The Tamayo Family

Breaking Through Philippine Research Barriers with Modern Technology

How FamilySearch's new Full Text Search uncovered a multi-generational family saga spanning three decades in rural Philippines

Why Philippine Records Are So Difficult to Find

Philippine genealogy presents unique obstacles that frustrate even experienced researchers. The archipelago's complex history of colonization, warfare, and natural disasters has created a perfect storm of record destruction that makes family research extraordinarily challenging.

The World War II Catastrophe

The single greatest blow to Philippine genealogical records came during World War II, particularly the Battle of Manila in 1945. At least 100,000 Filipino civilians were killed, and the city became "one of the most devastated capital cities of the Second World War, alongside Berlin and Warsaw." More than 11,000 buildings were leveled, along with countless cultural artifacts, historical archives, paintings, and priceless documents.

Many civil records were destroyed during World War II, as Japanese forces systematically demolished buildings and military installations during their retreat. The chaos of war led to the displacement of many families, and many records were lost during this time, creating massive gaps in the genealogical record that persist today.

Colonial Period Disruptions

The Philippines' complex colonial history created multiple layers of record-keeping systems that were often disrupted or abandoned:

Spanish Period (1565-1898)

Catholic Church records, including baptisms, marriages, and deaths, became a primary source of genealogical information. These records, often written in Spanish, offer a wealth of details about individuals and families. However, many of these parish records were lost during wars and natural disasters.

American Period (1898-1946)

The American administration introduced civil registration, creating additional records such as birth, marriage, and death certificates. In 1930, civil registration became mandatory. In 1932 the Bureau of Census and Statistics was created to oversee civil registration. This new system created duplicate record-keeping between local and national levels.

Japanese Occupation (1942-1945)

The Japanese occupation during World War II disrupted record-keeping practices, and many records were lost or destroyed during this time.

Ongoing Natural Disasters

The Philippines' location makes it one of the world's most disaster-prone countries, continuously threatening genealogical records:

Geographic Vulnerability

- Typhoon Frequency: Located along the typhoon belt in the Pacific, the Philippines is visited by an average of 20 typhoons every year, five of which are destructive

- Recent Example: Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) in 2013 killed more than 6,000 people and displaced 600,000 more, with total damages of ₱95.5 billion

- Multiple Hazards: High susceptibility to tsunami, sea level rise, storm surges, landslides, floods, and drought—all threatening archival preservation

Limited Digitization and Access

Unlike European or North American records, Philippine genealogical materials suffer from:

- Sparse online presence: Traditional genealogy databases contain minimal Philippine records

- Language barriers: Records in Spanish, Filipino, and various regional dialects

- Geographic isolation: Many records remain in local archives with limited access

- Infrastructure challenges: Limited resources for digitization and preservation

The Research Desert

The Tamayo family of Numancia, Aklan and Capiz exemplified these challenges perfectly. Despite clear evidence of their existence through property ownership and family memories, their paper trail had gone cold in traditional genealogy databases. Ancestry.com contained sparse Philippine records. MyHeritage offered fragments. Even FamilySearch, with its extensive international collections, seemed to hold little promise for rural Capiz province research.

The Immigration Connection: A Research Lifeline

Ironically, the best initial records for the Tamayo family weren't found in the Philippines at all, but in the United States. Corazon Roldan Tamayo's immigration to America created a paper trail that became accessible through US genealogy databases:

- U.S., Index to Public Records, 1994-2019

- U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007

- U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014

These American records provided crucial information about Corazon that could then be traced back to her Philippine origins. Her marriage to Jose Tamayo, documented in US immigration files, became the key that unlocked the entire family history.

For many Filipino families, the immigration journey of one family member creates the only reliable documented connection to their ancestral homeland. Without Corazon's move to America, the Tamayo family story might have remained forever lost in the Philippine research desert.

FamilySearch Full Text Search

In 2024, FamilySearch launched Full Text Search in beta mode—a revolutionary tool that searches the actual text content within digitized documents rather than just indexed names and dates. This technology promised to unlock millions of previously unsearchable records hidden within document images.

The Test Query

I decided to test this new capability with a simple query:

The results were extraordinary.

A Multi-Generational Family Saga

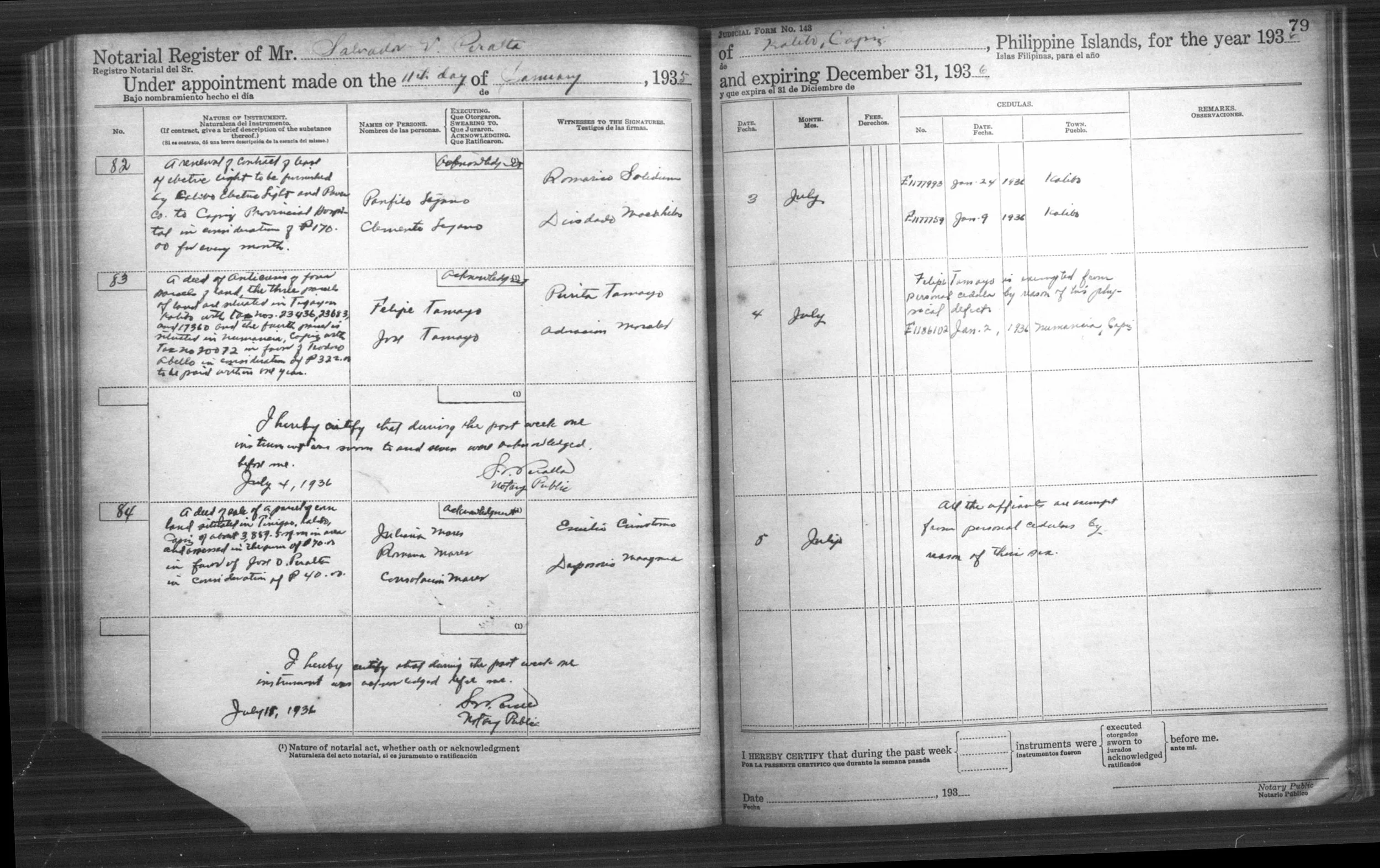

The Full Text Search revealed a treasure trove of property records spanning 1936-1963, documenting multiple generations of the Tamayo family's financial journey and establishing crucial family relationships that had been completely invisible in traditional genealogy databases.

1936 Residence Certificate Felipe Tamayo January 2, 1936, Numancia, Capiz - Felipe Tamayo's residence certificate noting his exemption from personal cédulas due to physical defects, providing rare documentation of colonial-era disability accommodations

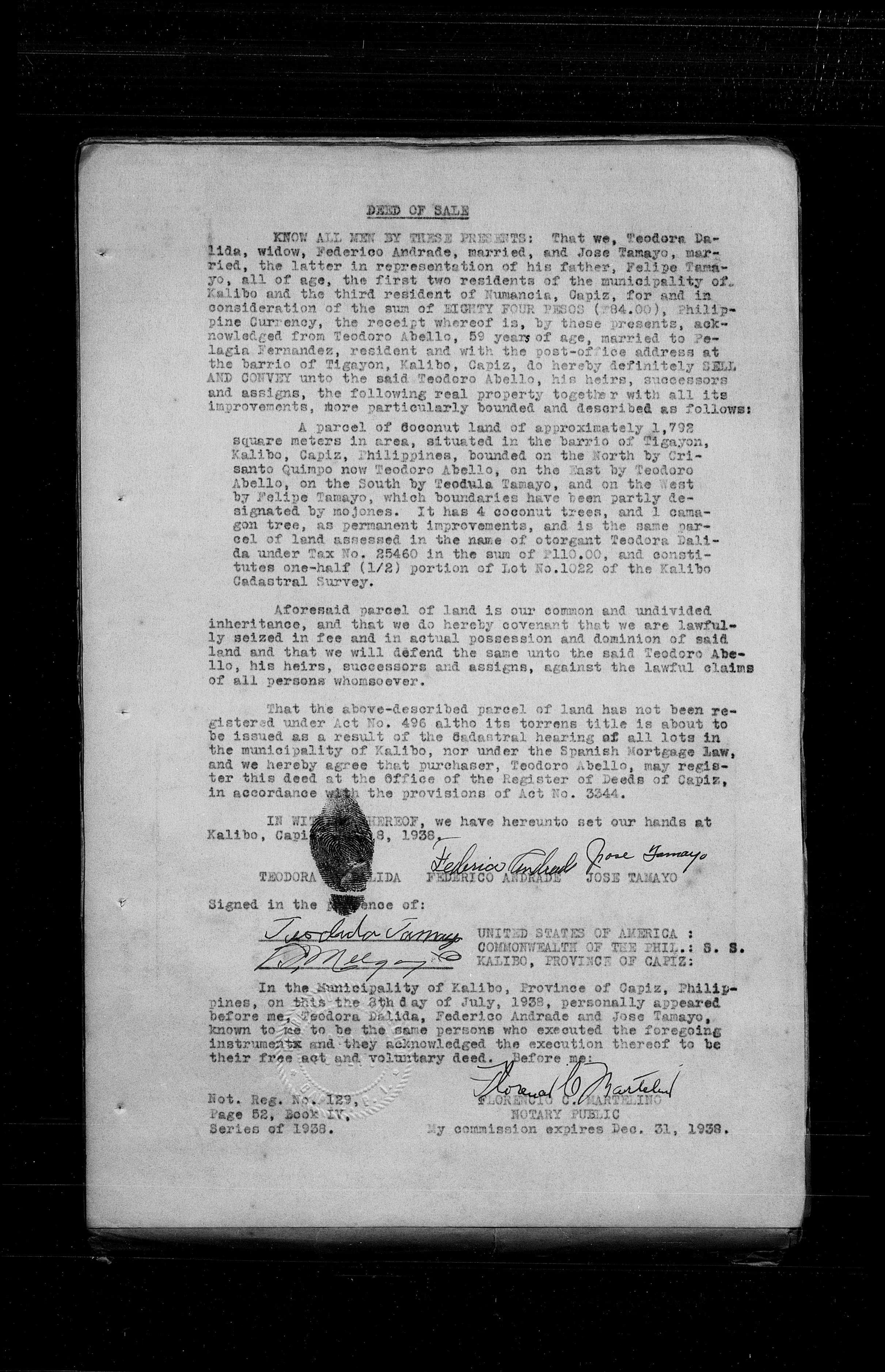

1938 Deed of Sale Coconut Land July 8, 1938 - Documentation of Felipe Tamayo's death and the transfer of coconut land, establishing the foundation of the family's agricultural wealth

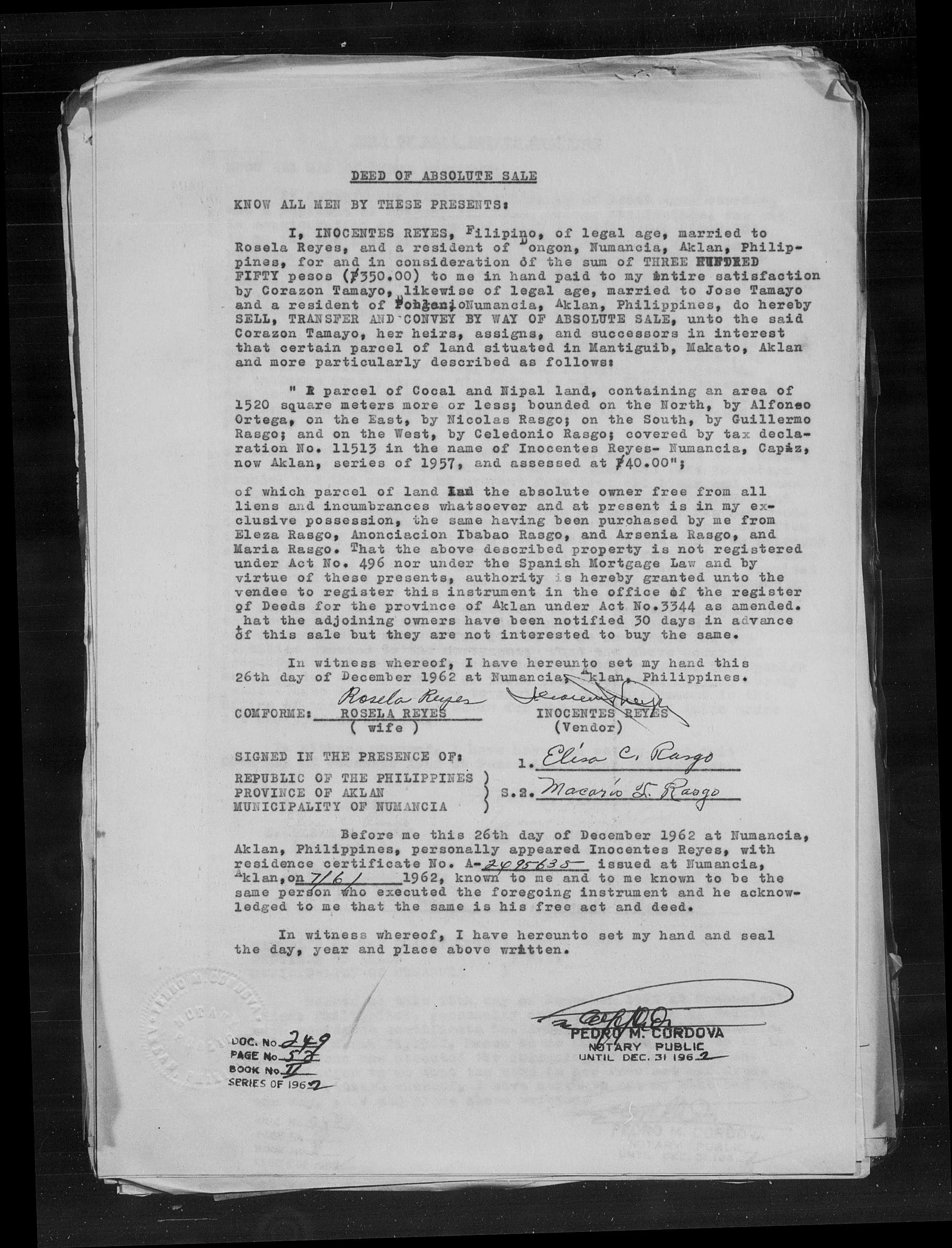

1938 Deed of Sale and Quitclaim July 8, 1938 - Legal document establishing Jose Tamayo's marriage to Corazon Roldan and identifying Purita Tamayo and widow Natividad Icamina, crucial for mapping family relationships

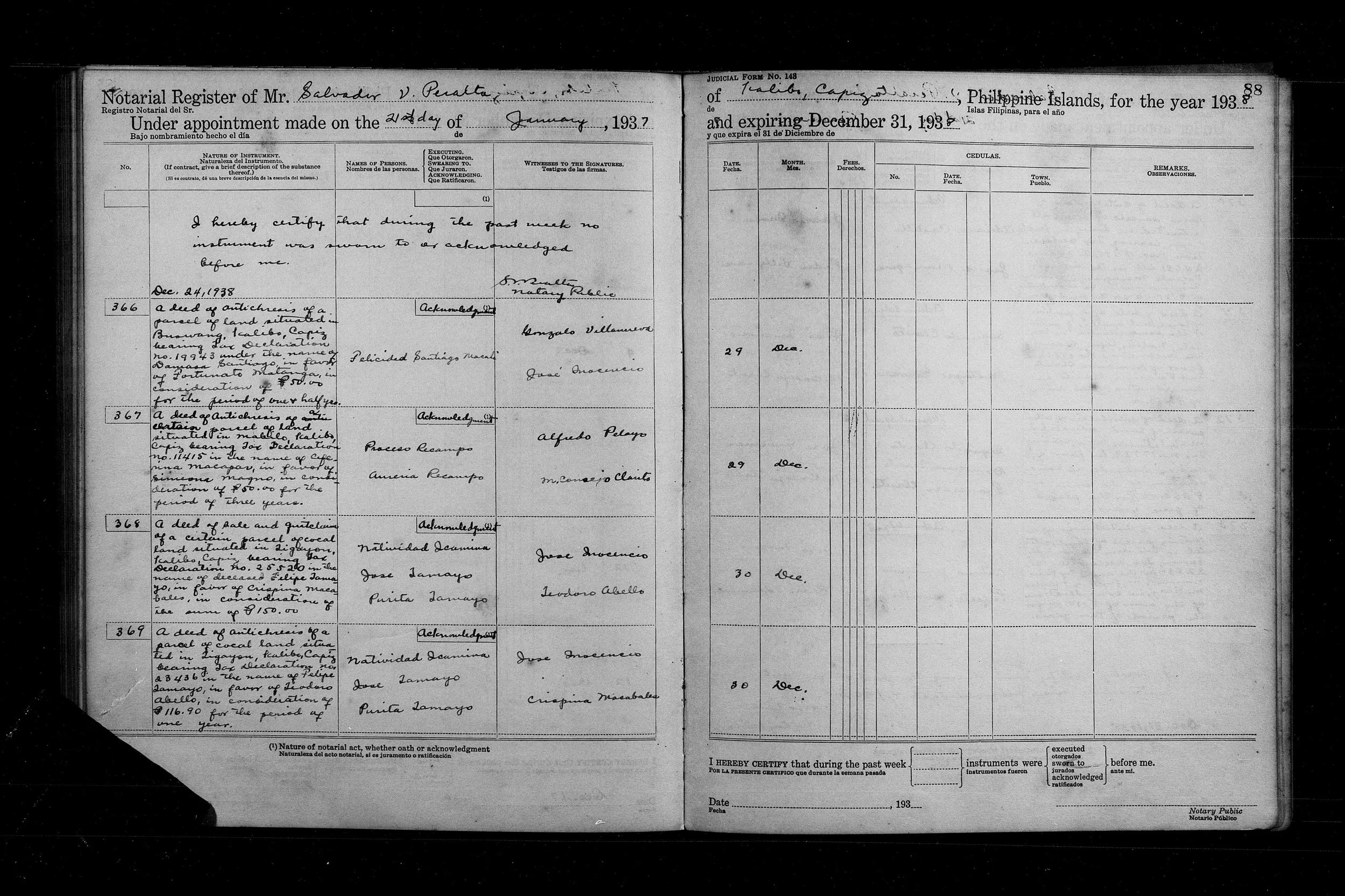

1962 Antichresis Agreement January 28, 1962 - Jose Tamayo's strategic use of inherited coconut land in Tigayon, Kalibo, Capiz as collateral for ₱300 loan, demonstrating sophisticated property management

1962 Antichresis Agreement January 28, 1962 - Jose Tamayo's strategic use of inherited coconut land in Tigayon, Kalibo, Capiz as collateral for ₱300 loan, demonstrating sophisticated property management

1963 Real Estate Mortgage 1963 - Jose and Corazon Tamayo's accumulated substantial agricultural property used as collateral, showing successful multi-generational wealth building

Tamayo Family Residence 1970s - Mr. & Mrs. Jose Tamayo's residence in Numancia, Aklan - physical evidence of the family's prosperity achieved through strategic property management spanning three decades

Timeline of Discovery

Felipe Tamayo's Circumstances

January 2, 1936: Residence Certificate reveals Felipe Tamayo was "exempted from personal cédulas by reason of his physical defects," indicating he had some kind of physical disability or health condition that exempted him from normal civic requirements.

This document provides rare insight into how colonial administrative systems accommodated citizens with disabilities.

Felipe's Death and Family Inheritance

July 8, 1938: Deed of Sale documents Felipe Tamayo's death and the complex transfer of coconut land to his heirs, showing how Philippine inheritance law functioned during the American colonial period.

- Family relationships established: The deed reveals that Jose Tamayo married Corazon Roldan and identifies Purita Tamayo as another family member involved in the inheritance

- Widow identified: Natividad Icamina is revealed as Felipe Tamayo's widow, establishing the maternal line of the family

Strategic Property Management Across Generations

January 28, 1962: Antichresis agreement shows Jose Tamayo using inherited coconut land in Tigayon, Kalibo, Capiz as collateral for a ₱300 loan.

- Parties involved: The complex transaction includes grantors Natividad Icamina (Felipe's widow), Jose Tamayo, and Purita Tamayo, demonstrating how property remained within extended family networks

- Agricultural focus: The shift from residential to agricultural property shows the family's evolution toward farming-based wealth

Accumulated Prosperity

1963: Real Estate Mortgage documents show Jose and Corazon Tamayo had accumulated substantial agricultural property by this time, which they used as collateral for further financial leverage, indicating successful multi-generational wealth building.

Understanding Philippine Legal Instruments

Residence Certificates (Cédulas)

Required identification documents during the American colonial period that tracked citizens for tax and civic purposes. Exemptions for physical disabilities provide rare documentation of how colonial administrations accommodated citizens with health conditions.

Deed of Sale with Inheritance Elements

Complex documents that combine property transfer with family relationship documentation, often serving as unofficial family records when church records are unavailable.

Antichresis Agreement

A contract where real property serves as security for a debt, with the creditor entitled to the fruits/income of the property. The debtor retains ownership while the creditor manages the property until the debt is satisfied. This instrument was particularly common in agricultural regions where coconut and rice harvests provided ongoing income.

Geographic Context

The properties span multiple locations in Capiz province:

- Numancia, Aklan (now separate from Capiz): Town center activities and residential property

- Tigayon, Kalibo, Capiz: Agricultural coconut lands for income generation

- Various parcels: Showing a diversified property portfolio across the region

This geographic distribution reflects smart risk management—diversifying holdings across different municipalities and property types.

Multi-Generational Wealth Building

The documents reveal a sophisticated approach to wealth preservation and growth:

The Family Strategy

The family's strategy of maintaining agricultural land while using it for financial leverage proved successful across changing political periods (Spanish colonial → American colonial → Philippine independence).

Connected Family Lines

This breakthrough in Tamayo documentation opened new research avenues for connected family lines:

The Morales Connection

Property records revealed connections to the Morales family through marriage and witness signatures, leading to discoveries about Mamerto Morales and his tragic wartime story.

Cross-referencing Strategy

Finding one family's detailed records often provides clues for researching related families in the same geographic area and time period. The Tamayo property records included witness names and neighboring property owners that became valuable leads for other family lines.

For Philippine Genealogy Research

- Embrace New Technology: FamilySearch's Full Text Search represents a paradigm shift in genealogical research. Traditional name-based searching missed these records entirely because they were buried within property descriptions, legal language, and witness lists.

- Understand Historical Context: The Tamayo family's activities occurred during significant transitions in Philippine history—the end of American colonial administration, World War II disruption, and the establishment of Philippine independence. Each period created different types of records with varying survival rates.

- Follow Multi-Generational Patterns: These property records revealed character, decision-making patterns, and family values across generations. Felipe's establishment of land holdings despite physical challenges, and Jose's strategic expansion of those holdings, speaks to consistent family planning and agricultural business acumen.

- Combine Multiple Research Approaches: The integration of property records with geographic analysis and family network mapping created a comprehensive family portrait impossible to achieve through any single method.

- Follow the Network: Use discovered records to research connected families in the same area and time period. The Tamayo records included multiple family names that became starting points for other genealogical investigations.

Research Recommendations

For families researching Philippine ancestry, particularly in rural provinces:

- Utilize FamilySearch Full Text Search: Search for surnames combined with specific provinces or municipalities

- Investigate property records: Land transactions often survive when other records are lost

- Understand legal terminology: Familiarize yourself with Spanish and American colonial legal instruments

- Map geographical changes: Provincial and municipal boundaries shifted frequently (note Aklan's separation from Capiz)

- Follow the Network: Use discovered records to research connected families in the same area and time period

From Research Desert to Rich Family History

What began as scattered fragments in US immigration records has become a rich multi-generational narrative of adaptation, strategic thinking, and sustained prosperity. The Tamayo family story illustrates how agricultural families navigated changing political systems while building lasting wealth through land ownership and strategic property management.

More importantly, this case demonstrates that Philippine genealogy—often dismissed as too difficult or incomplete—can yield extraordinary results when approached with the right tools and methodology.

The Tamayo family's journey from Felipe's disability accommodations in 1936 to Jose and Corazon's accumulated prosperity in the 1960s mirrors the broader Philippine experience of adaptation and growth through political transition. Their story, preserved in legal documents and uncovered through innovative search techniques, stands as testament to both individual perseverance and the power of modern genealogical research.

The beautiful family home in Numancia, Aklan—captured in photographs from the 1970s—represents not just individual success, but the culmination of multi-generational strategic planning that began with Felipe Tamayo's initial land acquisitions despite his physical challenges.

Learn More

Ready to Uncover Your Family's Hidden Story?

The Tamayo case demonstrates that breakthrough discoveries are possible when you combine traditional genealogical expertise with cutting-edge technology.

Schedule Free Consultation Explore Philippine ResearchWant to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY