Irish Genealogy Challenges

IRISH GENEALOGY

Irish Genealogy Challenges

What Every Researcher Faces

And How Professionals Work Around Them

"When a professional genealogist at the county library tells you 'we are at a standstill,' you know you've hit a genuine dead end—not a failure of research skills, but an absence of surviving evidence."

If you've ever tried to trace your Irish ancestors back beyond the mid-1800s, you've probably hit what genealogists call "the brick wall." You're not alone. Irish genealogy is widely considered among the most challenging in the world—and for good reason.

After seven years researching my own Hamall family from County Monaghan, I've encountered every obstacle the records can throw at a researcher. Some I've overcome through creative methodology. Others remain unsolved. Here's what you're up against—and what you can do about it.

WHAT YOU'LL LEARN

- Why records are missing: Census destroyed, parish registers that start too late

- The name problem: How to find YOUR John Hamill among dozens

- DNA limitations: When genetics can't solve what documents can't

- Methods that work: Occupational tracking, sponsorship analysis, and creative breakthroughs

1. The Great Record Gap

The single biggest challenge in Irish genealogy is the absence of records for the period when most of our ancestors lived. To find parents for someone born in the 1820s or 1830s, you need records from the late 1700s or early 1800s. Those records largely don't exist.

What Records Exist—and Don't Exist

1864 Civil registration of births, marriages, deaths begins

1847-64 Griffith's Valuation (land records—no relationships shown)

1830s Most Catholic parish registers begin (some later, some earlier)

1823-37 Tithe Applotment Books (names heads of household—no relationships)

For my Hamall family, I needed to find records from around 1810-1820—the likely marriage date of Owen Hamall's grandparents. The parish registers for Donaghmoyne don't begin until 1835. The census records that might have helped were destroyed. I was looking for people who lived and died in a documentary void.

When Registers Do Exist, They May Not Help

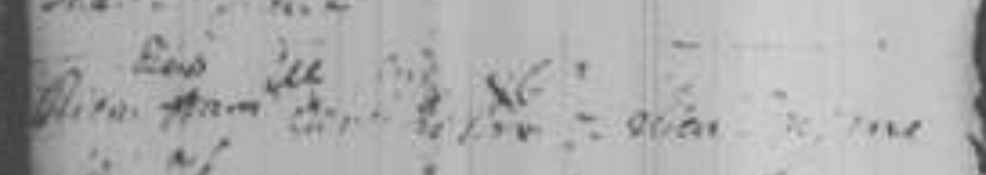

Even when parish registers survive, the physical condition can make them nearly impossible to read. Here's an actual page from the Donaghmoyne registers, showing baptisms from the 1840s:

A baptism register page from 1846. Water damage, fading ink, and difficult handwriting

make many entries impossible to decipher. Is one of these entries my ancestor? I can't tell.

I spent hours examining this page. Somewhere on it might be a baptism for an Owen Hamill. Or it might not. The damage is too severe to know.

A cropped section that might read "Owen Ham..." but the damage makes certainty impossible.

This is the reality of Irish parish register research.

The Registers You Need May Not Exist at All

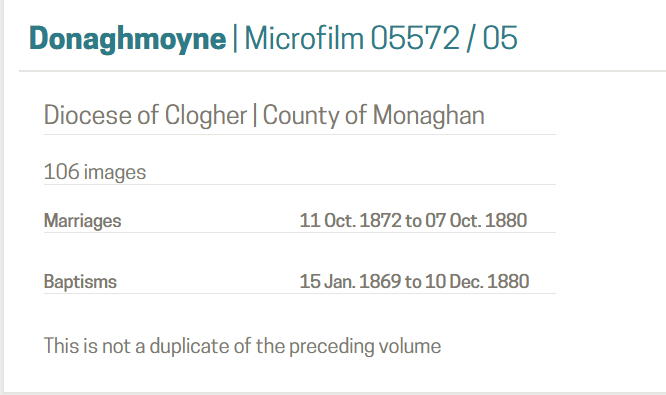

For Donaghmoyne parish, the earliest surviving registers begin in 1869—far too late to capture anyone born before 1850. The microfilm availability tells the story:

The National Library of Ireland's listing for Donaghmoyne parish: baptisms begin January 1869,

marriages October 1872. If your ancestor was baptized or married before those dates, no record survives.

2. When Even the Experts Can't Help

Early in my research, I contacted the Monaghan County Library, hoping their local history staff might know of records I hadn't found. The response was honest—and sobering:

"Unfortunately I am unable to add any further information to your ancestor's search and this is due to the lack of records for the time you need. I could not find any more birth records relating to siblings of Mary. So Mary without the records, we are at a standstill!"

— Catríona Lennon, Staff Officer/Local History & Genealogy, Monaghan County Library

When a professional genealogist at the county library tells you "we are at a standstill," you know you've hit a genuine dead end—not a failure of research skills, but an absence of surviving evidence.

3. The Name Problem

Even when records do exist, finding your specific ancestor among dozens of people with the same name presents another challenge. Irish naming patterns concentrated the population into a small pool of surnames and given names.

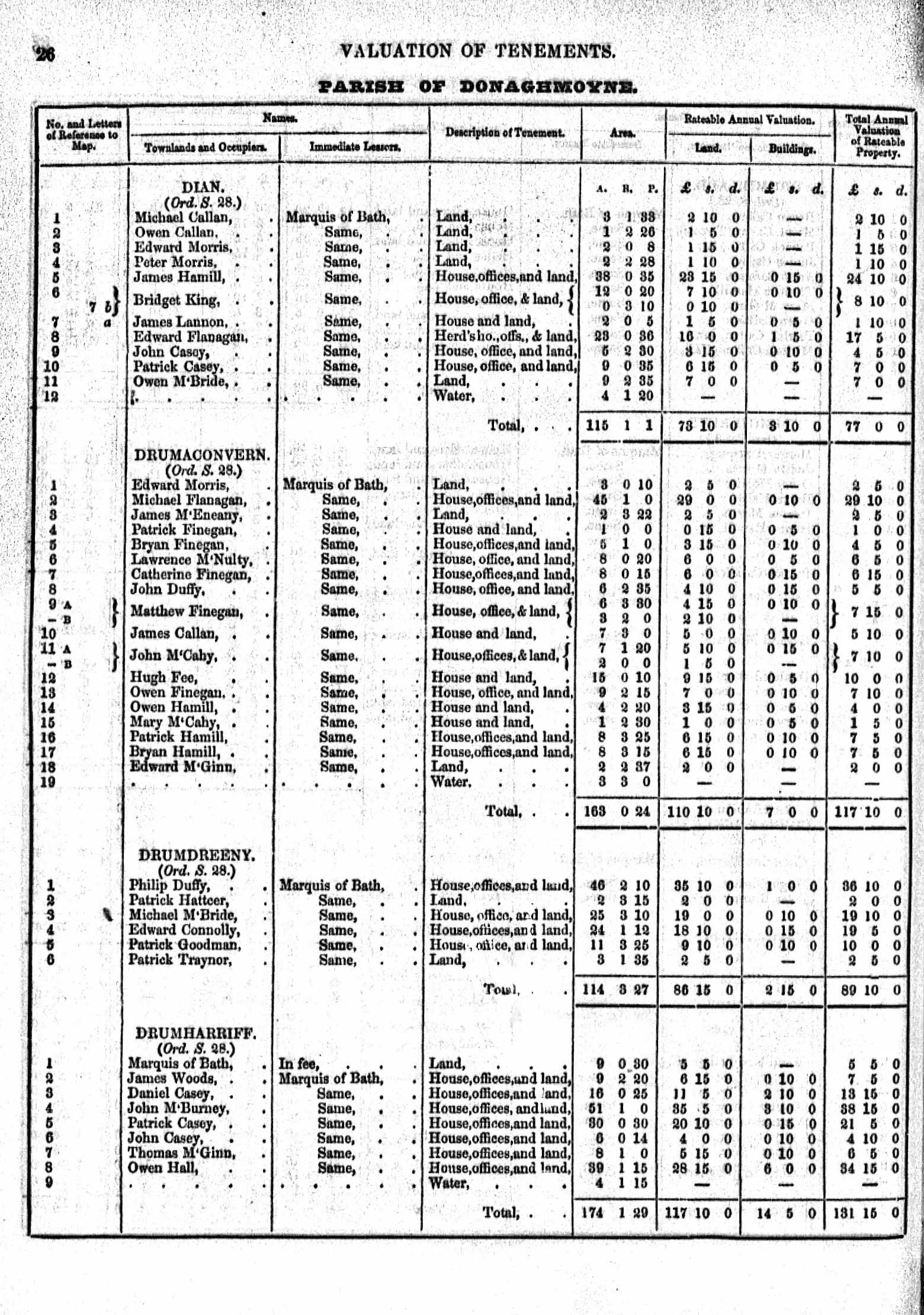

Look at this page from Griffith's Valuation (1861) for Donaghmoyne parish. Count the Hamills:

Griffith's Valuation for Donaghmoyne parish, 1861. In just two townlands—Dian and Drumaconvern—

I count James Hamill, Owen Hamill, Patrick Hamill, and Bryan Hamill.

Which Owen is mine? Which James? The records don't say.

And it gets worse. The same surname appears with multiple spellings—sometimes on the same document:

- Hamall — how my Chicago ancestor spelled it

- Hamill — the most common modern spelling

- Hammel — used by the Wisconsin branch

- Hammil — appears on some church records

- Hamil — occasional variant

These weren't different families—they were the same families, with clerks spelling the name however it sounded to them. Search for one spelling, and you'll miss records filed under another.

4. The Great Famine Factor

The Irish Famine (1845-1852) didn't just kill a million people and force another million to emigrate. It scattered families across the globe, often with no forwarding address. It emptied townlands that had been continuously occupied for centuries. And it happened just before systematic record-keeping began.

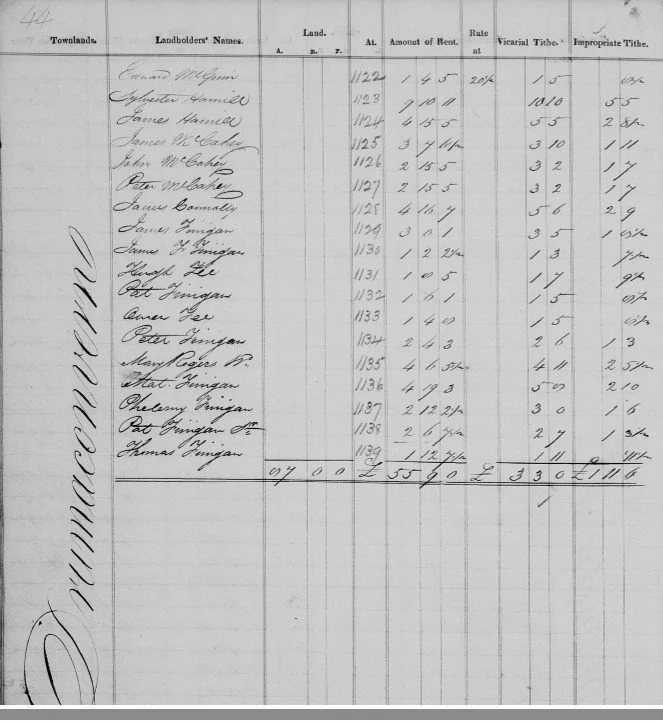

The Tithe Applotment Books from the 1820s and 1830s show who was in a townland before the Famine. Griffith's Valuation shows who was there after. But connecting the two—proving that a Hamill in 1847 was the son of a Hamill in 1827—often proves impossible.

Tithe Applotment records from the 1820s show Sylvester Hamill and James Hamill in the parish.

But what happened to them? Did they die in the Famine? Emigrate? Move to another townland?

The records don't tell us.

5. When DNA Can't Save You

Many researchers turn to DNA testing hoping genetics will solve what documents cannot. And DNA can be powerful—but it has its own limitations, especially for Irish families.

The Endogamy Problem

In rural Irish parishes, everyone was related to everyone else. Families intermarried for generations within the same small area. This "endogamy" means DNA matches may appear stronger than they actually are—or you may match someone through multiple pathways, making it impossible to identify the specific connection.

The Genealogical Bottleneck

For my own research, the biggest DNA obstacle is what geneticists call a "bottleneck." My great-great-grandfather Owen Hamall had only two children who survived to adulthood. His son Thomas Henry had only one child. That child, Thomas Eugene, had only one child—my father, Thomas Kenny Hamall.

My father had six children, five of whom have tested. But we have no first cousins. No second cousins. No third cousins. The family came within one generation of extinction, and while it survived, the lack of cousin matches makes DNA triangulation nearly impossible within our line.

We can prove who we are. We can't use DNA to prove where we came from.

The Lesson: DNA testing works best when you have multiple descendants from multiple children to compare. If your family tree narrows to a single line for several generations, DNA may confirm your documented relationships but fail to extend them further back.

6. Breaking Through: When Creative Methods Work

Despite these challenges, breakthroughs are possible. They just require creative thinking, patience, and sometimes luck. Here are two methods that worked for me:

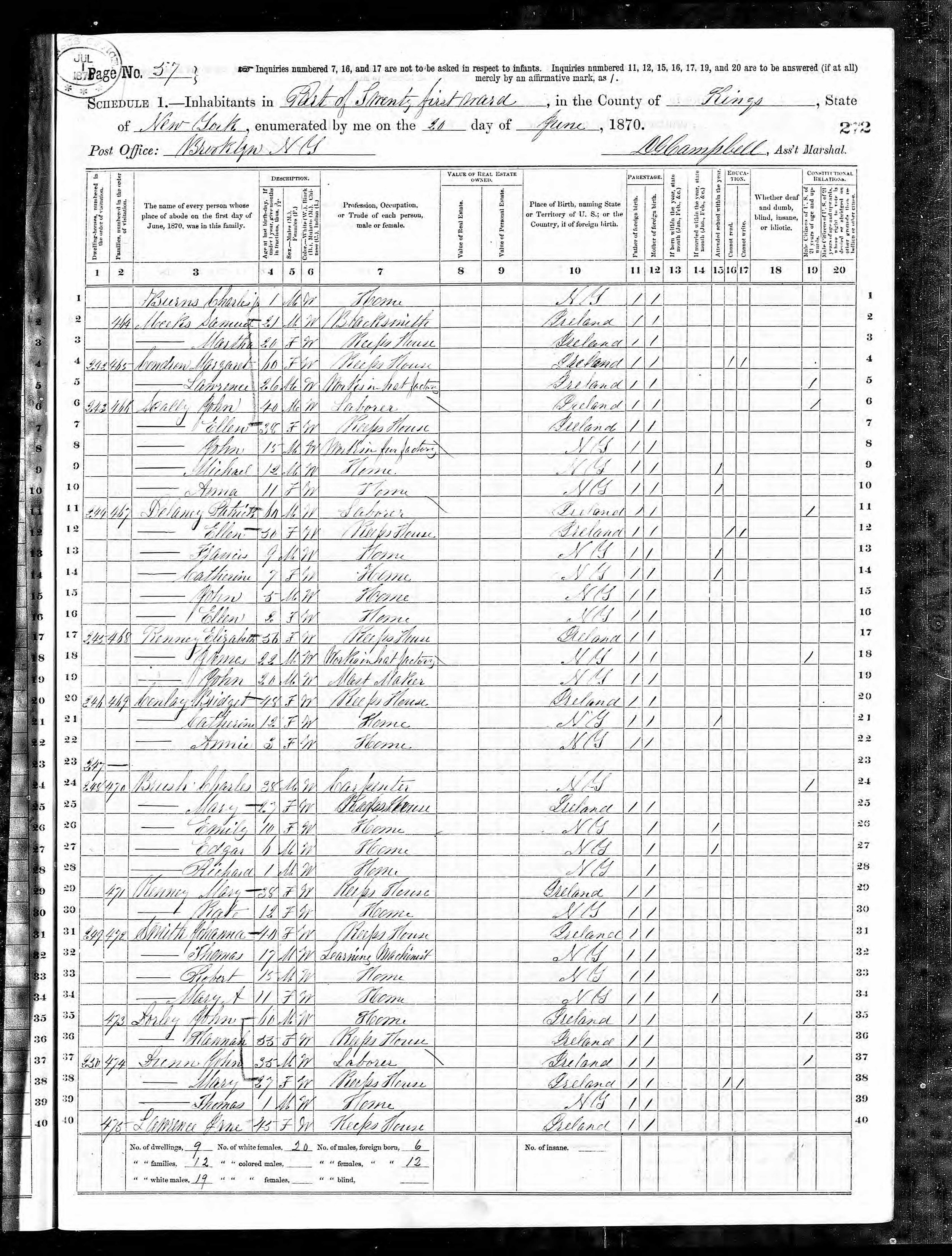

Occupational Tracking: The Brooklyn Mat Maker

When I researched my Kenny ancestors in Brooklyn, I faced the ultimate common-name problem: John Kenny. Brooklyn directories and census records contained hundreds of John Kennys.

What saved the case was an unusual occupation. In the 1870 census, my John Kenny was listed as a "Mat Maker"—a straightforward manufacturing role in the textile trades. The occupation was part of the broader light manufacturing industries present in 19th-century New York. This was distinctive enough to track him through decades of records.

Why Occupational Tracking Works

The logic behind the method

In 19th-century urban communities, skilled trades provided more stable identity markers than names, ages, or even addresses. The career progression from "Mat Weaver" to "Matmaker" to "Hatter" represents logical skill development within related textile trades—a sequence that would be extremely unlikely to appear randomly.

Consistency Across Sources

- Names could be misspelled

- Addresses could change

- Occupational designations remained stable

- Appeared in multiple record types

Skill Development Patterns

- Entry-level to advanced progression

- Logical within textile trades

- Extremely unlikely to be random

- Tracks life stages naturally

Community Context

- Matches Irish immigrant patterns

- Textile trades = economic mobility

- Family business connections

- Brother James was also a hatter

The Career Path That Solved the Mystery

13+ Years of Documented Occupational Progression

Mat Weaver (1870s) → Matmaker (1879-1888) → Hatter (1888)

No other John Kenny in Brooklyn records could match this progression.

The 1870 census breakthrough: John Kenny, age 29, "Mat Maker," living with his widowed mother Elizabeth.

This distinctive occupation became the key to tracking him through dozens of records

where the common name alone would have failed.

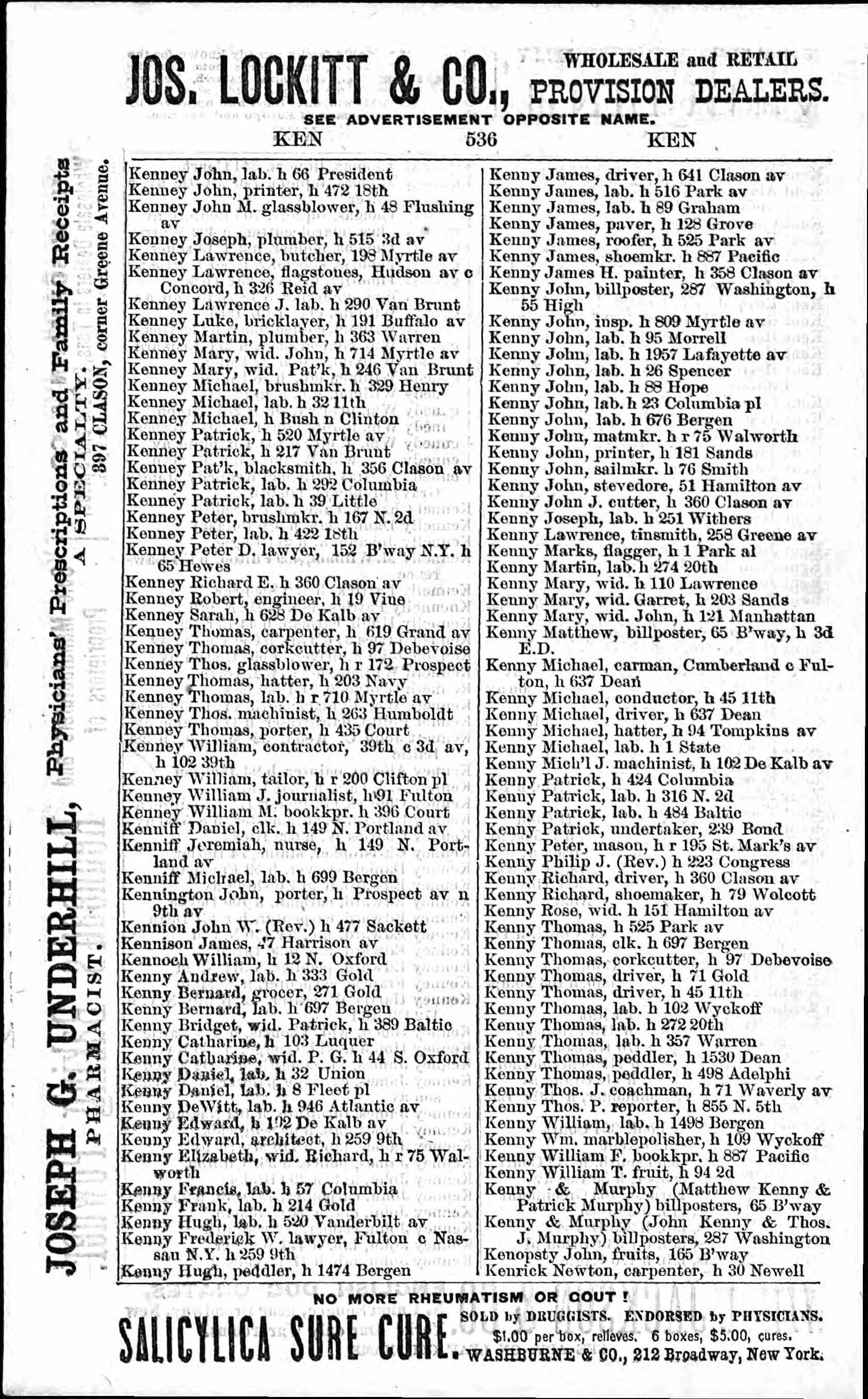

The city directories confirmed and extended this identification:

Brooklyn City Directory, 1879: "Kenny John, matmkr, h r 75 Walworth" —

living at the same address as "Kenny Elizabeth, wid. Richard."

Mother and son confirmed at the same location, occupation matching the census.

CASE STUDY

The Brooklyn Mat Maker

How occupational tracking solved an "impossible" common-name case where DNA analysis failed.

Read the Full Case StudyReciprocal Sponsorship: The Half-Brother Discovery

For my Hamall research, the breakthrough came from an unexpected source: Catholic baptism records in Chicago. Not the baptisms themselves, but the sponsors (godparents) named on those records.

In March 1883, my great-great-grandfather Owen Hamall baptized a son named William. The sponsor was recorded as "William Thornton." Three months later, William Thornton baptized a daughter named Mary Margaret—and Owen Hamall served as her sponsor.

The breakthrough document: William Hammil's baptism, March 1883, with "William Thornton" recorded as sponsor.

This reciprocal sponsorship pattern (Owen sponsored William's child; William sponsored Owen's child)

proved a close family relationship.

The "Thornton Hammil" Mystery

The Challenge

The 1880 Census showed the "Hammil" household with "Thornton Hammil" listed as Owen's brother—a mysterious entry that launched six years of investigation. Who was this person with a surname for a first name?

William Hamall's baptism gave us the name "William Thornton" as sponsor—and then we found the baptism for William Thornton's daughter Mary Margaret, with Owen Hamall serving as her sponsor. The reciprocal pattern proved the relationship.

This reciprocal sponsorship—each man standing as godfather to the other's child—was a pattern typically seen between brothers. Further research confirmed that William Thornton was Owen's half-brother through their mother Mary McMahon's remarriage after their father Henry died.

A document from Chicago solved a mystery about a family that left Ireland in 1850. That's the nature of Irish genealogy: sometimes the answers are found thousands of miles from where the questions began.

CASE STUDY

The Owen Hamall Mystery

Seven years of research, a half-brother discovery, and the limits of what DNA can prove about Irish origins.

Read the Full Case StudyThe Path Forward

Irish genealogy is hard. The records are incomplete, the names are duplicated, and DNA often raises more questions than it answers. But "hard" doesn't mean "impossible."

Success in Irish research requires:

- Patience — Some of my breakthroughs came after years of searching

- Creativity — When direct evidence doesn't exist, indirect evidence may

- Collaboration — Other researchers may have pieces you're missing

- Honesty — Knowing when evidence is suggestive versus conclusive

- Persistence — New records are digitized every year; today's dead end may open tomorrow

If you're stuck on your Irish ancestors, you're in good company. The best genealogists in the world hit walls in Irish research. The difference is knowing which walls might eventually fall—and which require learning to work around them.

Stuck on Your Irish Ancestors?

Professional genealogy research can help you navigate the gaps, identify creative approaches, and make progress where you've hit walls.

Let's Talk About Your Research

Mary Hamall Morales

Founder, Storyline Genealogy

Professional genealogist specializing in Irish, Scottish, French-Canadian, and Philippine heritage research. After a 45-year career in healthcare, Mary now focuses full-time on complex cases involving DNA analysis, occupational tracking, and international archival research. Currently documenting the Donaghmoyne Network—four interconnected families from County Monaghan, Ireland.

I specialize in transforming traditional genealogy research into compelling family narratives. Through comprehensive historical research and strategic DNA analysis, I uncover not just who your ancestors were, but how they lived, survived, and shaped your legacy.

What Sets Me Apart: I solve genealogy mysteries that have stumped families for generations, integrate DNA evidence to enhance family stories, and create professional narratives that connect generations.

Continue Reading

The Owen Hamall Mystery →

Seven years of research, a half-brother discovery, and the limits of what DNA can prove.

The Brooklyn Mat Maker →

When occupational tracking solves impossible common-name cases.

The Donaghmoyne Network →

Four families, one parish, DNA connections across generations.