Scattered Stones: The Brooklyn Robertsons

The Brooklyn Robertsons

A Widow Holds the Family Together. Then 1892 Takes Everything.

"Robertson, Margaret, wid. Geo. 119 Hamilton av" — Brooklyn City Directory, 1874

For twenty years, Margaret Paterson Robertson was defined by loss. The Brooklyn city directories traced her through the decades—always listed as "wid. Geo." at one address after another: 119 Hamilton Avenue in 1874, 347 Hoyt Avenue by 1880, and finally 194 Nelson Street, where she would die in 1892. Widow of George. Those three words followed her through two decades of American life.

But Margaret was more than a widow. She was the anchor of a family scattered across an ocean—the woman who held the Brooklyn Robertsons together while her children built new lives in this strange American city. Around her, in the dense streets of Brooklyn's working-class neighborhoods, her surviving children married, had children of their own, and established themselves in the trades that would define the next generation.

The Stone Cutter's Family

David Paterson Robertson had been the first to arrive, stepping off the Europa in March 1869 with his wife Elizabeth Gray and their young son William. By 1870, David was working as a stone cutter in Brooklyn's 12th Ward, continuing the masonry tradition his father had practiced in Blairgowrie. His household had already experienced loss—William, the Scottish-born son, was absent from the census, his fate unknown. But two daughters had been born in Brooklyn: Margaret and Elizabeth, markers of a new American generation.

David would continue working stone through the 1870s and beyond. His father George had followed him to America in 1872, hoping perhaps to join his son in the trade—but George had survived only five days before the July heat killed him. Now David carried on alone, the family's stone-cutting tradition transplanted to Brooklyn's building boom.

The Iron Moulder and His Twin

William Fraser Robertson and his twin sister Clementina Stewart Ramsay Robertson had been born on November 17, 1853, in Blairgowrie—the children with the mysterious, distinctive middle names that suggested connections to prominent local families. By the late 1870s, both twins had made their way to Brooklyn, where they would build very different lives.

William had returned to Scotland for his wedding. On December 31, 1878, he married Mary Ann Nisbet at Dollar, in Clackmannanshire—far from Blairgowrie, but still in his native country. The marriage record is rich with family detail: William is listed as a "Sea Moulder, Journeyman," age 24, from Blairgowrie. His parents are named as George Robertson, Mason, and Margaret Paterson. The witnesses include his brothers Alexander Robertson and John Robertson—confirmation that multiple Robertson siblings were still in Scotland at that time.

Mary Ann Nisbet was a domestic servant from Glasgow, age 21, her parents Thomas Nisbet (a labourer, deceased) and Margaret White (also deceased). Both bride and groom had lost parents; both were building something new.

By the 1880 census, William and Mary Ann were established in Brooklyn. William worked as an iron moulder—a skilled trade in the foundries that supplied the rapidly industrializing city. Their son George, age one, had been born in New York. It was the beginning of a very large family: over the next two decades, William and Mary Ann would have at least eleven children, including George (1879), Margaret (1880), William Nisbet (1881), Thomas Nisbet (1885), and Mary Ann (1895), whose birth certificate describes her as the "11th child."

Clementina and the Blacksmith

Clementina, William's twin, had also crossed the Atlantic and settled in Brooklyn. Sometime before 1877, she married Thomas Ferguson, a blacksmith—another skilled tradesman in a city hungry for workers who could shape metal. The 1880 census captured their household: Thomas (age 35), Clementina (25), and two young children, George (3) and Clementina (2), all living in Brooklyn.

Thomas and Clementina would have at least one more child, John B. Ferguson, born around 1881. Their household represented the typical pattern of Scottish immigrant families in Brooklyn—skilled tradesmen, working wives who managed large households, children born in rapid succession, all crammed into the tenements and row houses of the city's working-class neighborhoods.

But Clementina would not live to see her children grow up.

The Youngest Daughter

Isabella Campbell Robertson, the youngest of George and Margaret's children, had been born in 1860—the last child before the great emigration began. Her death certificate would later state she had been in the United States for 39 years, placing her arrival around 1879, when she was about nineteen years old.

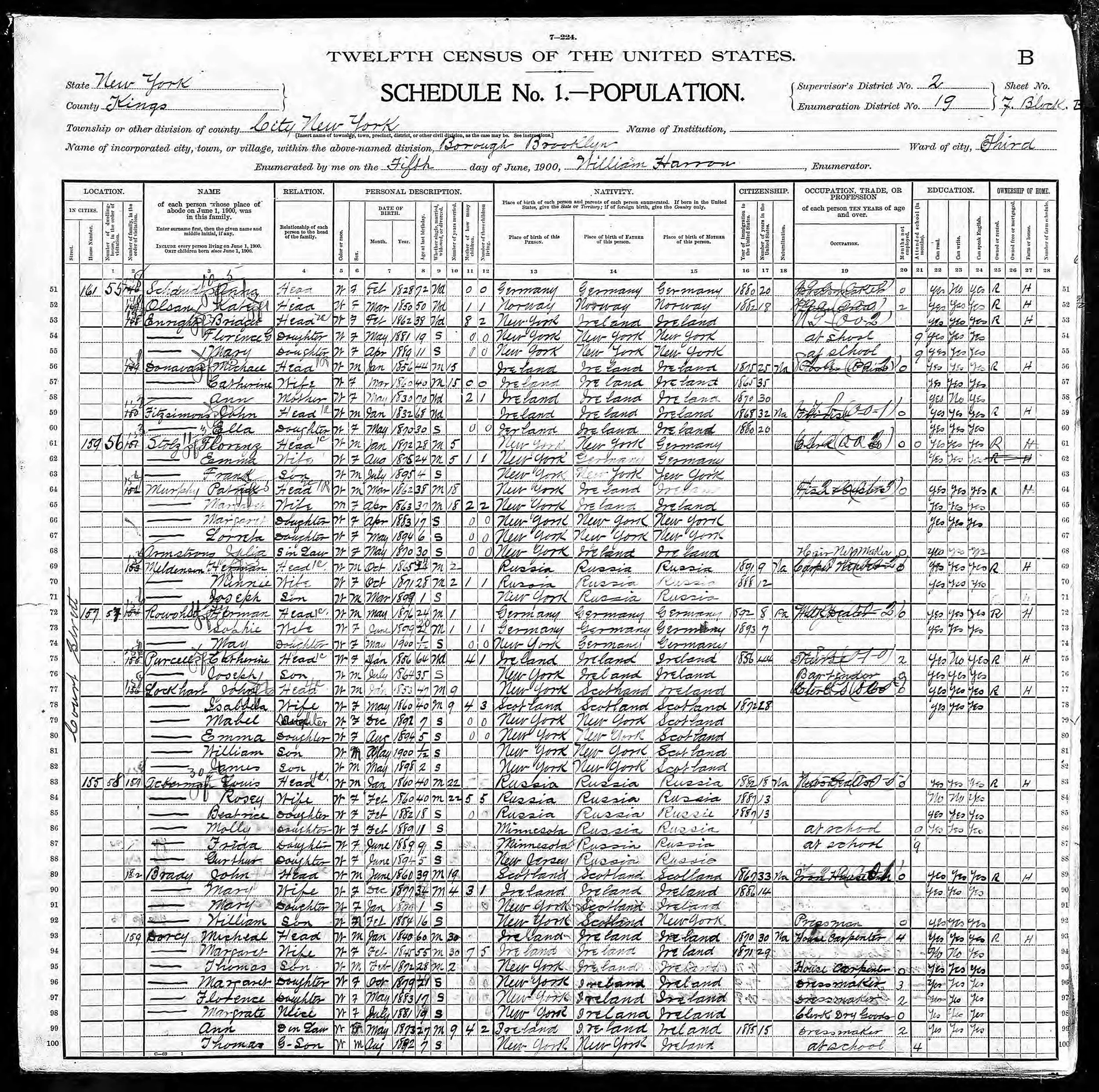

Isabella married John Lockhart sometime around 1891. John was a widower with a young son, James Madden, from his previous marriage. Together, Isabella and John would have four more children: Mable (1893), Amie (1895), Emily (1895), and William Patterson Lockhart (1900). The 1900 census shows Isabella at age 39, keeping house in Brooklyn while John worked as a clerk in a dock office.

Isabella would outlive both her mother and her sister Clementina by more than two decades, dying in 1918. But she too would be buried at Evergreens Cemetery—joining her parents in the same ground where George had been laid to rest forty-six years earlier.

The Devastating Year: 1892

In the summer of 1892, death came twice to the Brooklyn Robertsons.

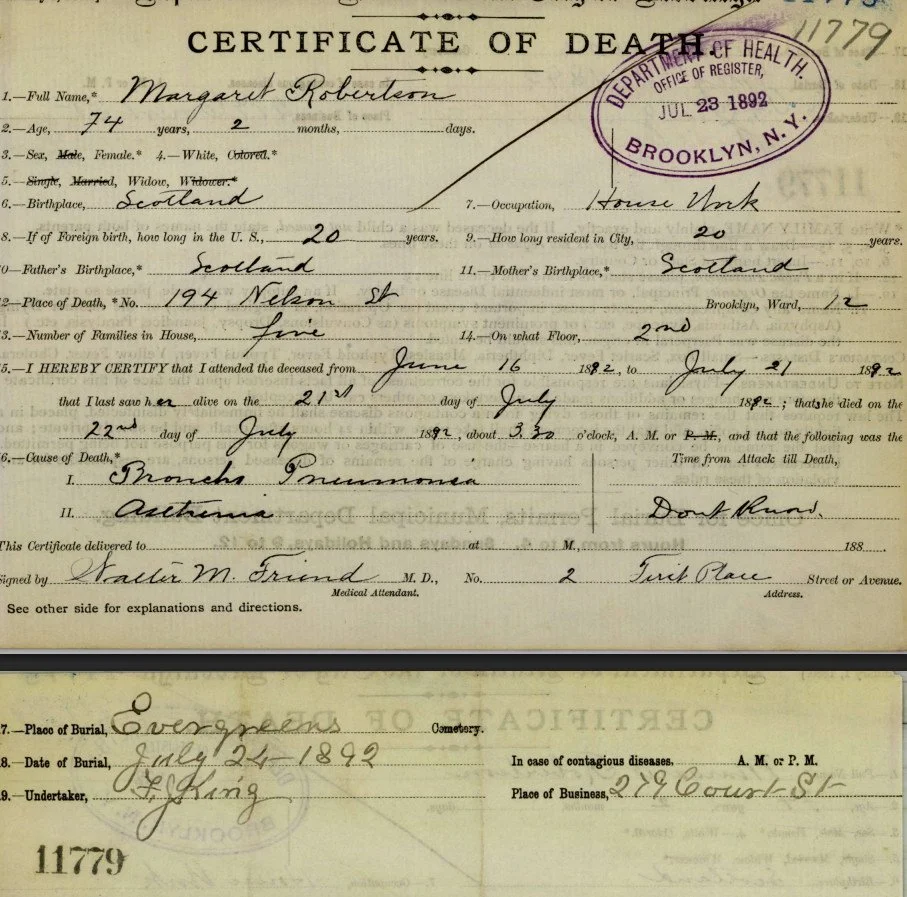

Margaret Paterson Robertson, who had held the family together for twenty years of widowhood, died on July 22, 1892. She was seventy-four years old, living at 194 Nelson Street. The death certificate lists the cause as broncho-pneumonia complicated by asthma. She had been in Brooklyn for twenty years—the same length of time she had been a widow.

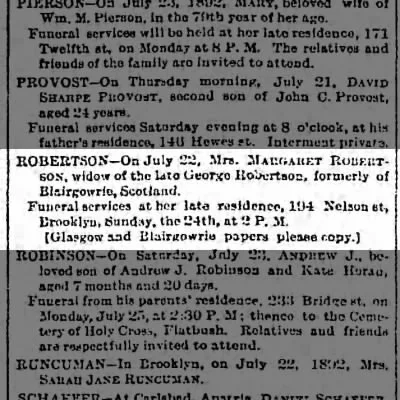

Her obituary, published in the Brooklyn newspapers, spoke of the life she had left behind:

"ROBERTSON — On July 22, Mrs. Margaret Robertson, widow of the late George Robertson, formerly of Blairgowrie, Scotland. Funeral services at her late residence, 194 Nelson st, Brooklyn, Sunday, the 24th, at 2 P.M. (Glasgow and Blairgowrie papers please copy.)"

Even after two decades in America, Margaret wanted people back home to know. She was still, in some essential way, a woman of Blairgowrie.

1892: The Year That Took Everything

Four months apart. Mother and daughter. The matriarch who held the family together and one of the twins born with such distinctive, hopeful names back in Blairgowrie.

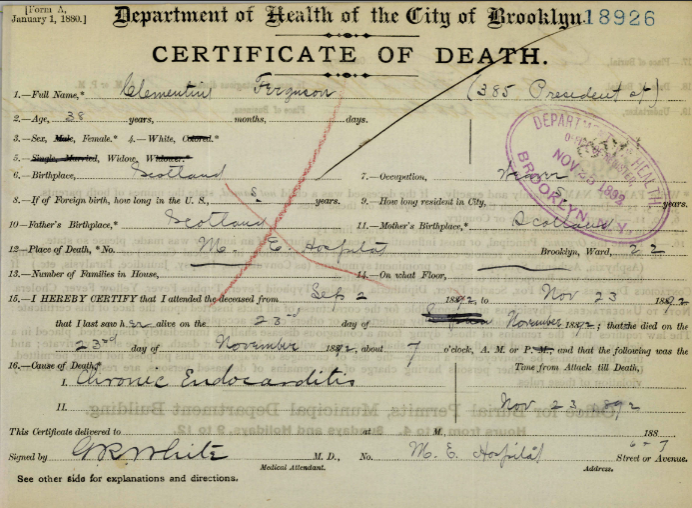

Clementina was thirty-eight years old—the same age her father had been when he married her mother in 1838. She died at 76 East Hopkins Street of chronic endocarditis, a heart condition that had been slowly killing her since at least September. She left behind her husband Thomas and their three children, the youngest only eleven years old.

In a single year, the Brooklyn Robertsons lost both their matriarch and one of the twins who had been born with such distinctive, hopeful names back in Blairgowrie. Margaret had lived long enough to see grandchildren born in America; Clementina had not.

After 1892

The surviving siblings continued their lives in Brooklyn. William Fraser Robertson and his wife Mary Ann raised their enormous family through the turn of the century. The 1900 census found them still in Brooklyn, William still working as an iron moulder at age 46, surrounded by children. What became of them after 1900 remains unclear—no definitive death record has been found for William or Mary Ann.

Isabella Lockhart raised her children through the 1900s and 1910s. The census records trace her household: John working as a clerk, the children growing up, the family moving through Brooklyn's neighborhoods. Emily, one of the daughters, died young in 1910, just fifteen years old.

Isabella herself died on February 15, 1918, at Long Island College Hospital. She was fifty-seven years old, widowed. The cause of death was lobar pneumonia—the same disease that had killed her mother twenty-six years earlier, now spreading through the population in the early waves of what would become the devastating 1918 influenza pandemic.

Her death certificate contains a small error that speaks to the confusion of immigrant families trying to preserve their histories: it lists her father as "James Robertson" rather than George. But it correctly names her mother as Margaret Patterson, and correctly identifies both parents' birthplace as Scotland.

Isabella was buried at Evergreens Cemetery on February 17, 1918—the third generation of Robertsons to be laid to rest in that ground. George had been first, in 1872. Margaret had followed in 1892. Now Isabella joined them, the youngest daughter coming home to her parents at last.

Evergreens

Evergreens Cemetery, established in 1849, became the final gathering place for the Brooklyn Robertsons. George Robertson was buried there on July 3, 1872, just one day after his death from sunstroke. Margaret Paterson Robertson joined him on July 24, 1892. Emily Lockhart, Isabella's daughter, was buried there in 1910. And Isabella herself was laid to rest there on February 17, 1918.

All were buried in the Pathside section—an unmarked area with no headstones, no monuments, no way for future generations to find the exact spots where they lie. It was a common choice for working-class immigrants: economical burial in consecrated ground, dignity without display.

Today, a visitor to Evergreens can walk the paths near where the Robertsons are buried, but cannot find their graves. They are there, somewhere in the green expanse—George and Margaret, Emily and Isabella, together in death as they had been scattered in life.

But not all of George's children came to Brooklyn. Not all were buried at Evergreens. The stones were scattered farther than that—across Canada, across the Atlantic to Liverpool, and one who never left Scotland at all.

Their stories belong to the final chapter.

The Story Continues: Mary Ann wandered through Canada for decades. James became a gamekeeper in Liverpool. Alexander never left Scotland. And some of the children simply disappeared from the records entirely. Episode 5: Scattered Fates.

Evidence Analysis

Reconstructing the Brooklyn Robertsons requires correlating city directories, census records, vital records, and cemetery documentation across four decades. Several patterns emerge from this analysis.

Margaret's Two Decades

The Brooklyn directories provide consistent documentation of Margaret's presence from 1874 to her death in 1892. Her address changes—119 Hamilton Avenue, 347 Hoyt Avenue, 194 Nelson Street—but her status remains constant: "wid. Geo." or "wid. George." She was the fixed point around which her children orbited.

The 1878 Marriage Record

William Fraser Robertson's marriage to Mary Ann Nisbet provides crucial family information. It confirms George Robertson's occupation as Mason and Margaret's maiden name as Paterson. The witnesses—Alexander and John Robertson—prove that multiple siblings were still in Scotland in late 1878, and that Alexander (the one who would never emigrate permanently) maintained contact with his Brooklyn-bound brother.

The Devastating Year

Margaret and Clementina died within four months of each other in 1892. Margaret's death on July 22 preceded Clementina's on November 23. The timing suggests coincidence rather than contagion—Margaret died of broncho-pneumonia with asthma, Clementina of chronic endocarditis. But the effect on the family must have been devastating.

Evergreens Cemetery

Cemetery records confirm George (July 3, 1872), Margaret (July 24, 1892), Emily Lockhart (1910), and Isabella (February 17, 1918) were all buried in the Pathside section. This unmarked area means no headstones survive, but the family connection to this specific cemetery is clear across three generations.

Document Errors

Isabella's 1918 death certificate lists her father as "James Robertson" rather than George—a common type of error in immigrant death records, often caused by informant confusion. The correct identification of her mother as Margaret Patterson helps validate the record despite this error.

Primary Source Documents

The following documents trace the Brooklyn Robertsons through two generations—from Margaret's decades of widowhood to the marriages, births, and deaths that shaped this immigrant family.

Sources

Brooklyn City Directories, 1874, 1880 (Margaret Robertson, widow George).

Statutory Registers, Dollar 465/ Marriages (1878 marriage of William Fraser Robertson and Mary Ann Nisbet). National Records of Scotland.

1880 U.S. Census, Brooklyn, Kings County, New York (William Robertson household; Thomas Ferguson household).

1900 U.S. Census, Brooklyn, Kings County, New York (John Lockhart household).

Certificate of Death, Margaret Robertson, July 22, 1892, Kings County, New York. NYC Municipal Archives.

Certificate of Death, Clementina Ferguson, November 23, 1892, Kings County, New York. NYC Municipal Archives.

Certificate of Death, Isabella Lockhart, February 15, 1918, Kings County, New York. NYC Municipal Archives.

Birth Certificate, Mary Robertson (daughter of William Fraser Robertson), March 24, 1895, Brooklyn. NYC Municipal Archives.

"Mrs. Margaret Robertson" [obituary], Brooklyn newspaper, July 1892.

Evergreens Cemetery Records, Brooklyn, New York (George Robertson burial July 3, 1872; Margaret Robertson burial July 24, 1892; Isabella Lockhart burial February 17, 1918).

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY