The Widow Who Never Lost: Marie Chapelier's Legal Victory

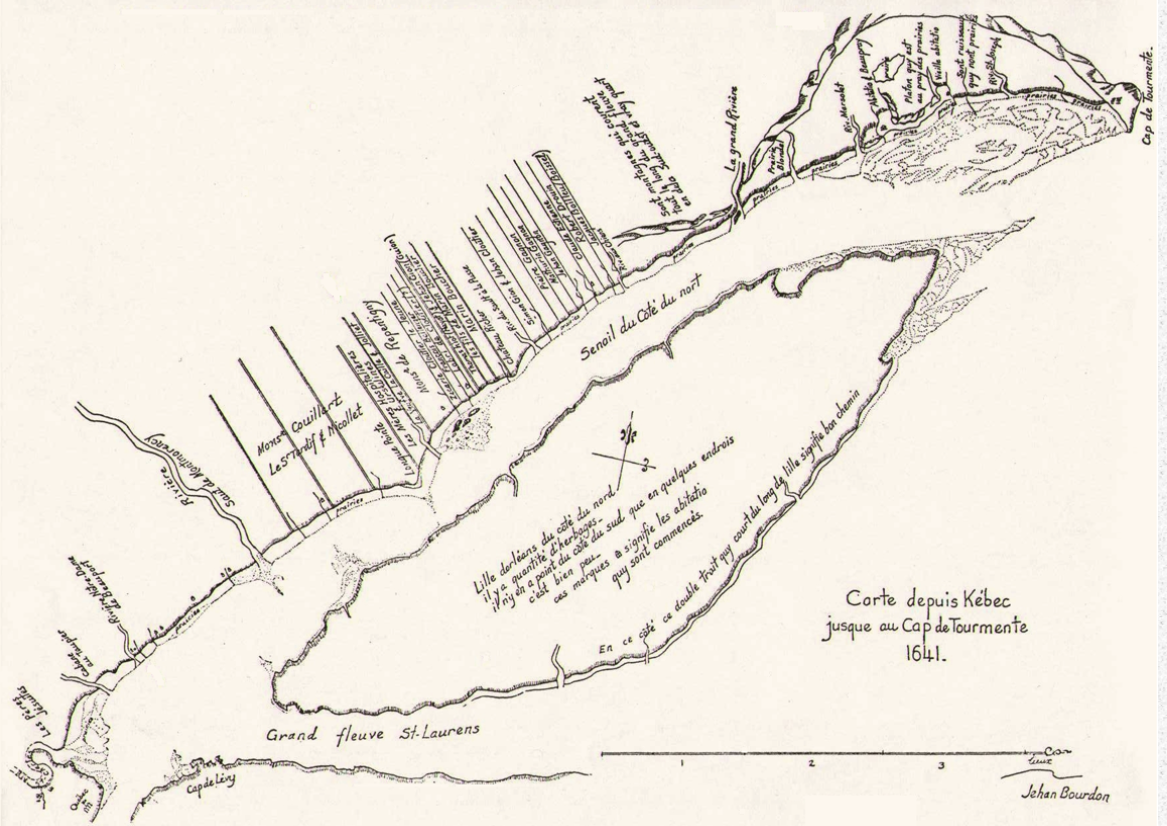

In 1641, the surveyor, Jean Bourdon, drew a map of the Beaupré Coast on which we can locate the land of Robert Drouin. It was situated between the properties of Jacques Boissel and Claude Estienne, to the west of Rivière-aux-Chiens.

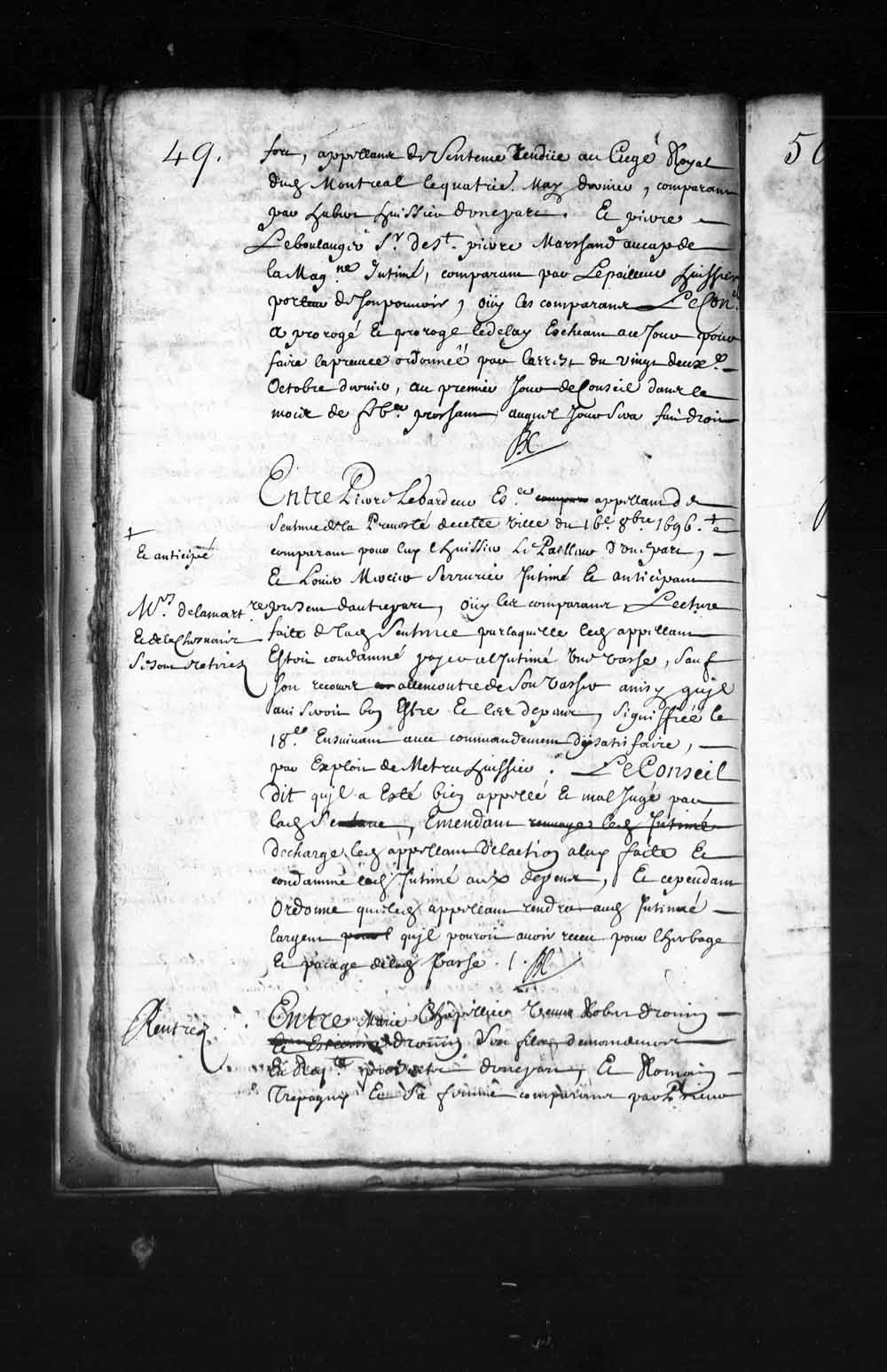

December 4, 1696 — The Final Judgment

The winter air was cold in Quebec City as the Sovereign Council of New France convened for what would be the final chapter in one of the longest civil disputes in the colony's history. At the center of the proceedings sat Marie Chapelier, a 71-year-old widow who had spent the last four years fighting for her rights. Across from her: Romain Trépagny and his wife Geneviève Drouin—Marie's own stepdaughter.

This was the ninth time these parties had appeared before a court. Marie Chapelier had won every single judgment.

The councilors deliberated briefly. The decision was swift and final: Appeal dismissed. Costs to be paid by the appellant.

Marie Chapelier had won again. Three months later, she would die—victorious, undefeated, and having secured her legacy through the most powerful legal system in New France.

This is her story.

The Woman Who Could Sign Her Name

France to New France: A Strategic Journey

Marie Chapelier was born around 1625-1626 in the parish of Saint-Étienne (or Saint-Éloi) in Brie-Comte-Robert, a small town in the Brie region southeast of Paris. Her parents, Jean Chapelier and Marie Dodier, died before she reached adulthood, leaving her an orphan in her early twenties.

Little is known about her first marriage to Pierre Petit, which took place in France sometime before 1649. What we do know is that Pierre died, leaving Marie a widow. In 1649, at approximately age 24, Marie made a decision that would change her life: she boarded a ship to New France.

She arrived in Quebec as a fille à marier—a marriageable woman—seeking a new life in a colony desperate for wives and mothers. Unlike the famous Filles du Roi (King's Daughters) who would arrive two decades later with royal dowries, Marie came on her own terms, with her own resources, and with one crucial advantage: she could read and write.

The Strategic Marriage Contract

On November 26, 1649, Marie Chapelier stood before Guillaume Audouart—the first official notary of New France—to sign her marriage contract with Robert Drouin, a widowed brickmaker from Mortagne au Perche. The document itself is believed to be one of the oldest marriage contracts in Canadian history.

But what makes this contract remarkable isn't just its age. It's what Marie negotiated.

The Signature That Changed Everything

She signed the contract. Robert made his mark with an X. In an era when most women were illiterate, Marie's ability to read and write gave her a powerful advantage. She understood exactly what she was agreeing to—and what she was demanding.

The contract included an unusual clause: Robert Drouin was required to move the couple closer to Quebec City within one year. Marie, sources tell us, had "a holy horror of the countryside." She refused to live in isolation at Rivière-aux-Chiens, where Robert's land holdings were located. She wanted proximity to civilization, to the church, to community.

Robert agreed to her terms.

Three days later, on November 29, 1649, they married at Notre-Dame-de-Québec. Among the witnesses was Marie's cousin, Robert Hache, a Jesuit clerk—a connection that would prove valuable in the years to come.

On November 26, 1649, Marie Chapelier stood before Guillaume Audouart—the first official notary of New France—to sign her marriage contract with Robert Drouin, a widowed brickmaker from Mortagne au Perche. The document itself is believed to be one of the oldest marriage contracts in Canadian history.

Building a Property Empire

The Blended Family Challenge

When Marie married Robert Drouin, she became stepmother to two young girls: Geneviève (age 6) and Jeanne (age 3), daughters of Robert's first wife, Anne Cloutier. Anne had died sometime between 1646 and 1649, after losing four infants in succession. Only Geneviève and Jeanne survived.

The relationship between Marie and her stepdaughters was troubled from the start. Anne's father, Zacharie Cloutier—a prominent figure in the colony—deeply distrusted Marie. He intervened to take custody of his granddaughters, fearing Marie would mistreat them.

This early family conflict would echo forty years later in the courts of New France.

Strategic Property Acquisition

Despite family tensions, Marie and Robert thrived. Between 1649 and 1655, they acquired multiple properties:

1. Cap-de-la-Madeleine Land (1650) Through her cousin Robert Hache's influence with the Jesuits, Marie secured a land grant of 2 arpents river frontage by 20 arpents depth at Cap-de-la-Madeleine. This fulfilled her goal of living closer to Quebec City rather than in the isolated countryside.

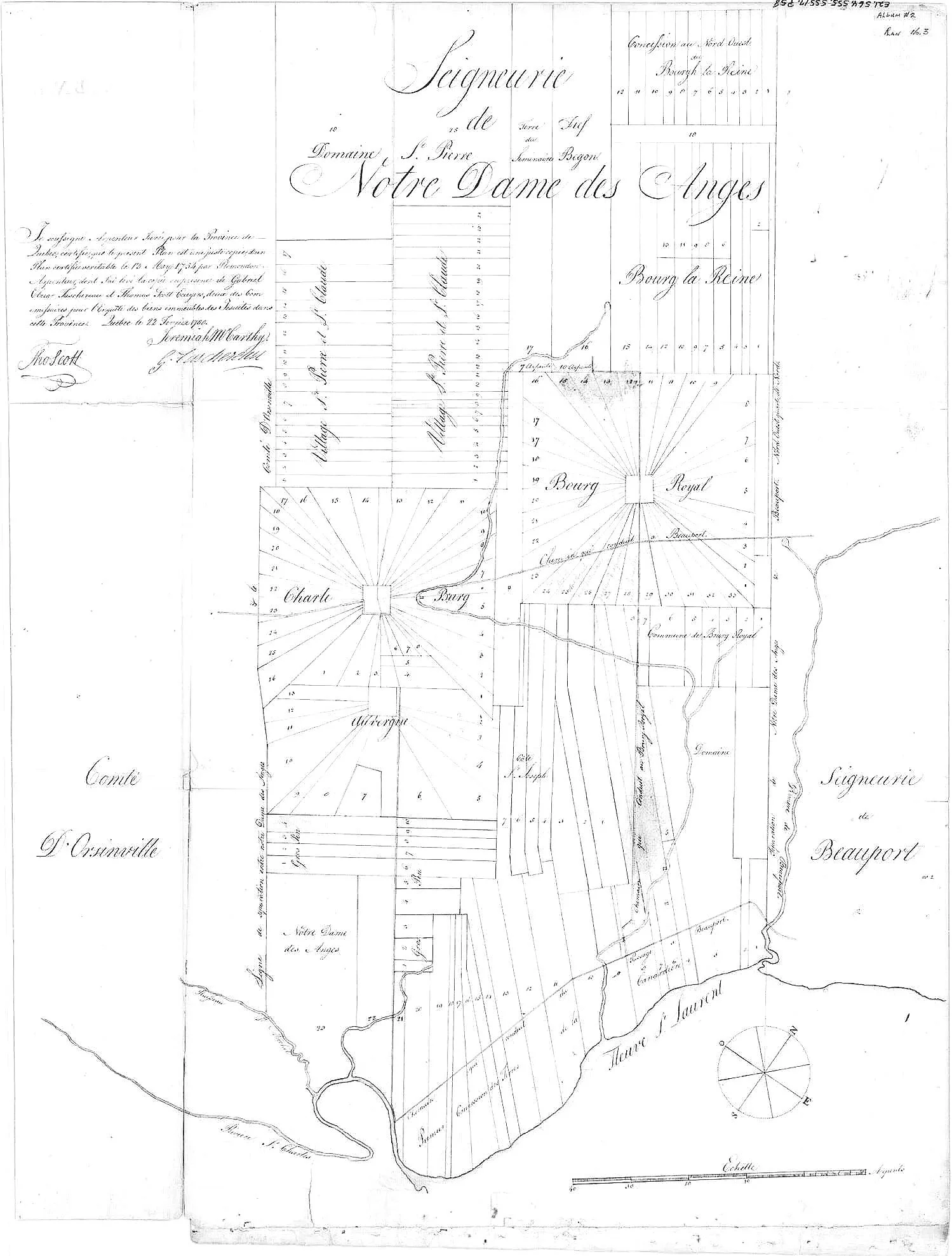

2. Notre-Dame-des-Anges Property (c. 1650-1655) The couple acquired approximately 60 arpents of land with a habitation at Notre-Dame-des-Anges—even closer to Quebec City.

3. Château-Richer Holdings (1646) Robert already held a substantial land grant of 6 arpents by 126 arpents at Château-Richer, granted in 1646.

But the couple didn't just accumulate property—they managed it strategically. And on September 12, 1655, they made a move that would demonstrate their sophisticated understanding of colonial economics.

The 500 Livre Transaction

On September 12, 1655, Robert Drouin and Marie Chapelier sold their Notre-Dame-des-Anges property to René Chevalier, a master mason, and his wife Jeanne Langlois for 500 livres tournois.

On September 12, 1655, Robert Drouin and Marie Chapelier sold their Notre-Dame-des-Anges property to René Chevalier for 500 livres tournois.

Most habitants earned between 100-200 livres per year. This single property sale was equivalent to two to five years of income for a typical family.

When René Chevalier resold the property in 1686 for only 350 livres—a loss of 150 livres over thirty years—it became clear: Marie and Robert had sold at the peak of the market.

The Bottom Line

This wasn't subsistence farming. This was entrepreneurial property management.

Building the Next Generation

Between 1650 and 1664, Marie gave birth to eight children with Robert:

- Marie (1650-1664) — tragically drowned at age 14

- Nicolas (1652-1723) — would have 15 children

- Pierre (1653-c.1666) — died as a child

- Marguerite (1655-1692) — married Jean Gagnon, had 8 children

- Étienne (c.1656-1732) — would become his mother's ally; had 11 children

- Catherine (1660-?)

- Jean-Baptiste (1662-c.1681) — died around age 19

- Marie-Madeleine (1664-1665) — died at 2 months old

Despite losing four children, Marie successfully raised six to adulthood—a remarkable achievement in an era of high infant mortality.

The Widow's Challenge

June 2, 1685: Everything Changes

On June 2, 1685, Robert Drouin died at approximately 78 years old. Marie was now about 60 years old, with grown children and substantial property holdings.

Under French colonial law, as a widow she had full legal capacity to manage property, enter contracts, and represent herself in court. Unlike married women, widows were legally autonomous.

Marie would need every bit of that autonomy.

The Donation Mystery

At some point before 1685, Geneviève Drouin and her husband Romain Trépagny had made a donation to Robert Drouin and Marie Chapelier.

Whatever the donation was, one thing became clear after Robert's death: Geneviève and Romain wanted it back.

Marriage Donation of Romain de Trépagny and Geneviève Drouin — Beaupré, New France — January 17, 1694

Under French law, donations were irrevocable. Once given, they could not be recovered simply due to changed circumstances or donor's regret. But Geneviève and Romain apparently believed they had grounds to challenge the donation's validity.

By 1693, the dispute had escalated to legal action.

The Four-Year Legal Battle

Level 1: The Bailiff of Beaupré (April 27, 1693)

The first battlefield was the court of the bailiff of Beaupré. Geneviève and Romain filed suit seeking to void the donation.

The bailiff heard the evidence: The donation was valid and irrevocable. The claim was denied.

Level 2: The Provost Court of Quebec (January 16, 1694)

On January 16, 1694, the court considered the appeal: The bailiff's decision was CONFIRMED.

Level 3: The Sovereign Council — First Round (1695)

The Sovereign Council was the supreme judicial body in New France, answering only to the King of France.

July 11, 1695: The First Major Victory

"Appeal of Romain Trépagny and Geneviève Drouin... SET ASIDE (mis à néant); the said Trépagny and Drouin being CONDEMNED to the sum of 60 sols fine."

The phrase "mis à néant" means "made void." The Council declared the appeal had no merit whatsoever—and fined them for bringing a frivolous lawsuit.

August 22, 1695: Default

Trépagny failed to provide required documents. Default judgment for Marie.

Level 4: The Sovereign Council — Second Round (February 13, 1696)

The ruling was explicit: "Appeal... DISMISSED, costs compensated."

Level 5: The Final Appeal (December 4, 1696)

The Sovereign Council rendered its final judgment:

"Appeal dismissed by Étienne Drouin and Marie Chapelier... and the appellant ordered to pay costs."

Marie's son Étienne had joined as co-plaintiff. The family chose sides, and Étienne chose his mother.

December 4, 1696 — Final Victory

Final Score

Duration: Nearly 4 years (April 1693 - December 1696)

Courts involved: 5 different judicial levels

Costs paid by Trépagny: 60 sols fine + all court costs + 4 years of legal fees

Three Months Later

March 15, 1697: The Victor Dies

On March 15, 1697—just three months and eleven days after her final legal victory—Marie Chapelier died at the Hôtel-Dieu de Québec. She was approximately 71 or 72 years old.

Marie Chapelier died undefeated, having successfully defended her property rights through every level of the colonial judicial system. Her son Étienne inherited her tenacity and her legal vindication. The donation remained valid. Her legacy was secure.

Why She Won

Legal Principles

- Donations Are Irrevocable — Under French law, a donation could not be revoked simply because the donor regretted their generosity.

- Time Limits Matter — Decades had passed since the donation. By waiting so long to challenge it, Trépagny weakened his case.

- Documentary Evidence — The donation was properly documented. Marie had notarized records supporting her position.

- Widow's Rights — As a widow, Marie had full legal capacity to defend her property interests.

Strategic Advantages

- Literacy and Education — Marie could read and write, understanding her own rights.

- Church Support — The ecclesiastical official sided with Marie.

- Family Alliance — When Étienne joined as co-plaintiff, it showed family solidarity.

- Patience and Resources — Marie sustained a four-year battle. She never backed down.

Why This Matters

For Women's History

- She was not passive. Marie negotiated her own marriage contract, managed property, and defended her rights through the highest courts.

- She was not uneducated. Her literacy gave her power that most women lacked.

- She was not a victim. When challenged, she fought back—and won decisively.

For Genealogy

Marie Chapelier is the direct ancestor of thousands of French-Canadian descendants through her children Nicolas, Marguerite, Étienne, and Catherine.

The Legacy

Every person who descends from Marie Chapelier carries the DNA of a woman who refused to be defeated.

What We Can Learn

- Literacy is power. Her ability to read and write transformed her agency.

- Documentation protects rights. Proper notarization enabled her victories.

- Persistence pays. Four years, nine judgments—she never quit.

- Family alliances matter. When Étienne stood with his mother, it strengthened her position.

Marie Chapelier signed her name on November 26, 1649. Nearly fifty years later, that signature would prove prophetic: she was a woman who knew her worth, understood her rights, and would defend them to her last breath.

She was undefeated. She died victorious. And her story deserves to be remembered.EPILOGUE: THE DOCUMENTS

This story was reconstructed from primary source documents held in the Archives nationales du Québec, including:

Marriage contract (November 26, 1649) - Notary Guillaume Audouart

Land sale contract (September 12, 1655) - Sale for 500 livres

Land survey (September 11, 1675) - Surveyor Jean Guyon

Census records (1666, 1667, 1681)

Sovereign Council judgments (1695-1696) - Multiple documents

Parish registers - Baptisms, marriages, burials

PRDH database - Genealogical compilations

Each document was painstakingly located, transcribed, and analyzed to reconstruct this remarkable woman's life.

The handwritten Sovereign Council registers, with their elegant 17th-century French script, testify to a legal system that—while imperfect—provided justice even for a widow in her 70s against powerful family members.

Marie Chapelier signed her name on November 26, 1649. Nearly fifty years later, that signature would prove prophetic: she was a woman who knew her worth, understood her rights, and would defend them to her last breath.

She was undefeated. She died victorious. And her story deserves to be remembered.

About the Research

This blog post is based on extensive primary source research using documents from Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ), the Programme de recherche en démographie historique (PRDH), notarial records, Sovereign Council registers, census records, and parish registers from 1636-1697.

Special acknowledgment to the genealogical researchers and archivists who have preserved these documents for over 300 years.

Explore the Complete Case Study

View the full methodology, interactive timeline, family tree, and all 15 primary source documents.

View Complete Case StudyWant to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY