Marie Lorgueil: Fighting a Baron

Fighting a Baron

On September 13, 1690, a French nobleman ran Marie Lorgueil's husband through with a sword and fled into the wilderness. Toussaint Hunault died that day on the streets of Montreal—killed not by Indigenous warriors in some frontier battle, but by one of his own: Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac, Lieutenant of a Company of Marines. Marie was fifty-six years old. She had eight living children. Her husband of thirty-six years was dead. And she had a choice to make.

This episode examines how Marie Lorgueil navigated the colonial legal system after her husband's murder—and why she ultimately sold her legal rights for 520 livres and debt forgiveness. Through primary sources from the Archives Nationales du Québec and genealogical research by Peter Gagne, we reconstruct not just what happened, but what it reveals about justice, power, and survival in seventeenth-century New France.

PART I: THE NARRATIVE

Before the Sword

To understand Marie's choice, you need to understand what she had already survived.

She came to New France in 1654 as a Fille à Marier—one of the marriageable women who arrived before the Crown-sponsored Filles du Roi program began in 1663. She was actually twenty years old when she arrived, though she told colonial officials she was sixteen. In the colonial marriage market, those four years mattered. Four years could mean the difference between finding a husband or being passed over. So Marie lied, married Toussaint Hunault three months after arriving, and began building a life in the wilderness.

Over the next twenty-one years, she bore ten children. Two died young—little Mathurin at age six in 1671, the first Toussaint just after his second birthday in 1673. But eight survived, which was actually remarkable for the seventeenth century. Marie had done everything right. She had built a family. She had created stability in an unstable world.

And then 1689 arrived.

On August 17 of that year, Iroquois warriors raided the settlement of Lachenaie. Among the dead was Marie-Thérèse, Marie's twenty-six-year-old daughter, married thirteen years to Guillaume Leclerc. The kind of death that was supposed to be a risk when you lived on the frontier. The kind of death Marie might have steeled herself for, even if you are never really prepared to bury your child.

But thirteen months later, when the sword found Toussaint, that was different.

This was not warfare. This was not the wilderness. This was murder in the streets of Montreal by a French military officer. This was supposed to be the safe part of the colony.

The Sword

September 13, 1690. Toussaint Mathurin Hunault dit Deschamps, habitant farmer, approximately sixty-two years old. Killed by Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac, Lieutenant of a Company of Marines. Method: run through with a sword.

The Baron fled after the attack. Whereabouts unknown.

We do not know why. The historical record does not preserve the motive—only the fact. A nobleman used his sword on a commoner and disappeared into the vast colony. Perhaps it was a dispute. Perhaps it was something else entirely. What we know is the outcome: Toussaint dead, the Baron gone, and Marie suddenly a widow at fifty-six.

The Impossible Position

Let us be clear about Marie's situation in September 1690.

She was a widow with no income and eight children to support, ranging from adults to fourteen-year-old Charles. Her husband had been murdered by a nobleman—not just any nobleman, but an active military officer with connections, resources, and the kind of social standing that could make problems disappear.

And there was debt. Toussaint owed money to Charles de Couagne, one of Montreal's wealthy merchants. We know from a 1683 notarial obligation that the family had financial struggles—seven years before the murder, Toussaint and Marie owed their own son André 307 livres. The debt to Couagne added another layer of pressure to an already impossible situation.

Marie could have done what plenty of widows did: accepted her fate, tried to scrape by, hoped her adult children could support her. But Marie was not that kind of woman. She had lied about her age to improve her chances in 1654. She had survived thirty-six years in New France. She had buried two children and kept going. She was not about to let her husband's murderer walk away without consequence.

So in 1691, Marie and her children filed suit against Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac.

The Math of Justice

Here is where the story gets complicated, because justice in 1691 New France was neither simple nor quick nor cheap.

To pursue a case against a nobleman meant hiring legal representation (expensive), waiting months or years for trial (no income during wait), facing a defendant with connections to colonial power structure, hoping the court would side with a habitant widow over a Baron, hoping the Baron could even be found and compelled to appear, hoping for a verdict in your favor, hoping for damages to be awarded, and hoping those damages could actually be collected.

That is a lot of hoping, with very little guarantee and mounting costs.

And while Marie was hoping, she still had to eat. Her children still had to eat. The debt to Couagne still existed.

Then Charles de Couagne made her an offer.

The Deal

Here is what Couagne proposed: He would pay Marie and her children 520 livres immediately. He would also forgive all of Toussaint's outstanding debt. In exchange, Marie and her children would cede to Couagne all rights to their inheritance from Toussaint and any possible damages that might be won in the trial against Baron de Blaignac.

In other words: Give me your legal case, and I will give you cash now.

Let us put 520 livres in perspective. For a habitant family in the 1690s, this was substantial—roughly equivalent to one to two years of income for an agricultural worker. It could purchase a cow (20-30 livres) or two oxen (100-150 livres each). Combined with the debt forgiveness, this deal represented immediate financial stability for a desperate widow.

But here is what Marie was giving up: If Couagne successfully sued the Baron and won, say, 2,000 livres in damages, Couagne would keep it all. If Toussaint had property or inheritance rights worth more than 520 livres, Couagne got that too. Marie was selling the possibility of future justice for the certainty of present survival.

The question is: Was she making a rational choice or a desperate one?

The answer is: both.

The Widow's Calculus

Put yourself in Marie's position for a moment.

You are fifty-six years old in 1690. Your daughter was murdered by Iroquois raiders thirteen months ago. Your husband was just murdered by a French baron with a sword. You have eight children, including teenagers still at home. You have no income. You have debt. And you are supposed to take on the colonial legal system against a nobleman?

Even if you won—and that is a big if—it could take years. Years during which you are spending money you do not have on lawyers. Years during which you are waiting for a verdict that might never come. Years during which the Baron might simply disappear into the wilderness or use his connections to avoid consequences. Years during which your family is sinking deeper into poverty.

Or: You could take 520 livres today. You could have the debt wiped clean. You could feed your family. You could survive.

Marie chose survival.

Couagne was not offering charity. He was making an investment. He was betting that as a wealthy merchant with resources and time, he could pursue the case against Baron de Blaignac and potentially win more than 520 livres. But he was also taking on all the risk. If the case went nowhere, he was out 520 livres plus the debt forgiveness.

Marie was trading potential future justice for guaranteed present survival. And when you look at it that way, it is not really a choice at all.

What Happened to the Baron?

Here is where the story frustrates, because we do not know.

Did Couagne pursue the case? Did he ever find Baron de Blaignac? Did the Baron face any consequences for running a habitant through with a sword in broad daylight and fleeing?

The historical record is silent.

It is possible the Baron was never caught. It is possible he used his rank and connections to avoid prosecution. It is possible he was quietly transferred to another post. It is possible Couagne decided pursuing a noble was not worth the trouble, even with the case in hand.

What we know for certain is this: Marie never saw justice done with her own eyes. She never got to stand in court and watch her husband's murderer be held accountable. She got 520 livres and the ability to keep her family fed.

That is not nothing. But it is also not justice.

The Last Decade

Marie lived another ten years after Toussaint's murder, mostly in Varennes with her son André. She watched her children marry and have children of their own. She became a grandmother. She witnessed one more family crisis—her son Toussaint arrested for illegal trading in June 1699—but she did not have to face it alone.

She died on November 29, 1700, at age sixty-six, surrounded by the family she had fought so hard to protect.

In her lifetime, Marie had lied about her age to improve her chances in a new world, survived the death of two young children, endured the murder of her adult daughter, endured the murder of her husband by a nobleman, made the hardest choice a widow could make, and kept her family together through it all.

That is not resignation. That is strategy. That is survival.

PART II: EVIDENCE ANALYSIS

The Research Question

How does a 56-year-old widow with no income, eight children, and existing debt pursue justice against a nobleman who murdered her husband with a sword and fled—in colonial New France, 1690?

This evidence analysis examines the primary sources that document Marie Lorgueil's legal response to her husband's murder and evaluates what they reveal about colonial justice, women's legal agency, and economic survival strategies.

Evidence Item 1: The Murder

Source Information

- Event: Death of Toussaint Mathurin Hunault dit Deschamps

- Date: September 13, 1690

- Location: Montreal area, New France

- Cause: Murdered by Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac

- Method: Run through with sword

- Murderer's rank: Lieutenant of a Company of Marines (French military officer)

- After murder: Dumont fled

Analysis

The murder record establishes several critical facts for understanding Marie's subsequent legal response. First, the victim was clearly identified as Toussaint Hunault, connecting this event to the family documented in the 1666 census and the 1683 debt obligation. Second, the perpetrator was identified by name, title, and military rank—establishing not just who committed the murder but the significant power differential between victim and perpetrator.

The method (sword) and the perpetrator's flight after the attack indicate this was not self-defense but a deliberate act followed by evasion of consequences. The timing—13 months after Marie-Thérèse's murder by Iroquois raiders—places Marie's situation in context: she experienced two violent deaths in her immediate family within just over a year.

Evidence Item 2: Pre-Existing Debt (1683)

Source Information

- Document Type: Notarial obligation

- Date: November 15, 1683

- Debtors: Toussaint Hunault and Marie Lorgueil

- Creditor: André Hunault (their son)

- Amount: 307 livres

- Repository: Notarial records, French Regime

Analysis

This document proves the Hunault family was already experiencing financial difficulties seven years before Toussaint's murder. The amount—307 livres—was substantial, roughly equivalent to one to two years of wages for a habitant. The fact that the creditor was their own son André suggests either a business arrangement, early inheritance advance, or family assistance during a difficult period.

This pre-existing financial stress is crucial context for understanding why Marie accepted the 1691 settlement. She did not enter widowhood from a position of financial stability—she entered it already burdened by debt.

Evidence Item 3: The Widow's Settlement (1691)

Source Information

- Document Type: Cession de droits (transfer of rights)

- Date: 1691

- Sellers: Marie Lorgueil and her eight children

- Buyer: Charles de Couagne (Montreal merchant)

- Payment: 520 livres

- Additional benefit: Complete dissolution of Toussaint's debt to Couagne

- Rights transferred: All inheritance rights AND all rights to damages from lawsuit against Baron de Blaignac

- Source: Referenced in Peter Gagne research

Analysis

This is the central document of the case. It proves several important facts:

- Marie and her children filed suit against Baron de Blaignac. This establishes that despite the power differential, Marie took legal action. She did not passively accept her husband's murder.

- The family acted collectively. All eight surviving children joined with Marie in the settlement, suggesting either legal necessity under the Custom of Paris or family solidarity.

- Charles de Couagne saw value in acquiring the case. A savvy merchant would not pay 520 livres plus forgive an existing debt unless he believed the potential return exceeded his investment.

- Marie had legal standing under colonial law. As a widow, she could enter into binding legal contracts and transfer property rights—evidence of women's legal agency in New France.

Economic Context: What 520 Livres Actually Meant

To evaluate whether Marie made a reasonable decision, we must understand the economic context of 1690s New France:

| Item | Approximate Value |

|---|---|

| Annual wages (agricultural worker) | 250-400 livres |

| One cow | 20-30 livres |

| One ox | 100-150 livres |

| Pierre Hunault's two oxen (1694 lawsuit) | 200-300 livres |

| Marie's settlement | 520 livres + debt forgiveness |

The settlement represented approximately 1-2 years of income, plus the elimination of the debt to Couagne. This was not a trivial sum—it provided genuine financial stability for a widow with eight children.

Gaps in the Evidence

Despite extensive archival research, several key questions remain unanswered:

- Motive: No record explains why Baron de Blaignac killed Toussaint Hunault.

- Baron's fate: No trial record, punishment, or transfer order has been located for Gabriel Dumont.

- Couagne's pursuit: No evidence confirms whether Couagne pursued the case after acquiring Marie's rights.

- Amount of Couagne debt: The settlement references debt forgiveness, but the specific amount owed to Couagne is not preserved.

These gaps are significant but do not undermine the core findings. The silence in the record—particularly regarding the Baron's fate—may itself be evidence of how justice functioned (or failed to function) when nobility was involved.

Conclusions

Based on the available evidence, we can conclude:

- Marie Lorgueil demonstrated legal agency. She did not passively accept her husband's murder—she filed suit against a nobleman, an action that required courage and resources.

- Marie made a rational economic decision. Given the uncertainty of legal victory against a fled nobleman, the cost of prolonged litigation, and her immediate financial needs, the settlement offered certain survival over uncertain justice.

- Colonial justice was stratified by class. The ability of a nobleman to murder a habitant and flee without apparent consequence—and the widow's practical inability to pursue justice through normal channels—reveals the power dynamics embedded in the colonial legal system.

- Legal rights could be commodified. The settlement document shows that legal claims were transferable assets that could be bought and sold—creating a mechanism by which wealthy individuals could pursue cases on behalf of those who could not afford to.

- Marie's choice enabled her family's survival. She lived another ten years, surrounded by family, dying at 66 of natural causes—a peaceful end that her pragmatic decision helped make possible.

PART III: SOURCE CITATIONS

Primary Sources

1. Marie Lorgueil Baptism Record (1634)

Parish of Sainte-Croix (Holy Cross), Bordeaux, France. Baptism register, June 15, 1634. Marie, daughter of Pierre d'Orgueil and Marie Bruelle, born June 14, 1634. Archives Bordeaux Métropole, Series GG 205 - Baptism register (June 2, 1633 - December 29, 1644). Research credit: Gilles Brassard, January 16, 2023.

2. Marriage Record (1654)

Notre-Dame de Montréal, Quebec. Marriage register, November 23, 1654. Toussaint Hunault and Marie Lorgueil. Bride's stated age: 16 (actual age: 20). FamilySearch digital images.

3. Census of New France (1666)

Royal Census of New France, 1666. Household of Toussaint Hunault, habitant, Montreal. Family members enumerated: Toussaint (adult), Marie (adult, listed as age 31-32), Thècle (11), André (8), Jeanne (7-8), Pierre (5), Marie-Thérèse (2-3), Mathurin (1). Library and Archives Canada.

4. Notarial Obligation (1683)

Notarial obligation, November 15, 1683. Debtors: Toussaint Hunault and Marie Lorgueil. Creditor: André Hunault (son). Amount: 307 livres. Notarial records, French Regime. BAnQ Montreal.

5. Death Record: Marie-Thérèse Hunault (1689)

Death and burial record, Lachenaie, August 17, 1689. Marie-Thérèse Hunault, wife of Guillaume Leclerc. Cause: Murdered during Iroquois raid on Lachenaie. Age at death: 26 years, 6 months. FamilySearch digital images.

6. Death Record: Toussaint Hunault (1690)

Death record, Montreal area, September 13, 1690. Toussaint Mathurin Hunault dit Deschamps. Cause: Murdered by Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac, Lieutenant of a Company of Marines. Method: Run through with sword. Murderer fled after attack. Peter Gagne research compilation.

7. Widow's Settlement (1691)

Cession de droits (transfer of rights), 1691. Parties: Marie Lorgueil and eight children (sellers) to Charles de Couagne, merchant (buyer). Terms: 520 livres cash payment plus complete dissolution of Toussaint Hunault's debt to Couagne. Rights transferred: All inheritance rights and all rights to damages from lawsuit against Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac. Referenced in Peter Gagne research.

8. Death Record: Marie Lorgueil (1700)

Death and burial record, Varennes, Quebec. November 29-30, 1700. Marie Lorgueil, widow of Toussaint Hunault. Age at death: 66 years. Natural causes. Residing with son André Hunault. FamilySearch digital images.

Secondary Sources

Peter Gagne Research

Research compilation providing leads to widow's settlement document and murder details. Gagne's work provided the initial reference to the 1691 settlement that formed the foundation of this case study.

Gilles Brassard Research

Located Marie's baptism record in Archives Bordeaux Métropole, January 2023. This discovery corrected a 4-year error in Marie's established birth year, enabling accurate calculation of her age at key life events.

Archives Consulted

- Archives Bordeaux Métropole, Bordeaux, France

- Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ), Montreal

- Library and Archives Canada

- FamilySearch (parish registers, digitized images)

- Royal Jurisdiction of Montreal court records

What This Story Reveals

Marie Lorgueil's story is not just about one widow's impossible choice. It is about how justice worked—or did not work—in colonial New France.

When a nobleman killed a habitant, the legal system existed in theory to provide recourse. But in practice, pursuing that recourse required resources most people did not have. Time, money, connections, the ability to wait months or years for an uncertain outcome. The legal system was accessible to those who could afford to access it.

Marie could not afford it. So she sold it.

And in doing so, she revealed something important about colonial power structures: justice was not just blind—it was expensive. And expensive justice is not really justice at all.

But here is what strikes me most about this story: Marie did not give up. Even knowing the odds, even understanding the power differential, she still filed suit. She still demanded that her husband's murderer face consequences. She still used what leverage she had—the case itself—to negotiate the best deal she could.

That is not resignation. That is strategy. That is survival.

Marie's Legacy

Today, Marie Lorgueil has thousands of descendants across North America. They exist because she made hard choices. They exist because when a Baron murdered her husband and fled, she did not collapse—she calculated. She assessed her options. She made a deal. 520 livres for a murdered husband. It is an obscene equation. It is an impossible choice. But it is the choice Marie made. And her family survived.

That is not the justice Marie deserved. But in 1691 New France, it was the justice she could afford.

The Unanswered Question

Somewhere in the archives of New France, there might be records that tell us what happened to Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac. There might be a trial record, a punishment, a transfer order, something that explains whether he ever faced consequences for running Toussaint Hunault through with a sword on September 13, 1690.

Or maybe there is nothing. Maybe he just... got away with it.

If you know anything about Baron de Blaignac's fate, about Charles de Couagne's pursuit of the case, about whether any justice was ever served in this story, I would love to hear from you. Because Marie's story does not end with her choice—it ends with the question of whether that choice mattered.

Did Couagne fight for Toussaint? Did the Baron pay? Or did 520 livres buy Marie's survival while buying the Baron's freedom?

DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE

The documents below trace the tragedy that shaped Marie Lorgueil's final decade—from her daughter's murder in August 1689 through her husband's death thirteen months later, to the settlement that traded justice for survival.

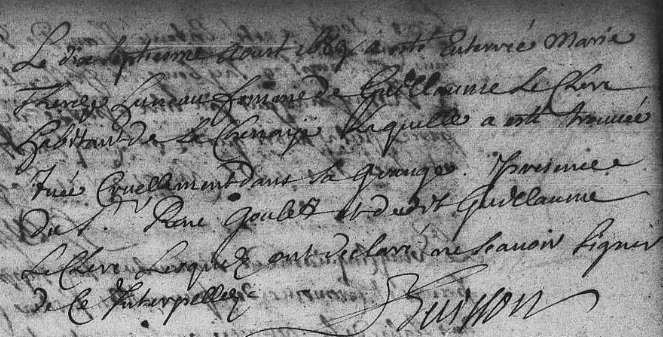

Burial Record: Marie-Thérèse Hunault

"On the seventeenth of August 1689, Marie Thérèze Huneau, wife of Guillaume Le Clerc, resident of La Chenaye, was buried. She had been found cruelly murdered in her barn. René Goulet and Guillaume Le Clerc were present, but both declared they could not sign, having been questioned about this."

Marie-Thérèse was 26 years old, married 13 years to Guillaume Leclerc. The phrase "cruelly murdered in her barn" indicates the violence of the Iroquois raid on Lachenaie. Her husband Guillaume survived—he was present at her burial but could not sign his name.

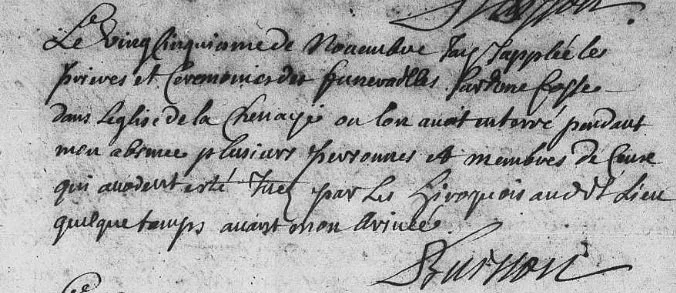

Mass Burial Record: Iroquois Raid Victims

"On the twenty-fifth of November, I took part in the prayers and funeral ceremonies at a grave in the church of La Chenaye where several people and members of those who had been killed by the Hiroquois at the said place some time before my arrival had been buried during my absence."

This mass burial record, written three months after the August raid, documents the community's collective trauma. Marie-Thérèse was among "several people" killed that day. The priest had been absent during the initial burials and returned to conduct proper funeral ceremonies.

Toussaint Hunault: Death and Burial

The Missing Record: Although Toussaint was murdered in Montreal on September 13, 1690, his burial record has not been located. He was likely buried at Saint-Joseph Cemetery (Rivière-des-Prairies) where he lived, but the parish records for that year are missing. The registers of Notre-Dame in Montreal do not contain his burial between his death on September 13 and October 5, 1690.

What we know comes from the 1691 widow's settlement: Toussaint Mathurin Hunault dit Deschamps was "run through with a sword" by Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac, Lieutenant of a Company of Marines. The Baron fled after the attack.

Land Concession: Toussaint and André Hunault

Three years before his murder, Toussaint and his son André received this land concession. This document represents what the Hunault family had built over 33 years in New France—property, stability, a future. All of it was put at risk when the Baron's sword found Toussaint.

Widow's Settlement: Cession de droits

The Terms of the Agreement

What Marie Gave Up: All inheritance rights from Toussaint's estate, plus all rights to any damages that might be won in the lawsuit against Baron de Blaignac. Charles de Couagne, Montreal merchant, acquired the legal case—betting he could pursue the Baron where Marie could not afford to.

The Parties: Marie Lorgueil and her eight children (sellers) transferred their rights to Charles de Couagne (buyer). The absent defendant—Gabriel Dumont, Baron de Blaignac—had fled and his whereabouts remained unknown.

Death Record: Marie Lorgueil

Marie lived ten years after selling her legal rights. She died at age 66 in Varennes, residing with her son André. She had survived everything—the frontier, the loss of two young children, her daughter's murder by Iroquois raiders, her husband's murder by a French nobleman, and the impossible choice that followed. Her family survived with her.

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTERReady to Discover Your Family's Story?

Let's explore your family history together. Schedule a free consultation to discuss your research goals and how we can help bring your ancestors' stories to life.

Schedule Your Free Consultation