The Woman in the Portrait: Aunt Maime’s Story

How We Found Mary F. MacKinney After 90 Years

For 90 years, her portrait sat carefully preserved but unlabeled, passed down through four generations. We knew only that "Aunt Maime was important." In October 2025, we finally discovered who she was—and her story is extraordinary.

The Mystery Portrait

For 90 years, this portrait was carefully preserved in this ornate frame, passed through four generations. The backing paper - a 1920s lipstick color chart - shows it was lovingly remounted during that era. But her name was lost.

She looks out from behind glass in an ornate Art Nouveau frame with decorative pink diamonds. Whoever mounted this portrait decades ago chose beauty, chose preservation, chose to honor her. The frame itself whispers: "This woman is important."

A second portrait—larger, clearer—was also carefully preserved, showing the same woman with quiet dignity, her wire-rimmed glasses, her soft waves of hair.

For decades, family members looked at these portraits and wondered: "Who is she?"

We knew she was important. The photographs were too carefully preserved, the ornate frame too deliberate, the portraits passed down through too many generations to be insignificant. But her name was lost. The details of her life, forgotten. Until October 2025, when death certificates, census records, cemetery archives, and the dedication of family historians finally revealed her complete story.

Her name was Mary F. MacKinney, though the family called her "Aunt Maime." And what we discovered changed everything we thought we knew about our family history.

Part I: Early Loss (1860s-1888)

Mary F. MacKinney was born around 1860-1865 in Brooklyn, New York, to Irish immigrant parents George MacKinney and Ann Lynch MacKinney. Her father George had fled Ireland during the Great Famine, arriving in America around 1847 at just 19 years old. He settled in Brooklyn, working as a laborer, married Ann, and they had at least two daughters: Mary and Margaret.

But tuberculosis—the plague of 19th-century cities—came for their family.

December 31, 1870: Father Dies

When Mary was just 5-10 years old, her father George died of pulmonary tuberculosis at age 42. He had been sick for years. On the last day of 1870, he died on Schank Street near Willoughby in Brooklyn's 7th Ward, leaving behind his widow Ann and young daughters Mary and Margaret.

Ann buried George on January 1, 1871, at Holy Cross Cemetery in Brooklyn. But she didn't just purchase a single grave—she purchased a family plot: Lett Row L, Plot 336. Even in poverty, even as a widow with a young daughter to support, Ann ensured her family would rest together.

Growing Up Without a Father (1870-1887)

For the next 17 years, Mary grew up watching her mother struggle to survive as a widow in immigrant Brooklyn. By 1880, they were living at 367 Kent Avenue. Ann worked to support them both. Mary learned what it meant to persevere.

But in November 1887, Ann suffered a cerebral embolism—a massive stroke. She became bedridden, paralyzed, requiring constant nursing care.

Mary, now in her twenties, became her mother's caregiver.

May 10, 1888: Mother Dies

For six months, from November 1887 to May 1888, Mary nursed her dying mother. Ann never recovered. On May 10, 1888, at their home on 847 Kent Avenue, Ann died at age 66.

Mary was now completely alone. Both parents gone. Her sister gone. No husband. No property beyond what her mother had secured. No children of her own.

She was 23-28 years old, orphaned, and uncertain of her future.

Part II: The Crisis That Changed Everything (November 1888)

Six months after burying her mother, Mary faced a choice that would define the rest of her life.

November 30, 1888: A Brother-in-Law Dies

John Kenny, Mary's brother-in-law through his marriage to her sister, Margaret McKenny Kenny, died of tuberculosis at age 36. He had been widowed four years earlier when his wife Margaret died of the same disease in 1884. Their infant daughter had died three months after Margaret. John's mother had just died in December 1887.

When John died at St. Catharine's Hospital in Brooklyn on November 30, 1888, he left behind two completely orphaned daughters:

Elizabeth M. Kenny, age 9

Mary Agnes Kenny, age 5

Two little girls. No parents. No grandparents. Nowhere to go.

The Decision

Mary F. MacKinney had just spent six months nursing her dying mother. She had just buried Ann in May. She was still grieving. She was unmarried, with no stable income beyond domestic service work. She had no husband to help support additional children.

But she took them in anyway.

Elizabeth, age 9, and Mary Agnes, age 5, came to live with Mary. She became their mother in everything but name.

This decision—made in grief, in poverty, with no guarantee of success—would define the next 47 years of Mary's life.

Part III: Survival and Achievement (1888-1935)

The Desperate Years: Domestic Service (1888-1900s)

To support herself and two orphaned girls, Mary worked as a domestic servant. The Brooklyn Eagle newspaper preserves her desperate search for work:

April 1887 (while still caring for dying mother):

"WANTED—SITUATION—TO DO General housework, by a respectable girl. Please call at No. 847 Kent av."

September 1888 (4 months after mother died, 2 months before John Kenny died):

"WANTED—SITUATION—TO DO GENERAL housework, by a respectable young girl; will be found willing and obliging. Please call for two days at 847 Kent av."

October 1889 (11 months after taking in the orphaned girls):

"WANTED—SITUATION—TO DO GENERAL housework by a respectable strong young girl. Please call at 847 Kent av."

These aren't just advertisements. They're evidence of desperation—a woman seeking any work to feed and house two orphaned children who depended on her completely.

The Climb: Forewoman at a Lace Factory (1910)

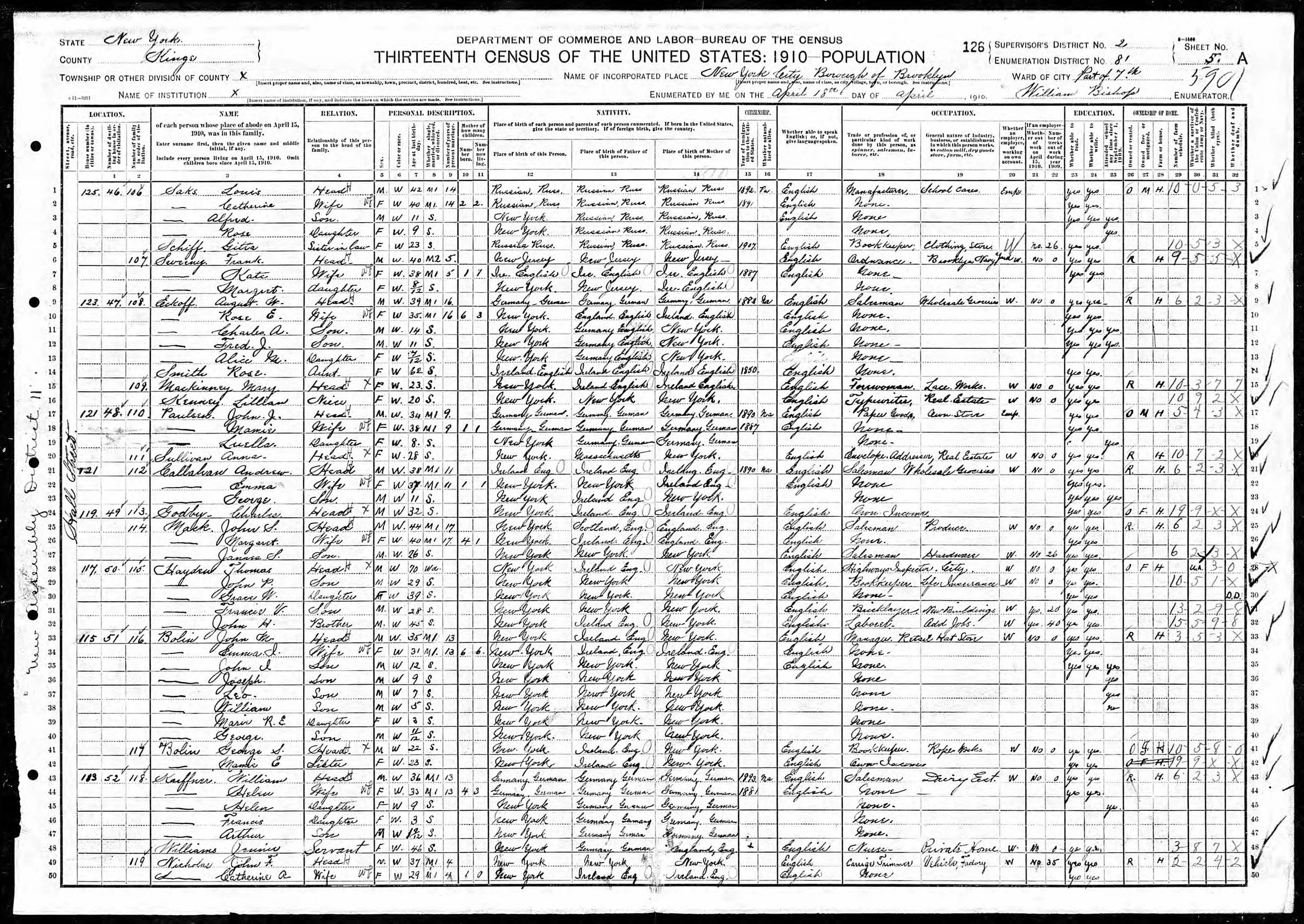

1910 Federal Census showing Mary MacKinney, Forewoman, living at 123 Hall Street with niece Lillian Kenny

By 1910, something remarkable had happened. The 1910 census shows Mary living at 123 Hall Street in Brooklyn's Ward 7, working as a Forewoman at a Lace Works—a factory supervisor, managing other workers, holding a position of authority and skill.

This is extraordinary upward mobility.

She had gone from desperate domestic servant placing ads in newspapers to factory management. She supervised workers. She earned a stable wage. She had achieved something few women of her time and circumstances could claim: economic independence and professional respect.

Living with her: Niece "Lillian Kenny" (actually Elizabeth, called Lillian), age 31. Mary was still supporting the girl she had taken in 22 years earlier.

The Entrepreneur: Boarding House Keeper (1920)

1920 Federal Census showing Mary MacKinney, Keeper Boarding House, living on Avenue N

By 1920, Mary had achieved another level of success. The census shows her living on Avenue N in Brooklyn's Flatbush neighborhood—a better area, more suburban and residential than the tenement districts where she'd started.

Her occupation: Keeper, Boarding House.

She now owned and operated her own business, taking in boarders for income. She had moved from employee to entrepreneur. Living with her: "Lillian Kenny" (Elizabeth), now age 41, working as a Typist at the Navy Yard Supply Department.

Both women had achieved middle-class stability. Both were working professionals. Both had come so far from that desperate November day in 1888 when two orphaned girls had nowhere else to go.

Achievement Recognized (1915-1920s)

Mary F. MacKinney, circa 1915-1920. This professional studio portrait shows her during her years as a lace factory forewoman and boarding house owner—a woman who had climbed from domestic service to middle-class prosperity.

Sometime in the mid-1910s to early 1920s, Mary commissioned a professional studio portrait. This wasn't a quick snapshot—it was an investment, a statement. Professional portraits were for people who had achieved something worth documenting.

The photograph shows a well-dressed woman of means, confident and dignified. This is not the desperate servant of 1889. This is a woman who has built something.

Newspaper social columns from this era mention "Miss Marie MacKinney" taking summer vacations to resort towns—Saugerties, New York; Cape Elizabeth, Maine. She's traveling with her nieces and grand-nieces, enjoying the leisure time and financial stability she has earned.

From domestic servant to boarding house owner. From poverty to prosperity. From survival to success.

All while raising two orphaned girls to adulthood.

Part IV: The Cycle Repeats (January 1924)

Mary Agnes—the 5-year-old girl Mary had taken in back in 1888—had grown up, married Joseph Robertson around 1904, and had three children: Lillian (born 1905), Helen (born 1907), and Joseph Jr. (born January 1920).

By 1924, the Robertsons had moved to Caldwell, New Jersey. Joseph worked as a salesman and manager. Mary Agnes had achieved the stable family life that Mary MacKinney had sacrificed her own chance at marriage to provide.

But tuberculosis came back. And this time, it brought company.

Sunday, January 13, 1924

Joseph Robertson suffered a cerebral hemorrhage at home. He was rushed to Mountainside Hospital.

Monday, January 14, 1924

Joseph died at age 39. His wife Mary Agnes—Mary MacKinney's beloved "daughter," the little 5-year-old girl she'd taken in 36 years earlier—was already dying of tuberculosis. She'd been sick for a year.

Thursday, January 24, 1924

Ten days after her husband died, Mary Agnes Kenny Robertson died of pulmonary tuberculosis at age 40.

Their three children were now orphaned:

Lillian, age 18

Helen, age 17

Joseph Jr., age 4 years old

Mary MacKinney watched it happen all over again. The orphaning. The tuberculosis. The young woman left to raise children alone.

But this time, it was Lillian—Mary Agnes's 18-year-old daughter—who stepped up, just as Mary herself had done 36 years earlier.

Mary, now in her early 60s and dealing with heart disease, supported Lillian from Brooklyn. She traveled to New Jersey for both funerals. She watched the cycle repeat. She provided guidance on how to survive, how to raise siblings, how to keep going when everything seems impossible.

She had shown Lillian the way by living it herself.

Part V: Final Years and Passing (1928-1935)

340 Maple Street: Modern Living

Photo of 340 Maple Street building if available, or description: "4-story apartment building constructed 1931, 36 units, Prospect Lefferts Gardens

By the early 1930s, Mary was living at 340 Maple Street in Brooklyn's Prospect Lefferts Gardens neighborhood. The building had been constructed in 1931—just 4 years old when Mary lived there. It was a modern apartment building representing the final achievement of her remarkable journey: comfortable, middle-class security.

She had come so far from that desperate day in 1889 when she placed her third newspaper ad seeking housework.

April 5, 1935: A Life Complete

On April 5, 1935, at 8:00 AM, Mary F. MacKinney died at home at 340 Maple Street. She was approximately 70-75 years old. The cause was chronic heart disease that she'd been managing since 1928.

Her funeral was held on April 7, 1935, at the New York and Brooklyn Chapel, followed by a Solemn High Mass at the R.C. Church of St. Francis of Assisi, where she had been a regular attendant and member of church societies.

On April 8, 1935, she was buried at Holy Cross Cemetery, Brooklyn, in Lett Row L, Plot 336—the family plot her mother Ann had purchased 65 years earlier in 1870.

She came home. Home to rest with her father George (died 1870), her mother Ann (died 1888), and the Kenny family she had devoted her life to saving.

Her obituary noted she was survived by "several nieces"—the family she had built through choice, through sacrifice, through 47 years of unwavering devotion.

Part VI: How We Know This Story—The Two Lillians

For 90 years after Mary MacKinney's death, her story was lost. The portrait remained, carefully preserved and passed down, but her identity was forgotten.

The story survived because of two women—both named Lillian—who worked for 90 years to preserve evidence they couldn't fully explain.

THE FRAME THAT PRESERVED HER MEMORY

The small portrait of Aunt Maime was mounted in an ornate Art Nouveau frame with decorative pink diamonds—expensive, careful presentation typical of 1910s-1920s professional portrait mounting. This wasn't a casual snapshot stuck in a cheap frame. This was someone saying: "This woman matters. This portrait deserves beauty."

When the backing needed replacing sometime in the 1920s-1930s, whoever was caring for the frame used whatever paper was available: a Glazo Lipstick color chart from a cosmetics store or beauty counter. You can still see the text on the back: "...chart, reproduced here in bl[ack]... ...enable your customers to choose th[e]... ...the correct shade of Glazo Lipsti[ck]..."

This wasn't carelessness—it was preservation during hard times.

Someone valued this portrait enough to carefully remount it with whatever materials they had, even during the Depression years. The frame was passed through four generations—from Mary Agnes Kenny Robertson (who likely had it framed) to Lillian Robertson O'Brien to Lillian Marie O'Brien Ambrosio to Barbara O'Brien Hamall to Mary Hamall Morales—always protected, always treated as important, even after Aunt Maime's name was forgotten.

The frame itself is evidence: She was loved. She was remembered. She mattered.

Lillian Josephine Robertson O'Brien (1905-1991)

Photo of Lillian Josephine Robertson O’Brien

Mary Agnes's daughter Lillian—the 18-year-old who was orphaned in 1924 and raised her younger siblings—became the first keeper of family memory. From 1905 until her death in 1991, she saved:

Death certificates dating back to 1870

Aunt Maime's professional portrait

Newspaper clippings and obituaries

Cemetery records

Family photographs

But she did something even more extraordinary: For 40+ years, from at least the 1950’s until 1991, Lillian paid for perpetual care of the family graves at Holy Cross Cemetery. She maintained the graves of people who died before she was born—George MacKinney (died 35 years before her birth), Margaret McKenny Kenny (died 21 years before her birth), Aunt Maime herself.

She paid to maintain their graves because they were family.

Lillian Marie O'Brien Ambrosio (1928-1995)

Photo of Lillian Marie O'Brien Ambrosio

Lillian's daughter, also named Lillian, continued the work. During her college years in the late 1940s, Lillian Marie spent her weekends visiting cemeteries throughout New York—Holy Cross in Brooklyn, Greenwood Cemetery, Immaculate Conception in New Jersey—documenting graves, copying records by hand, and eventually paying for continued maintenance.

No computers. No internet. Just weekends in graveyards, hand-copying information before it was lost forever.

She created family group sheets, hand-drew family trees, organized everything her mother had saved. When her mother died in 1991, Lillian Marie continued the perpetual care payments for Holy Cross Cemetery Plot 336 until her own death in 1995.

Together, mother and daughter preserved evidence and maintained graves for 90 years.

They couldn't always explain the complete stories—the repeated tragedies and early deaths made it difficult to transmit everything fully to the next generation. But they knew it mattered. They knew the graves must be tended. They knew the documents must survive.

When Lillian Marie died in 1995, her husband Severino protected the archive until his death in 2010, then passed it to Barbara O'Brien Hamall, who kept it safe and passed it to her daughter Mary in 2018.

Part VII: October 2025—She Finally Gets Her Name Back

In October 2025, Mary Hamall Morales looked at the unlabeled portrait one more time. She'd displayed it on a magnetic board alongside other family photos, wondering daily: "Who is she?"

Using the documents the two Lillians had preserved for 90 years, Mary began searching:

Death certificates from the 1870s-1950s

Census records showing addresses and occupations

Newspaper archives documenting the desperate job searches and later social success

A 7-year research project tracking John Kenny through occupational records to connect him to the family

A phone call to Holy Cross Cemetery on October 17, 2025, speaking with Milton, who confirmed: "Yes, Mary F. MacKinney is buried in Lett Row L, Plot 336"

But how did we know these portraits were of Mary F. MacKinney?

The evidence was compelling:

Both portraits showed the same distinctive round wire-rimmed eyeglasses - a nearly diagnostic feature since eyeglasses in that era were expensive, fitted specifically to the individual, and kept for many years

Similar facial features - face shape, nose, mouth, chin, and bone structure all matched

Same dignified expression and serious demeanor

The ages matched - one portrait showing a woman approximately 55-60, the other 60-70, fitting Aunt Maime's timeline perfectly (c.1915-1920 and c.1930-1935)

Found together in Mary Agnes Kenny's collection - the niece Aunt Maime raised from age 5

Careful preservation - one an expensive studio portrait, the other clipped from a newspaper publication and mounted in an expensive Art Nouveau frame , both showing how important she was to the family

The probability that two different people would have identical eyeglasses, similar features, matching ages, and both be preserved in the same family collection was extremely low.

Piece by piece, the story emerged. The orphaned child who became the savior of orphans. The domestic servant who rose to business owner. The woman who sacrificed marriage and children of her own to raise her cousin's daughters. The 47 years of devotion that saved two little girls from an orphanage and gave them the chance to thrive.

After 90 years, she finally got her name back.

Her Legacy

Mary F. "Aunt Maime" MacKinney never married. She never had biological children. But her legacy includes:

Two orphaned girls saved from destitution in 1888

Elizabeth (Lillian) Kenny, who became a Navy Yard typist and married at 41

Mary Agnes Kenny, who married Joseph Robertson and had three children

Lillian Robertson, who repeated Aunt Maime's sacrifice in 1924, raising her own orphaned siblings

Four generations of descendants who exist because Mary said yes in 1888

90 years of careful preservation by two Lillians who never forgot she was important

A family plot maintained for 70+ years because family matters

This story, finally told

She is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery, Brooklyn, in Lett Row L, Plot 336, alongside:

Her father George MacKinney (died 1870)

Her mother Ann MacKinney (died 1888)

Margaret McKenny Kenny (died 1884)

Baby Margaret Kenny (died 1884)

John Corbett (died 1949)

Elizabeth Kenny Corbett (died 1950)

Seven people spanning 79 years (1871-1950), resting together in the plot Ann MacKinney purchased to keep her family united.

What This Story Teaches Us

Mary F. MacKinney's story reminds us:

About Sacrifice: She gave up her own chance at marriage and children to save two orphaned girls. That choice defined 47 years of her life—and she never wavered.

About Resilience: From desperate newspaper ads to factory forewoman to boarding house owner, she climbed from poverty to prosperity through determination and hard work.

About Family: Family isn't just biology. It's choice. It's showing up. It's taking in two little girls when you have nothing to give except your willingness to try.

About Preservation: The two Lillians saved this story by saving documents and maintaining graves for 90 years. They couldn't tell the complete story themselves, but they ensured someone eventually could.

About Identity: For 90 years she was "an unknown woman." Now she has her name back, and her story will never be forgotten again.

The Woman in the Portrait

Collection of framed family photos on piano, with Aunt Maime's portrait in center, surrounded by photos of Lillian and Helen Robertson (1909), Mary Agnes Kenny (c.1895), and Barbara's wedding photo

The Woman in the Portrait - Surrounded by Her Legacy

Aunt Maime's portrait, displayed on the piano that grandfather gave to Barbara when she was 10 years old, surrounded by the family she created through her sacrifice: Mary Agnes Kenny (c.1895) - the 5-year-old orphan she took in; Lillian and Helen Robertson (1909) - Mary Agnes's daughters; and Barbara's wedding photo in the background - Mary Agnes's granddaughter, who preserved the archive for 18 years before passing it to her daughter Mary, knowing it would be used for research.

Look at her now, knowing who she is.

Look at her surrounded by the family that exists because of her.

This is Mary F. "Aunt Maime" MacKinney (c.1860-1935).

This is the woman who took in two orphaned girls in 1888 when she had nothing.

This is the woman who placed desperate ads seeking housework to feed those children.

This is the woman who climbed from domestic service to factory forewoman to business owner.

This is the woman who achieved middle-class prosperity while raising someone else's children.

This is the woman who watched the cycle repeat in 1924 and guided the next generation through it.

This is the woman two other Lillians honored by preserving evidence and maintaining graves for 90 years.

This is the woman whose story was lost for 90 years and has finally been restored.

This is Aunt Maime. And she was important.

She sits now where she always belonged - in the center of her family, surrounded by four generations of descendants who exist because on one November day in 1888, an orphaned young woman said yes to two little girls who had nowhere else to go.

Read “Four Words That Solved A Mystery” - Discover how 'Kenny, Elizabeth, wid. Richard' unlocked the impossible genealogical puzzle that connected these families.

Read “Four Generations in Hats: A Brooklyn Story of Resilience”- When one craftsman's legacy becomes four generations of resilience—the stories objects can tell.

Read “The Tintype in the Box: Solving a 150 Year Old Family Mystery”-How a nameless Victorian photograph finally revealed its secret

Read “When One Breakthrough Unlocks Everything”-A Storyline Genealogy Case Study in Cascade Research

Read “Occupational Tracking: When Name Searches Fail”-A lesson in using career progression as unique identifiers when traditional genealogy methods reach their limits

Explore the Case Study : The Brooklyn Mat Maker - One occupational progression that unlocked a complete Irish immigrant family story spanning three generations.

Research compiled October 2025 by Mary Hamall Morales using archives preserved 1905-1995 by Lillian Josephine Robertson O'Brien and Lillian Marie O'Brien Ambrosio. Cemetery records verified directly with Holy Cross Cemetery, Brooklyn, October 17, 2025. The John Kenny identification breakthrough achieved through 7-year occupational tracking research project (2018-2025).

For questions or additional family information, contact: mary@storylinegenealogy.com

Part of the Storyline Genealogy Series - Uncovering the Stories Behind the Names

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY