216 feet long and capable of holding 8,000-10,000 worshippers, it was the largest church in North America until St. Patrick's Cathedral opened in New York in 1879. The twin towers—La Persévérance (1841) and La Tempérance (1843)—house the 10,900 kg bell "Jean-Baptiste" and a ten-bell carillon. O'Donnell, a Protestant, converted to Catholicism on his deathbed and is buried in the church's crypt.

The Irish at Notre-Dame

Before the establishment of dedicated Irish parishes—St. Patrick's in 1847 and St. Ann's in 1854—Notre-Dame served as the primary church for English-speaking Catholics in Montreal, including the rapidly growing Irish immigrant community. During the 1840s and 1850s, Irish parishioners at Notre-Dame actually outnumbered the French Canadians.

The summer of 1847 was particularly catastrophic. Tens of thousands of Famine refugees arrived in Montreal carrying typhus—"ship fever"—leading to an epidemic that killed thousands. The Black Rock monument near Victoria Bridge commemorates the 6,000 Irish immigrants who died that summer. Those who survived, like the Hamall family who arrived around 1850, found a community struggling to accommodate the influx but united in faith.

"The Irish were a 'double minority'—a religious minority among English Protestants and a linguistic minority among French Catholics—but their shared Catholic faith helped them bridge the gap with French Canadians."

By 1867, the Irish had established their own network of "national parishes"—St. Patrick's, St. Ann's in Griffintown, St. Bridget's, St. Gabriel's, and St. Anthony of Padua—allowing them to worship in English while maintaining their distinct cultural identity. But in the early 1850s, when the Hamall family arrived, Notre-Dame remained the center of Irish Catholic life in Montreal.

The Hamall Family at Notre-Dame

The parish registers of Notre-Dame document the Hamall family's brief but significant presence in Montreal. These records—baptisms, burials, and one marriage—tell a story of loss, resilience, and family reconstitution that would echo across generations.

Mary Hamall

Daughter of Henry Hamall and Mary McMahon. Died age approximately 4 years. Born in Ireland.

Michael Hamall

"Born about a year ago" (c. 1850). Son of Henry Hamall (journalier/day laborer) and Mary McMahon. Sponsor: Sarah McMahon (likely Mary's relative).

Mary Ann Hamall

Daughter of Henry Hamell and Mary McMahon. Godfather: Owen Duffy. Godmother: Ann Brennan.

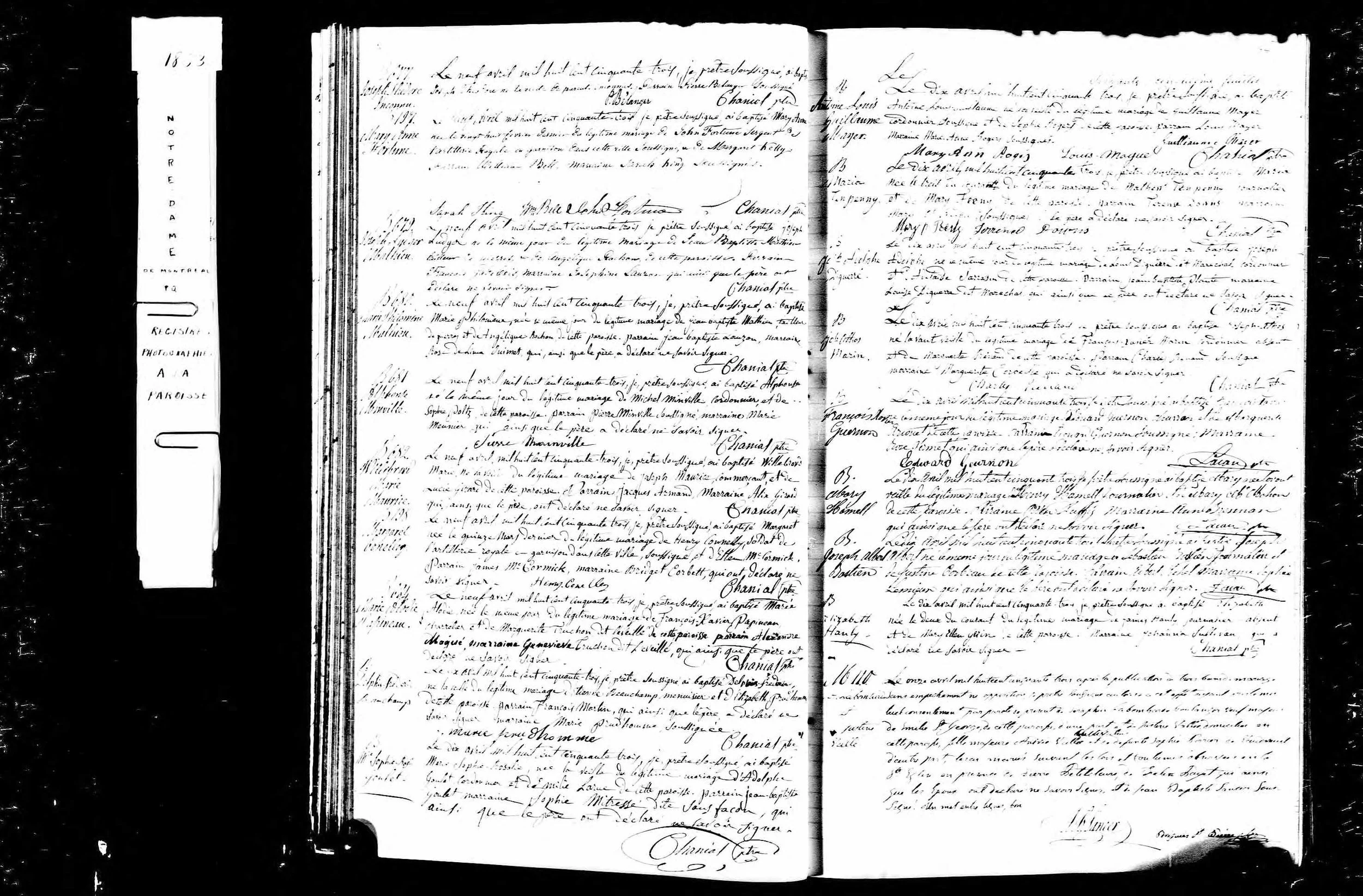

Baptism register entry for Mary Ann Hamall, April 10, 1853, showing parents "Henry Hamell and Mary McMahon"—contemporary documentation of Owen Hamall's parents' names.

Henry Hamall

Journalier (day laborer). Deceased aged approximately 37 years (born c. 1817).

Burial register showing Henry Hamall, journalier, deceased aged approximately 37, buried May 1854. His death left Mary McMahon a widow with three young children.

The Key Document

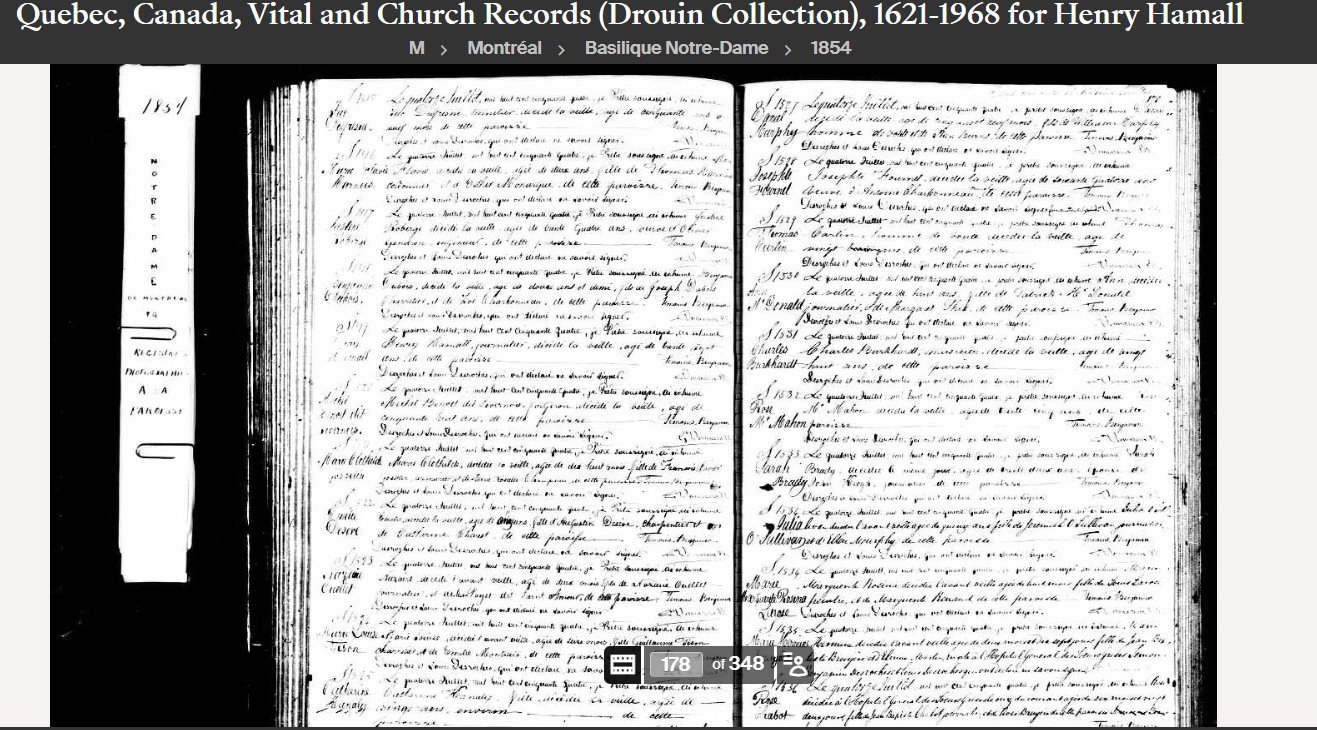

For six years—from September 2018 to March 2024—the identity of "Hammil, Thornton" in Owen Hamall's 1880 Chicago census household remained an unsolved mystery. The census listed this person as Owen's "brother," age 24, born in Canada. But why would Owen's brother have a different surname? Traditional surname searches failed because the census enumerator had recorded "Hammil" as the surname with "Thornton" as a given name or separate notation.

The breakthrough came through a baptism record at Chicago's Church of the Holy Family, which showed reciprocal sponsorship between Owen and a man named William Thornton in 1883. This proved a close family relationship—but it didn't explain the different surnames. The answer lay in Montreal, in the parish registers of Notre-Dame.

William Thornton

Son of Patrick Thornton and Mary McMahon of this parish. Born 20 January 1856.

The key document: William Thornton's baptism record, January 24, 1856, naming parents Patrick Thornton and Mary McMahon. This record—combined with the 1855 marriage and earlier Hamall family records—proved that William Thornton was Owen Hamall's half-brother.

The Evidence Chain

1. 1841: Mary McMahon married Henry Hamall in Donaghmoyne, Ireland.

2. 1851-53: Notre-Dame records show children of Henry Hamall and Mary McMahon.

3. 1854: Henry Hamall dies in Montreal, leaving Mary a widow.

4. 1855: Mary McMahon (explicitly "widow of Henry Hamall") marries Patrick Thornton.

5. 1856: William Thornton baptized, son of Patrick Thornton and Mary McMahon.

6. 1880: William Thornton (age 24, born Canada) lives with Owen Hamall as "brother."

Therefore: Owen Hamall and William Thornton shared the same mother (Mary McMahon) but had different fathers (Henry Hamall vs. Patrick Thornton) = half-brothers.

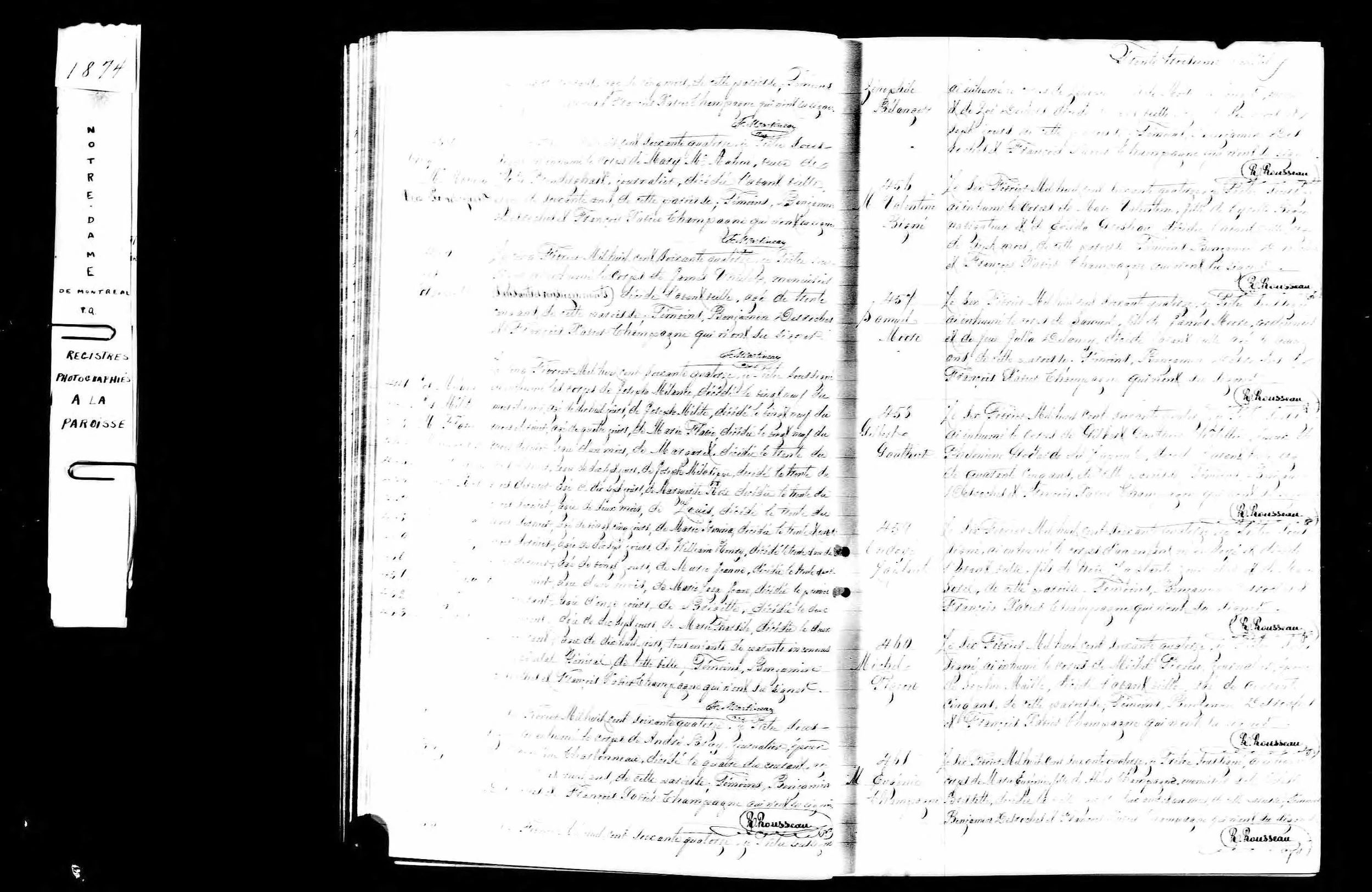

The End of an Era

Mary McMahon—who had survived the Famine in Ireland, emigrated to Canada, buried a husband and a child, remarried, and raised children from both marriages—died in Montreal on September 19, 1874. Her burial record at Notre-Dame identifies her as "Mary McMahon, widow of the late Henry Hammel"—she was identified by her first husband's name even twenty years after his death.

Death record for Mary McMahon, September 19, 1874. The record identifies her as "widow of the late Henry Hammel"—her first husband's name, even twenty years after his death.

By 1874, Owen Hamall was approximately 27 years old. Both of his parents had died before his marriage to Catherine Griffith in Chicago five years later. The Montreal chapter of the family story was closed, but the ties between the half-brothers—Owen Hamall and William Thornton—would continue across the border, documented in Chicago census records and baptismal registers for decades to come.

The Basilica Today

Notre-Dame de Montréal Church (Basilica). Photo by Georges Delfosse, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Notre-Dame Basilica was raised to the rank of minor basilica by Pope John Paul II on April 21, 1982, and designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1989. Today it welcomes over a million visitors annually, drawn by its architectural magnificence and rich history. The interior—redecorated under Victor Bourgeau from 1872-1880 in colors inspired by Sainte-Chapelle in Paris—features the famous Casavant organ and the 14-meter-high pulpit sculpted by Louis-Philippe Hébert.

For genealogists, the parish registers of Notre-Dame remain an invaluable resource. Available through the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) and FamilySearch, these records document the lives of generations of Montreal families—including the Famine refugees who, like the Hamalls, found both sorrow and new beginnings within these walls.

Notre-Dame parish registers (1642-present) are available through the Drouin Collection at Ancestry.com and through FamilySearch's "Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records" collection. The original registers are held by the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ). Records from the 1850s—including all Hamall family documents referenced in this article—are fully digitized and searchable online.

Document Gallery

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY