Tranchemontagne: Jacque Souliere

Jacques Souliere

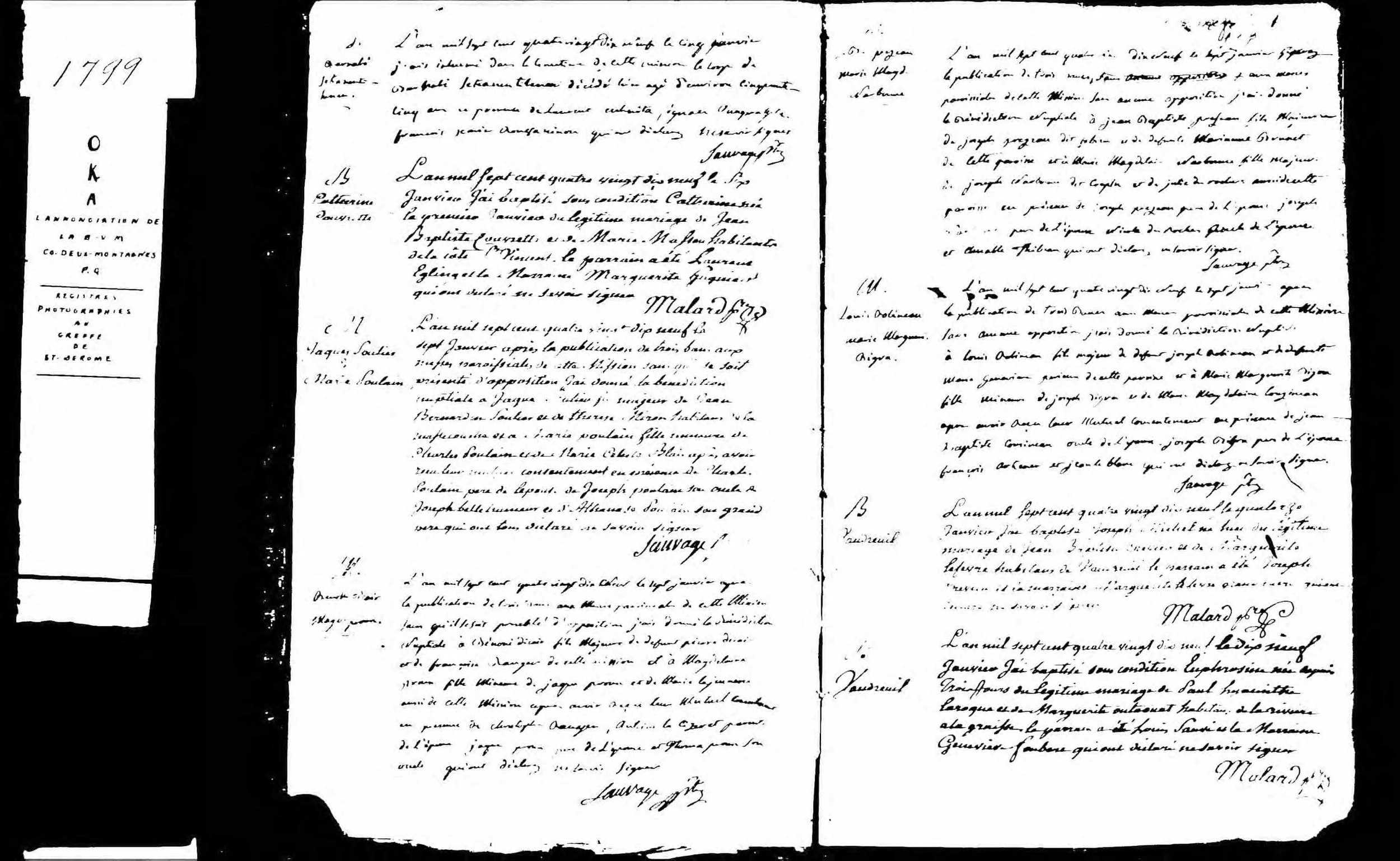

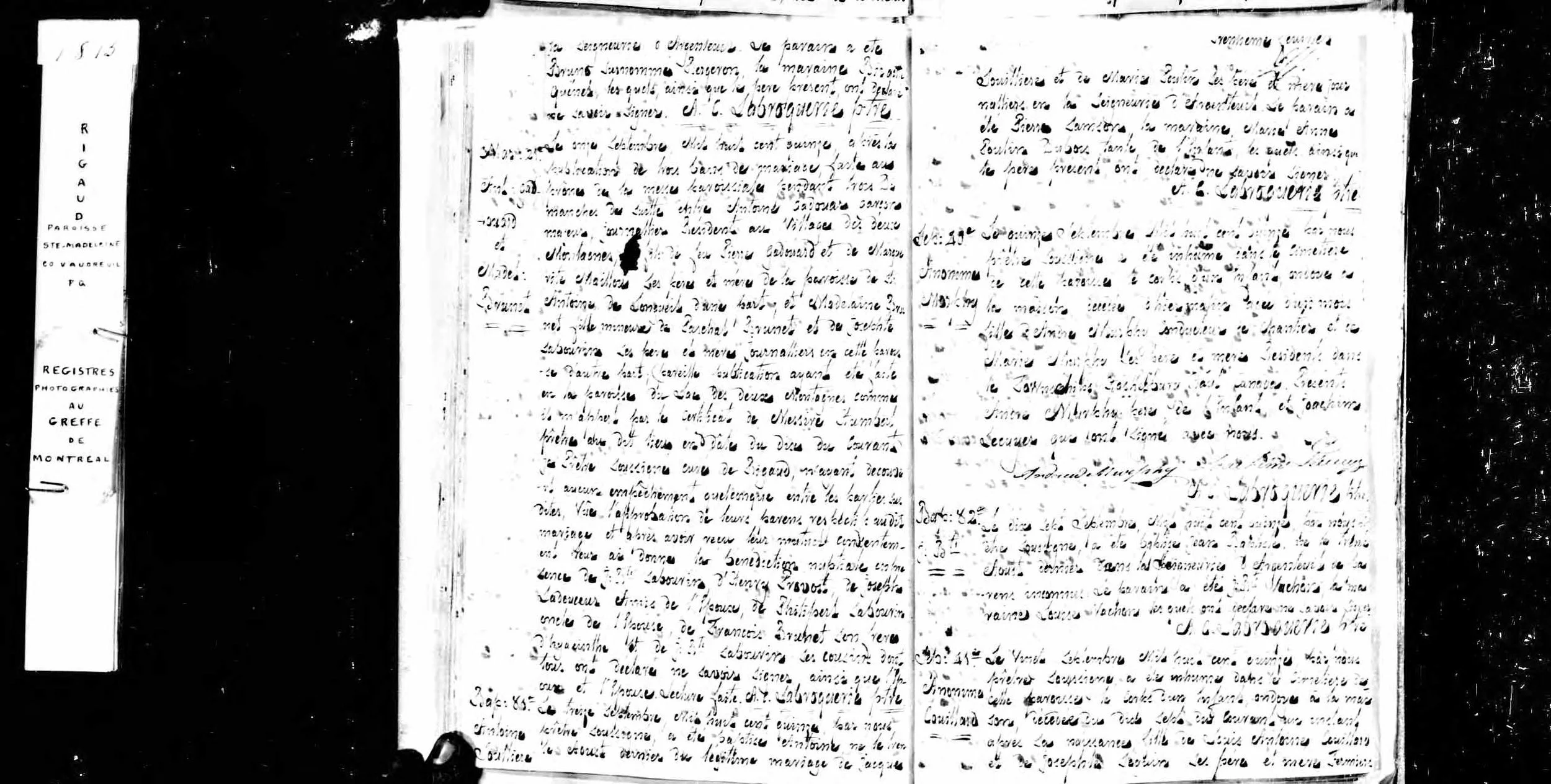

On January 7, 1799, in the Mission church at Oka, a thirty-year-old farmer from L'Assomption married a seventeen-year-old girl from Pierrefonds. The priest recorded him as "Jacques, fils majeur de Jean Bernard dit Soulier de Theron." She was "Marie Poulain, fille mineure de Charles Poulain et de Marie Celest Blaincoye." Neither could sign their names. Neither knew that their union would produce ten children, survive unimaginable loss, and anchor a family line that would stretch across two centuries and three countries.

Jacques Souliere was born on June 25, 1768, in L'Assomption, Quebec—the second of fifteen children born to Jean Bernard Suliere Bernardin and Marie Thérèse Migneron Rivière. His father's family had been in New France for generations, part of the web of habitants who farmed the narrow strips of land along the St. Lawrence. The name itself tells a story: "Suliere dit Bernardin"—a dit name, the kind French-Canadians used to distinguish branches of large families. By the time Jacques was baptized, the British had controlled Quebec for nearly a decade, but life in the parishes went on as it always had: in French, in the church, measured by planting and harvest and the feast days of saints.

A Marriage at Oka

By 1799, Jacques had moved west from L'Assomption to the Seigneurie d'Argenteuil, the frontier country north of Montreal where land was still available for young men willing to work it. Marie Elisabeth Poulin came from Pierrefonds, daughter of Charles Poulin and Marie Céleste Blais. She was barely seventeen when she stood before the priest at Oka—the ancient Sulpician mission where Mohawk, Algonquin, and French-Canadian Catholics had worshipped together for over a century.

The marriage record lists the witnesses: Charles Poulain, father of the bride. Joseph Poulain, her uncle. Joseph Belle Isneaux. And the bride's grandfather, whose name the priest recorded but who, like everyone else present, declared he could not sign. They were all farmers, all illiterate, all part of the same tight-knit world of rural Quebec where families intermarried, where everyone knew everyone, where land and faith and family were the only things that mattered.

Building a Family in Rigaud

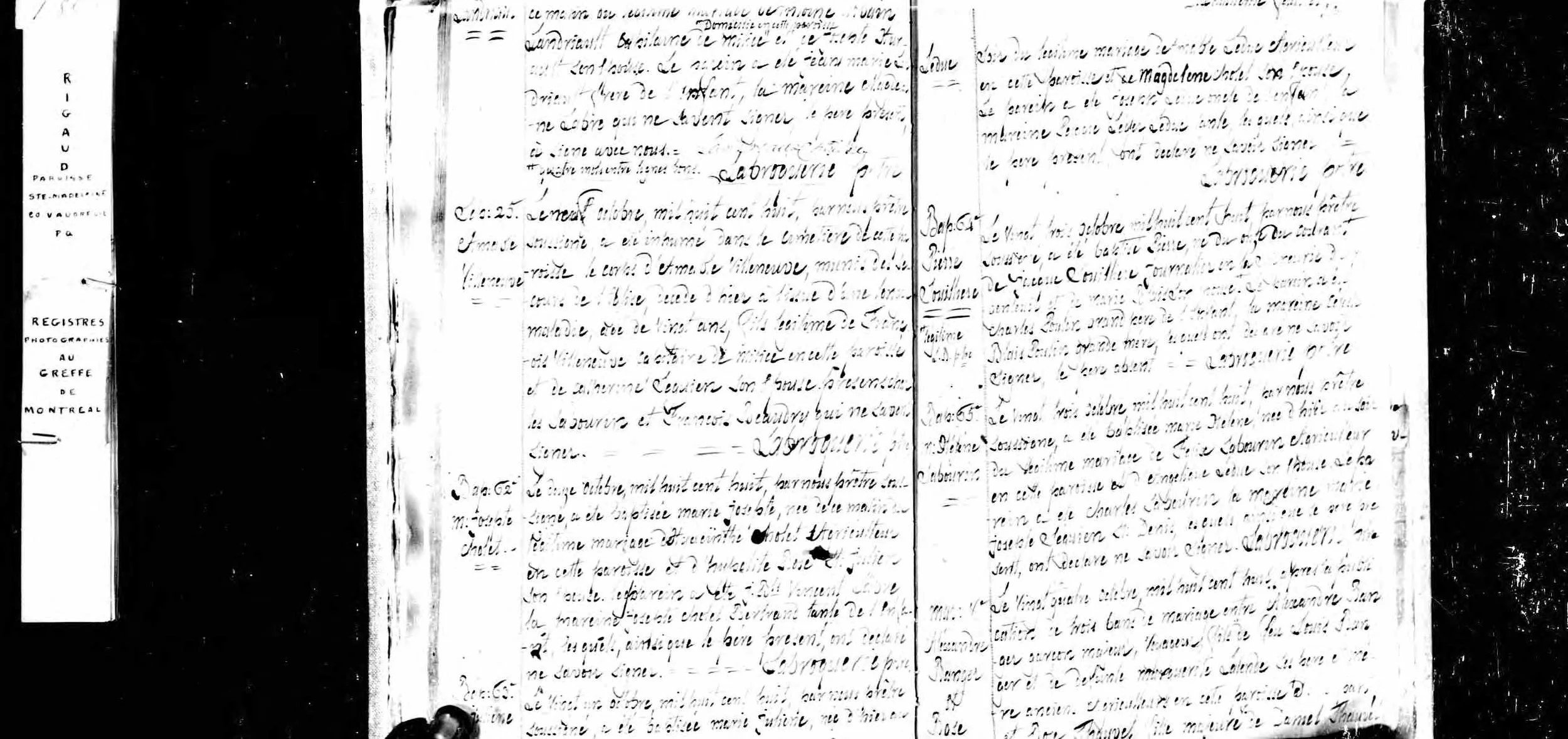

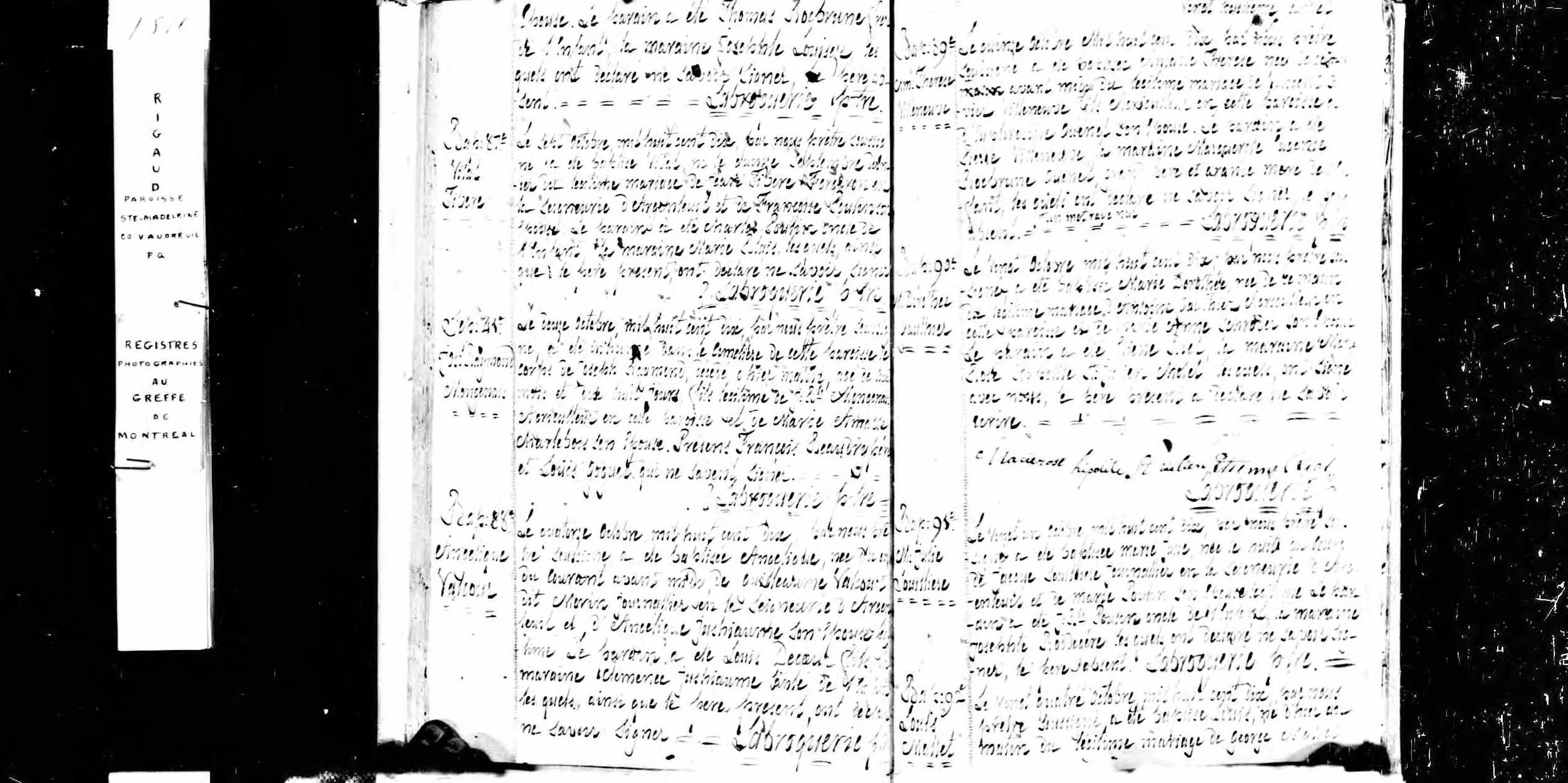

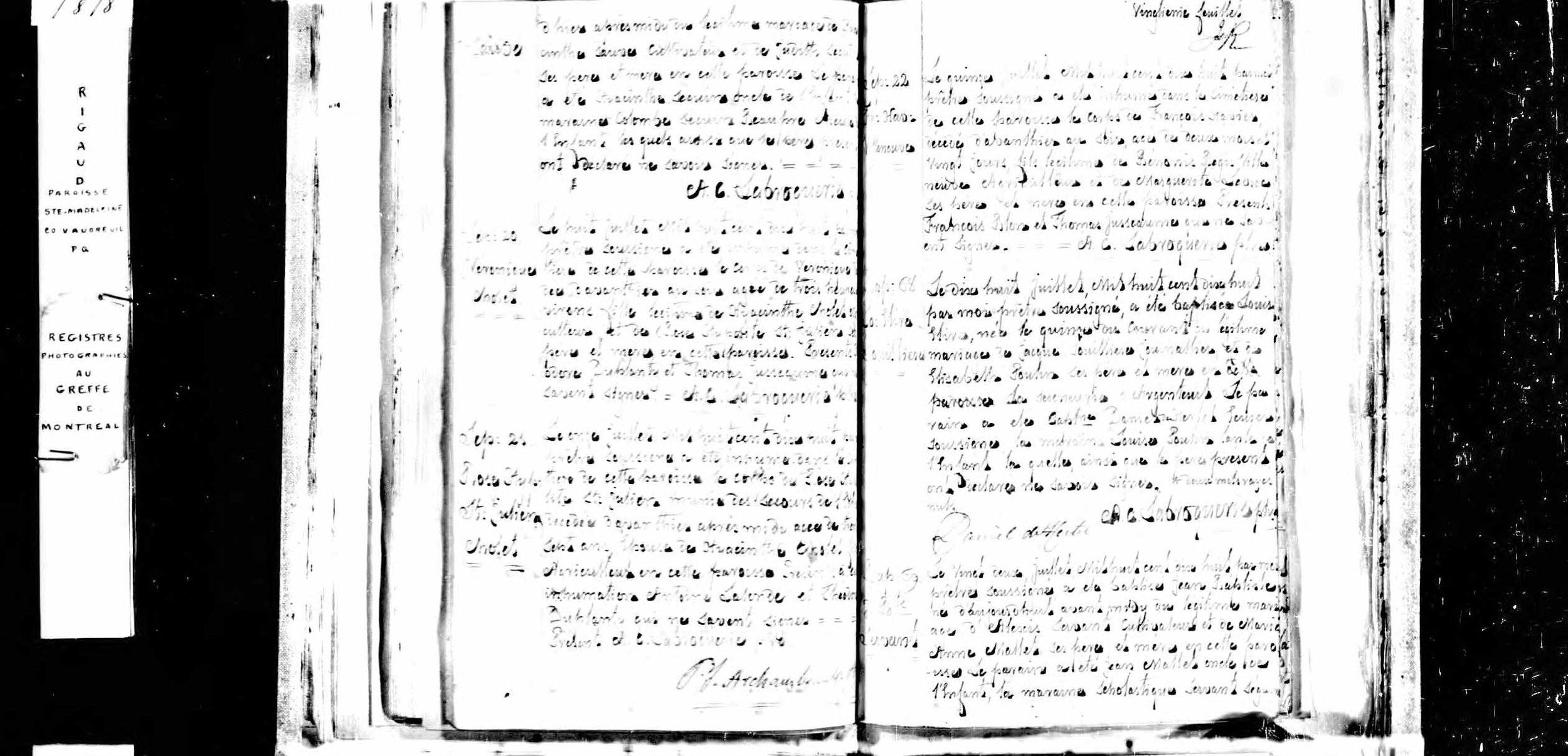

Jacques and Elisabeth settled in Rigaud, in the Seigneurie d'Argenteuil, where Jacques worked the land as a "cultivateur"—a farmer. Their first son, Jean Baptiste, was born in August 1801 at St-Benoît. Then François in 1804. Then Janvier—named for the month of his parents' wedding—in January 1806. The baptism records show the pattern of their lives: Jacques listed as "agriculteur" or "cultivateur," the godparents drawn from Elisabeth's family (the Poulins appear again and again), the same priest signing entry after entry.

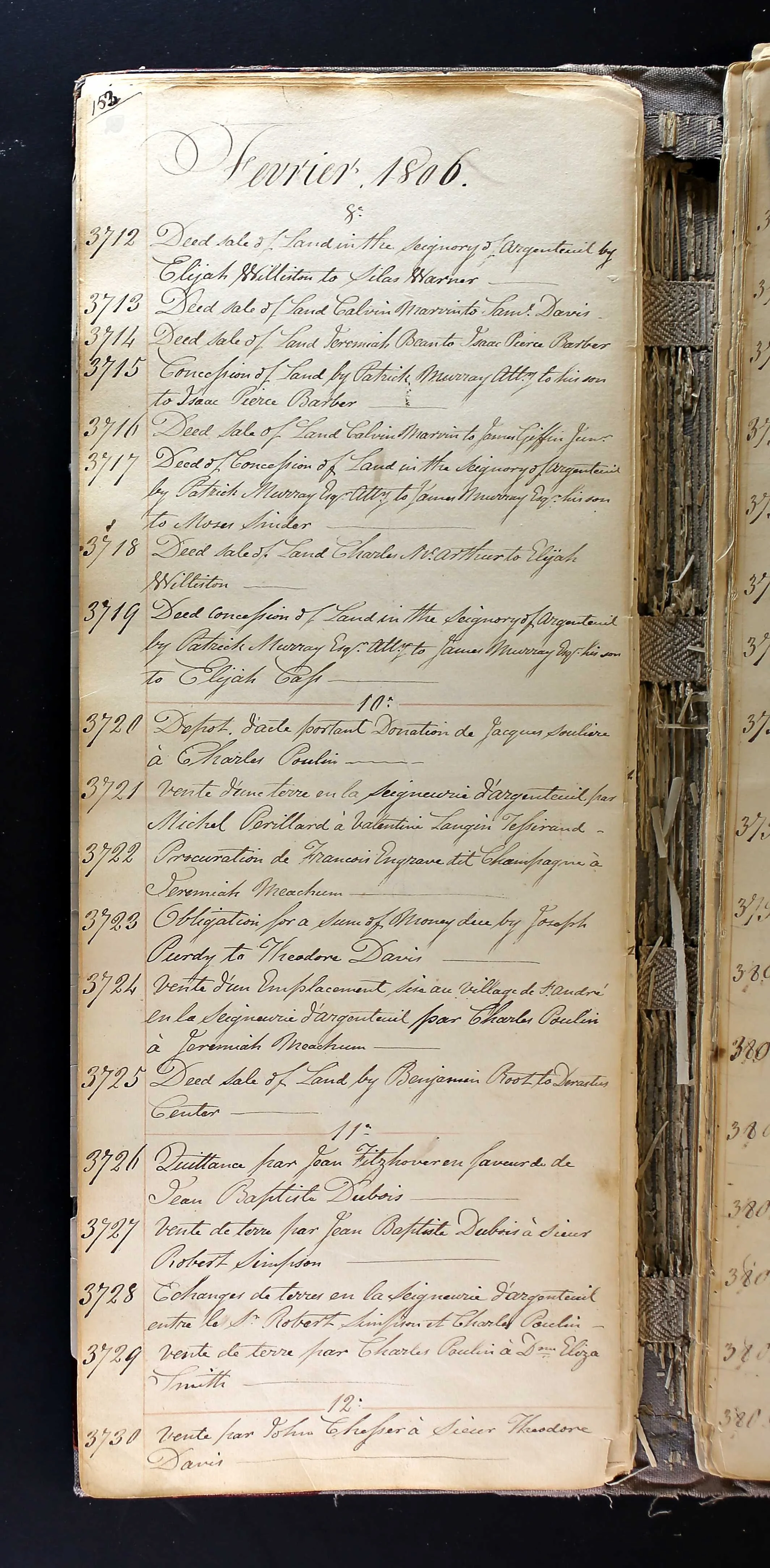

A curious document from February 1806 hints at the family's circumstances: a notarial record of a "Donation de Jacques Souliere à Charles Poulin." Jacques was transferring something—land? property? rights?—to his father-in-law. The document sits in the notarial archives, a reminder that these illiterate farmers lived within a sophisticated legal system that recorded their obligations and transactions in careful handwriting.

More children came. Pierre in 1808. Marie Julie in 1810. Another Jacques in 1812—a son named for his father. By 1813, the household held six children under twelve, two parents in their forties, and whatever extended family helped work the land. It was a full house, a growing family, a future taking shape.

The Year of Loss

And then came 1814.

Something happened in early 1814 that brought the Souliere family to Montreal. Perhaps it was work. Perhaps it was illness—though the records don't say. What the records do say is devastating.

Spring 1814 — Notre-Dame de Montréal

Three children dead in two months. The burial registers of Notre-Dame de Montréal record each one with brutal efficiency: name, age, parents, date. Little Jacques first, not yet two. Then Pierre, who had lived five years. Then Marie Julie, three years old. The causes of death aren't recorded—they rarely were—but the timing suggests epidemic disease, perhaps typhus or typhoid, perhaps measles or whooping cough. In an era before antibiotics, before vaccines, before germ theory itself was understood, childhood illness swept through families like fire.

Jacques and Elisabeth buried their children in the cemetery of Notre-Dame. Then they returned to Rigaud and did the only thing people in their world could do: they kept living.

The Years After

Antoine was born in August 1815, seventeen months after Marie Julie's death. Louis followed in July 1818. A child recorded only as "Infant" was born on December 26, 1820, and died three days later—another loss, barely noted. Marie Archange arrived in June 1822. And finally Michel, on the last day of 1825, when Jacques was fifty-seven and Elisabeth forty-four.

Ten children in twenty-four years. Three dead before they reached school age. One dead within days of birth. Six who survived to adulthood, married, had children of their own.

The Children of Jacques & Elisabeth

The Man Who Disappeared

And then Jacques Souliere vanishes from the historical record.

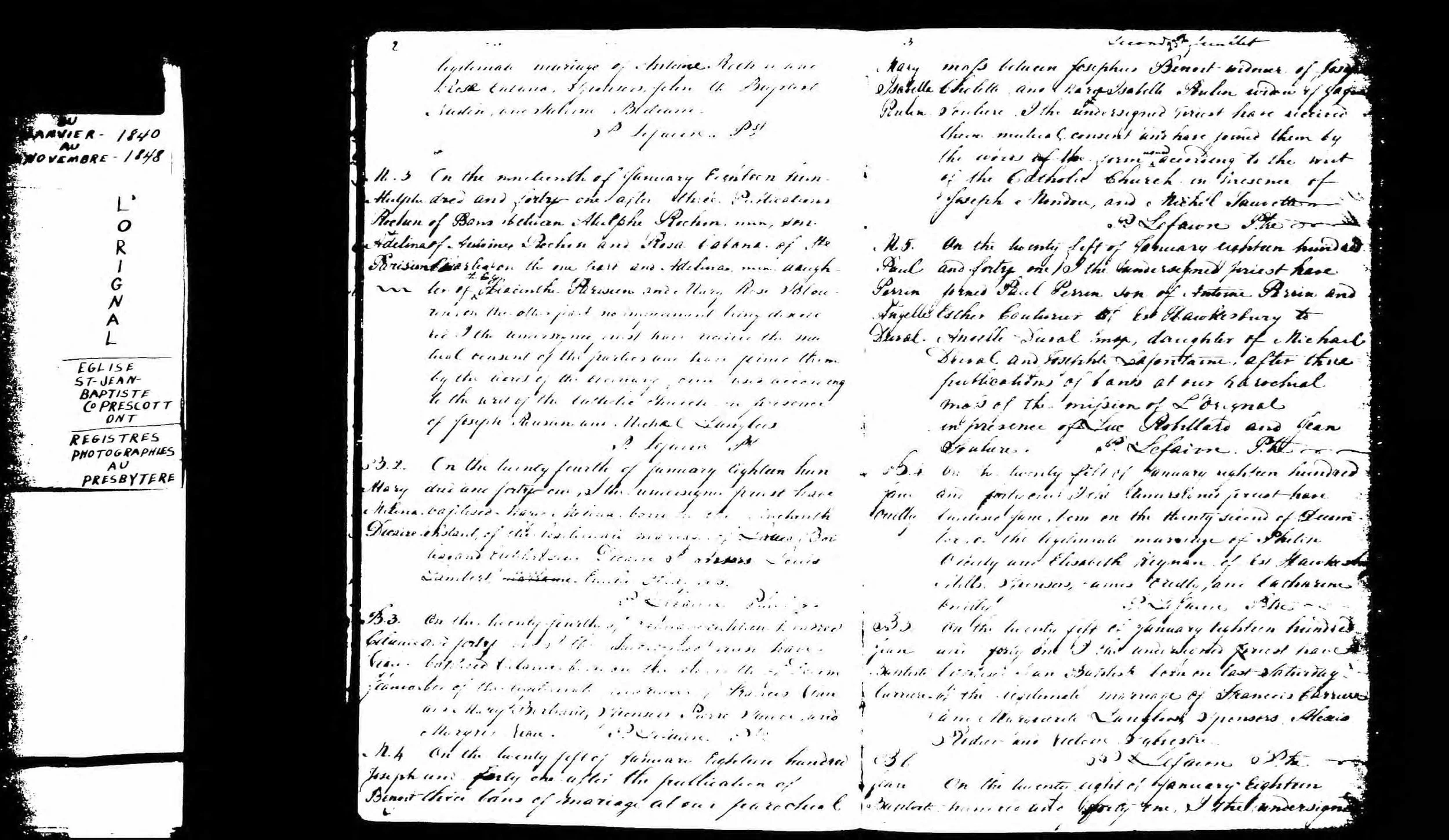

No death certificate has been found. No burial record. No obituary, no estate settlement, no mention in the later records of his children. We know only this: on January 21, 1841, at L'Orignal in Prescott County, Ontario, "Marie Elisabeth Poulin, veuve de Jacques Souliere" married Joseph Vaillancourt Benoit. Widow. She was Jacques's widow.

He must have died sometime between Michel's birth in December 1825 and Elisabeth's remarriage in January 1841—a gap of fifteen years. Perhaps he died in the cholera epidemic of 1832, which devastated Quebec. Perhaps he died of the ordinary causes that took farmers in their sixties: accident, illness, the accumulated wear of a life spent working the land. Perhaps his burial was recorded in a register that has since been lost, or in a parish whose records haven't been fully indexed.

What we know for certain is that Elisabeth survived him. She remarried. She moved to L'Orignal, across the Ottawa River in Ontario, where her sons Janvier and Michel had already settled. She lived another eleven years, dying on August 14, 1852, at St-André-Est in Argenteuil, at the age of seventy-one. Her burial record names her as "Marie Elisabeth Poulin, épouse de Joseph Benoit"—wife of her second husband. But it was as Jacques Souliere's widow that she had raised their surviving children, that she had watched them marry and have children of their own, that she had carried the family forward into the next generation.

What He Left Behind

Jacques Souliere left no letters, no diaries, no photographs. He left no signature—he could not write his name. What he left were children, and through them, grandchildren and great-grandchildren who would scatter across North America: to Ottawa, to Montreal, to Chicago, to Miami.

His son Janvier would marry three times and father nineteen children. His granddaughter Marie Louise would live to be ninety-one, would remember stories of the old country, would pass them down to a great-great-grandson who would fish with her in Miami when she was ancient and he was young. His great-great-great-granddaughter would find these records two centuries later and piece together what it meant to be Jacques Souliere: a farmer, a father, a man who buried three children in two months and somehow kept going.

In the end, that is his legacy. Not the land he farmed, which passed to other hands long ago. Not the house he built, which is gone. But the family line that stretches from L'Assomption in 1768 to the present day—seven generations of Soulieres and their descendants, all of them carrying forward the genetic inheritance and the family stories of a man who could not sign his own name but whose life, recorded in the careful handwriting of priests and notaries, still speaks to us across the centuries.

Document Gallery

Primary sources documenting the life of Jacques Souliere and Marie Elisabeth Poulin. Click any image to enlarge.

Storyline Genealogy

From Research to Story

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY