Finding the Filles du Roi in Colonial Records

Part of the Storyline Genealogy series: From marriage contracts to baptismal records—the documentary trail of the King's Daughters

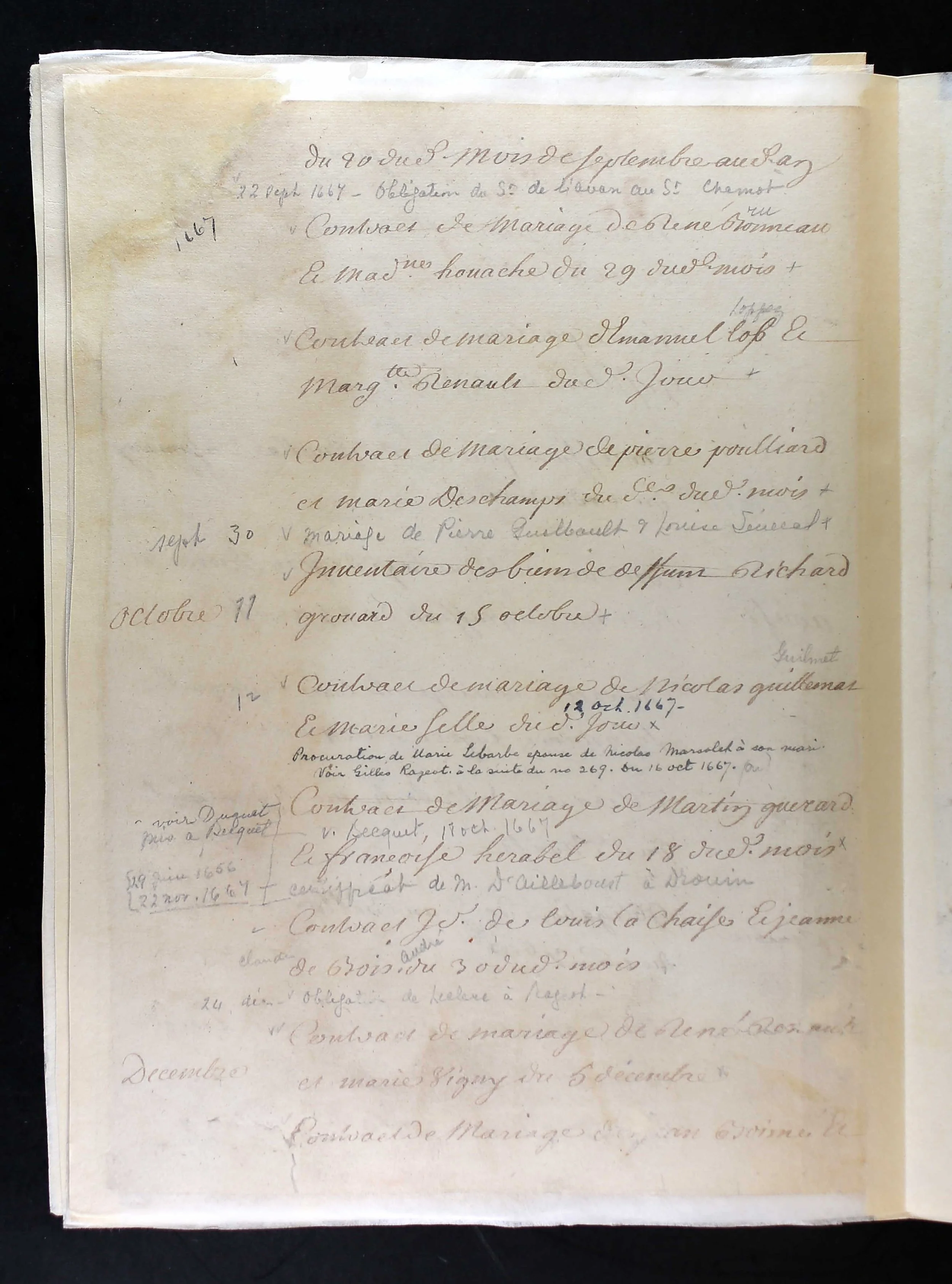

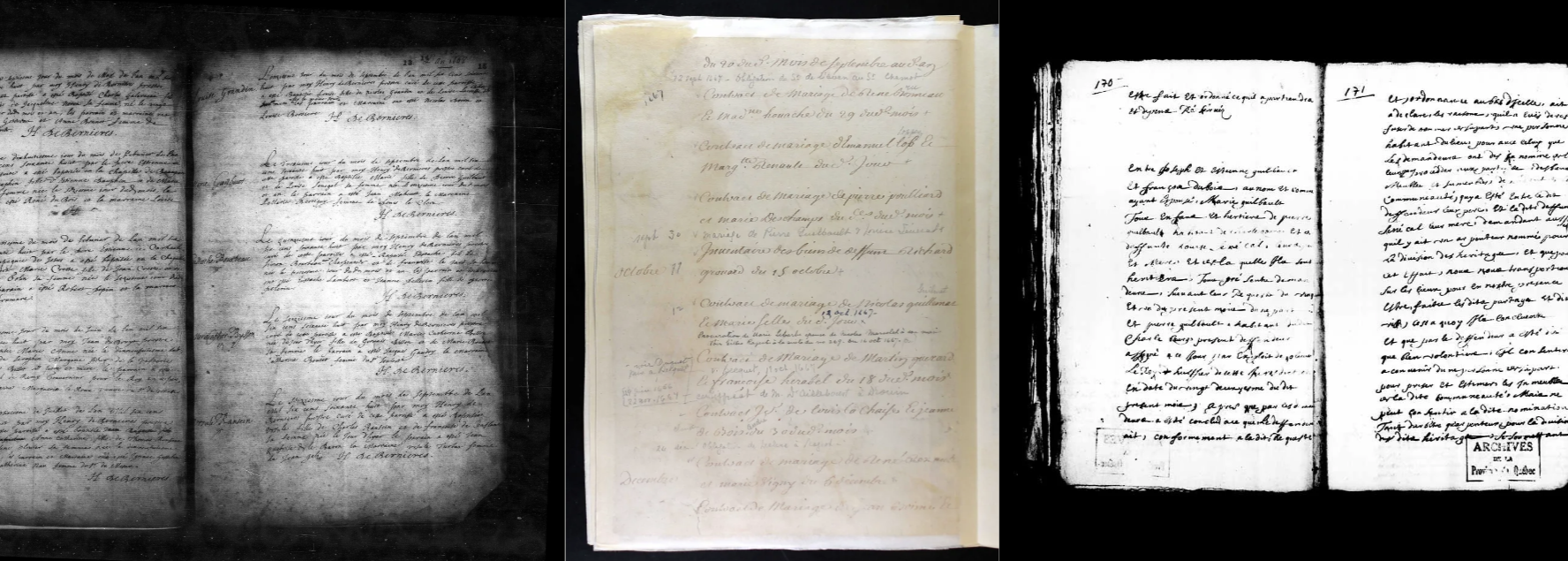

1667 Marriage Contract from New France

When I trace the lives of the Filles du Roi and Filles à Marier—the women who became the founding mothers of French Canada—I'm always aware of what I'm holding in my hands. These aren't personal diaries or letters home to France describing the shock of a Canadian winter or the anxiety of choosing a husband within days of arrival. Instead, I work with something more bureaucratic yet equally revealing: the administrative machinery of colonial life.

The Paper Trail of Colonial Women

The Filles du Roi left a distinctive documentary footprint precisely because they were part of a state-sponsored program between 1663 and 1673. When King Louis XIV decided to address New France's severe gender imbalance, he created a bureaucracy—and bureaucracies keep records. Each woman recruited for the program needed a letter of reference from her parish priest or local magistrate. Her passage was documented. Her royal dowry of 50 livres was recorded. These administrative records often tell us her age, her origins in France, and sometimes hints about her family circumstances.

The Filles à Marier—the "marriageable girls" who arrived before the official program began in 1634 through 1662—left a lighter trail. Without state sponsorship, their recruitment was more informal, often through family connections or religious organizations. For these earlier arrivals, we rely more heavily on what happened after they reached New France.

17th Century Map of France

Where the Stories Live

The richest sources for reconstructing these women's lives in New France are the church registers and notarial archives. Marriage contracts, often notarized within days of a woman's arrival, become miniature biographies. They list parents' names and geographic origins, sometimes describing the bride's circumstances with surprising detail. When seventeen-year-old Marie arrives from Paris and marries a habitant farmer within a week, the contract might tell us she's an orphan, that she brings her small dowry, that her new husband already owns cleared land.

Then come the baptismal records for their children—typically five to seven per woman who survived childbearing years. These records create a timeline of family life, showing where the family settled, who served as godparents (revealing social networks), and sometimes recording tragedies when dates cluster too close together.

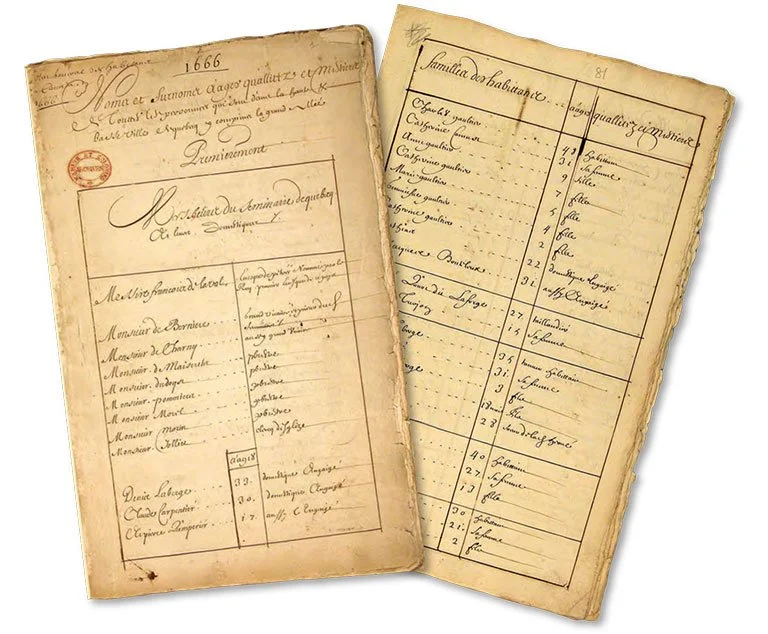

Census data adds another layer. Jean Talon's comprehensive 1666 census, for instance, captures many Filles du Roi in their first years of marriage, documenting household composition, livestock, and cleared acreage. Through sequential censuses, we watch families grow, move, and sometimes disappear.

Pages from the 1666 census of New France.

Library and archives Canada 2318856.

Reading Between the Lines

Court and notarial archives occasionally provide unexpected glimpses into these women's lives. An annulled marriage contract hints at second thoughts. A legal dispute over inheritance reveals family dynamics. A will's provisions suggest which child remained closest or which daughter-in-law earned special regard.

Modern genealogical resources have transformed access to these scattered records. The Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH) database has compiled biographical information on thousands of individuals, linking marriage records to baptisms to burials. Peter J. Gagné's King's Daughters and Founding Mothers provides individual biographies that allow researchers to see patterns: the woman from La Rochelle who married three times as successive husbands succumbed to the harsh conditions, the Paris orphan who raised twelve children and lived to see her grandchildren establish their own farms.

What We Can—and Cannot—Know

The documentary record provides facts: names, dates, family connections, geographic movements. What it rarely provides is interiority—thoughts, feelings, motivations. When we say a woman emigrated seeking a better life or fleeing lack of marriage prospects in France, we're making informed inferences based on historical context rather than reading her own explanation.

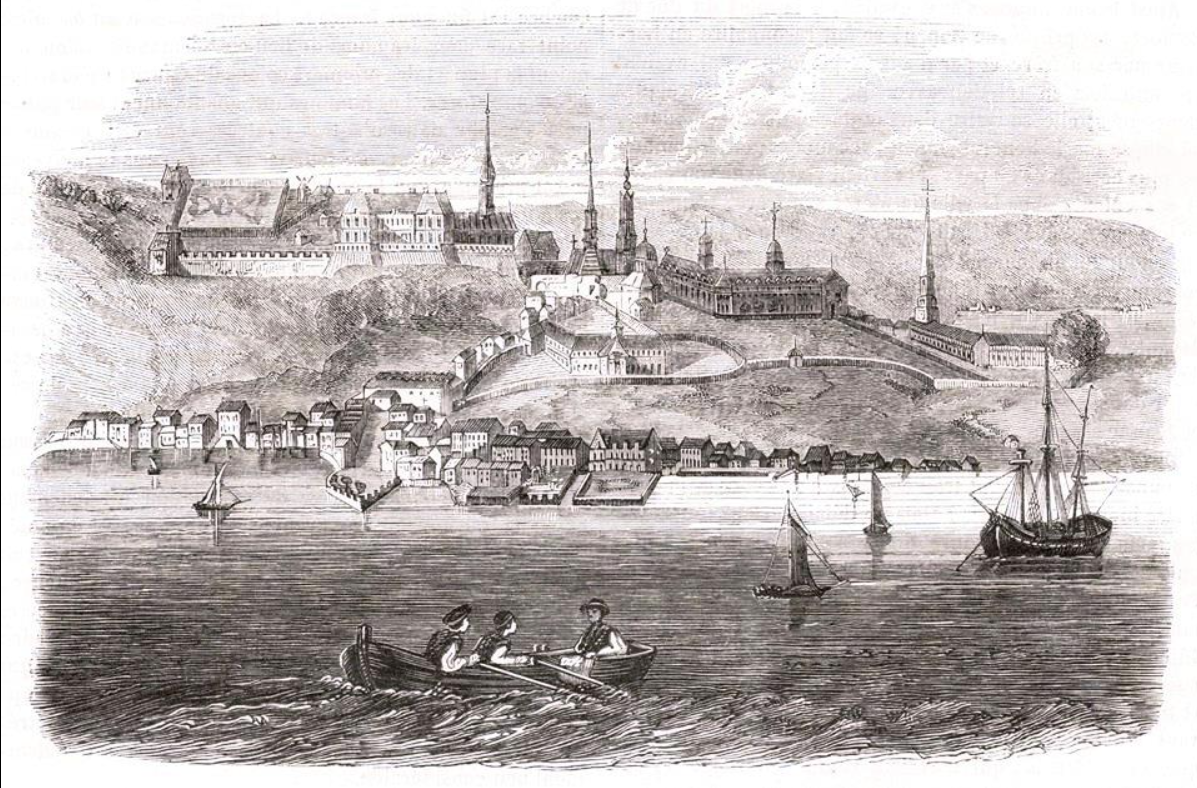

We know from the administrative records that these women had agency in choosing their husbands—a freedom not always available to women of their class in France where marriages were typically arranged. The quick marriages upon arrival weren't coerced but practical responses to the colony's demographics. Yet what did it feel like to stand in a room in Quebec City or Montreal, recently arrived from an Atlantic crossing, and make that choice? The notarial contracts document the decision but not the deliberation.

Romanticized depiction of Quebec City in 1720

Société historique de Québec - «Le Magasin pittoresque», 1843, p. 288.

Similarly, we know from demographic research and historical accounts that these women faced harsh conditions: brutal winters, hard physical labor, isolation, and the ever-present dangers of childbirth in a frontier colony. We can document their children, their land holdings, their years of survival. What we cannot access directly are their strategies for endurance, their private fears, or their moments of satisfaction when a harvest succeeded or a child thrived.

The Genealogical Legacy

The most complete documentation comes not from the women's own lifetimes but from their descendants. The vast majority of French North Americans can trace ancestry to at least one Fille du Roi or Fille à Marier. This extensive genealogical documentation confirms what the colonial administrators intended: these women became, quite literally, the founding mothers of French Canadian society.

For researchers investigating specific individuals, resources like the Fichier Origine website and the Société d'histoire des Filles du Roy provide starting points. These organizations maintain the collective research that transforms isolated documents into connected life stories.

From Records to Story

When I work with these sources, I'm always navigating the gap between what the documents say and what we wish they could tell us. A marriage contract dated three days after a ship's arrival tells me about decision-making under pressure and colonial realities. A series of baptismal records with the same godparents appearing repeatedly reveals friendship networks and mutual support systems. A widow's remarriage within months of her husband's death speaks to economic necessity more than callousness.

The story emerges not from single documents but from the accumulation of evidence, read within historical context. These women left their documentary footprints across colonial New France—in notarial archives, parish registers, census rolls, and court records. While we cannot recover their voices directly, we can trace their actions, their choices, and their profound impact on the society they helped build.

Various document types from New France

For Researchers: The PRDH database (Programme de recherche en démographie historique) provides the most comprehensive digital access to vital records from New France. The Fichier Origine website specializes in tracing French origins of Quebec ancestors. The Société d'histoire des Filles du Roy maintains extensive research on individual King's Daughters and can assist with specific genealogical inquiries.

Have you traced your ancestry to a Fille du Roi or Fille à Marier? What documents helped you piece together her story?

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTERReady to Discover Your Family's Story?

Let's explore your family history together. Schedule a free consultation to discuss your research goals and how we can help bring your ancestors' stories to life.

Schedule Your Free Consultation